By Ahmet Bushati

Part forty-six

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

In that room, together with us, there would also be two former soldiers of the People’s Defense named Remzi and Njazi, where the first probably had the surname Hasanllari, both from Devolli, who had been in prison as implicated with the prisoners of the Postrriba events, that is, for the help they had given them. They were very educated, and as it were, they saw themselves constantly surrounded by the gratitude of everyone, for the sacrifice they had made for the benefit of the prisoners of Shkodra, which is why I also took a little space in this work. A group of our friends, having been in a brigade with one of them, Remzi, would have him as a member of the sofre for a long time.

Maliq Teta from Kruje, would be one of those good and brave boys, who had been arrested when he had tried to escape. Maliqi was known to several families of prisoners from Shkodra, since he, as a former member of the People’s Protection, had served at a prison here in Shkodra, openly helping the families of prisoners, as well as the prisoners themselves. For a long time in the camp, he would also be a member of our table. No one would escape the prison’s yoke, not even the priests and imams when the occasion arose, although they, both from their attire and from the attitude they maintained, would constantly enjoy the respect of everyone.

Ali Brahja from Tropoja learned Italian from Father Donat Kurti. They often sat next to each other, and it seems that they had become friends over the long time they spent together. Ali Brahja was a good man, kind and gentle, but it was not uncommon for him to sometimes mock – albeit in moderation – even his own people, without sparing, at least once, not even Father Donati. So when once during a lesson, Ali wanted to pronounce the word “fanciullo”, at a time when by coincidence his eyes met our smile that we were observing as if by chance from a close distance, he immediately, disloyally mocking Father Donati, his friend and teacher, for humor, would take the pose of a fat fool, pretending to have great difficulty pronouncing that simple word.

So, several times in a row, as if he were mute, he would repeat the syllable “fan-fan, fan-tan”, seemingly unable to pronounce the two syllables in succession, until once, as if freeing himself from the first syllable, he would confidently and forcefully pronounce only the word “kulo”, with a load of banality, as had been his intention, while Father Donati, for his part, scandalized that someone nearby had heard him, lowering his eyelids within his crotch, would correct Ali in his low voice:

“No, no, Ali, fanciullo, fanciullo”, – and Alia behind him, without mercy a smile as cunning as it was kind, would finally pronounce that word as he wanted. If it were not necessary to prolong the endless gallery of prisoners in a prison cell, I would like to close its tableau with a former spy, and precisely with Lazar Anastasi, who, repenting one day for his deed to the detriment of his fellow sufferers, would return for good, declaring himself with his sincere “mea culp”.

Lazar Anastasi had deserted from the National Liberation Party in 1944 and joined the forces opposing it, and he said that he had also collaborated with the Germans. It was said that, like a certain Tuçi Lenet, and two or three others, he had also served the prison administration as a spy for some time, and then gave up. We regretted the above, one day he would approach a group of us, begging us to believe that he was very sorry for the position he had held until some time ago and that, in order to convince us to the end, he was ready to put us through any test, no matter how difficult it might be.

Regarding his request to “confess”, we recommended one of the older men, and he immediately asked for our consent for the name of Xhevat Dani, which we supported, having a gasp and almost bursting at our eyes. Lazar had preferred Xhevat, since he knew his gentleness and tolerance. While Lazarus was confessing his past “sins” to Xhevat Dani in one corner of the room, we in the other corner, completely opposite, were gasping for breath watching the scene.

Although we continued to have reservations about Lazar, like the worn-out spy he had been, the truth was that Lazar, even though he had turned once and for all, continued to experience with difficulty a permanent pang of guilt, as long as his “good attitude” had not received our sincere affirmation. Especially during his stay in the difficult Bedeni camp, he had several times and deliberately opposed the police and one day they, in the eyes of everyone, would torture him a lot, – perhaps even as he himself dishonored it – and after successfully passing that difficult test in front of many prisoners, he would immediately come to me and say: “Hey Ahmet, are you now convinced of me”?

Lazar sang beautifully with a light and quite melodious voice. Like no other, with the most melancholic notes, he would sing especially the sad Albanian song, “O beautiful More, since you left me, I have never seen you again”! Upon his release from prison, he had escaped to Yugoslavia, and I am not sure if he, as we had heard, had ever entered Albanian territory to carry out an armed action.

I had made it a habit that even after the others had gone to sleep, I would either continue talking to one of the two prisoners I had in my arms, or I would read a book I had in my hand. I remember that on one of those nights, I was finishing reading the book “Polar Explorations”, the impressions of which and the names of those great heroes, such as Amundsen, Nansen, de Nobile and Pearl, – who was the first to plant the American flag at the North Pole – would never be erased from my memory. It was precisely on one of those nights, at a time when the silence of the night and of the prison was deeper than ever and the prisoners had been asleep for an hour or two, that a loud noise would suddenly resound in and outside the room, and would wake up all its prisoners with a start. At that moment, the two policemen on duty would come running from below.

The prisoner he had summoned was a good man and respected by everyone, but under the emotional effect of a special meeting he had had with his wife that day, he had lost his mind for a few moments and spoke in a foreign language, as if in a daze, some unusual words, with which he would shock all the prisoners in the room, even though most of them did not understand that language, which was not even Italian. It would not take more than a few seconds for him, with his head raised and leaning on one elbow, and with a stern look and tone, and always with an even fuller and clearer voice, to address the room for the second time: “Do you want me to tell you in Albanian?”

He translated into Albanian what he had said a little while ago, and then he sank like a dead man into the mattress, so as not to be heard any more, and after him, the room, touched by his desperate state, would fall asleep with the silence imposed on it by the shock of their honored fellow sufferer. At every dinner, there would be a meal that would greatly enliven the room, and precisely at that time when the policeman’s whistle signaled for dinner and going out for a need, this time when the whole room would suddenly be involved in a hasty conclusion to the conversations that had been going on, as well as energetic and often humorous comments about the fate of games, such as chess, backgammon or dominoes, even those that were unfinished.

It was more or less this “meal” in the evenings, when I was walking somewhere in the depths of the room, I would notice that a prisoner, whose face was not yet recognizable, entered with some belongings in front of his hands, which he quickly dropped under his feet, and in the meantime, the prisoners sitting near the entrance, suddenly got up to speak to him, and also behind them, several others, who apparently recognized him, rushed towards him quickly. Out of curiosity, I also took two or three steps forward, but not knowing who the man was, I stopped again. Not even a minute had passed when that young prisoner himself, to whom our eyes had converged in a room, saw and recognized me, and with hands outstretched in front of him, he started towards me, calling me by name and surname.

I also recognized him then: it was Ruzhdi Rroji, who a day or two earlier had been spared his life, after several months of being sentenced to death in a Gestapo prison. Before I could even get close enough to hug him, he would tell me in a raised voice: “… I have followed your sufferings with tears.” There is no more despairing moment for a prisoner than when he feels forgotten by the society he has left behind. A letter that comes to you in prison from a friend will seem to you as if it had brought with it the echo of your calls, proof of solidarity with you and appreciation of your sacrifice. “Do not forget the prisoners,” a Russian revolutionary prisoner would write, having experienced for him the great need that the prisoners have for solidarity and support.

The idea that you continue to live in the minds and hearts of all those you have loved and known keeps you morally high when you are imprisoned, and it is quite the opposite when you feel abandoned by society, not even by home, when even a day in prison would be life for you. In addition, prison is also that place that makes everything that until then you may have kept hidden in the depths of your soul come to the surface. In prison, there is no shame in showing your feelings to your closest ones, for the need to relive them. But when you are twenty years old, and suddenly receive the first letter from a friend of yours, from whom prison has separated you for almost two years, on the verge of a great love, is it not the case that you experience a joy and a longing that cannot be described in words?

That’s what happened to me on the evening of December 24, 1949, when Sergeant Teufiku brought me a letter by hand from Sime, my beloved and brave friend, who, like Gjylter, the sister before her, would be worth more than a man. Sime’s letter – the name with which I would associate the most beautiful dreams of life over the years – I read quickly and quietly, secretly from everyone, and with the pleasure of reading it again later, I put it under my pillow, just as one puts a treasure that no one wants to know about. Ernest Përdoda, with whom I slept head to head, I could not bear not to tell him, and yet, out of impatience to read the letter again as soon as possible, I was waiting for Ernest to fall asleep as soon as possible, which was not happening to him, not even after the last bells of the Christmas Eve night had rung, which the prison and the late hour of the night made him even deeper and more melancholy than usual.

It was the holiday itself that, it seems, had made him long for sleep. In fact, I also felt longing when I heard that sound of the bells, which I had learned to listen to since I was little, which I also told Ernest. We would continue to love life as we had found it, with the “adhans” (calls to prayer) of the high-pitched hoxhas, and with the ringing of church bells, with Eid celebrations, and Easters with red eggs and carnivals. Once Ernest fell asleep and I took out the letter to reread it once or twice more. “You who are my dear and unforgettable friend, whom I constantly remember”, etc., etc., would be the wonderful words of that first letter, which would fill my soul with special love and joy.

As a time of intense feelings that it was, I can say that the day I crossed the threshold of prison, I felt Sima inside me more than ever before. During a year and a half in the Security Service, under investigation and with inextricable torture, as well as when death was so close, Sima would be with me. I would have her with me throughout my other prison lives, having her as my second self. The spiritual connection with her would be that wonderful idyll that would constantly fill me with the most beautiful poetic inspiration and would be an additional motive and strength on my path inspired by high ideals.

Abdullah Nela

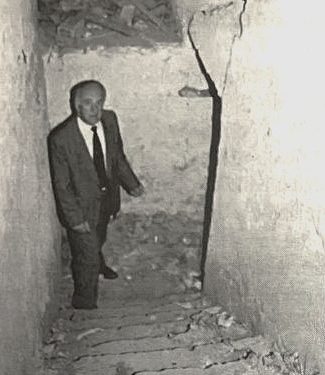

The Great Prison of Shkodra was a two-story rectangular building that enclosed within itself, like a void, a small courtyard with a concrete layer, called the inner courtyard of the prison, in the center of which there was a well that gave us water to drink and wash. The other courtyard, the larger one, where we were taken out for airing, extended on the other side of the prison building and parallel to the road that came from “Parruca” to the Municipality. The prison had ten rooms, four of which were large, namely those with numbers 1, 4, 7 and 9.

On both sides of the rectangular building with a courtyard in the middle, there was a staircase leading down from the upper floor and under each of these two staircases, a pair of small dungeons about 1.5 x 1.5 m, with a very small window in the door, which was usually kept closed and which served for ventilation and very little light. In these dungeons, prisoners were isolated for violating prison rules, but they also served as “transit” points for prisoners and the dead, before they could be taken to their families.

One day we learned that in one of the dungeons opposite us, they had brought a young man sentenced to death. Later that day, we would hear that he was sentenced to death, he was from Luma, and that his name was Abdullah. By dinner that day we would learn that the boy had served in the army with the rank of captain and that he had been sentenced by a military court. The roommates of the man sentenced to death, speaking to us with pain and sympathy for him, would tell us that when the police took him out to the W.C., constantly escorted by them as if he were sentenced to death, they had seen him always walk past with his head held high and smiling. Even though we didn’t know each other, we became spiritually connected to him and the idea that he could shoot us from one day to the next added to our pain for him.

Since we didn’t have a room where the dungeon with Abdullah was inside was, we couldn’t pass by him near that dungeon, but after hearing that he was always standing behind its door, we would greet him whenever we went to the W.C. as a sign of encouragement, looking in his direction with a smile, and when the guard didn’t happen to be there, even shaking his fist forcefully, and in all cases we would receive from him in response a smile that we would understand from a pair of regular, white teeth, which would immediately appear in the small window.

As after the signal that the police had taken to the prison directorate that; “Some prisoners were not greeting the prisoner sentenced to death”, the director, for her part, would order that Abdullah be transferred to one of the two dungeons on our side. Since the first night, I and Maliq Teta, were able to find a room in whose courtyard there was a crowd, who gave us water to drink and wash. The other, large courtyard, where we were taken out for airing, was on the other side of the prison building, parallel to the road that came from “Parruca”, to the Municipality. The prison had ten rooms, four of which were large, namely those with numbers 1, 4, 7 and 9.

On the first night, I and Maliq Teta were able to, in great secrecy, remove a brick from the wall of the back of the dungeon, the wall behind which our ladder descended from room 9, and then, so as not to be noticed by the guards, we would put the removed brick back in its place, so that it would not be noticed by the guards. From that night, Maliq and I would communicate with Abdulla Nela. The next morning, from the little light that entered his dungeon through the old door of the hole that we had opened, we would notice for the first time that Abdullahi was a young and very charming boy, tall, smiling, who spoke fluently and who, above all, manifested great courage. They connected with the hole he opened in the wall, we informed some of our friends, who would then go down one after the other to meet him, and when they returned, they would say something like this: “Look what a boy he was! May his life be spared?”

At the end of the next five or six days, Abdullah’s life would be spared, and from then on and on, Abdulla Nela would be one of our inseparable friends, always brave and ready for any sacrifice. Even when after many years he completed his sentence, he would not allow them to go home, but would exile them for years.

Suddenly we leave for the camp

The days, calm and with their usual rhythm, continued to roll one after the other, until suddenly, on the morning of January 18, 1950, we were informed by the directorate that “whoever comes up with a name, should get ready with all their belongings.” The word was to leave for the camp, although it was still winter. It had not happened and it was not even thought of going to the camp in winter conditions. The news fell like a bomb, especially for those who had not yet turned two months old, since the time of Orman Pojan’s return from the camp.

The camps were a difficult ordeal for the prisoners; they would have been even more difficult for their families, due to the numerous and sometimes unbearable problems they had to face in such cases. And the truth is that most of the families of the prisoners did not leave any sacrifices undone, in order to secure food, and even some loot, and with them on their backs, to follow their people wherever they wanted, regardless of the country, just to keep their loved ones alive. Those were very difficult times, with an economic crisis for everyone, but for families with people in prison, it was several times more difficult, since they would be excluded from the right to have a little food and clothing like others, being forced to buy even their daily bread in special bakeries at an expensive price, while the opportunities to earn a living were blocked from all sides by the government.

The news that we would be released to the camp suddenly changed the atmosphere of the prison, introducing a lot of preoccupation among the prisoners, and as usual, also sadness. All those who heard that the duel had taken place began to quickly gather their belongings, in order to have enough time to part with the comrades who would be left in prison. I also wrapped up my belongings and, as if to console my family on this occasion, I set about writing a letter: I sharpened a pencil and on the windowsill I began to write finely on some thin sheets of parchment, where, among other things, I begged my men to be patient and to stay strong. For the purpose of encouragement, I told them once again that they should feel happy that I had come out of the Sigurimi alive. These thin sheets, rolled up in the shape of a pencil, I inserted into the hole through which the elastic of my pants had passed and together with some other unstained clothes, I left them with a friend to send home for me.

I first copied the method of inserting a piece of paper through the elastic of my pants from the practice of a friend of ours, who had constantly fed us political news, sometimes received from the people and sometimes heard on foreign radios. Our older friends had described the camp to us in all its dark reality, with its hunger and hardship, but nevertheless, some of us saw going out into the camp as a necessity to stop being closed off as before and as an opportunity to get to know other prisoners.

After the reading of the names of those who would be sent to the camp was completed room by room, and after these, as they had experienced, had organized their belongings into bundles beforehand, the entire prison, taking advantage of the freedom that in such cases was given without reservation by the directorate, was engulfed in a very rapid movement. Excluding the elderly and the sick, among who were also young prisoners who had provided a medical report, all the others were preparing for the camp. The separation of the prisoners from each other had its own peculiarities. They were separated from their friends and comrades, who had greatly eased the burden of prison for each other, by the fact that they had been together, and they were also separated from their brother who had come from the same mother’s womb. The separation would be quite painful.

The prisoners who remained in prison remained silent and weak, while those who were leaving remained strong and asked to be encouraged by their predecessors. “Farewell, “Stay healthy”!” would be the greeting that would be sent to the man who was leaving prison, while the latter, sometimes with tears on his face, would reply: “Come back healthy”! Not a beehive was boiling with so much excitement, as our prison was boiling that day. Or wasn’t there also quite a commotion on that occasion, both from the numerous movements of the prisoners, and from the various messages that they left, – often loudly – to their comrades who remained in prison! The prisoners were escorted to the camp by their comrades, like soldiers to war. Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue