Memorie.al / The occupation of Albania by fascist Italy in April 1939 is known to have had a wide resonance in Albanian historiography. But it has often been abused, or rather, the “I”s have not been dotted, just like with other fragments of our history. In fact, it seems as if we have only ever dealt with two characters (of course, this doesn’t apply to professional historians), let’s say, respectively, the Italians and the Albanians, forgetting the historical context and the other actors who contributed to this dirty business, which in a way sank the fate of a small nation.

Thus, by digging through an article from the archives of the American magazine ‘TIME’ (original title: “Birth & Death”, Monday, April 17, 1939), published just ten days after the occupation of Albania by Mussolini’s troops, we learn a lot about the historical, political, and diplomatic background that paved the way for this occupation, which is marked in black letters in the history of Albania.

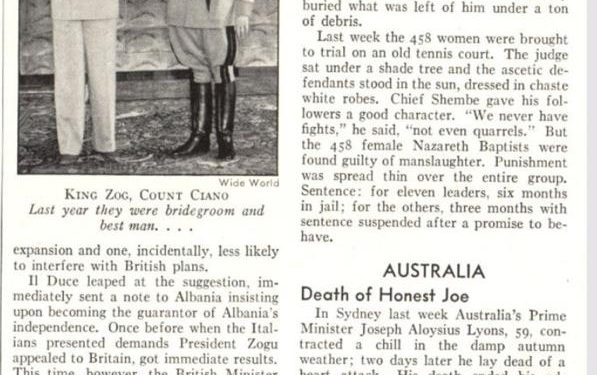

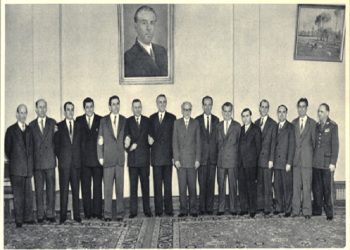

King Zog and Count Ciano, 1937

What stands out most in this article is the fact that for this step taken by Italy at the time, of course, besides its old declared and undeclared ambitions to have small Albania completely under its control, there is also the role, or rather the secret political games and the flirtation of British diplomacy with Mussolini, at the expense of Albania’s fate.

This fact is explicitly highlighted in the article, as it refers to the signing of the 1926 agreement, known as the Treaty of Tirana, which had previously received the “blessing” of the former British Foreign Secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain.

In addition, we have a clear and credible overview of the first days of the fascist occupation, the atmosphere in the Royal Court, the journey of the royal family and their escort, and the troubles and efforts to organize even a small resistance against the new occupier. At the end, the article emphasizes the importance that Albania had suddenly acquired, thanks to its geographical position, thus foresightedly anticipating the fate of its neighbors, while the Second World War was knocking at the door.

The article also has some, let’s say, inaccuracies, but in order to judge it better, we are publishing it in full and without cuts, inviting you to travel back in time and feel the atmosphere of those days, conveyed by a well-known magazine from a country across the ocean, which later, when the war was over, would become the number 1 superpower in the world, and would decide many things on our planet, but without being able to influence the fate of Albania. Let’s look concretely below at what the TIME magazine article suggests:

The article from the American magazine, ‘TIME’, about the events of April 1939

One morning last week, two hours before dawn, the sound of a shot broke the almost absolute rural silence of Tirana, the small capital nestled among the mountains, in the small Kingdom of Albania. Shot after shot and explosion after explosion, until they reached 101, shaking the sleepy city.

A boy and an heir had just been born to King Zog I, by his Hungarian-American wife, Queen Geraldine. The child was named Skander, after the great Albanian patriot, who in the 15th century, managed to keep the Turks at bay during about 30 years of fierce fighting.

Less than 50 miles away, in the Strait of Otranto, in the Italian ports of Brindisi and Bari, armed units had prepared for action, almost at the same hour. There, while warships, fighters, and other motorized military vehicles were prepared for the journey, people and heavy weapons were also getting ready to be transported. 384 fighter planes were at the airports.

48 hours later, the Queen, sick in her birthing bed, was staying in the temporary Royal Palace in Tirana, and could thus hear the sound of all the planes flying overhead one after the other, knowing well that they were not Albania’s, as her country had only two of them.

They were not dropping bombs, but leaflets that flew with the help of the spring breeze, warning the Albanian people that “friendly” Italian troops were arriving that day to take control of the small country, to “restore order, peace and justice.”

In the four Albanian ports, the closest one (Durrës), only 25 miles from Tirana, warships were soon seen, which began bombing. The troops had already landed. The war had begun. The small Albanian army, composed of 13,000 men, was quickly mobilized, and the brave mountain fighters brought out their old rifles, pistols, and axes from their homes.

But within a day, heavily armed fascist legions overcame this very small resistance and broke through the hills, reaching the capital. Within two days, they occupied all the important points of the country, with losses reaching only 21 dead and 97 wounded.

The Albanian army disappeared into the deserts of the Albanian Dinaric Alps, where the “Sons of the Eagles” (as Albanians call themselves) have hidden and fought until the Turks once came to an agreement with them. They are now expected to organize a guerrilla war until the Monarchy returns.

The Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, who was the most special friend and guest at Zog’s wedding last year, arrived there immediately to form a “provisional Albanian government” and the Duce, as much as he could, saved time from the meeting he had at “Palazzo Venezia,” to now announce in Tirana what he had just intended to do with his new “property.”

What can be guessed at best is that it can thus become a protectorate under the sovereignty of His Imperial Majesty, King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy.

Meanwhile, with the approach of danger, the 43-year-old King Zog I got into a car adapted as an ambulance, along with his 23-year-old wife and newborn son, whom he sent with a separate escort, on a journey of over 160 miles, on a rough mountain road towards neighboring Greece, staying in a small, primitive inn in Florina, near the border.

Her Majesty, through her Hungarian grandmother, Countess D’Estrelle D’Ekna, issued an appeal to the world with the words: “I left my husband leading his troops, the poor and small Albanian army — in war. What can Albania do against such a well-armed army as this, which is perfidiously attacking us?”

Meanwhile, King Zog moved the country’s capital to Elbasan, a city 25 miles southeast of Tirana. King Zog no longer continued to lead “his small army” in battle. Just one day after the Queen’s arrival, he joined her in Florina. With him went 115 members of his Royal Court and also ten heavy suitcases with valuable objects.

Going first to Thessaloniki and then to the coastal resort of Volos, the Albanian royal family was then notified that Greece, fearing for his shelter, could not offer them long-term asylum. As soon as the Queen’s health improved, they got ready to go to Egypt, a Muslim country that is very polite and warm towards distinguished visitors.

Also, a man who was expected to move a little later to a less turbulent country was the banker J. P. Morgan and his friend, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was thus quietly, received in Athens, on Morgan’s yacht, the Corsair.

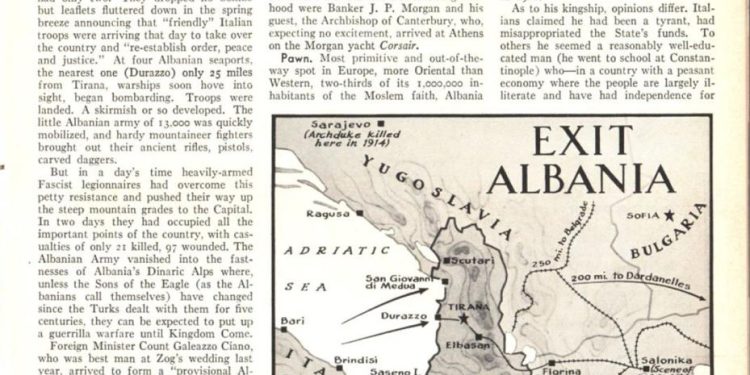

The most backward and primitive country in Europe, more oriental than western, two-thirds of whose 1,000,000 inhabitants are of the Muslim faith, Albania does not present much economic benefit for the Empire of the Roman dictator, Mussolini.

The main exports (almost entirely to Italy) are skins, cheese, and tobacco. Albanian oil is at best of second quality, and most likely capable of supplying even less than a tenth of Italy’s needs, even in peacetime. Moreover, in King Zog, the Duce has had to defeat a King, as any normal dictator would want.

A member of the Albanian Mat tribe, the son of a hereditary chief of the Mat Valley, Ahmet Zogu has inherited the typical characteristics of a Balkan politician, whose country must forever remain a hostage to power politics. He was once forced to leave the country. But he returned again, became President, and then took the crown in 1928.

Regarding his Kingdom, opinions are different. The Italians accuse him of being a tyrant and of abusing state funds. For others, he is seen as a well-educated man (he went to school in Constantinople), who in a country with a peasant economy, where people are massively illiterate and have only enjoyed independence for 27 years, has done the impossible to reform and develop it.

He has tried to put an end to the blood feud, one of the deeply ingrained traditions in that country. If Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain is now alarmed by Italy’s attack, he should not blame anyone in general, but his country and in particular his now deceased half-brother, Sir Austen.

In 1926, the Duce was putting pressure against Ethiopian “expanded interests.” To distract him from this issue, the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain, made it known that Albania was a more convenient market for Italian expansionist interests and which incidentally did not interfere at all with British strategic interests.

The Duce accepted this suggestion, and immediately sent a note to Albania, insisting that he thus became the “guarantor of Albania’s independence.” In a previous case, when the Italians presented their demands to President Zog, the latter appealed to Great Britain and received an immediate response from it.

At the time, however, the British Foreign Minister informed the President in Tirana that “London expected Albania to reach a friendly agreement with Italy, without unnecessary delays.” Sir Austen and the Duce then met on a yacht outside Livorno, to finalize the results of their agreement. The Treaty of Tirana, which made Albania a virtual Italian economic protectorate, was signed precisely on November 27, 1926.

That the consequences of post-war political agreements (First World War; translator’s note) tend to turn back and fall on one’s head, this was evident not only in what happened in Albania, but also in the fate of Ethiopia, three years earlier. Last week, Albania suddenly became important. Along the South of Albania, from Durrës towards Thessaloniki, lies an ancient road that once connected Rome with Byzantium (now Istanbul).

The Italian forces could advance again along this old imperial road, most recently used in the First World War (translator’s note), in the battle of Thessaloniki, now partly equipped with a railway, and thus could practically also cut off the road, from which the British and the French could send their aid for a threatened Yugoslavia. / Memorie.al

“TIME-Magazine”-USA 17.4.1939