By Skënder Tufa

Part One

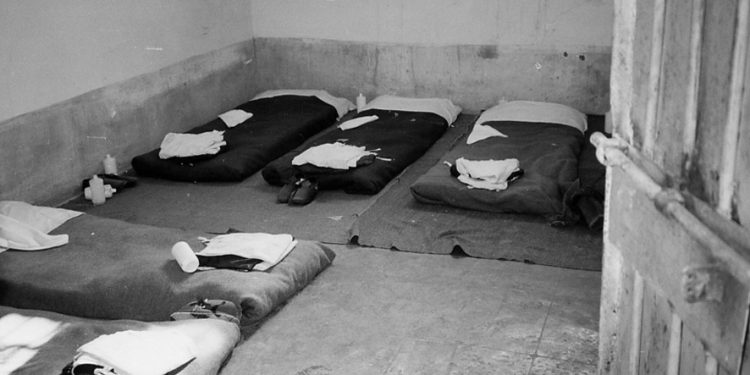

Memorie.al / After the amnesty of 1982 and after the murder of Rexhep Geci, the situation worsened further in Spaç prison, where the police began to tighten internal regime measures with schedules, food lines and the extension of waiting times on the terrace for appeals. At the end of January 1983, we were informed that part of Spaç prison would be transferred. A new prison had been opened near the Munelle Mountain in Puka and laborers were needed for exploitation. The strong and problematic workers were put on the list that would be sent to the Puka mine. The transfer of about 200 prisoners was a great hardship for them, as they had to deliver blankets, sheets, mattresses and dishes, such as; bowl, spoon and gourd, you had to take your personal belongings from the warehouses and get them ready for inspection.

All this, waiting in line accompanied by the “barking” of the police. We were almost ready, when suddenly a strong wind brought a heavy snowfall, which in a very short time reached a meter thick. For that day it was impossible to move and an anomaly created by the situation we were in, made us spend the night worse, since everything had been surrendered.

The next morning, in an environment completely covered in snow, they take us out to the black field and the policemen of Spaç prison, together with those of the escort who came from Tirana, after checking us, chain us two by two, and with our personal belongings in our hands, crawling like that, they put us in cars covered with raincoats. The road was difficult and dangerous, as the snow had made the terrain slippery.

The convoy stopped in Fushë-Arrëz, as the snow there had reached a meter deep and the roads were being cleared by tractors. Kasem Kaçi, a senior official of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and Dhimitër Kristafi, director of the Enforcement of Penal Decisions (director general of prisons), who were leading this operation, directly supervised the temporary cordon, as well as the work to open the road, which had been cleared during the night, but the morning rains had filled it up again.

This was the first introduction, with the cold climate of the prison where we were being transferred. The cars started again and our bodies, crushed, pressed against each other, so crushed under the shock of the potholes in the road, awaited arrival in the next circle of hell.

After several hours of travel, they finally stopped. When we get off, we see that we have arrived at a yard surrounded by wire and soldiers, where cars were taking the mineral extracted from the mine and on its side three buildings, which were inside another enclosure. This was the Qaf-Bar prison. A group of policemen led by a young policeman, who was in the middle of them, approached us and began to check us once again and then directed us to enter the premises of this prison, which was much more crowded than the Spaç prison, but again in the shape of a funnel, beaten by three mountain gorges.

Crushed by the road and gathered by the cold, with the few things we had, we walked laboriously towards that small door, which would take us into the large cave. Prisoners from Ballsh prison (a prison with a climate of extermination, which after the amnesty of ’82, was merged and divided into two parts, one transferred to Zejme in Lezha, and the other here in Qaf-Bari) volunteered to help us, as they knew each other or their friends, always accompanied by police officers and their chief, a young police officer. We settled into the rooms assigned to us.

Entering the apartment and meeting acquaintances, somewhat enlivened us, relieving us of tension, but only for a short time, because the dang-dang that made our ancestors move and, after them, us too, was a commanding sign. “What is this” – I ask Fatmir, my friend, the fellow prisoner of the co-ideal, who had come from the Ballsh prison, a month earlier. – “Çanga, here all actions are done with dang-ding” – he tells me laughing and we continue after the others.

Upon reaching the edge of the stairs where we descended into a concrete-paved field, in front of which were several water taps and in their corner, to the right, a concreted iron pole, where a 200 m/m projectile hung, the Çanga that would replace the voice of the teller Grigor Xarxalli, of Spaç, greeted us. Rushing after the others, we entered a hall with long benches and tables, which was easy to understand as the canteen.

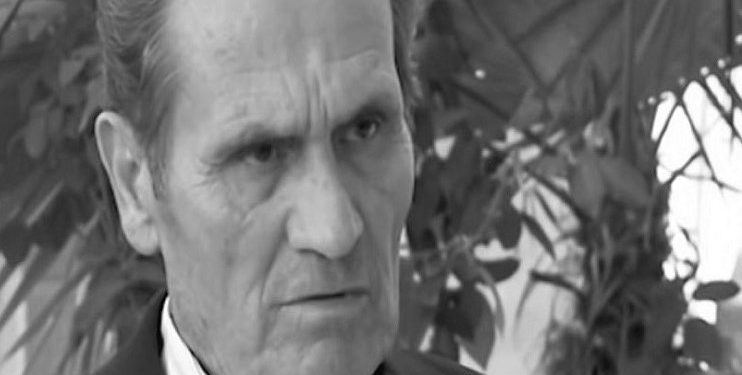

It didn’t take long and the front of the canteen where we had been seated was filled with prison guards and in their center were two officers, an old man in military uniform, Riza Musollari, who was the prison commander and the other who looked like his child of his age, in police uniform, Edmond Caja, who was the chief of the prison police.

They asked for silence because there was communication. The policemen with batons in their hands began to move around the hall, scolding each other threateningly. The police force of this prison consisted of Dibra people, left over from the ordinary prisoners who had been transferred earlier from Bulqiza prison. They didn’t need to be scolded, since their faces were already strangely deformed.

The chief policeman, named Myzafer, was naturally disfigured, a Neanderthal in our time, synonymous with the chief policeman of Spaç, Pjetër Koka. The presentation of the environment and personnel was being done naturally; the reports would retouch the landscape.

The commander officially announced to us that we were in the Qaf-Bar prison, where order and discipline were required and, above all, the work rate was not to be discussed. “Those who break the regulations and do not do the work rate in the gallery will be punished,” concluded Commander Rizai, with four grades of school. Under the fatigue of the road, the biting cold and the threats of the prison commander, the first night would be spent in the “new grave”.

The morning of the new day would find us divided into work brigades and for this they would bring out the entire workforce, so that we would be equipped with the necessary tools, such as; shovels picks, lanterns, boots and hats. In the first shift, three brigades worked underground, production, advancement and armorers.

The extraction of the mineral, in addition to the geological processes, had several other processes, such as advancing by opening a gallery, until the mineral vein was reached, laying rails for the wagons and ventilation pipes, covering the gallery with bodies (armor), and then working to extract the mineral. I was assigned with Nazim Sait and Luka, in the advancement. The gallery was very close to the dormitories. After changing in the locker rooms, we went inside the sled.

Along the entire road, when there was a layer of snow or rain on the surface, it dripped heavily inside the gallery, so much so that when you arrived at the work front, you were soaked. From the entrance to the slope, it was about two km. distance which, in the bad road conditions, the rush of the police and the time needed to complete the norm, was done in half an hour.

The slope was 45 degrees and on one side there was a wagon filled with scrap metal, which was lighter than a cart with a full wagon, which allowed for a controlled descent from above and was heavier than a cart with an empty wagon, which allowed for a controlled ascent. On the slope, there were four horizons (gallery), from where the ore was extracted and the fifth one, which was located at the top, near the auger, was the advancement horizon.

From there we would go another 1500 m., to reach the work front. Our task was to remove the material obtained from the mine explosion and then, to make a pair of barrels, for the next explosion. From the mine explosion, half of an unexploded dynamite mold remained under the rocks, which poisoned the environment, but time was running out.

After the first wagon was filled, the contaminated body provoked the food to be taken out and the red eyes were filled with tears. I had to take the wagon and send it 1500 m. away, to the sloping plane and then take the empty wagon and bring it on the same road. Sometimes Brigadier Bashkim Allmuça would come and give us a hand, but still the work was beyond our capabilities.

After we finished, we had to walk another hour to get out of the gallery, where the others were lined up to return to the dormitory. We changed hastily and, dusty as we were, in a row of two, we entered the prison yard, where we first had to throw a few handfuls of water on our faces, to clean ourselves somehow, and then go to the canteen.

The food was very poor and insufficient to cope with the energy spent in extracting the mineral, this lack of sustenance every day for the exhausted bodies which were dragged away under the threat of the police whips and as if this were not enough, slow-acting medications were added to the food.

Every action was directed by the chief of police, Edmond Caja, who, every time he entered the prison premises furiously, would communicate a new restrictive or aggravating measure. Sunday began to become, under his leadership, harder than other working days, as over 150 percent of the set norm had to be achieved. For the already exhausted bodies, this became more difficult, as Sundays that served to relax the bones a little, turned into days of action!!

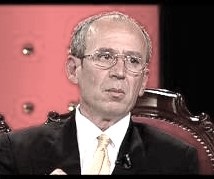

The policemen, ordered and supervised by their chief, became more and more severe every day and after each torture, he, who was “stretched” like a thorn, would be brought in with a police escort into every cell of that prison’s life. Coming from the Police School and raised in the middle of Tirana, this man would not only demonstrate the times, but also the extremely communist upbringing of his family, through which he would make the lives of these people punished by politics as difficult as possible, because they did not belong to it.

Many were unable to work in the mine, due to illnesses acquired from the hard work and inhuman conditions, and this necessitated the construction of a long silo, built of planks, which became a dormitory for these people.

Mark Prendi, a native of Shkodra, would call it “MAUNE” and that’s how it stayed. That dormitory, which was like a refrigerator in winter and a stove in summer, would be wickedly managed by the boss Edmon Caja, who would order the dormitory to be closed from 6 am until 7 pm. The cold in Qaf-Bar reached -18 to -20 degrees.

The elderly and the sick tried to find a corner to protect themselves from the wind and frost, the rains soaked their hungry bodies, who, to save themselves a little, would enter the toilet area and when he found them in the corridors, he would shout at them to get out and the policeman would warn them, sending them as punishment to the most difficult place of service. While in the heat, the elderly and the sick often suffocated from lack of air and collapsed, exhausted.

These measures had their effect, forcing some sick people to ask to return to work. We tried to avoid confronting him every time he entered the prison, since in 90 percent of cases, he would end up in the Technical Office, where the whips did not ask where they were shooting, or in the dungeon. One day, lost in thought, I went out to the concrete square where the shack was and I did not see that he was coming to inspect the dormitory, it was late, I could not turn back.

My face was covered in hair, because I had not yet shaved it and I cleaned it once a month, when we got a haircut. He called me, saying: – “Hey Tufa, why don’t you shave?” – “I don’t shave,” I say, not to contradict him, but to tell him the truth. Touched by the sensibility, after receiving my answer, as a refutation to the police, he orders them to grab me and drag me to the barbershop that was nearby and, after sitting me in a chair, I order the barber to shave me in front of him, without lather. For the first time, the razor on my face has passed violently, ordered by the chief Edmond Caja, without lathering.

The prison command began to economize on food and at the height of the cold, the workers were given, not 800 gr., but 600 gr. Bread, compensated with two small potatoes, often green, while for the unemployed, out of 600 gr., 450 gr. were distributed. Bread, compensated with two potatoes, for which they had to stand in line three times a day, in the snow that often exceeded the length of their unkempt bodies, and those frozen hands that held the aluminum bowl stretched out for soul-sustaining food, formed the image of extreme persecution.

Food that was often used to warm the hands a little and then poured out (after only its smell was fragrant), consisted of 10-year-old, moldy onions and spinach, taken out of the state reserve warehouses. Those of us who had no help were easily distinguished by our hollowed-out faces.

Our work front was interrupted and we were transferred to the production brigade. Once I was working with Lush Bushgjoka. We fill the wagons with the norm and make us go out, policeman Beqir Vrenozi sees us and says: – “Why did you leave the gallery 20 minutes early”?! – “We finished work and left” – we tell him. He reports to the gate and Lushi ends up in the dungeon, my conscience was killing me and I could not accept it, so that my friend would be punished and I would remain untouched. In the evening, when the third shift was getting ready for work, I object to going to work and end up in the dungeon.

In the Qafë-Bar mine, pyrite and blister copper ore were extracted, which were very heavy and to extract them, they worked with fixed wagons. The average weight of a wagon reached 2.5 tons. The norm, from four wagons, would be five wagons, or 12.5 tons per person. Then they transferred me to production, where I joined the group with Dilaver Hysi and Ylmi Çoçka, both excellent people. With great effort, we tried to meet the norm, so as not to clash with the police, but it was often a problem, because we could not find the mineral in the front and for this they had to dig in places dangerous to life. Clashes with the police had to be avoided at all costs.

The arrogance of the police had become unbearable. They did not ask if you were young or old, when they passed, you had to stand up and take off your hat, to honor them. Whoever disobeyed was punished. This had caused many young people to not wear hats even though it was cold. Once at the taps of the changa, Havzi Nela said to me: – “Why don’t you wear a hat, my boy? It’s cold and it makes you sick. You have to take care of your health.” His white eyes, like those of an eagle, and his teeth like beads, at that moment, have long remained in my memory.

In addition to fatigue at work, when our bodies needed a little rest, we had to go to the hall and listen to forced reading. The chief of police, who had gradually taken over the reins of the prison, acted with arrogance, raising his voice more and more. His invention was QUARANTINE. A room was improvised above the bathrooms, where the laundry was located, and all the young prisoners were initially sent to this environment, where they were beaten three times a day by the police, under the direction of the chief, for two weeks in a row. When they entered the prison premises, they were terrified.

Then they put me to work on the slope, together with Bashkim Harun, we had to put the full wagons in and take the empty wagons out of the mine. I was so weak that the shovel with the mineral was heavier than me! Bashkim was also pushing me, although I tried my best, to work as hard as I could. Someone told me; “ask to be weighed, because the mine regulations do not allow a person weighing less than 50 kg to work underground”.

Together with Ahmeti and Fatmir, we go to the doctor, who notifies the guard officer and then comes the chief Edmond Caja, who personally puts me on the kitchen bench, where the result is 47 kg. Unemployment would relieve my body aches from the hard work, but soon two hours of forced reading, staying outside all day in the sun and snow, and the meager and very bad food, would become the equivalent of the wagons, accompanied by the pressure of the police, led by the chief, at every step. The austerity measures had made serving the sentence in the Qaf-Bar prison extremely difficult, where the convicts were strained beyond the limit of patience! Memorie.al