By Ahmet Bushati

Part forty-eight

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

John would not let an opportunity pass without taking advantage of it, except to make others laugh. There was, for example, an occasion when John, as he was taking the dish as if it were his turn in the kettle, would notice that in his container, besides the thin liquid, there was only one pepper in it, which for humor, he would take out as if in anger, slam it on the ground once, and then, in front of the others, give the sentence of execution, for the crimes that that pepper had allegedly committed in his bad past, to the surprise of the prisoners around him, after cleaning it a little with his hand, so as after the decision made a little earlier, that pepper, in the most spectacular way, he would finally throw it from the top and, straight into his mouth, open like a sock!

John’s mockery knew no bounds and had no limits. It used to happen that John, supposedly indignant about the empty dishes – dishes that we called “lang spirilangje” – would give a short speech in front of his tray and, in his anger, pretend to spit on it, and sometimes, for more humor, he would actually spit on it, and while some of the prisoners would wait for him to throw the dish on the ground, John, perhaps hungrier than the others due to his large physique, would sit down without making a sound and eat the same dish calmly and with great appetite.

Once we were digging and digging a hill, where we had found a lot of skulls and limbs of dead people, maybe a hundred years ago, and John, who knows how many times he had seen it, would put a few skulls in his mouth and, from a slightly elevated position, would pose majestically in imitation of Dante’s Farinata, uttering a series of big and meaningless words on the occasion.

I would not have believed that the brains that had come out of a man’s skull could be put back into him by hand and, while he was still alive, back into their place, and that after a while he would finally return to his normal state. We heard that this happened one day to Nuh Dyli from Bërdicet, when he was buried under a large mass of earth while he was digging for his bottom.

The mail in this camp was delivered by a certain Xhafer Kondit from Korça, a kind and apparently cultured man. Regarding letters, apart from my family and relatives, Simja would also write to me regularly, while the other friends, with some very, very rare exceptions, out of fear, would not write to me.

As a basic food throughout the history of the camps, there would be only kachamak, – the Shkodra porridge – which we cooked ourselves, food that would keep thousands and thousands of prisoners alive for years and years. Behind it, far behind it, would come the wheat bread we dried in the sun from our families, which, – as we know – as we were deprived of the right to alms, they would buy more expensively, when their financial possibilities were also much lower than those of the rest of the population.

Grosha was considered the best dish, which we could use no more than once or twice a week, especially on Sundays. A few packages of pasta, a little wheat flour, enough for a halwa on rare occasions – especially when food came, or on festive occasions – eggs, a little sugar and marmalade, would be the last items, considered by us “luxuries”, within a package that the family brought us.

Tobacco had special importance for the prisoner, for the one who smoked it, without which he would play mind games. Matches were not allowed, and instead of them we would use the “luck stone” like centuries ago, which consisted of a piece of flint – the only one of whose quality we were masters – the “spark”, which when burned, spread its very pleasant aroma and a piece of bright felicle that would contain the “luck”. Every man who smoked would carry a small bag of cigarettes, a cigarette lighter, in his pocket, hanging from a string on his pants.

The small square in front of the kitchen was considered the center of the camp, which in the evenings was regularly transformed into a “milet bançe” (popular flower garden), where, so to speak, improvised concerts were given by some prisoners of Tirana, such as Qemal Shatku, son of former minister Shefki Shatku, who, for fun, would wear a tall red hat with a tuft at the back, and who would use an empty water canister as a “tambourine” that sounded loudly. Ibrahim Hasnaj, who, it seemed, was a great fan of Tirana kanga, also participated in that choir.

Among others, you would also notice Selim, the Tirana youth who was healthy, kind and handsome and who would melt during the day singing a song with the name of his lover, the memory of whom, – as he himself told us with seriousness and pain – was not separated from him day or night. The “orchestra” in question, in addition to a couple of other drums that deafened the ears, would also have as another instrument a powerful bell which, due to the great discomfort it caused in the ears, surpassed all the drums together. These so-called “concerts” were attended night after night by the prisoners of Tirana in general and, especially, by the ordinary ones.

In the wave of this relatively good and tolerant atmosphere, the good attitude of some of the prison policemen, who in the camp had approached us as the freest to feel them, and to any of them, we would have been open to the end. It was precisely at that time when we were informed that the “Committee of Free Albania” had been formed in emigration, with Mit’hat Frashëri as chairman, the time when we began to believe that Western politics was finally moving in our direction and that, among the many repercussions that it would have, there was also the possibility of our mass escape from the camp.

About this matter, one day I spoke in a very secret and confidential manner, with Sergeant Tofik, Teufik Luzi from the villages of Berat, who had the guards around us under control, during working hours. Sergeant Teufiku agreed, begging me not to discuss the matter with my comrades beforehand, and in advance he showed me the direction we would take in the event of an escape, a direction which he had previously set up on a steep hill, and would cover with machine gun fire, a direction and point which he had shown me on the first day of the conversation. Towards the beginning of June, instead of Tasi Marko, they brought Beqir Baja from Elbasan as our commander, whose good conduct gave the impression that it did not stem from instructions received from above, but from him as a person.

His difference with Tasi, – a former baker in Korça – was also evident in his direct meetings with the prisoners, as he was more sincere and civil. Often after lunch until dark, he would dig himself and with a bulldozer, the yield of which was said to be in favor of the prisoners. This peaceful camp life that had been going on for several months would suddenly be interrupted and changed for the worse, as a result of the escape from the camp of three ordinary prisoners from Mirdita, one of whom was named Frrok, the camp cook, a short and healthy young man who seemed agile and humorous – another named Bardhok, – physically weak and a little tall, as well as a third, their friend.

For more than a week, work was stopped and we were locked in the bunkers, under real terror. We had no right to move at all from our place or even to talk to each other. Ordinary brigadiers and spies armed with thick sticks and always accompanied by the most evil and trustworthy policemen of the command, would circulate without rest, both in one part of the camp and in the other, ready to attack anyone on the slightest pretext. To go to the W.C. during those days, you had to get permission and the way from the bunker to there, you had to run, and it was not said that on any of these mandatory exits, you did not receive a hard blow from a stick on the back, or between the legs. Some of us who did not run for the sake of running were lucky, as we almost did not put ourselves to a difficult test once again.

Terror day and night. Prisoners were beaten without pretext or warning in the appeal line or in front of the cauldron with food, on the bed and everywhere. A few days earlier, Hajdar Rus had also been removed from the camp, after he had beaten the camp’s prisoner commander, Hamdi Lena. Another event that risked maintaining that difficult situation, or making it even worse, would be the one that would have as protagonists Rrok Pali and Xhevat Quku, who continued to be together in the third brigade. And this is how it happened: while Hamdi Lena was standing – as at every lunch – at the head of the cauldron when the food was distributed, a quarrel had broken out between him and Rrok Pali, who was waiting for his turn with a basket in his hand.

Xhevat, whom the policemen who were ready, had tied to a pole as punishment, had joined in supporting Rrok. Rroku, who had thought that Xhevat, exposed to the scorching midday sun, might faint, had run towards him with a water jug in his hand, which had angered the police, who had then untied Xhevat from the gallows and instead hanged Rroku, who, due to his poor health, within a few minutes had started to scream for his life and was finally hanging from the rope unconscious. It was a great fortune for him that at that very moment, Commander Beqir Baja happened to be passing by, whom, although he was not behaving any better with us during those days, would do his best to send Rroku urgently to the Peqin hospital and bring him back to life!

After more than a week of being locked up in the bunkers, one day they took us out to work again. To the harsh climate of the camp must be added the great heat of 1950, for which we had heard that very high temperature levels had been recorded. The day was very long and hot, as was the very high temperature. From the great heat, especially around lunchtime, if we were to look with our eyes at the vibrations of the air, the tiny vibrations of thousands and thousands of waves about a meter or less above the surface of the entire ravine, – the space between two escarpments – closed on the sides by two high escarpments…! At least a couple of times I ran out of the deep ravine, where it seriously seemed to me that I were being suffocated.

Then the thirst for water, a real torture for everyone. The attack that took place during those days around a water canister, which came every two or three hours for more than a hundred people, is indescribable. The struggle for a drop of water, as for existence, would appear to all of us in its most extreme ugliness…! The loud screams that would echo from an uncontrollable crowd of prisoners, who would push each other as if for life or death, and the clashes of measuring cups and other aluminum containers that would be tightly clenched in the energetic and nervous hands of the prisoners, who were, we might say, going crazy for a little water, would be scenes of true hell, and would be repeated several times a day.

It is a fact that it must be affirmed that generally political prisoners and a small number of restrained ordinary people, would face such situations, no matter how difficult, without giving in and with dignity, preferring silence and sacrifice, instead of slipping into the body of life-giving water. On such occasions, who knows how many times in a day, these good and dignified people would follow with contemptuous glances the water jug that always passed them empty. On such occasions, I would notice a bitter smile on their faces, perhaps one of pity or gentle and human revolt, which in any case did not express anger.

It should not be left without mentioning that we young people, seeking to be an example of sacrifice, – as was our duty – has constantly left ourselves for last. So on those days, even if, like the others, we were burned for a drop of water, it happened more than once that the water we secured, even with the help of others, we would distribute it along the way to the older, the more helpless, and return to our friends with empty jugs. I would spend fourteen camps as a prisoner and after so many lives gone by, two jugs of water to drink at different times and camps, just like two jugs of water once in Sigurim, I would never forget them, not even today. The first case belongs to the period we are talking about:

Like many other times, one day I was returning to my friends with an empty jug. Ruzhdi Çoba, who was watching me, broke away from his work and came out to me asking: “Do you drink water?” “No”, I replied. “Wait”, – Ruzhdia told me and ran away to his belongings. From under them he took out a jug of water, which when he held out his hands to me, I was watching him greedily to see how it shone with fresh beads of sweat. Jean Valjean’s “breads” and Migjen’s “forbidden apples” seem like a bunch of nonsense when compared to the encouragement a pitcher of water gives you when you’re thirsty to death.

“Drink,” Ruzhdia said in a tone, as if he wanted to avoid the approach of any other possible person, and I drank as much as was regularly drunk from a mug, which was calculated to moisten the lips of more than three or four other people. As I pulled it from my mouth, Ruzhdia intervened quickly and authoritatively: “Drink, drink”! And while I objected, he would repeat to me even more insistently: “Drink, drink, come quickly because it is your risk”! And then I drank that unforgettable mug of water to the end, properly quenching my thirst for the first time in several days.

During this time, I felt sick with a constant fever and, nevertheless, I was forced to go to work, due to the situation that had developed in the camp those days. We no longer enjoyed the right to a medical examination. I had not eaten for several days and my legs would not support me, while my thirst for water did not leave me day or night. I was convinced that those fevers came to me as a recurrence of the malaria disease, which I had suffered from several years ago. I was able to secure some “aterbrina” and “plasmokine”, which I had once used against that disease, which then made my face no less yellow than it was. My friends, seeing my physical weakness, as well as the yellow color that I had acquired on my face, whispered about me secretly, and I pretended not to remember anything.

The stay in that camp of Ura e Bono did not last long, and one day, when it might have been the beginning of July, we were told to pack up our belongings, that we would be changing camp. The destination? As always, unknown. Our cramped quarters in the cars were a real torture, which would last until we reached our destination. If I remember correctly, they had us packed one on top of the other, sixty prisoners, for each Zis car, which would mean double its normal capacity. We were so packed on all sides that there was absolutely no possibility of moving an elbow or a knee, which were stuck as if by nails.

We would dream of being in a heap, with our elbows pressed into our comrades’ ribs and our knees raised high above our chests. Only the policemen’s batons, which without any pretext fell on the heads of one prisoner and another, could keep that unbearable situation under control. And as always, there is room for laughter, in this difficult case, I could not help but laugh when I saw how a policeman named Ferit was beating with a stick the shaved heads of two of my friends, Hilmi Kamata and Ahmet Koplik, who had been saved the day before.

After about thirty kilometers of travel, we finally arrived at the place called Beden, where from the beginning I was struck by its bare and gloomy landscape, where that infamous camp was being set up for the second time, from which not everyone would be lucky enough to leave alive.

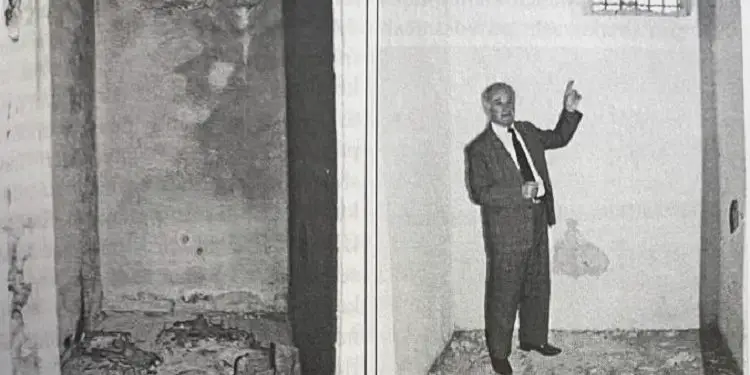

The Beden Camp of 1950

The change in treatment of one prison camp from that of another, for the same period, would not constitute an anomaly at all for a communist regime and for a Ministry of Internal Affairs headed by a criminal and capricious man, such as Mehmet Shehu. The Beden Camp of 1950, as a camp of savage terror and great physical hardship, would have all the characteristics of a communist extermination camp and would not differ in any way from the one with the same name of two years earlier, except for the fact that in this second camp the prisoners would be allowed to have food brought to them by their families, something that had been forbidden in the one of the previous two years.

The prisoners, as before, were divided into small work groups of two or four people and were forced to dig the norm of four cubic meters of very hard soil per person into the depth of the canal – which had been left unfilled by the prisoners of the previous two years – and then, with an old cart, they were supposed to finally pull it out of the canal with the help of a high escarpment.

This norm, which was normally unachievable, would not have been achieved by any of the prisoners, unless the policeman’s baton fell on him, unless his bread ration for that day was taken away and in that case, even if he did not lose face in front of everyone. Such a large norm would be achieved only by working throughout a long summer day, without ever slowing down the pace of work, despite the scorching rays of the sun and the great thirst for water.

Those who would not achieve the norm, their bread for that day was cut off and around midnight, accompanied by a policeman, they would appear at the command to give an account to the most dangerous and sadistic, Lieutenant Ademi, from the villages of Gjinokastra, and this, after the prisoner had waited an hour or two in line outside, under the supervision of a policeman.

Since, as per the instructions, the treatment of the prisoners would get even worse, the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tirana replaced two of the former key command cadres, thus Commander Beqir Baja was replaced by Beqir Liçi, also with the rank of major, who a year earlier had been commander in the Orman-Pojani camp, a commander who among us called “Napoleon”, both for his arrogance and for the authoritarian distance he maintained from all his subordinates; and instead of the previous commissar, they would bring Lieutenant Adem there, a man who, in terms of wickedness, would surpass all those we had had up until then and who we would have in the future. Even when one day the prisoners were skin and bones left, he would boast with a criminal during a meeting with the prisoners: “We will only leave you your lungs”!

Along with the two above-mentioned cadres, they also brought the prisoner Vango Mitrojorgji, a former high-ranking official in the Ministry of Internal Affairs during the time of Koçi Xoxe, who, despite the great zeal he had shown during his criminal work, Enver Hoxha would condemn together with Koçi Xoxe, in order to justify before the people the crimes committed by him and the party he led until then. Vango Mitrojorgji, for his part, had brought with him the arrogance of a former militant communist and the cunning of a former important cadre of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which was also shown by his face and behavior. In that camp he would be treated with all the possible favors and honors of a former high-ranking and trustworthy cadre, respected by the command. Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue