By Uran Kalakulla

Part thirty-two

Nazism and communism

Memorie.al / Nazism lasted 12 years, while Stalinism lasted twice as long. In addition to many common characteristics, there are many differences between them. The hypocrisy and demagogy of Stalinism was of a more subtle nature, which was not based on a program that was openly barbaric, like Hitler’s, but on a socialist, progressive, scientific and popular ideology, in the eyes of the workers; an ideology that was like a convenient and comfortable curtain to lie to the working class, to lull the sharpness of intellectuals and rivals in the struggle for power.

One of the consequences of this peculiarity of Stalinism is that the entire Soviet people, its best, capable, hardworking and honest representatives, suffered the most terrible blow. At least 10-15 million Soviets lost their lives in the torture chambers of the KGB, martyred or executed, as well as in the gulag camps and others like them, camps where it was forbidden to correspond (in fact, they were prototypes of the Nazi death camps); in the mines in the ice of Norilsk and Vorkuta, where people died from cold, from hunger, from crushing labor in countless construction sites, in the exploitation of forests, in the opening of canals and during transportation in leaded wagons, or in the flooded barns of the death ships.

Continued from the previous issue

That’s all I said and I left the way I had come. It had already become clear to me: I was the first on the mark from the command. Therefore, I decided to be twice as careful as before. But I noticed that some other prisoners, cowards and servile, thank God, did not seem to approach me. It was clear that they were afraid of being compromised. The dominant psychology of the life of citizens outside the prison bars, the psychology of a great, monstrous fear, had begun to slowly enter the prison and prison camp. And I already knew this clearly. That is why I was not very pleased with the handshakes from friends and comrades, who did with me the same thing they had done with Bardhyl Belishova. Their solidarity alone was enough for me, which I recognized in their sincere and meaningful greetings and smiles.

To be honest, I had expected a ruckus of this nature as soon as I learned that the head of the Elbasan Branch, who (of course) also had the supervision of our prison camp under his jurisdiction, had arrived, the “black general”, Nevzat Haznedari. It is known that he had been accustomed for decades to find, as the people of Shkodra say, “the hair on the head”, that is, the hair on the head. That he was never satisfied with causing victims, as many victims as possible, to serve in the huge and terrible pit, like that of the mythological Minos, the dictator and his master. But it had not occurred to me that, among those victims, I was also thought to be, who, as I said above, usually showed myself to be very prudent and careful in such risky jobs, without concrete positive results.

But one day that month, on April 19, 1968, in the morning, like the other time, the whistles rang again. This time we would not gather in a crowd in the yard, but would be locked in the silos. The outer door opened and the operative with two captains entered, accompanied by the head of the technical office, the chief spy, the thief and the pedophile, Mehdi Noku. And together, they headed for the silo near the kitchen, where I was staying. As soon as they entered, they stood under my bed, on the door, and called me to come down with my clothes. I came down.

They put German handcuffs on my hands and told me to go forward through the door. – “What about the clothes, the mattress and the clothes, in the warehouse?” – I asked the operative. Instead, Mehdi Noku answered, seeming very pleased to be serving in such a job. Perhaps he was getting rid of an undesirable person, although with that garbage, I had neither come close to him nor had I ever caused him any trouble.

At the door of the courtyard, where a kind of curtain had been placed, covered with tar paper, so as not to see outside the large door made of barbed wire and with a guard tower, there was a small space. There they stopped me and began to search my buttocks. I believe not for a knife, because they knew that I did not carry one, but certainly for some letter, through which I would connect “my Party” with those of Burrel. Because it was already clear to me that that was where they would take me. I didn’t complain about my troubles at all, I was used to transfers by now, but when they happened, my mind was only on my family, especially my young wife, my little son and my old mother, who would take a long, difficult and dangerous journey to meet me where they would pick me up like a brand-new dengue fever.

Behind me, that first stop was filled with about five young men: Brahim Buzi, Agron Kalaja, Bajram Dervishi, Hekuran Shyti and Ramadan Lipe. I knew them only by sight and had almost never spoken to them, apart from being escorted and seated. They were simple, hardworking, uneducated boys, put in prison only for an escape attempt. I had heard about them that they were honest people. But could these have been members of the leadership of my Social Democratic Party?! I watched them carefully as they searched them too (more for knives, I believe, than for papers), and I almost laughed. What was this job?

Had they formed a group to break out of the camp, to escape? Maybe! Or to cause trouble and fights in the camp, as troublemakers? They packed us into the motor prison, but thankfully they took off our handcuffs. It could have been an inventory job for them. Who knows?! And we set off. Although we were locked up like in a cage, with no windows anywhere, with only a hole in the ceiling, just enough to get a little breath, we realized that the car was headed for Tirana, from Qafa e Kërrabës.

In Tirana, they stopped us at the new prison, where they also took five other young men who had come from prison camp 309 in Vlora: Qamil Hajdini (a boy from Tropoja, as tall as a telephone pole), Xhaferr Xhomo (a former zoo veterinarian) and three others, whose names I can’t remember now. So, in that motor prison, there were ten of us, with all our clothes, mattresses, quilts, blankets, curtains, cooking utensils and cups, gourds, bags of food and clothing, and me and a bag full of books and notebooks, some written and some unwritten.

Even if that damned vehicle had been an open truck, we would have been exhausted, not with a closed vehicle, a little bigger than a car, doing that whole route: from Elbasan to Tirana to the door of Burrel prison, in this damned place.

As far as I remember, two or three people pulled out their intestines and then we were forced to take in the smell of their vomit, along with other smells, which mixed with the heavy smell of badly burned fuel from that sloppy car. So, what were we to do? Where were we to go? We didn’t even have the opportunity to stretch our legs anywhere to rest them from all that long journey.

Finally, we arrived. The door opened and we began to descend with difficulty, with numb legs, bodies, and arms. And only when we had unloaded our bags where we told to line up in a semicircle, in front of the heavy iron door of the prison. We looked around and looked around, to understand where we were. In front of us, among the prison guards, a civilian was moving here and there, with eyes like those of a hyena, who was trying to investigate us with his sly gaze, while an evil smile was outlined at the corner of his lips.

Of course, he was pleased that he had a new desire to crawl into the dungeons and to take pleasure in torturing him. What a green face, cynical and sadistic at the same time! And he was a short man, so that the caparison, which he showed to the public, caused more than fear: a real disgust. And this is the operative of the Burrel prison, I don’t know what rank, but by the name of Shaban Hadri, from Kolonja. In my opinion, all pigs, as a popular Albanian proverb says, have a mug.

After he waved for a while in a demonstrative manner, like a butcher who buys a herd of cattle to slaughter and gets excited while interrogating them, Shaba began to make a kind of appeal, pointing to each one, to identify the faces with the names he had on the list:

– “What do they call you?” – he started from the beginning of the line.

– “Xhaferr Xhomo”! – The person being called had to stand up to identify himself better, as well as out of respect for the new gentleman.

– “What about you?”

– Kozma Todi!

– “What about you?”

– “Ibrahim Buzi”!

But the appeal did not continue any further. He looked around at all of us once and then suddenly asked:

– “Who is here, Uranus Kalakulla”?

I happened to be on the other side of that row. And, of course, like everyone else, I also stood up.

– “Oh, you were Uranus”?! – his lordship said ironically. And he continued:

– “Where are you, Uranus, because we have been waiting for you for a long time”?!

“Oh, you son of a bitch,” I said to myself, “you have been waiting for me, haven’t you?” And I thought who knows what he had written in those letters that had accompanied me and that perhaps had fallen into his hands before I got there. And I answered him with a voice and, since thought is much faster than words, I had time to talk to myself and give him the answer, not only in time, but also as it should have been: “I don’t know who you are, sir, but I’m telling you, I hadn’t made any request to come here”!

– “Do you know that we also have Pjetr here”! – he replied. Of course, I knew that he and another group had been brought to that prison from Elbasan1 for six months, as my job. So, I simply answered:

– “I know”!

– “We made him prime minister”! – he spoke again with irony. Then the devils really jumped at me, because for me the title “Prime Minister” simply translated as “dungeon”. Of course, neither one nor the other suited me at all. So, I answered him bluntly:

– “Listen, sir, I don’t know your name! My name is Uran Kalakulla and not Pjetër Arbnori. And, from our side, we have a saying that says quite clearly that: every ram depends on its own feet”.

– “Here, you have a sword in my tongue, sir”! – he answered me confidently with that refined irony of his, where even the first threatening notes were clearly felt. But I, nervous as I was, did not ask and turned back to him, without giving him any time to speak further at that moment:

– “Well, I know that man was given a mouth by God, not only to eat like cattle, but also to speak like humanity”!

– “Okay, okay”, – he said in that ironic tone of his, but this time even more openly threatening. – “Here we are, we will talk”!

Out of anger, I still didn’t want to let him have the last word:

– “True, I am here, and I have nowhere to go, even if I wanted to”!

With that, my dialogue with Burrel’s operative ended, and then he ordered the guards to open the big door like a monster’s mouth and let us in. That’s how long it took the captors. They rushed in like madmen, almost at once, quoting us a slogan written on a corner of the high surrounding wall, written in the bad handwriting of a semi-illiterate person: “Here they call Burrel, whoever enters, never leaves”!

We, the newcomers, certainly knew what Burrel was, as every other political prisoner had heard. His bad reputation had even crossed the borders of Albania, all the way to America, and from time to time “Voice of America” or “Radio London” had mentioned this scoundrel name.

Apparently, proud of this dirty name, the guards were also shouting with a slanderous pleasure, urging us to enter as soon as possible that majestic and silent prison like a tomb, unlike all the other prisons we had seen. They rejoiced like the devils of hell, who have just taken possession of sinful souls, with the precise task of torturing them eternally.

And these devils in the uniform of the Ministry of Interior guards were: Asllan Uka, Nezir (I don’t remember his last name), Ali Kurti and so on, mainly villagers from the Mati district, transformed into executioners, to torment and torture innocent people, just for the dictator’s whim and, to make what life they still had on earth, a real hell or, to bring death closer to them as soon as possible, despite our young age.

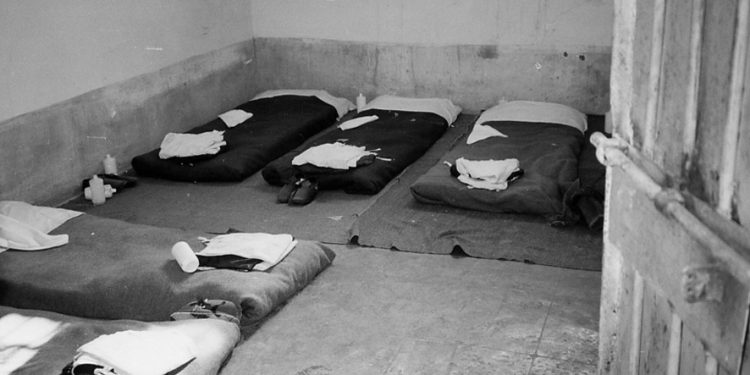

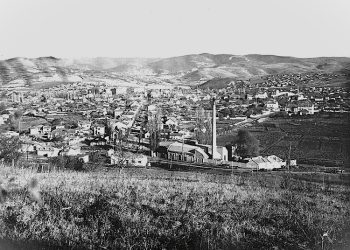

The gloomy shadow of Burreli prison

Every prison has a bad shadow. It is understandable why. But the shadow of Burreli prison had a special gloom, which smelled of death. Not for nothing, among the Albanian prisons of the Enver dictatorship, Burreli has been called the Dantesque “ninth circle of hell”. Of course, he had many “friends” of his, throughout the country, such as: Gjirokastra Castle Prison, the New Prison of Tirana, Shkodra Prison (better to say the prisons of Shkodra), and so on. But I don’t think I’m wrong when I say that Burreli’s had something special: the appearance of a monster.

And, this monster, always stands with its mouth open and, what enters its throat, does not come out alive, but only a corpse. And this was confirmed by the communists themselves when, at the beginning of the use of that prison, they had placed on its facade, after the name: “Prison of the enemies of the people”, a very cynical slogan, reminiscent of the one written at the entrance to Dante’s Inferno. Here, compare these slogans and you will see that they are quite similar, like two drops of water:

In Dante’s Inferno:

“Abandon all hope, oh you who enter”!

At the entrance to Burrel’s prison:

“Here they say Burrel, who enters, does not leave”!

Dantesque poetry?

Does the security guard have any reminiscences?! Although I know a lot about the terrible prisons in the history of mankind, I do not believe that such ghastly slogans were written in any of them! Judge for yourself now the sadistic spirit of the communist security! Well, the place where it was built, there was absolutely no gloom around and district. There was even a market around it, like the city that it was. But, when that building was officially designated as a prison, it seems that the entire surrounding environment took on a gloomy and frightening shade, something like the castle of Dracula. so well-known through American cinema, like the prison of the basements of the Roman Colosseum, of the victims of the first Christians, as history proves. Even an ordinary brick, if used by a criminal to break the head and open the brains of an innocent victim, when it comes out in court as a crime weapon, is seen by people with both fear and resentment.

And the communist security forces had a special ability: every object, when they touched it with their hands, they blackened it, turned it into something gloomy, frightening, hateful, an instrument of suffering, torture, and death of people. Why, didn’t they turn the shrines of God in Shkodra and some houses of honest and respected families of that city into prisons? Likewise, in some other cities of our unfortunate country. So, as for an unwritten law of human history, even a divine shrine, in the hands of any dictatorship, when used for its crimes, takes on a bad shadow, because it is identified with the dictatorship. The gulags of Serbia, the Ljubjanka of Moscow, Hitler’s Auschwitz and so on, endlessly, from peaceful places, in the hands of Dzerzhinsky and Himmler, received the curse of the people and the stigma of the shame of history. This is exactly what happened with Burrel prison and other prisons in Albania.

On the other hand, it is much worse, it is a mess in itself, when you already have prior knowledge about that cursed prison where you are being put. It is an inevitable shock, caused by fear, by terror. Even in your mind the inevitable question tortures you: “Will I be able to get out of there alive or as a corpse, wrapped in a stinking blanket, dragged, like a shaggy animal towards the pit of a lost grave, without a sign or a name, where your people will never be able to come to shed at least two tears or put a bouquet of flowers on you”? Therefore, it takes a rare endurance, an epic manhood, to withstand the passage of that fatal door with your feet from the beginning.

The echo has carried the name “Burreli’s Prison” throughout almost all of Albania, since the time of the red dictatorship. This name, for Albanians, was synonymous with hell and continues to be so in people’s minds today. The bad seems to live longer than the good, because humanity, in its life, has seen more evil than good. And especially under the communist dictatorship, which was a more savage and inhumane dictatorship than Hitler’s, also due to the fact that it fatally lasted much longer than the black one. Here’s a fact: in their book entitled “The Black Book of Communism”, thanks to studies and documentation (even incomplete), the authors have concluded that the red one has eaten 86,000,000 victims. While the black one, almost ten times less, perhaps also due to the fact that its lifespan was ten years shorter. The authors of this book are: Courtois-Eerth-Panne-Paczkoęski-Bartosek-Margolin (Editions Robert Laffont, SA, Paris, 1997), six historians, who, from the names, must be French, Polish and Hungarian./Memorie.al