Memorie.al tells the story of the famous trial that took place in the Japanese capital, Tokyo, shortly after the end of World War II in 1946. Who were the top Japanese politicians and servicemen who came to the dock for the crimes they had committed in Asia and Oceania and the names of the judges and prosecutors of the International Court who assisted in the most sensational process after the 1945 Nuremberg trial in Germany?

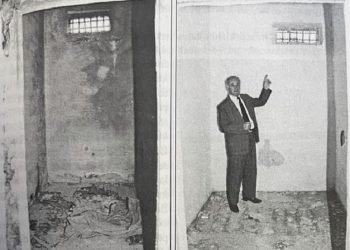

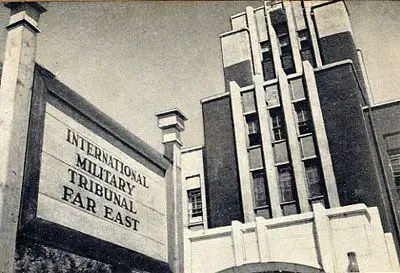

On May 3, 1946, in the Japanese capital, Tokyo, began one of the most famous lawsuits for the conviction of Japanese WWII criminals, otherwise known as The Tokyo Process. The famous trial was organized by Anglo-American and Soviet allies who had fought with the Japanese imperial army during World War II and were familiar with the Japanese army’s barbarism in Asia and Oceania. Prosecutors and judges from other countries, such as France, China, India, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the Philippines, and Canada, will also take part in the trial since the Japanese had invaded Asia and Oceania had badly damaged the colonies. to these states. The process took place in the context of the conviction of World War II criminals. In this context, another international court was being held in Nuremberg, Germany, to convict Nazi war criminals, Japanese counterparts. The arrest and imprisonment of Japanese servicemen and politicians accused of being war criminals were carried out by US forces who had invaded Japan at the time, after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By the order of the International Criminal Court, all Japanese top hierarchs, who were implicated in mass crimes in Asia and Oceania during World War II, were arrested. This category included senior politicians, senior military men, and some ambassadors who had served the Japanese imperial militaristic government during the war years. Their arrest by the Americans was made possible within a few days because none of the accused had fled Japan. They were kept in a high-security prison, from which they could not escape.

The beginning of the court

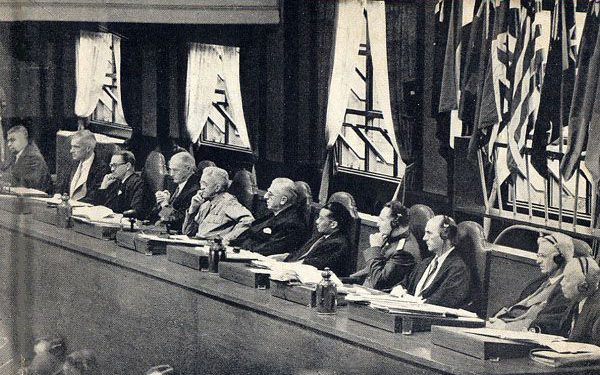

The Tokyo trial began on May 3, 1946, and was held at the Tokyo Palace of Justice under extremely stringent security conditions. International prosecutors assisted in the process of denouncing the crimes of the Japanese were: Joseph Keenan (USA), Justin Mansfield (Australia), Henry Nolan (Canada), Hsiang Zee Chun (China), Robert Oneto (France), Govinda Menon (India), Frederick Mulder (Netherlands), Roland Quilliam (New Zealand), Pedro Lopez (Philippines), Arthur Comins (UK), and Sergey Golunski (USSR). The international judges who would sentence the Japanese war criminals were: William Wueb (Australia), Eduart McDowell (Canada), Mei Ju Ao (China), Henri Bernard (France), Radhabinod Paul (India), Bert Roling (Netherlands), Harvey Northcroft (New Zealand), Dolphin Jaranilla (Philippines), Lord Patrick (Great Britain), John Higgins (USA), and Ivan Zarajanov (Soviet Union). Japanese criminals would face serious charges such as the deportation and massacre of prisoners of war in camps, the bombing of cities, Shanghai, Nanjing, Manila, and villages with unprotected civilians, the use of torture and the dishonoring of women and children. , the use of poison gas and bacteriological weapons, etc. The perpetrators of these massacres and major crimes were: Japanese Prime Ministers, Hiranuma, Hirota, Koiso, Tojo, Foreign Ministers, Matsuoka, Shigemitsu, Togo, Araki War Ministers, Hata, Itagaki, Minami, Navy Commanders, Nagano, Shimano, the six Imperial Army generals, Doihara, Kimura, Matsui, Muto, Sato and Umezu, the two ambassadors Oshima, Shiratori, Emperor Kido’s advisor, Okava radical theorist, Admiral Oka, Colonel Hashimoto. The only ones not tried in the Tokyo Process were Emperor Hirohito and Prince Asaka, who was protected by the sacred royal command. In the trial, about 20 witnesses testified who told prosecutors and judges the unprecedented crimes committed by the Japanese hierarchs. The trial also saw plenty of evidence implicating senior Japanese hierarchs in many violations of the rules of war and peace treaties. None of the Japanese criminals who appeared before the court accepted the war crimes charges made by international prosecutors because they thought they could have relief from the many changes that were made. But the charges they disputed were substantiated during the trial by numerous witnesses and film evidence taken directly from the scene.

Classification of war crimes

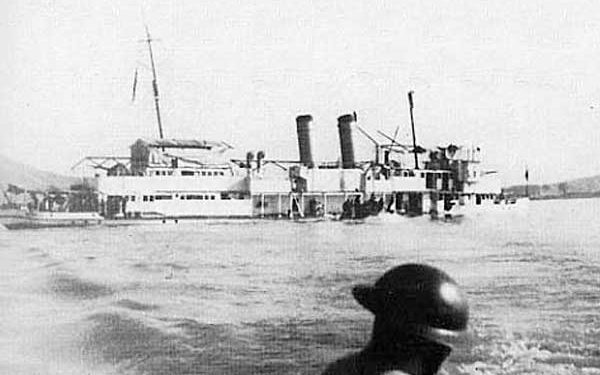

The war crimes committed by the Japanese military during World War II by the International Court of Justice for the punishment of war crimes were classified into several categories. Category A crimes, crimes against peace B, war crimes and C, crimes against humanity. More implicated in these crimes were the more senior Japanese generals and military men responsible for the mistreatment and killing of prisoners of war in labor camps in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and others. These crimes included the bombing of Chinese, Filipino, Korean cities, and the bombing of the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. This category of crime also included unprecedented massacres of Chinese citizens with bayonets on the Yangtze River. , which was also documented by photos taken from the crime scene. But even though the Tokyo Process has had a great echo around the world, a good portion of Japanese war criminals have remained untried or escaped trial by escaping and participating in post-war cabinets in the pro-Allied Japanese government, such as Kish, Kuhara, Ajukava, Nishio, Ando, Kodama, Aoki, Tani, Amo, Suma, Sasakawa, etc.

Judgment was given by the court

After two-and-a-half years of litigation in Tokyo, members of the Supreme Court for War Crimes made the final verdict on Japanese WWII criminals. As a result, Tojo, Muto, Doihara, Kimura, Hirota, Itagaki, and Matsui were sentenced to death. Araki, Hashimoto, Oka, Oshima, Sato, Hoshino, Minami, Suzuki, Hiranuma, Kido, Shimada, Shiratori, Hata, and Umezu were sentenced to life in prison. While Shigemitsu was sentenced to 7 years in prison, and Togo to 20 years. The seven death row inmates were hanged on the night of November 13, 1948, at the Sumida Prison gym in Tokyo. Most of the other inmates died in prison because some of them were elderly and could not escape the illnesses that plagued them in their cells. At the end of the Tokyo process, many Japanese were very satisfied with the war crimes court’s rulings. Others who believed that the Japanese militaristic dictatorial regime had been good and that they themselves had lived well under such a regime, did not welcome the court’s ruling. They honored their leaders who had just been executed. Likewise, the international reactions to the Court’s sentencing were varied: those who had suffered under the Japanese imperial occupation held that decisions could be even tougher (more death sentences). Others responded by saying that the decisions taken by the International Court were fair. But the sentences against Japanese war criminals continued even later. In China (the state that suffered most under the Japanese military boot), 13 trials took place, of which 504 Japanese were indicted for war crimes, and 149 were severely convicted. From his imprisonment, there were those Japanese criminals who “escaped” the Tokyo court’s ruling. Matsuoka and Nagano died of cardiac arrest in prison, while Okava was described as mentally ill and taken to psychiatry. But after the “American invaders” left Japan, he was released from psychiatry. The International Court of War Crimes ruling upheld the nostalgia of the Japanese militarist dictatorial era exercised during World War II.

The precedent. After the Nazis and the Japanese, Saddam and Milosevic were also indicted. From Nuremberg to war criminals in the former Yugoslavia and Iraq

After the end of World War II, the Anglo-American, Soviet, and French allies decided to convict all war criminals, the German Nazis, and they set up the International Tribunal for the War Crimes. In this context, the famous trial of the Nazi hierarchy, such as Hitler’s ministers, army chiefs and commanders of German concentration camps, began in Nuremberg, Germany. From this process, which took place from October 1945 to November 1946, by the Presidency of the War Crimes Tribunal, the following decisions were issued: Gering, Ribbentrop, Keitel, Calterbruner, Frank, Schreiner, Frick, Jodell, Sankel, Rozenberg, and the Incar by Death. Hess and Funk were sentenced to life in prison. With 20 years in prison, Shaper and Rider. Donitz and Nojrat were sentenced to 12 years in prison. Papen, Fritsche, and Shakt were acquitted. Hitler’s Nazi Party Secretary Borman and the Gestapo chief Heinrich Myler were sentenced to death in absentia. It was the decisions of the Nuremberg Trial that led to the conviction of all war criminals around the world and their criminal actions to be condemned by the world. After the end of World War II, there were other terrible wars in the world that terrorized the entire globe. After the collapse of the apartheid system in South Africa, many high-ranking state officials (whites), accused by the colored population of mass slaughter and torture in prisons, came before the dock for crimes race against Africans. At the conclusion of the trial, many were sentenced to life in prison. Rwandans were also tried in Rwanda for the massacre of 100,000 Tutsi members within a month. But the most important process in post-World War II Europe is that it is still underway in The Hague against Yugoslav politicians and generals (Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats) who are facing charges of crimes against humanity in the civil war. in Yugoslavia in 1992-1999. The trial also saw former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, who authored ethnic cleansing in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, and the dictatorship that followed in Serbia from 1989-2001. But he died in his cell and the trial against him was suspended. In parallel with the Serb war criminals in Iraq, the trial of former dictator Saddam Hussein, accused of massacres of poisonous gas by the Kuwaiti and Kurdish populations.

Experiments with human troops in Japanese camps were never punished. General Ishii’s Unit 731

In 1989, construction workers in a suburb of Tokyo (Shinjuku) made a valuable finding that shed light on crimes committed during World War II: under the asphalt layer they were removed, they encountered a massive mass grave, where there were thousands of human bodies adjacent to each other. Pressure from public opinion forced the Japanese government to pay close attention to one of their ancestors’ biggest secrets. Near the site of construction during the Second World War were precisely the laboratories of Lieutenant General Shiró Ishii, chief of unit 731 – a special squadron tasked with developing the Japanese biological weapons program. It tested biological, chemical and bacteriological materials on the bodies of the Chinese of Manchuria, brought from a labor camp there. By the end of the war, carcasses were thrown into a mass grave until it was discovered by accident in 1989. In fact, five years before the discovery in question, a student discovered, or rather, encountered a second-hand shop in Tokyo, in some old medical records, which were precisely the documentation of experiments with human bodies. Special Unit 731. Documents left there by an associate of this Special Criminal Section contained medical records on the lethal impact that human bodies had on the outbreak or injection of artificially induced epidemic diseases – from the time of injection until death. The head of this unit was Shiró Ishii, who had been an excellent microbiologist in the service of the Japanese Imperial Army, which would soon make a great name and career. As an ultranationalist engaged in the Japanese Ministry of War, he was credited with being the

undisputed leader of the chemical and bacteriological weapons development program. The so-called Zhong-Ma camp also housed Unit 731. This camp was built by forced Chinese workers. In the middle of the camp building was a laboratory with experimental rooms for prisoners. Prisoners who were selected to be experimented, fed, and fattened, to be eligible for the conditions under which the experiments would be made available. The experiments were inhumane. When Ishii ordered a fresh brain from his subordinates for his experiments, he was not doubted. Camp soldiers dragged prisoners, and as one of the victims fell to the ground exhausted, the Japanese withdrew a sword from their waist and beheaded the samurai once. The brain was immediately sent to General Ishii’s lab as the victim’s body was later buried in the camp’s crematorium.

Other similar crimes constituted the daily life in this lab.

In 1986, the former prisoners of this camp broke the silence for the first time. The US Congressional Inquiry Committee, however, heard about 200 witnesses and also investigated the methods of operating Unit 731 in the concentration camp. But instead of shedding light on these crimes, the commission’s official announcement said that documents owned by this unit under General Ishii’s leadership had been handed over to the Japanese government in the 1950s. Experimental experiments with unit 731 were deliberately forgotten by both the Japanese and the American.

General Schiró Ishii died in 1959, never regretting his actions and never being able to access justice. But in the wake of public pressure at home and abroad, then-US Secretary of Defense William Perry in 1993 demanded that the matter be resolved and the documents returned. But nonetheless, the killing of over 3,000 Chinese prisoners in Japanese camps through the biological weapons used by Unit 731 remained completely unexplained./Memorie.al

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)