From Brikena Bogdo

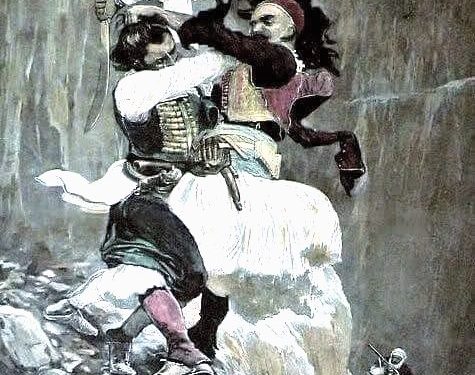

Memorie.al / Albanians know about the war for the defense of Hoti and Gruda in 1880, but they know very little about the figure who led this war. After Plava and Gucia, the entire resistance of the League of Prizren moved to Shkodra, where the central figure was Hodo Pasha Sokoli, of the same stature as Ali Pasha Gucia and Abdyl Frashëri. During the years 1920-1930, folk songs dedicated to the events of the League of Prizren were published, as well as to the leading figures, as a testimony to their resonance in popular consciousness. The distinguished leaders of the movement, Abdyl Frashëri, Ali Pash Gucia, and Hodo Pasha Sokoli, are also mentioned there. The people wove verses for these three central, leading figures of the League of Prizren. But unfortunately, the entire history and life of Hodo Pasha Sokoli, the fighter who led 10,000 soldiers in the war for the defense of Albanian territorial integrity, about whom the national poet Father Gjergj Fishta, in “The Highland Lute,” wrote: “Hodo Beg like thunder / The roar went to the King’s tent…”, was distorted by the communist regime before the ’90s?!

“Hodo Pasha Sokoli spent his entire fortune to maintain and lead an army of 10,000 fighters,” say his granddaughters, Fitret (90 years old) and Sabrije Sokoli, 88 years old, after 134 years. “The foreigners never managed to take the lands that Hodo Pasha Sokoli defended with the 10,000 fighters,” his granddaughters simply say.

Unfortunately, during the communist regime, the grandsons of this great house of the Sokolaj family (Ramadan Sokoli, Hodo Sokoli, and Ibrahim Sokoli) suffered in communist prisons, completely crucifying this legendary figure.

Consequently, the family’s history was distorted, and serious facts about the figure of Hodo Pasha Sokoli were twisted. The regime would penetrate the people’s verses to erase his name, the events, and his cardinal role in a war against the Great Powers and the High Porte for autonomy and even complete independence.

That figure remained a legend despite all attempts to erase the realities. A legendary family carved into legends, which shows how 25 men from this family left to fight against the Vizier of Turkey and only two returned, one of whom was Aftabegu, the legend of Shkodra, the ancestor of Hodo Pasha Sokoli. As soon as Aftabegu entered the bazaar of Shkodra, he addressed an elderly man: “It’s good to be here, good old man of Shkodra.”

He replied: “Welcome, Aftabeg of Shkodra.” Aftabegu, surprised, asked how he knew him, as he had been away for years, in wars. “By the weapon,” the elderly man replied. If the weapons of this family were almost a legend, its hearth is a tangible legend, even today.

His great-granddaughter Teuta (Haxhihyseni) Bogdo, recounts her childhood experience like a fairy tale. “In the house, the main room was dominated by the rare, masterfully carved hearth, while the large room was filled with silver weapons, among which the sword of Hodo Beg Sokoli stood majestically.”

The dictator Enver Hoxha had to undo the legend, had to undo the essence of this family, and had to annihilate its identification, the weapon. And the legend continues the story that during the communist period, Enver, among many diabolical ways to dismantle the family (by putting all the men of the family in prison), followed the one of minimizing the power of this family, specifically the weapon.

The “Achilles’ heel,” the family’s power, was the weapon, and it was precisely the sword of Hodo Pasha Sokoli that Enver gave to Stalin. He achieved two goals: he tried to undo a legend and gained an ally, showing him to be a loyal servant. The squanderer of his family, of the legends of his nation’s history, could certainly be the most faithful servant. The tribute was very high. By denying the essence, everything would be much easier to displace the figure, to distort history.

Hodo Sokoli, his grandson (named in honor of this figure), wore Hodo Pasha’s ring, of a rare value, which he never took off his finger. This ring was Hodo Pasha’s seal, with which he signed. When he was arrested by the communist regime, the State Security confiscated it, never to return it, finally erasing the identification of his personality as a leader.

If the fate of Hodo Pasha’s silver sword is known, the fate of this ring is not. But one fact is clarified: that Enver wanted to dismantle this heroic figure from its core, by destroying his weapon and ring (signature), which had national, historical, and undoubtedly monetary values.

Unrepeatable and irreplaceable figures after the Skanderbeg-ian era. These two legendary eras are connected by the same psyche: figures who know how to unite, to become invincible. It was these figures, after the era of Skanderbeg, who came together in a completely unequal war against the High Porte, the Great Powers, to repel them. Figures who knew how to unite forces, with the motto that unity makes strength. This makes them unrepeatable for the fate of the nation.

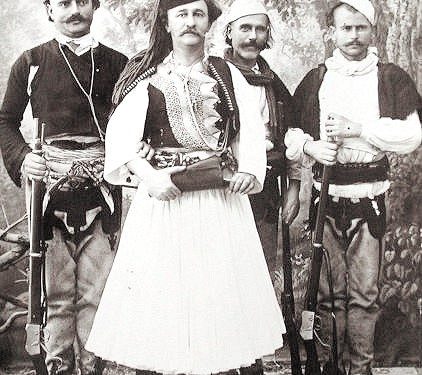

Hodo Sokoli was born on November 17, 1834. Over time, he managed to acquire a good education by attending the “Ruzhdije” school. A tall, handsome, and very authoritarian man, but above all, brave and known for high virtues. Stemming from a family with ancient traditions in Shkodra, he earned a deserved place of honor.

For his military talent, he was appointed captain of the guard of the lake islands, bordering Montenegro. He was a captain when Abdi Pasha Çekrezi was governor, in 1860. Later, he was promoted to major of the military gendarmerie, newly formed at that time.

On the occasion of Dervish Pasha’s arrival as Vali in Shkodra in 1869, he was transferred in the form of internment to Istanbul. An activist of the League of Prizren and chairman of the Albanian League, with its center in Shkodra. From April 19, 1880, he openly came out against the decision of the High Porte to hand over the regions of Hoti and Gruda to Montenegro, throwing to the ground the medals and honors he had won during his military career in the gendarmerie.

The fact that he exchanged his uniform for traditional Albanian clothes at the meeting further strengthens this symbolic act. Dom Pal Shantoja describes this day in detail in the form of an article. On April 19, 1880, the day after the signing in Istanbul of the “Protocol on the borders of Turkey and Montenegro,” one of the biggest demonstrations that city had ever seen took place in Shkodra.

On that day, in the square in front of the library building, at the foot of Rozafat, all the citizens gathered, along with thousands of villagers from the district. According to the letter that Engjëll Çoba wrote two days later, the rally discussed the decisions that the Inter-regional Committee had made regarding the defense of Hoti and Gruda.

He described the popular rally with sensational political announcements. His letter, written in the form of a report, addressed to the newspaper “Algemeine Zeitung,” was published on April 20, in one of its columns, and was republished in almost all European newspapers. What left a deep impression on European opinion was a warning phrase: “If the Great Powers have given up the principles of justice, the Albanians will shed their blood for sacred freedom.”

The popular rally took place under the leadership of Hodo Bey Sokoli, where it was made clear that the Albanians are determined to defend Hoti and Gruda to the end. According to Dom Pal Shantoja’s letter, at the rally in Shkodra on April 19, 1880, Hodo Sokoli, the chairman of the Military Staff of the Albanian League for the vilayet of Shkodra, gave a fiery speech.

He said, among other things: “Honored brothers of the Albanian League! The ministers of the Great Powers who gathered in Berlin acted with complete ignorance of our country and its inhabitants when they sold us, who are the purest and most noble race in the world.

But we, the great-grandsons of Skanderbeg and his fellow fighters, abandoned by everyone and surrounded by a pack of hungry wolves, waiting for prey, we will know how to defend ourselves and honor the graves of our fathers. We suppressed our sorrow and trampled on our most sacred feelings when our brothers in Podgorica and Shpuza were handed over to the enemy. We, even now, do not want to change the state of things by force.

For us, this was the last concession we could make, but tomorrow, our brothers of Hoti, Kastrati, and Kelmend will again be given to the enemy. Will you allow this?” A powerful “No” – the letter of Pal Shantoja continues, which came from thousands and thousands of chests, the immediate answer was given to Hodo Sokoli.

Then the orator continued: “I, too, do not want to allow this concession. Today, having learned the evil spirit of the Sultan and his clear will to sell us as slaves and destroy us as a race, from this moment, I am breaking away from him and I have no intention of recognizing either the Padishah or Istanbul.

Immediately after pronouncing these words – the mentioned letter further says, the brave old man tore the golden epaulets from his military uniform, tore the many decorations from his chest, threw them on the ground, and trampled on them. His example was followed by 150 officers who were present at the meeting. Then Hodo Bey shouted: “O men! Let’s show the world who we are and what we really want. O flag-bearer of Hoti, now fulfill your duty!”

Immediately, Ismail Marku, the flag-bearer of Helmi (Hoti), a big man with a sun-tanned face, came out on the balcony of the building and, with one thrust of his yatagan, broke the spear where the crescent flag was waving. The Sultan’s flag fell to the ground, into the dust. Then, the flag-bearer of Hoti, Çun Mula, amidst uncontained cheers, waved the national red flag.”

However, who actually raised the red and black flag that day is highly debatable. There are versions that say Hodo Sokoli himself raised the flag. According to Shantoja’s letter, Hodo Sokoli took the floor again. He eloquently explained the state of affairs and presented the mindset for winning the war that would be undertaken against Montenegro.

“We have weapons, in fact, we have plenty, and we do not lack ammunition, in fact, enough to fight for several years, only money is what we lack, as Albanians are brave but poor.” At that moment, the chairman of the guild of coppersmiths gave on the spot, as help, to cover the needs of the fighters who were under arms, 500 gold pounds, and promised to give more soon. Nevertheless, Pal Shantoja’s letter had a profound echo in European public opinion.

Its sensational aspect lies in the fact that, in addition to a war being expected between Albanians and Montenegrins, a separation of the Albanians from centuries-old Ottoman rule was also being announced. This scent of gunpowder prompted some European press organs to send their special correspondents to closely follow the shocking Albanian events.

But the figure of Hodo Pasha had begun to be discussed in diplomatic circles even before April 19. Regarding this, Kirby Green, the English consul in Shkodra, wrote to the Marquis of Salisbury, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Great Britain: “You’re Grace, the unrest here regarding the foreseen cession of some Catholic highlands to Montenegro, in exchange for Gucia, still continues, but it is quite difficult to understand how it will end.

Some people who play a leading role in them have assured me that it is intended to overthrow Izet Pasha, the governor-general, and to appoint Hodo Bey, the head of the police and the head of one of the most influential Muslim families in this city, in his place.” (Shkodra, March 29, 1880).

But Albania turned out to be alone. The attention of the population of Shkodra was once again directed towards the border, for another reason, this time provoked by the Great Powers. With their consent, England sought to force the High Porte to establish a military cordon in the Hoti and Gruda area to prevent volunteers from going to the Tuzi area.

The government of Istanbul tried in every way to avoid confrontation with the Albanian population. To the question of the British ambassador, Lord Goshen, as to what prevented the Porte from establishing the military cordon; Savas Pasha replied with the words of the vali of Shkodra that if it were established in the Tuzi sector, the Albanians had threatened to attack Montenegro to retake Podgorica.

Furthermore, to Goshen’s other question as to how the fact that a golden official like Hodo Sokoli had become the leader of the rebels could be explained, Savas Pasha replied: “He was an Albanian and as such, he had entered the committee of the League of Shkodra, without the consent and authorization of the Ottoman government, consequently, he had lost his official functions.”

J. Haxhivasiljeviçi calls the momentum that the autonomist movement in Shkodra gained a “national revolution.” He sees its beginning in the rally of April 19, when Hodo Sokoli removed his epaulets and titles and was joined by many other functionaries, and also raised the Albanian flag, an event which he calls a coup d’état. According to him, the rays of this revolution also spread to Kosovo. Here the coup d’état occurred in Prizren on May 12, 1880. On that day, the Kosovars expelled the mutasarrif of the High Porte, Ahmet Spahiu, from Prizren.

The growth of the autonomist movement in all four corners of the country was also reflected in the pages of the international press. Some thought that Albania would now gain autonomy, and would even rise, as the newspaper “I foni tis Alvanias” wrote on May 24, 1880, to the level of an independent principality.

(Hodo Bey Sokoli, commander of the gendarmerie of the vilayet of Shkodra, a prominent activist of the Albanian League of Prizren, commander of the Army of the Albanian League of Prizren, in defense of Hoti and Gruda, against the forces of the Montenegrin army). Memorie.al

*The material is an excerpt from the review, prepared by Brikena Bogdo, held at the symposium organized by the association “Trojet e Arbrit,” August 2014.