By Ahmet Bushati

Part fifty-four

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Those who were released that day left their comrades in the camp mostly their shoes or boots, and when they had them in good condition, they took any scraps they could find along the way. It was funny to see how the shoes and boots, first of all, flew over the barbed wire, and also, from the inside out, the oldest ones.

During the month of December and onwards, the Kavaja camp’s bunkers, most of which were lower than the surrounding terrain, were completely flooded with water and mud, almost spilling onto the floor of those sleeping on the lower floor, so that even within the corridors of some bunkers, they had to wear boots, while those who did not have boots – and that was the majority – wore trousers that extended above the knee, even in winter, and the prisoners had to go in and out of the bunker several times a day.

During those days, Kolë Kurti and I had occupied a corner of the bunker, from where we would observe how, opposite us, a group of villagers from Central Albania, night after night, were returning from work loaded with plants in the form of leaves, which they would collect around the place of work, or even on the way to work. We had seen them, after selecting them, put them in large pots and, after boiling them, eat them with taste.

The poor people believed that with that they had found the opportunity to satisfy their great hunger. Two or three times they had kindly advised us that we should also collect those plants, which, like them, also had a good taste. As soon as four or five days had passed since they had eaten such plants regularly, we would watch with wonder and pain as their heads swelled up like soccer balls. Poisoned in the brain by those plants, they were numb and confused, unconsciously rolling around in idiotic ways, which sometimes made us laugh. A day later, in a group as they were, they were sent to the Durrës hospital.

The scenes of the starving in a camp are numerous, different and everyday, similar or not, and touching. During those days, an ordinary prisoner from Shkodra, from the “Kiras” neighborhood, by the name of R.O., would impress me with his behavior as a man who had fallen a lot. I had once met him in football. Although poor, he had grown up very healthy and strong, like a true diva! As far as I know, he was a cattle herder, on behalf of a butcher. One rainy afternoon, there in the camp, I watched with amazement as the prisoners gathered around him, who was crying like a child.

I was deeply moved by the scene, and I started to approach him, but in the meantime, a prisoner who was leaving explained to me: “That man from Shkodra who is crying has been stabbed to death by a prisoner who he does not know, but who is asking him to give him some of the food that his family has just brought him.” I was not playing catch-up, because at that very moment I saw another ordinary prisoner from Shkodra, touched by the humiliating behavior of a fellow citizen, forcefully pull him out of the crowd and threaten him: “You have no shame! I feel sorry for these others, because I know what to do, you blackface!”

There were times when rainy weather would lock us in the sheds, and I can say that a day like that, especially in the fall, would constantly make me, breaking the harsh routine of other days, return with nostalgia to my world, to the past and the connections I had and still have. It is not strange that a young prisoner, overcome by the melancholy of the day, would, on such a day, bring out from his intimate and secret recesses, as if small treasures that he had carefully kept at the bottom of a bag or suitcase, and whether they were photographs or letters, on such an occasion, he would look at them with longing, as if he had them for the first time, and he would be careful that no one would know of such weaknesses, as unworthy of a prisoner, dedicated to the end to a cause that required only seriousness and determination, but that nevertheless, as part of his dubious life that they were, they should be hidden from others.

Again, in Gosë i Kavajës

The days of the following spring, the year 1952, would find us again in Gosë i Kavajës with a camp. We were in this camp when we heard that other students had been arrested again, which would lead us to believe with pride that the flames of freedom in the Shkodra gymnasium were continuing to burn as brightly as before. We would also be impressed by any letter that would come from these young students, whom we had never met before.

I remember that their letters would be fiery and enthusiastic. Among others, Xhahid Xhaferi would write to me, whom I had never even heard of by name, but whose letter, among other things, would say: “We continue on your path and we believe that the day will not be far off when perhaps we will liberate you by car”.

We had in this camp when one day Dioniz Miçaço, reduced to skin and bones from the fever of several days in a row, to the words of an officer with a post in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, that “You are paying for what you have done”, Dioniz, very revolted, would answer: “I have been suffering for several days, and you see what I have become. Yes, I will suffer even more, and I will die, but I will never beg for honor and mercy from you”.

Ernest Kraja, who was a fairy at the border, when he was trying to enter Albania from Yugoslavia, where he had been on the run since a few years ago, after being sentenced, would bring us to the camp around this time, a song that the Shkodra refugees in Montenegro had dedicated to the martyrs Bardhosh Dani, Mark Caca and Brahim Dërgut, a song that would take its deserved place in the “repertoire” of our songs, a song that, as we would hear later, had continued to be sung for years and years later, in prisons and camps:

“What did the fairies say in the mountains that are mourning?

What did the waves of the sea that are raging against us say?

What are the nightingales in the fields that are not singing?

And the flag in the oil, why is it there? wave(e)?

Come sun(e)ll, don’t look at my food

Wound Rozafa your three sons from Shkodra

II

The shepherd’s voice is echoing longingly,

From the field below, high above Rumi,

He sadly comes and tells us,

That three young sons were killed today at the border.

What did mothers say about their sons, killed?

How can they go on living with their hearts buried?

III

Let Mark, Brahe and Bardhoshi be mourned,

Who, because of their evil deeds, took the road to exile,

Let the house near Tarabosh be set on fire,

Who betrayed them and the people who left them in misery.

Betrayal will die, with the dirty spy,

That brother, for his life, I wanted to gouge out his eyes”.

We were in this camp, when one night a mouse would bother me a lot, getting under my mattress without getting out, and precisely at a single point that fell under my head. Every time it came to me with such force, so many times I would take it, and while I was dead from sleep that I had never opened my eyes, I would hit it hard and hard with my fists that place where the mouse, apparently with persistence, had chosen to lay its young.

The annoying game with the mouse was repeated several times and when I woke up, the light had not yet come out, out of curiosity about the mattress and to my great embarrassment, I would notice seven of my clitorises folded up as a sign of the punches I had given them from above the mattress, whenever their mother-minushë-had come to take them out into the light, one after the other. Only Qamil Nikshiqi, would be that “man”, who, laughing, would free me from that misery, wrapping those seven thousand tiny seeds with a long thing somewhere outside, the color of living flesh.

In Lekaj of Kavajës

After a few more months, when we left the Gosa camp, we would move to the Lekaj camp, also in the Kavajës area. We were in this camp, when some prisoners, in order to escape the hardship of work, had found some plant with poisonous properties, which when they put on the sole of their feet, it swelled up a lot and took on a bright pink color, shining like a mirror. The wrapping of the feet in this case, for the sake of a few days of rest, it would be a real torture for those who would suffer it.

However, the number of prisoners who were entering into such an adventure increased to about fifteen cases and the command had no difficulty in understanding their trick and, not only that, but that command would seek to use that opportunity, through a bad commissar named Hamdi, with the rank of lieutenant, to recruit from among those sick people by means of some compelling statements that would come before them, that is, that they would agree to cooperate with the Security, otherwise, they would be thrown into the dungeons, without treatment and under the accompanying burns of the legs.

One of these “self-sick” would be Maliq Teta, our friend from Krujë, who, from the dungeon where he was isolated, would one day He sent us a note like this: “I haven’t eaten or slept in three days because of the burns on my legs. Hamdiu – the commissioner – says that I won’t be given any treatment and I won’t be released from prison unless I sign a statement. I want your opinion on this, knowing that I will remain until death, that Maliqi you have known so far. So, I want to know, should I sign that statement to save me once and for all, or not?”

In response, we told Maliqi to continue resisting, otherwise Hamdi would not leave them. After this, Maliqi was kept in isolation for several more days without treatment, and after his legs had deteriorated even more, one day they took him out of the dungeon, but he was unable to escape our harassment for his unsuccessful adventure, which, putting its finger on its nose, would answer us laughingly: “The head does, the head suffers.” This same miserable commissar named Hamdi, a few days later would ask our other friend, Thabit Rusi, to sign a declaration of cooperation.

After three days of Thabit being isolated in a dungeon without food, Commissioner Hamdi, having lost his patience, threw two statements with opposite contents before Thabit, speaking to him briefly and in a tone: “Choose and take one or the other”, where according to the first, Thabit committed himself to cooperating with the Security from that moment on, while according to the second, he declared himself a “sworn enemy of the popular government”. Thabit, who would also lose his patience in this case, without delay, signed the second.

When in September 1954, Thabiti would one day complete seven years of his sentence and, waiting to take the road to Shkodra, home, that piece of paper from two years earlier there in the Lekaj camp, – although imposed and with the value of a declaration – would decide that Thabiti would change direction, to spend another six years in exile. This case passed in silence and oblivion, like hundreds and hundreds of others, doesn’t it show once again how precious honor and a good name have been for a political prisoner? And how would this case speak to those who, in conditions and circumstances like Thabiti’s, did not act like him?

The Çengelaj Camp

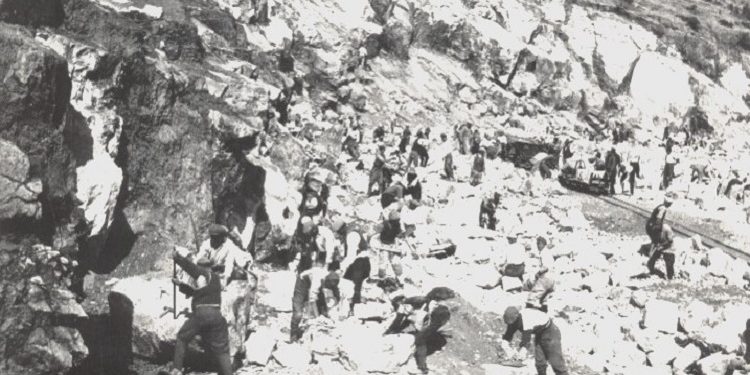

The last camp for us in the area around Peqin and Kavaja would be that of Çengelaj, about seven or eight kilometers beyond Peqin, where they would work on opening a large reservoir, which in the future, the water collected in it, would be thrown for irrigation of the lands in the Peqin-Durrës canal, which we had opened during the last two years, including its smaller canals, scattered all over the field, called according to their size; “secondary” and; “tertiary”.

The conditions in which the prisoners were forced to work, sometimes posed a danger to them, and there were many cases of mutilation and even death, as a result of their poor condition. I once found myself in this Çengelaj camp, close to a life-threatening situation: After some time since the pool in question had been opened, we would dig and level a hill, and transport it by wagon from one side of the pool to the other, crossing its width by means of a narrow bridge made of planks without railings, which was supported on wooden piles driven in with batipal, several meters deep in the thin mud pool.

Over this bridge with rails laid on it, wagons loaded with soil would pass, one after the other, and due to the slope of the bridge as a result of the difference in level between the two banks of the pond, the wagon, under its great weight, would constantly tend to gain momentum and, even to go off the rails, seriously endangering the life of the prisoner on top, if he did not hold the wagon firmly on the brakes throughout the entire “route” over the bridge, by means of a strong ash tree, placed on one of its wheels.

In order not to risk two lives, the guards did not allow two prisoners to accompany the wagon on the bridge, but only one, and they also did not allow a second wagon to enter the bridge, lest the wagon in front of it go beyond the other bank. The eventual risk of being imprisoned in the pond below carried with it his death, because the pond, as we said above, was deep and impossible to swim in, as it was made of thin clay.

So I once came very close to danger and escaped only by chance: Apparently I had driven too fast on the bridge, causing the wagon to gain too much momentum, and although I exerted a lot of force on the wood to slow its speed down a little, it went off the rails and, rolling in the air, finally sank into the depths of the pond. For a moment I was saved, because when the wagon had flown into the pond, I had broken away from it and, crashing against the bridge floor, but when I started back, to my bad luck and contrary to the rule, another wagon, loaded with earth, drove in just as fast, my life was put in question for the second time, within a few moments.

The companion of this wagon, shocked by what he expected to happen to me, shouted and screamed more than he tried to slow down the speed of the wagon, which had gotten out of control. The bridge was so narrow that the upper edges of the wagon could not pass without slightly touching my body, placed on its edge. Miraculously, at the moment when the wagon was passing right near the point where I happened to be, as strong as I was, I was able to, with an “acrobatic” jump, grab the edge of the wagon with my hands and, climbing on it, cross the entire bridge.

There were enough prisoners who had followed the scene with their eyes, who, after being freed from that anxiety, would embrace me with great affection, congratulating me on saving my life. My uncle, who after this event would hug me tightly and be moved, would tell me: “If it happened to you, I would strangle him with the same stick – which he still had in his hand”. My uncle, as a sign of joy, would make us halwa that night.

He had felt Eid

The heel of one of my feet was badly infected, so much so that for several days, I could not touch the ground with it. With a fever and the doctor’s leave, I also suffered the night of Eid, and because of the high fever I had, I could not hear what might have been said about the next day, Eid. It was summer and the next morning, very early, a small window that fell over my head, along with the light that had just begun to dawn, was also letting in a pleasant freshness, which I felt sliding sweetly over my face.

I don’t know what happened that I suddenly got up to look outside, when as if by a miracle, the magnificent scene of the Eid prayer appeared before me, by the Muslim prisoners, who since night had occupied every corner of the entire square of the large courtyard of the camp, which made me immediately stunned with emotion and wonder.

It had felt like Eid! At first, I couldn’t believe my eyes and before I had even regained consciousness, everything there seemed like a dream, as if I were standing in front of a scene that had been left by the night. Imprisoned believers, from the most remote regions of Kosovo in the north, down to those of our suffering Chameria, were rising and falling as if on command, under the deep and touching “call to prayer” of the charming imam, Adem Metalia from Tropoja, causing that communist camp square to be transformed for a short time into a temple, a mosque, where believers suffering from the depths of their souls were praying to the Almighty God, like never before in their lives. It had never happened before!

The word alone, but I, who listened to the hoxha’s call to prayer that spread everywhere, like a call to heaven and the people behind him to obey him so blindly and humbly, did that, as if in ecstasy, it seemed to me that I was somewhere between heaven and earth, between a long-standing childish fantasy, and the reality of a communist camp. Among other things, I would be taken aback and somehow touched by the attitude that those in command were showing on that occasion, towards their conscience, making those people separated from their families and freedom, that day respect their love and connection with God, which was the most sacred thing in their lives.

I had not yet left that small window nor had I recovered from that emotion when I saw how the prisoners, after finishing their prayers, unhurriedly wrapped the mat and handkerchief on which they had rested their knees and heads, and mingled peacefully, praying to each other like brothers and sisters, while I myself, as if I wanted to call out: “Albanian, Albanian, have you ever had a prayer?” and “Do you really think you will one day become one?”

For no more than three months, in the wonderful camp of Berat, not lingering with the usual events of a labor camp, from the dawn of 1952, we left Çengelaj and headed for the camp of Ura Vajgurore, “Lapardha” of Berat, where other prisoners had long been working on the construction of a military airfield. In this “magnificent” camp, we joined two camps and would stay together until the one in Vlashuk, which was our destination, was prepared.

The Ura Vajgurore camp would be remembered as the largest camp that had ever existed, albeit for a short period – with more than four thousand prisoners, as well as the camp where a majority of political prisoners would get to know each other and from where one day, they would leave, having left and received indelible impressions, for a lifetime.

Among others, there we would also meet our friends from Shkodra, who had left the camp after us, such as; Sami Repishti, Xhevat Meta, Ernest Perdoda, Tomë Sheldina, Et’hem Bakalli, Zef Nika, Nush Tuka, as well as Feti Quku and Mark Lleshi, who were going to prison for the second time, etc. We would also find in that camp, friends from other prisons, with whom we had known and connected since two or three years before, among other camps. Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue