By Uran Kalakulla

Part forty-one

Nazism and communism

Memorie.al / Nazism lasted 12 years, while Stalinism lasted twice as long. In addition to many common characteristics, there are many differences between them. The hypocrisy and demagogy of Stalinism was of a more subtle nature, which was not based on a program that was openly barbaric, like Hitler’s, but on a socialist, progressive, scientific and popular ideology, in the eyes of the workers; an ideology that was like a convenient and comfortable curtain to lie to the working class, to lull the sharpness of intellectuals and rivals in the struggle for power.

One of the consequences of this peculiarity of Stalinism is that the entire Soviet people, its best, capable, hardworking and honest representatives, suffered the most terrible blow. At least 10-15 million Soviets lost their lives in the torture chambers of the KGB, martyred or executed, as well as in the gulag camps and others like them, camps where it was forbidden to correspond (in fact, they were prototypes of the Nazi death camps); in the mines in the ice of Norilsk and Vorkuta, where people died from cold, from hunger, from crushing work in countless construction sites, in the exploitation of forests, in the opening of canals and during transportation in leaded wagons, or in the flooded barns of the death ships.

Continued from the previous issue

We parted ways with Dom Ndoc when I was released and left him in prison. But unlike many other old men, with whom I was not lucky enough to meet again, now outside the prison, without looking…! I met Dom Ndoc again, in the corner of a Shkodra flower garden, quite by chance. We hugged each other with longing and love and he told me to be careful, because; “the communists are very vile, they will put you back in prison, without doing anything wrong”! And indeed, I was exiled shortly after, with my whole family, for five years, and I did not see that good old man again.

The writer of socialist realism and the Marxist “doctrinaire”.

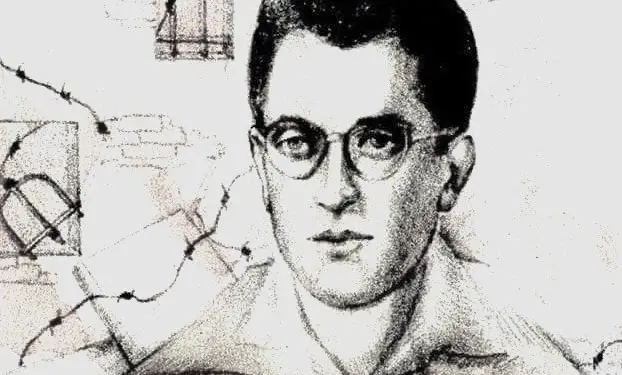

In one of the rooms of the Burrel prison, in “wing 1”, where I had been transferred, among others, I also met two interesting characters, both intellectuals, types characteristic of me, whose history and portrait I think are worth presenting to the reader. The first was a well-known writer in the line of Albanian socialist realism authors, author of several novels or memoirs, which came out of the press immediately after the communists, came to power. This was Kin Dushi.

Kin Dushi was a man of average height who, although he had been in prison for years, still seemed to be somewhat healthy, although poor, he had no help from outside the prison and was severely tormented by hunger, apart from other needs for clothing, cigarettes, etc. He was a man of good character, not arrogant, with a great deal of experience in life, having experienced good, prosperity, and evil, poverty, he had experienced both position and the upside-down fall from it. Exactly as it happened during the communist rule of Enver Hoxha in our country, and finally, as it happened throughout the so-called “Socialist Camp” of Stalin.

Orphaned at a young age, he was raised in the “Streh Vorfnore”, experiencing all the deprivations, the discipline of cloistered life, the arrogance, the insults and even the beatings of cruel guardians, more or less as shown in a film, which if I am not mistaken, is entitled “Lulëqet mbi mure” by the Kinostudio “Shqipëria e Re”, I do not know which year, the production of “Streh Vorfnore”, in dormitories, to finish high school. Being from Shkodra, it seems to me that he was (if I am not mistaken), a student at the Shkodra high school and a boarder at the “Malet tona” dormitory of that city, a dormitory where the communist ideas of the Shkodra Communist Group had taken root, with Zef Mala at its head, a story that is now quite well known.

Thus, Kini was also listed, during the war, in the partisan ranks, reaching the position of political commissar of a partisan battalion. But in the meantime, I don’t know how it happened that he had fallen into the hands of the Germans and they had imprisoned him, like many other communist activists, or those close to them, in the Pristina Concentration Camp. This infamous camp was like a “prelude” to the Nazi camps in Germany, Austria, etc., extermination camps, as is known worldwide. But Kini was lucky to get out of that camp alive. It is understood that Kini was well received by his friends who were already in power, and he began working as a journalist, while also engaging in literary creativity, like his colleague, even more famous, veteran of the Spanish War, Petro Marko.

Thus, the first literary fruit of this second activity of his is the book of memoirs, with the significant and apt title “In the Wolf’s Mouth”, which was quite well received at the time, where he talks about the suffering and dangers of himself and his friends in the infamous Pristina Camp. He then continued with his literary creations. I do not know all of his publications in this direction, except for two novels: “The Way of Velekolamit” (What is this name?) and the other and last novel, entitled “A Name among the Stars”. Of course, it is neither the place nor the occasion to deal here with my critical assessment of these novels, especially since I have not read the last one at all.

I have only read from Kin; “In the Wolf’s Mouth” and “The Way of Velekolamit”. In fact, I had read this “The Way…” carefully, and to be honest, I did not like it at all. It was something similar to Kolë Jakova’s play entitled “Our Land”, which was highly regarded at the time, as is known, and even highly valued, because it responded to the party’s line, in its efforts to invent the “socialist village”, turning the poor peasants into medieval serfs, if not worse.

Of precisely this nature was Kini’s novel “The Way of…”, about the war against the kulaks (a name imported from the Soviet Union), who were nothing more than capable farmers, who knew how to work, within the framework of the time, and manage their well-being with the sweat of their brow, owners of their land inherited from generation to generation, or purchased with cash, with regular official documents, but who had one single problem: they did not want to put their necks under the yoke of the socialist cooperative.

This was also the reason why they were declared class enemies and the object of countless persecutions by the “beloved popular power of the workers and peasants”. Oh, what a popular power that was!

As a journalist at “Zërin e Popullit”, Kin heard about a trial held in Lushnje, against a group of kulaks who had badly sabotaged the peasants’ attempt to establish their beloved agricultural cooperative. It seems that Kin rushed to that trial from Tirana, took copious notes and when the “hostile group” received the “deserved decision” from the “people’s court”, he wrote with great zeal the novel “Udha e …”, a voluminous novel, but which did not have the fame, as far as I remember, nor the appreciation of “Toka jone” by Kolë Jakova. However, as I said, I read it carefully.

The protagonist of that novel was a rich, muscular peasant, with a long mustache from ear to ear, reminiscent of the type of saboteurs, as presented in the Albanian socialist film, wild and cunning, in a word “the devil of hell”, as they say in Shkodra. But this corpulent mustache, in the investigator’s eyes, had apparently “taken off his pants” and had accepted the entire scenario of the State Security recorder, and had even agreed, in order to “expiate his guilt”, to become an accomplice of his convicts, in the prison where they had shaved him. Now let’s see how the writer Kin Dushi happened to meet the protagonist of his novel.

When the P.P.Sh. broke with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (meaning Enver with Khrushchev), and the fight against revisionism gained momentum, Kin’s third and last novel, “A Name Among the Stars”, was called revisionist in spirit, was banned from circulation, after planned criticism by the party, and after a short time its author, the writer Kin Dushi, was arrested and convicted as an “enemy of the people”, as; “follower of the revisionist line in literature” and other such things. He was sentenced to eight years in prison and had to serve his sentence in Burrel prison.

But to Kin’s surprise, the protagonist of the novel “The Road…” was right there in that prison, not like Kin in line, like sardines in the convicts’ vats, but in the prison infirmary, with a special bed, with special food (the worker’s), while the communist Kin, ate like the rest of us, the langur of the cauldron and 600 gr. of bread! Having established a confidence, I would tease the writer Kin, telling him that it would have been better to be the protagonist of his novel, than a writer himself. And Kin laughed, and although his laughter had a pronounced note, both sadness and malaise.

Although in prison, and even in Burrel, Kin kept his character unblemished and towards the command cadre he was firm, serious, dignified. I have never seen him faint, cry, or beg for anything from any policeman or officer, even the prison commander. Even in his extreme poverty, despite the great hunger that tormented him, I never saw him extend his hand to anyone to ask for food. He politely accepted only what his fellow prisoners gave him, when his heart told him to. And he thanked them nobly.

And he got along very well with his fellow prisoners. He was not a stingy man, much less arrogant. The heavy blows of life, from childhood to old age, had already taught him that this life in general, and Albanian life in particular, does not really accept arrogance or being held in high esteem, whether intellectual or writer. On the contrary, Kini best confirmed my eternal philosophy in this regard, a philosophy which, in essence, says that; “the more knowledgeable a man is, the higher he climbs in the hierarchy of social life, the simpler he must be, the more sociable and knowledgeable, especially with the simplest people of the people, with a modesty that is true and not feigned, hypocritical”. And all this because, a true, knowledgeable intellectual, the more he needs to learn from simple people, from the great wisdom of the people.

Kini had a formed, stable character. He did not turn his back on the wind. Communist ideas had entered his blood, since his adolescence, as we have said. Thus he continued to call himself a communist, but an “ideal” communist for an “ideal communism”, it seems, is simply theoretical, that I do not know at what point on the globe it was realized, or could ever be realized. Thus, without realizing it, he had fallen into the positions of a completely abstract utopianism and, so as not to confuse him with the well-known pre-Marxist utopians and, somewhat close to him in time, I would say with Campanella’s “Sun City”. However, this was, I would call it, a weakness of his, which it was useless to erase from his mind. And I and the others left him to his own conviction and our topics of conversation usually did not touch at all, out of delicacy, the topic of his particular, communist ideology.

The bitter irony of fate also belongs to another of my fellow sufferers of the Burrel prison. His name was Gjergji Mole, originally from Korça, but naturalized as a citizen of the capital. His father had also served a long sentence, in that same prison. He had been a prominent intellectual, fluent in several European languages, a patriot who had abandoned Switzerland and returned to Albania to work for his homeland. Unfortunately, I don’t remember his name. He had left Gjergji Kalama and had lived with his son for a short time after he had been released from prison. But Gjergji had inherited from his father honesty and patriotic feelings and a discreet ability for foreign languages and culture in general, especially humanitarian ones.

But, surprisingly, although he was a big man, with considerable physical form and resistance, he was not very distinguished for bravery, apparently because he had been “beaten like a puppy”, as the people say, by persecution, as his father’s son. He had known how to survive, trying to avoid as much as he could, the great atrocities of the regime. And after he had completed high school, he had been able, like many others, taking advantage of the conjuncture of the time, to pursue higher studies at night by correspondence at the University of Tirana and had graduated in the history department.

He had not been brought to Burrel for punishment, like most of us, but as a painter, to do some work, where I know, on tables and graphs that the command needed. So he was a worker, who received 800 gr. of bread, a dish of meat (as much as this was), and a quantity of lek. Usually that who worked in prison, as in the prison camp’s rear, was, for the rest of us, suspicious people, or proven to be bad, in short, spies. But this should not be made absolute, because it is known that every rule has its exceptions. For example, the barber in Burrel prison, who cut and shaved us, convicts, for a period of time, was a boy from Narta in Vlora. They called him Kozma Todi. But Kozma was an example of virtue and honesty, loved and respected by all his fellow sufferers and, unlike that “kulak” scumbag, the infirmary cleaner.

Without a doubt, Gjergi Molja was also like that. Painter? No, sir, Gjergi was a kind of sketch artist who made posters and wrote slogans. Every enterprise had one of these, as a rule. The command of our prison also wanted one, and for this reason, the ministry (more precisely, the Directorate of Prisons-Camps) had brought Gjergji from Spaç to Burrel. As a person, Gjergji was a good man, gentle, kind and loving to his fellow sufferers. He was even generous and generous. I found him in the room where they took me, eating bread with Kin Dushi and helping him as much as he could, because they were like friends, respected each other and got along very well with each other.

They even teased each other without harm, because they both really liked humor, which, in prison, is, to a considerable extent, the health of the soul. Without it, life in prison would become ten times harder, gloomier. I have often thought and said that humor in prison, that is, laughter at evil, shows on the one hand purity of the soul and on the other hand, strength and stability of character. Humor in prison is like a challenge to the evil that has found you. Let him say the opposite, if he wants whoever he wants! This is my conviction, proven and in concrete fact, throughout all the long years of my imprisonment and that of many, many others. That one does not go through life only with a gloomy face, a heavy soul, languishing and cursing, not only outside the prison bars, but also inside them.

Thus, Gjergji with Kini often became the initiators of the explosion of collective laughter among all the members of the room. Kini’s true stories, especially as an authentic Shkodran that he was, had in a large dose that hint of the great humor of that city that is, as is known, one of its first characteristics, making all of Albania laugh, even beyond its state borders, wherever there are Albanians. But, taking this fact as a starting point, although Gjergji had nothing to do with Shkodra, he constituted for me on the one hand a separate object of humor, because he was characterized by a contradiction and a great paradox at that time, a defect which I believe he has already corrected where he has been living for years now, in the Italian canton of Switzerland. Even returning to his paradox, I would say that Gjergji’s strangeness had two quirks, both strange and funny, that could make you laugh out loud. And on the other hand, you could burst out laughing. Hey taxi drivers, what don’t you find in a person, what doesn’t life have!

The first paradox has to do with the worship of Marxism, which was considered at that time; “the science of sciences”, the only substrate of any kind of knowledge, whether humanitarian or natural, and even of any kind of art, or even ethics. Almost even mathematics had its roots in Marxism! Thus the young correspondence or night student, Gjergj Mole, the son of the “enemy of the people”, was so strongly taken by the love of Marxism, that he considered himself such a former Marxist that he could even give his own contribution in this direction, an original thesis of his own, approaching comrades Lenin and Stalin and, what seems even more interesting and important, surpassing even the “great comrade” Enver himself!

Thus Gjergj, after receiving his diploma, drafted a theoretical thesis of Marxism, stating and arguing that; “in a socialist society, one could start from feudalism, without going through capitalism at all”. Poor Gjergj, because he was kind-hearted, felt sorry for the people, who had to go all that long way and in several stages, because they were getting tired and wasting time in vain, in order to go faster to socialism, to the greatest happiness of humanity, to the earthly paradise! And the wonder does not end there, because with this thesis prepared, and, starting with the Central Committee of the Albanian People’s Party, I don’t know in which directorate there, they accepted his “scientific work”.

The “honorable” comrades of the Central Committee, welcomed him with a smile and clapped their hands, and since at that time there was no kind of “Academy of Marxist-Leninist Studies” in our country, they thought of sending Gjergj to China, to “test” him and to give him the degree of “doctor in Marxism”. Thus, the son of the “enemy of the people” would become a “doctor of science” (meaning something very learned), and perhaps even a Doctor Professor! Thus, the “great heart” of the “mother party” was wide open to welcome the prodigal son into her bosom.

I say that if the father had been alive, he would have taken his son with a wooden stick in front. But the suffering old man had died, the poor one, as a “reactionary” and his son was becoming a “revolutionary”, and even higher than that, he would become a great theorist of the Proletarian Revolution! Meanwhile, Gjergji continued to paint in the enterprise where he earned a living for himself and his family and counted the days, like a priest, impatiently waiting to be called “up there”, to be notified, to be given his passport in his hand, a handful of dollars and other papers, along with a plane ticket, towards the Pacific Ocean, always from the “Red East”.

Poor Gjergji waited and waited and, finally, the day came, only instead of a plane, a truck full of policemen, with their chief at the helm, showed up at the door of the apartment. In the loaded trucks, straight to internment, together with his family, in I don’t know which part of the Lushnja district. It seems that the Central Committee, in order to please Gjergji, had rushed to set up the “academy” very close by, so that the scientific candidate would not tire on the long journey, but right in the heart of Myzeqe. Thus ended the Marxist-Leninist dream of Gjergj Mole, one of my fellow sufferers in Burrel prison. Come on, there is more, as we will see below.

The path from internment to prison was very easy, just like from Spaç to Burrel prison. And now, we were “goats and sheep together”. And we would go out for air with Gjergj and start the theoretical conversation encouraged by him, avoiding as much as we could any unwanted ears. / Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)