By Ndue Dedaj

Memorie.al / It is surprising how the communist regime never understood the Kosovars who crossed the border to find freedom in “mother Albania”, but sooner or later, declared them one after another enemies, supposedly envoys of the Tito regime, etc. Those who it did not punish, it kept under surveillance, until the end. It did not spare anyone, even when it spent money on their education in universities. Ultimately, there are no unanswered questions. They came as patriots, hoping to escape the Serbian genocide of Tito-Ranković in the 1950s, the confrontation with which had created a symbol of unyielding resistance, such as the writer Adem Demaçi to the philosopher Ukshin Hoti, in recent times.

It is not that they fled from Kosovo, but from Yugoslavia, which was not their country. They sought the maternal paradise here, but found hell, mud and slag of dictatorship. Their pure patriotism, little by little, encountered our proletarian internationalism; they had to love the nation in another “way”, loving the Party of Labor and the “Commander”, the victories of socialism, etc. But, they had communism there, they had come here risking their lives on the border for Albanianness and not for the party.

Here begins the conflict that comes and gets more and more intense between the Albanian state and the Kosovar emigrants. A topic that has never been talked about, and why thirty years have passed since the political prisons fell. Each of them deserves honor in its own right, as much as their common portrait, of resistance fighters of the race, is valuable. A Turkish memorial has been erected in Tirana, with the names of the victims who opposed the attempted coup in Turkey a few years ago; while a memorial dedicated to our Kosovar brothers who were martyred is missing! Titles are given daily by the President of the Republic, but we do not know if any of them have been honored.

Who deserves the title “Honor of the Nation” more than the martyrs? They have been forgotten. They are remembered only by family, friends and comrades, but not by state institutions. A good part of them came from literature, such as the writers: Agim Gjakova, Kapllan Resuli, Adem Istrefi; well-known teachers: Myrteza Bajraktari, Shefqet Kaçaniku, Ymer Llugaliu, Selim Kelmendi, Gani Ratkoceri, Idriz Zeqiraj, Hysen Bukoshi, Ibish Kelmendi; painter Sadri Ahmeti; diplomat Esat Myftari; doctors Jetullah Gashi and Arben Çeta (brother of Anton Çeta); chemical engineer Namik Luci; agronomist Kol Nikçi, etc., judicial processes that took place in Tirana, Durrës, Berat, Fier, Lezhë, Mirditë, etc.

There is a long list of Albanians from Kosovo convicted here, much longer than one might think, although no one has taken the trouble to compile it in full. Some came from prison to prison, had left Tito’s prisons, hoping that this was the “Promised Land”, but here they were again awaited by prison and exile, although not a few of them were allowed to continue their higher education at the University of Tirana, perhaps with the intention of embracing the Party line, which did not happen.

Higher education would have made them more knowledgeable, but it would not have made them communists. Agim Gjakova, the most famous of them, as we read in the notes about his biography, had fled in the 1960s, because he had been a strong voice for the rights of the persecuted Albanians there and this was a strong card, to be welcomed here, but it would not be long before he also aroused discontent in Tirana, with his non-conformist literary work, which shows that totalitarian states react the same way to independent intellectuals.

At the same time as the young idealistic nationalists were flocking here from Kosovo, the star of one of their brothers from Mitrovica, Ramadan Çitakut, was fading in Tirana. He participated in the founding of the Albanian Communist Party (1941), in the main political and military events and formations of the War, after the liberation he was Minister of Finance for six months in 1946 and Ambassador of Albania to Belgrade, until 1948, to then suffer long oblivion due to the political clash with Enver Hoxha, who now called him; “a man of the Yugoslavs”.

Both the Albanian-Yugoslav political friendship, as well as the later hostility with Yugoslavia, brought persecution and even victims in the ranks of the intelligentsia. Thus, in 1945, the Prizren professor Kol Margjini, who graduated in Vienna, was arrested after thirty-some years of service in the country’s high schools and surrendered to the Serbian authorities, where he died in prison after five years. The linguist Selman Riza, who today has a statue in Gjakova, did not escape the “bilateral” prison either.

Researcher Aleksander Meksi writes that due to his deeply patriotic political activity, he was imprisoned in 1945 in Tirana, just a few days after returning to Albania, where he had come to escape the Serbian genocide. He escaped that case without being extradited to Yugoslavia, but this was not avoided in 1948, where after spending three months in Tirana Prison, the Albanian communists extradited him “as an anti-Yugoslav Kosovar”, to be tried by the Yugoslavs. Professor Riza spent three and a half years in Yugoslav prisons and only in December 1953 was he able to return to Albania, where he joined his family in Tirana.

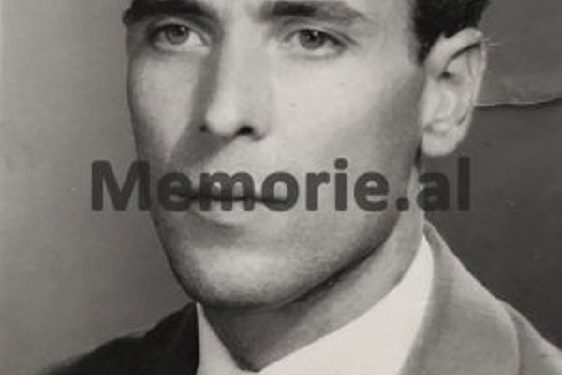

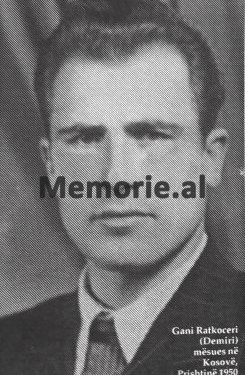

Among the first to cross the border into Albania, in October 1951, was the “Teacher of the People” Gani Ratkoceri (Demir), born in a village near Pristina, sentenced to ten years in prison for agitation and propaganda in 1978, gaining his innocence after serving half of his sentence. He has made his memories of the political ordeal in Albania public in the books he has written and in interviews, where he talks about the agreement between the UDB and the State Security, about the punishment of Kosovars, etc.

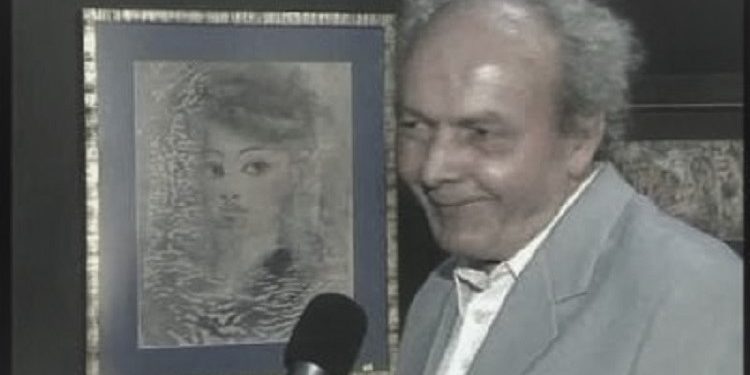

Ymer Llugaliu had left Kosovo in 1958 and sought political asylum in Albania, where after completing his higher studies at the Faculty of History and Philology in Tirana; he was appointed a literature teacher at the Rrëshen gymnasium and then transferred to Kurbnesh, where he was arrested for agitation and propaganda in 1976. The writer Agim Gjakova conveyed his departure from life with these words, on June 13 in Podujeva: “Ymer Llugaliu was one of the purest and most dignified figures in Albania, in freedom or in prison, who held his Kosovar identity high”.

Shefqet Kaçaniku from Prizren, also a literature teacher, came to Albania to escape the oppression of the Yugoslav regime and ended up in the political prisons of Albania. In October 1975, the Lezha Court sentenced him for “agitation and propaganda against the popular government”, to ten years in prison. It was the easiest accusation to “prove”, three lying witnesses were enough and your fate was no longer in your hands. Selim Kelmendi, another prominent name, a literature teacher at the Fushe-Kruja high school, was convicted by the Supreme Court in 1983, on the charge of being involved in a hostile group that was allegedly going to assassinate Enver Hoxha when he came to inaugurate the Kruja Historical Museum.

A few years after his conviction, he would die in Burrel Prison, under unclear circumstances, without being given hospital care. They were pure patriots, excellent professionals, unyielding to bureaucracy and, as such, made a difference to the very time that was “bowing” to the party state, which took away the freedom for which he had fled his homeland. “There were also those who did not go to prison, but remained in the shadows and under surveillance their entire lives, like Haki Osdautaj, a history and geography teacher at the ‘Bajram Curri’ high school,” writes researcher Ismet Balaj.

After we went to Kosovo schools after 2000 and met with teachers and students there, we understood the Kosovar martyrs here even better, because they were not only passionate teachers, but also chief missionaries of the Albanian language. There, teachers had suffered in Milosevic’s prisons, for the “brotherhood” (fullness) of the Albanian language. Not only intellectuals escaped from Kosovo, but also many ordinary people, who were sent to the emigrant camp in Seman (Fier), where they were subjected to Bolshevik “forms of education.”

It could be said that they had fallen from the rain into the hail. But it wasn’t just Kosovars who came here; there were also many who fled to Kosovo, mainly to go to the West. The poet Martin Camaj in 1948, the Shkodran teacher Xhevdet Hoxha, who left the class he was teaching in Rrëshen and fled to Yugoslavia, in the mid-1960s, etc. According to a CIA report, about 10 thousand Albanians had fled to Yugoslavia after World War II, because they didn’t like the government of Enver Hoxha.

Kosovars with university degrees were swallowed up one by one by Burreli, Spaçi, Qafë-Bari and other political prison camps. Many of them were left without families. The party propaganda was dizzying, on the one hand it made films about teachers as “Commissars of Light”, on the other hand it imprisoned the cream of the country’s intelligentsia, priests, teachers, writers, translators, directors, painters, journalists, engineers, etc. The screens were filled with heroic images of the former, while the cells were filled with the regime’s ill-wishers and opponents, away from the eyes of the public, local and foreign media.

The trials of the enemies of the people who had come as brothers were among the most “exemplary”, as the jargon of the time said, to make others remember them. It is worth noting that all of them were learned men, which aroused the envy of the mediocre people around them, who did the only “craft” they knew: spying on them. Those who participated in their trials, although often behind closed doors, speak of the argumentative force, the culture of expression of the accused, openly challenging those they faced; in reality, only a judicial farce was being played out there, since the decision had been made beforehand in the offices of the Central Committee of the Party.

One might ask why so many trials and convictions of Kosovar intellectuals and others so “late”? For the regime, not only liberals in literature and art, putschists (so-called) in the army and alleged saboteurs in the economy were dangerous, but also teachers and poets, the most fragile beings in this world. For the dictatorship, they were just as conspirators as major generals. Therefore, in 1977, Vilson Blloshmi and Genc Leka, who taught the children of Librazhd and wrote poems like “Saharaja” etc., were sentenced to death. In 1979, two journalists from Radio Tirana, Fadil Kokomani and Vangjel Lezho, were sentenced to death, together with Xhelal Koprencka, to be executed with Havzi Nela, in 1989.

Meanwhile, Albanian dissidents in Yugoslavia were sent to their “Spačina” named Goli Otok, on the dry Croatian coasts, cursed and in the poetry of Kosovar poets. The socialist system felt in crisis throughout the East, so it did not stop killing the elites, just so that the power would not fall. And yet, not a single word, memorial, documentary, monograph, except for a few writings, interviews or books by those who survived. Perhaps a minute of silence at one of the meetings of the two governments, of Albania and Kosovo, would be the first sign of an intergovernmental tribute to the emigrants saved in their own country.

In the case of the teachers from Kosovo who worked in Albania at the time of crisis and the dissolution of the socialist camp, their role would be better understood if it were taken into account that teaching had been a tradition among Albanians on both sides of the border, since the beginning of the 20th century, often disregarding borders. In Krumë i Hasit, in 1928 the boarding school “Kosova” was opened, where children from Gjakova, Prizren, Kukës, etc. were taught. In Tirana, a school is named “Ahmet Gashi”, in honor of the distinguished professor, the well-known geographer Ahmet Gashi, who had taught in Prishtina, the “Normal” of Elbasan (its director) and Tirana – the author of the first map of ethnic Albania.

Ernest Koliqi’s initiative to open Albanian schools in Kosovo is well-known, sending over 200 teachers to the Liberated Lands in 1941. It was a time of occupation and the fates of Albanian communists and nationalists would intersect. Fadil Hoxha, born in Gjakova and educated in Elbasan, together with other Kosovar teachers, returned to Kosovo (teacher in Hogosht of Gjilan), from where he was involved in organizing the Anti-Fascist War and after it was elected Speaker of the Kosovo Assembly.

Meanwhile, the nationalist teacher from Mirdita, Zef Vorf Nekaj, who had served both in Albania and Kosovo, would become a professor in America. In the 1970s, professors from Tirana, such as Eqrem Çabej and Aleks Buda, would teach at the University of Prishtina. But there are also many other cultural-educational indicators that prove that the school often succeeded in being “together”, even when politics was not involved. Above all, the Albanian language, the national flag and the Homeland itself were shared./ Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)