By Uran Kalakulla

Part Fourteen

Nazism and communism

Memorie.al / Nazism lasted 12 years, while Stalinism lasted twice as long. In addition to many common characteristics, there are many differences between them. The hypocrisy and demagogy of Stalinism was of a more subtle nature, which was not based on a program that was openly barbaric, like Hitler’s, but on a socialist, progressive, scientific and popular ideology, in the eyes of the workers; an ideology that was like a convenient and comfortable curtain to lie to the working class, to lull the sharpness of intellectuals and rivals in the struggle for power.

One of the consequences of this peculiarity of Stalinism is that the entire Soviet people, its best, most capable, hardworking and honest representatives, suffered the most terrible blow. At least 10-15 million Soviets lost their lives in the torture chambers of the KGB, martyred or executed, as well as in the camps of the Gulag and others like them, camps where it was forbidden to correspond (in fact they were prototypes of the Nazi death camps); in the mines in the ice of Norilsk and Vorkuta, where people died from cold, from hunger, from crushing work in countless construction sites, in the exploitation of forests, in the opening of canals and during transportation in lead-lined wagons, or in the flooded barns of the death ships.

Continued from the previous issue

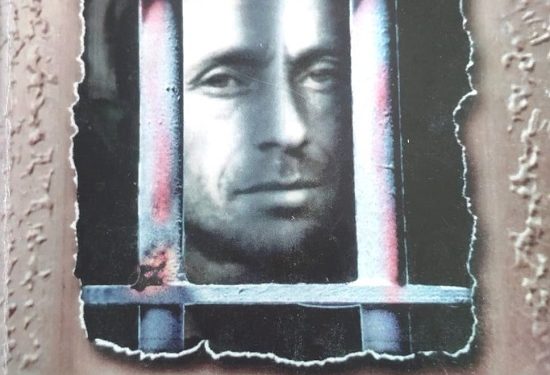

Dreams in the miserable isolation of the cell are like an escape from that misery, like an effort to prevent despair and gloom of the soul from suffocating you, to escape, as much as possible, even though fantasy, the world of darkness, as long as you understand that you are still alive and your eyes, like the soul, desire light! Dreams are like a hygiene of the soul and, why not, of the mind. But, alas, one should not exaggerate because, from a good, they have the risk of turning into a great evil. It is not for nothing that our people say that wisdom and madness are not far apart.

My mother, a very wise woman, seeing me lying face down on my books until the hours after midnight, making sleep forbidden, would always say, desolately, when the occasion arose: “The mind, son, is a grain of wheat”!

The Trial

Finally, the day of the trial came. Should I be happy that that long time of endless dungeons was ending? And it was not a few months, but 14 months of complete isolation: 7 months in the dungeons of Durrës and 7 and a half in those of Koç, in the old prison of Tirana. But can one be happy that he is appearing before the court, to “give an account”, as if we really owed the judges anything? A curiosity took possession of my soul, along with a feeling of sadness, this also tinged with a natural revolt. Then a bad, ominous premonition. It was as if my heart was telling me that my trial would not go well, but would, without a doubt, be a path full of thorns that would make my body bleed.

And then, after the trial, what came? A great unknown, even if I were not sentenced to death, as my heart told me. Death? But why?! What had I done?! Had I killed someone? Or had I blown up some important state facility? By death, only because I was the leader of a group of young men, or boys who did not want to harm anyone, but rather fervently desired the freedom of the people, the maximum alleviation of their suffering, the elimination of injustices, the elimination of state crime; why did they want democracy and social justice?

It was true. It was a right that the entire civilized, democratic world had. But did the communists eat wedges in this direction? No, they were the spirit of denial of all this; with all the evil that followed. And we were under communism, even that of the Stalinist variant! And we knew that Stalinism, and especially with the even more petty variant of Albanian Enverism, all logic and sense of human justice, did not hold water. They had a logic turned upside down. And as for human feelings, they didn’t know where home was.

If I hadn’t been sentenced to death, I would have been taken to prison and there I would have joined my comrades and thousands of others in camps and prisons. At least I would have had company, because the constant loneliness and isolation in the dungeon, with all the severe deprivations that followed, had begun to wear on me, despite my strong will and spiritual endurance. And there, in the labor camp or in prison, I would have read a newspaper, I would have had books, a pencil and paper to write with; to write to my family and to receive letters from them. I would have had the opportunity to meet my beloved and young son, my dear wife, mother, brother, sisters and, perhaps, even cousins or friends, if the latter were willing to come and see me. Then I would see the sky, maybe even grass, flowers and birds.

And, anyway, I would hear human voices and not the shrill screams of hysterical and cruel interrogators, or the incoherent screams and filthy curses of animal captors. Perhaps the food would also be somewhat better, because I had heard, when I was still free, that the conditions of prisons and labor camps were no longer those of the past. And, perhaps, I could also write, of course with tricks and in secret, my future works, which there, in the solitude of the dungeon, were taking shape in my mind, tormenting me more than satisfying me spiritually, like that child in the mother’s womb whose time has come to come to life, but cannot, causing either the death of the mother, or of itself, and always with great suffering and pain.

And I say this, it is not my fantasy at all, but it is a bitter reality, which has been experienced by all those who have the desire to write, to bring out something of their own in the field of knowledge or art. At least even those who seek to fix their sufferings described on paper, as a testament to the hellish life that they were completely unjustly destined to experience. August 8th came, the first day of our trial. They had shaved and shaved us the day before and had made it possible for us, dressed like that, to look something. They did not want people outside to see us, how we had been reduced. They supposedly wanted to maintain the image of humane treatment even in the dungeons of the investigation, since such treatment had acquired a very bad reputation (and rightly so).

They tied us up and put us in a truck with raincoats and curtains in the back, so that we could not see or be seen by passersby. And, between us, a world of accompanying police, armed to the teeth, as if we had wings to fly or were strong and trained, like Hamit Matjani and his friends. Even if they had let us go at all, we would probably not have been able to take even a hundred steps, because we would have collapsed in the street, from exhaustion. In addition to the police, we were also accompanied by a Sigurimi colonel. This meant, in my mind, that our group was important and that we, its members, were not doing our job well at all. And me as its president?

The trial was to be held in the Tirana District Court building, which was then on “Rruga e Durrës”, where today a multitude of notaries are swarming like flies. They took us up to the fourth floor, to room number six, and seated us in two benches of the accused. When I saw number 6, I don’t know why I remembered Chekhov’s shocking novella, which I spoke about earlier. The hall was full of people, but those who had come to assist at our trial were neither our relatives, nor our well-wishers, nor our comrades. They were all invited, and all were either agents and collaborators of the Sigurimi, or devout and fanatical members of the party.

Looking around, I noticed several astonished faces that I did not recognize at all. I noticed that they were indeed looking at us with curious eyes, but all with anger, resentment, and sarcasm, with their evil smiles. They seemed to me like a pack of wolves, which, if let loose against us, would rush to curse us, just as they had wanted to and had shouted at almost all the previous trials of “enemies of the people”; since 1945 onwards, without ever having had their fill of human blood. They were such faces that, if the judge asked them about the extent of our sentence, they would shout in chorus, with all the gust of their black soul: “To die, to the lytaar”!

Before the jury had even entered the courtroom, a few individuals approached us, even these strangers. Three or four of them told us that they were our lawyers. At that time, the legal profession was supposedly functioning, it had not been abolished at all, as it happened later. Only I was left without a lawyer. In fact, I had asked, since such a thing was imposed on me, lawyer Dilon, not because I had heard about him, that he also had social-democratic views (how had he survived then, without being arrested?!), but because (always upon hearing him), I had learned that, among all the others, he had shown himself somewhat more courageous, certainly in ordinary trials and, perhaps, in some simple political trial, such as agitation or an escape attempt, of some simple kid. But, of course, here too with a pronounced “moderation”. That there was no joking around with the trials, which were just a kind of stage play of the Sigurimi and nothing else.

They told me that lawyer Diloja had not accepted. I wondered: how could he accept? I knew this before, too, which is why I had insisted on it. That way I would have been able to defend myself, as I had intended. But, even here, I couldn’t go, because, finally, a man close to old age approached me and, all scared and in a low voice, introduced himself as my lawyer, of course, since I had seen him before, he went and got permission from the colonel, who had accompanied us to the court.

– “I am your lawyer”, – he said with a trembling voice.

– “Who are you, what is your name, Mr. Lawyer”? – I asked him.

– “My name is Dhimitër Popa, from Durrës…”!

– “Excuse me, Mr. Lawyer, but I didn’t ask for you, but someone else”. – “I know, but he couldn’t come, because he was busy”.

– “Thank you for the service you offer me, but I have decided to defend myself.”

The lawyer remained sad, as if ashamed. Was he worried that he would thus escape the monetary reward from my family? Or (not to get his revenge), out of a human feeling for me, when he saw me as a young man and was familiar with all that pig of an accusation that was being made against me? After a while, the lawyer came even closer to me, almost to my ear, so that not even the policemen who were on all sides of us (in the dock, between us) could hear him and said to me:

– “Zarifi assigned me, because we are also friends. And he paid me.”

Zarif was my older sister’s husband, by birth. He had loved me very much and had always respected me, just as I had him. He also had no good relations with the “popular government”, as a landowner who had once been in Myzeqe, a kind of bey. For the great sake of Zarif, I accepted this lawyer, but immediately after that I asked him:

– “Have you seen, Mr. Lawyer, the indictment, especially the part that concerns me”?

– “Yes, I have seen it”.

– “Listen here! Don’t bother defending me in vain, about what Article 73 contains, the first paragraph of which speaks of agitation and propaganda. The group’s case has been brought before the investigator and I have signed the minutes. The fight we have to wage is about the other two Articles, 76 and especially 64. The latter speaks of treason against the Fatherland and we are accused of having made attempts, or conversations, to supposedly connect with foreign agencies. Do you understand now? Here is where you and I should aim. To save what can be saved, because it is known that without getting wet, we can never get out. The point is not to drown at all”.

– “Yes, sir, yes,” the poor and very frightened lawyer replied, “but you don’t know that ‘these’ have Article 64 like salt and pepper, which they throw everywhere”.

That’s what the lawyer said and he walked away from me, never to come near me again! Then I called to my mind:

– “Either I’m completely confused and don’t understand what’s going on, or this poor old man is confused out of fear and doesn’t know what he’s saying?! And, from that moment, I decided to defend myself mainly by myself and only by myself. That night, during the entire trial, my lawyer, but also those of the others, spoke only once, before the presentation of the pretext, on the fourth day of the trial. My poor lawyer, read only a page of a handwritten school notebook and I didn’t even understand what he said. I only remember that he finished his speech, saying that he was deeply sorry and that he asked for mercy, since he had an old mother, a young wife, a small child to raise and he himself was young. Come on, hut, where did you gather us!

Finally, the jury entered the courtroom. The guests and the policemen stood up. They forced us to stand up too, that is, to honor exactly those who would condemn us!! Personally, I didn’t like it at all, I don’t know about the others in the group. I believe that they must have thought the same as me. Because we were there for a common assessment. But, more than anger, curiosity came into play. Who were the people who made up this jury? I had known the prosecutor since the investigation and had had many debates with him, even theoretical ones about Marxist theory, in which I caught him off guard several times. And he was very surprised that I knew their Marxism-Leninism, with history and works.

Almost certainly, that military prosecutor, with the rank of major and called Sami Kapllani (originally from Mallakastra), must have felt sorry that I, instead of being a prominent party secretary, was in prison, as a defendant for anti-revolutionary activities, because (like all his comrades of his kind), he believed that, in the whole world, the only true revolutionaries and humanitarians for the poor were them, that is, the communists, and that it was not possible to be completely with the poor people and with the people in general, without being a Marxist-Leninist!

I don’t remember who stood up and mentioned the names of those three people who made up the jury and the prosecutor, and even the secretary: a young girl, very charming, brunette, in a red dress. The poor girl, seeing us lined up like that, all young, before the trial began and knowing what awaited us, openly showed her pity on her face and in her gestures; without worrying about the security guards who filled the hall. Maybe she could have been one of their daughters or sisters, but she didn’t have the black soul like them. We were being tried by the Military Court of Tirana. Why a military court, when we were all civilians? But because that was how it was then. “Enemies of the people” should have been punished by a military court, more strictly. Sooner or later, the communists abolished this rule.

The head of that panel of judges was Llazi Polena, a weak old man, with a face as wrinkled as a dried fig, with a large forehead that seemed to precede the lek’s head; some large ears, like opinga; a thin, red neck, like a turkey; with a pair of colorless eyes, as if made of ice, cold in their cynical gaze and without any human light. I don’t know how to put it more precisely! I didn’t like that man from the beginning, because he seemed to me cold as a corpse, ominous as a shroud and his whole appearance resembled a dead man, held with difficulty in a chair. There was something macabre about his being: something that had just come from the world beyond the grave. I swear, if I approached him, I would surely smell musty, like the dead, freshly laid in the grave.

The other member of that kind of jury was Lieutenant Colonel Reshat Nepravishta. He wasn’t bad at first: a tall, somewhat rusty guy, just like the people of the Myzeqar are generally. The uniform didn’t look bad on him, but he had an attitude somewhere between cockiness and arrogance and an ironic smile that made him seem not only unappealing at first, but quite disgusting, like a hyena. And when he saw us or, when he sometimes intervened in the debate, he wanted to seem like he was something, supposedly some kind of intellectual. Years later, when I found out that he was also a writer, I don’t know why I felt a sick feeling in my stomach. I said to myself: I am an “engineer of souls”, as Stalin had called his writers (i.e., those who build souls), I am a military judge, whose duty is to kill souls. Come on, take on this job then?!

The other was a first captain. I didn’t quite understand his name or his surname, Mexhiti. And I didn’t even know where he was from. I didn’t even hear this captain’s voice, because he never spoke for four days in a row during our trial. I didn’t understand what that man wanted to do in that middle. Or, just to complete the number! I believed this. I think he was elected “judge” or “people’s assistant judge”. He was a rather young man, with a stocky body, a full, red face and a red scarf that constantly fell on his forehead. Of course, he had to say goodbye to his glass of rakija. He didn’t speak, but just looked and smiled. I don’t know for sure: because of the president’s mistakes, which we sometimes found dull, or because of the joy he felt at being present at the sentencing of the seven “enemies of the people”? Once the acceptance ceremony and some other even more pointless things were over, the prosecutor was finally given the floor, who read the indictment.

And what was not said in that so-called indictment: the favorable international situation for the socialist revolution, almost on a world scale (as if he wanted to explain the Trotskyist theory of “permanent revolution”), that American imperialism was coming to an end, that it was the countries of the third bloc (with India at the head) that would now lead the world (not America), that both imperialism and Khrushchev’s revisionism were allies among themselves, but they could not bear to do anything to Enver Hoxha’s Albania, that they knew and were breaking their heads, that both of them, even a little, would give up, that the situation inside the country was excellent, that party-people unity was at its peak, that internal enemies were taking the blame for the party and the people’s power, and full of these Enverist expressions.

And finally, he got down to business with us, saying that we were agents, enemies, traitors to the Fatherland, bourgeois and capitalist scum in the happy socialist society, that we were going to put a pickaxe on the country of the great victories of the people, and other such nonsense. And after that, he started accusing us one by one. Starting with me and up to Kahremani, he made our black biography, calling us; “wild and dangerous enemies, assassins of people’s democracy” and, in turn and without sparing; so many accusations, that I, the first, began to not recognize myself anymore (of course, the others too).

But all this phantasmagoria was read quickly, thankfully so much so that, at times, it was not understood at all. Either the prosecutor did not know how to read what he had written, or others had written to him and he had not had time to read it, once or twice before! “Come on, prosecutor, come on, for your own sake”! Life showed that my first and last impression of him was not wrong, because years later I learned that this very prosecutor had himself ended up in prison: as an ordinary person, as an embezzler of socialist wealth, that is, as a thief! Come on, prosecutor, come on! The evil of your head and of your socialist or Marxist-Leninist-Enverist morality”!

They called Zeqir to speak first. Perhaps, even though he had been the first arrested among all the rest of us. And, despite the fact that he was tarred after the sentence, he spoke well in court: skillfully and did not burden any of the rest of us. I do not remember well that I spoke to him. Someone says that I spoke well, that I spoke for about four hours, that is, my dialogue with the jury lasted that long. I knew very well that all the bad things I had were from President Llazi, that he had taken on, in my case, the role of the prosecutor, instead of the president, who, theoretically, should maintain the balance between the accusation; that is, the prosecutor who represents the injured party, and in our case the state, and the accused, the “injurer”, the guilty party, which was me and my friends.

I remember well that my apology was mainly to refute, as I have said before, the accusation on the two dangerous articles, 64 and 76. But, no matter how much I spoke and defended myself with logic and arguments, in the communist courts it was useless. They did not eat wedges at all. The decisions had been made elsewhere and Llazi and his friends, they were just a kind of simple joke, as I have said somewhere before in these pages. But the evil of that certain whistle-blowing and shit-souled chairman, was not so much in his competence, but in his pleasure in sentencing me, which was clearly visible.

As far as I know from criminal and judicial procedure, it is the prosecutor who first requests the highest sentence. The jury (and that is why it is called such, because it has the duty to judge, that is, to weigh), either leaves the prosecutor’s request in place, or lowers it, more or less. But Llazka and his friends, in my case in particular, did the opposite: for me the prosecutor requested a sentence of 25 years in prison, while Llaz raised it to death, by shooting! Should I have thanked this judicial body, that the gene showed itself to be “prudent” and did not decide for me to be hanged? It was clear: I would be punished more severely than everyone! Memorie.al