By Ermira Isufaj

Memorie.al / A girl who loved freedom so much that she preferred to sign her poems and stories “Colombia-Pëllumbesha”, never thought that her freedom would be violated! Born into a wealthy family in Gjirokastra, where culture and education were undoubtedly considered “dowry”, childhood friend and pen pal with Musine Kokalari, Selfixhe Ciu could not be one of those girls who stay behind the scenes. The newspapers “Drita”, “Populli”, the magazine “Bota e Re”, “Diana” etc., would become the stage for her ideas, in the mid-1930s. The fascist occupation of Albania that she would find while studying in Italy, in Florence, would significantly influence her ideas.

Although she could have chosen to live a quiet life, away from the hustle and bustle, why not in the Florence of art, Selfixheja, together with her husband, Xhemal, returned to occupied Albania, settled in Shkodra and opened a bookstore, which they called “Shkëndija”. Very soon they would become among the first 200 members of the Communist Party. And perhaps this is where the ordeal of the Broja couple’s life would begin. As one of the organizers of the demonstration of February 22, 1942 in Shkodra, she would be arrested, while her husband would go underground. The Prime Minister of the time, Mustafa Kruja, had imposed the death penalty for the girl from Gjirokastra, but fate would have it that she would be released from prison very soon.

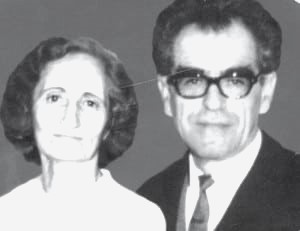

Meanwhile, she had lost some of her best friends, Qemal Stafa, Vasil Shanto…! And if every effort she made were multiplied by zero, the new communist government would treat Selfixhe just as harshly. Since 1947, her family would be exiled twice, first to Kurvelesh and then to Gradishte in Lushnje, and also undergo rehabilitation. After the first rehabilitation, her husband, Xhemali, educated in France, would be one of the founders of the People’s Theater, which he would direct for almost two decades. Selfixhe Ciu Broja, with a skillful journalistic style, has left all of this as evidence in the book “The Waves of Life”.

Imprisonment, association with Musine Kokalari, Drita Kosturi, Qemal Stafa, Vasil Shanto…, expulsion from the party, internment, and letters sent to former war comrade Nexhmije Hoxha, who never replied, then to Mehmet Shehu, and many painful memories, come through this book of memoirs, today that Selfixhe Ciu Broja is no longer alive.

Memories of Selfixhe Ciu Broja

Torture in Tirana prison and Vasil Shanto’s unexpected visit

Arrested during the anti-government demonstration in Shkodër, after isolation in a cell and in prison, as well as ten days in the hospital, in the surgery ward, the investigation transferred me to the Military Court of Tirana prison. Being in critical condition, as a result of the beatings at the demonstration of February 22, 1942 and the inhuman treatment at the police station, my father, with special permission from the Director General of Police, Zef Kadareja, hired a car where, accompanied by an Italian marshal and an Albanian carabinieri, he escorted me to Tirana. The road from the Prison Directorate to the women’s section was short.

The guard, who performed this job like any other, when she found herself in front of the iron gate, took the keys tied to a thick chain from her pocket and opened it with a feeling as if she were opening the door of a house, to an ordinary visitor. As if stuck on the threshold of the door, I could not free myself from the impression of that ghastly creaking that the turning of the key in the lock caused, so much so that I felt as if that turning was eroding me like a millstone. Suddenly, I lost my senses, unable to hold on to the door handle, I lost my balance and fell almost unconscious. When I was mentioned, I looked around, aware of my surroundings; a woman came up to me, grabbed my arm and pulled me behind her.

– You don’t have to be so easy, my great lady, leave your noses and lice at home, because they don’t belong here. Here, lice and worms will become your friends, because you too, like me, will be punished with a hundred and one years. Your nobility is of no use to you. And, untying the collar of that rag that wrapped him, he brought before my eyes the row of lice that were blackening on that suspicious whiteness. In that terrible cave, the darkness, the humidity and the smell of excrement seemed to take my breath away. Meanwhile, rats as big as a cat were circling around me, and I had no way to escape them. When they took me out of there, accustomed to the darkness, the light’s radiance stung my eyes so much that I was forced to walk with my eyes closed.

In the cell next to mine was Naim Gjylbegu (one of the five Heroes of Vigu), who from time to time gave me a signal on the wall. He was seriously accused, and he was transferred to the Military Court in Tirana Prison, together with four other friends, on the same day as me. In prison, among unknown prisoners, I suddenly came across my war comrade, Makbule Haxhihasani, the wife of Hulusi Spahisa, because of whom she was paying the penalty, both during the time of the satrap, and now. Even their baby paid the price, as a result of the circumstances created…!

One day, the guard opened the gate and called: Selfixheja in a meeting! And I immediately found myself there. But the appearance of that visitor with a mountainous appearance surprised me. “Who was it?! Right there, under the reflection of his bright eyes, I recognized my precious friend, Vasil Shanto. As we greeted each other longingly, knowing his circumstances as an illegal, wanted and persistently pursued by the fascist forces, I could not help but warn him about this dangerous courage, which could cost him his life. But Vasil, calm and without sharing his smile, told me that it was not the first time he had challenged the fascists. Meanwhile, after the time of leave expired, Vasil handed us a large basket with several types of fruit and said goodbye to us, with that special expression of love, hope and encouragement more than words.

The capital punishment by Mustafa Kruja and the friendship with Musine and Drita Kosturin

The work of the friends there in prison extended in several directions. Radhazi, my close friend since childhood and during the time of letters, Musine Kokalari, imbued with patriotic social-democratic point of view, when she came to visit me, legally and illegally, she would not fail to bring me books according to the orders I made, which were also put to use by any interested friend. Regarding Musine’s visit, I cannot fail to mention her state of mind when she happened to notice the young women filling the prison yard, an indescribable enthusiasm. On this given occasion, Musine’s eyes were blazing with joy. During my stay in prison, I was informed that Prime Minister Mustafa Kruja insisted on giving me an exemplary sentence, as he had expressed to the family doctor, H. Haxhi, in the event of his intervention.

– You tell me to open the prison doors for all the prisoners, but not for her, no.

– After all, she is only a woman, and moreover, a sick one…, the doctor had told her.

– You say she is only a woman, but she is the embodiment of the rebel! I regret not responding positively to your request, but considering that underestimating our opponents has harmed us quite a bit! Take an interest in being well informed about their work, their struggle, their stance in the face of torture, in the investigation, in court, or in prison, even in front of the gallows.

– I am a doctor and a close friend of her family, as much as I am of yours. But I must admit that since she was a child, when she was sick, I have treated the woman in question as if she were my own daughter. Since you are a parent yourself, I would ask you to find a lighter punishment option, such as internment in a village.

– Your protégé, – he emphasized, with a devilish grin; we will send her to a concentration camp. And, rest assured, this measure of relief is dedicated to you, since I had done her an exemplary punishment.

In the prison we organized a course for nurses, led by the medical student, Drita Kosturit, and another course against illiteracy, led by me. On the other hand, with instructions from above, a course was created, where Yugoslav friends could learn Albanian and Albanians Serbian. But this initiative did not yield positive results. In parallel, we took over the processing of wool for the needs of the partisans or prisoners, such as spinning and knitting, etc. We also engaged them to wash and mend the clothes of our imprisoned comrades, whose families were far away.

In February 1943, the warden brought the letter for my release. In fact, my parents had informed me that my release was now a matter of days, especially after the forensic report. On the outskirts of Tirana, they escorted me to a well-known base to spend the night, while the next evening, a friend in charge of the party, took me to a safer base. There I met Gogo Nushi and, as we decided to go to Shkodra, where there was a need for a prepared friend, we agreed that I would leave after a week.

Disguised in the toilette and dress of a fashionable lady, I took a seat next to a haughty major, to remove any shadow of doubt from those present. Thirsty for the people, for man, for the companion of life who, merged in each other, would work for the realization of the dreams of true freedom, of humanism. With this melody of the soul I greeted Shkodra and the future that awaited us.

Expulsion from the ranks of the Communist Party

It was March 23, 1946. I worked in the Education-Propaganda Directorate at the Ministry of Agriculture. We were informed that an extraordinary party meeting would be held that evening, with a delegate from the Central Committee. When the delegate began to read the circular, everyone held their breath. The gazes of those present were fixed on me. Selfixhe Broja with the accusations: ambitious, hates the leaders’ friends, belongs to the bourgeoisie, is affected by the uncle’s case, inactive. All the accusations hit like a hammer in my consciousness. The consequences were known later…!

The first internment and the letter to Nexhmije Hoxha

It was January 15, 1947. The Security Forces had surrounded the house and through the neighbors’ walls they broke down the gate and climbed the stairs, making a noise with their boots and the clanking of weapons. I also had a daughter, Sashenka, with whom we shared the suffering and difficulties of that journey to the internment camp in Kurvelesh. My husband’s parents also found us there, who came two weeks after our arrival.

Old, shaken by this severe and unexpected blow, still not erased from their memory the persecution of their family during the liberation war, rushed from one instance to another to be granted permission to meet us, exhausted from the long and difficult journey, they were barely able to stand. After our entreaty, they had tried to meet our former comrade, Tuk Jakova, a weighty authority, to find out the reason for this latest measure, which had been taken against us and our position in general. He had replied that, apart from the measure as “anti-party elements”, he knew nothing else about the motivation for the internment. And somewhat gloomy, in a confidential manner he had expressed: “In my opinion, the case of their internment in that wasteland will favor them in escaping some irreparable measure”.

After this response, with the loss of confidence in pursuing the matter through legal channels, both Xhemal’s parents and my family members were of the opinion to turn to my former friend, Nexhmije Hoxha, with whom we had also created family intimacy through years of revolutionary activity. No matter how incompatible we were with this proposal, their desperate insistence broke us. We delivered the letter, in which we asked her to let us know the motivation of the mass. But the dictator’s wife-collaborator, transformed into a shadow, did not bother to answer us. She even hesitated to receive the letter. The days in exile were spent amidst suffering and daily work of the side. But, after the breakdown of relations with Yugoslavia, our innocence was recognized.

Haxhi Lleshi’s Revenge

About three months after the noisy party congress, we were summoned to Tirana. We were employed in the arts and culture sector. The atmosphere created after that congress, where sectarianism, a priority of the Security organs, and mainly politics in relations with Yugoslavia were attacked, raised hopes, leading us to a good turn. Meanwhile, in that so-called “rehabilitation”, our relations with the party were still unresolved. Although we did not make any concessions in this regard, Xhemal was forced to approve party membership under the most absurd conditions. A more precise tactic was followed with me. Summoned to the revisionism commission, Haxhi Lleshi, who chaired it, communicated to me: “Your issue regarding party membership will remain open until the party forms a conviction for your position. Meanwhile, you must not lose faith in the party, which will not hesitate to give you a hand. Do you have anything to say?”

Since I have applied for membership, I do not conceive of confronting this commission. However, to answer your question, I can only say this: “If the party has not had enough of the trials of fire of my revolutionary path of several years, it would be a waste of time to seek this conviction in today’s conditions. Thank you!” Turning my back on that formal Commission, through internal monologue I convincingly determined that the change in our position was superficial and that in general the spirit of rehabilitation was simply a camouflage maneuver for dictatorial continuity.

The Second Internment and the Letter to Mehmet Shehu

On the afternoon of December 14, 1966, activists from the neighborhood block informed us that a special meeting would be held in our block the next day and that we must definitely attend. Since there were whispers of indignation in the intellectual environment about this event in general and about the two of us in particular, both for our reputation as frontline fighters for liberation from the occupier, for our consideration as people with sound moral and civic principles, as well as for our contribution as writers and our commitment to the progress of the arts and culture sector in general, to camouflage the unforeseen bluff, two or three days before the event, at a provoked conference with intellectuals, the envoy of the Central Committee, Manush Muftiu, among other problems about the event in question, expressed himself in this way: “If Xhemal Broja wanted to follow his wife, we are not to blame”!

This statement by a first-hand personality could not fail to gain ground in that environment, but also in wider dissemination. They gave us the security measure again, interning us for five years in Gradishte in Lushnja. At the end of the five-year measure of internment, while we were waiting for our release, we were informed of the repetition of the second five-year term. This communication shocked us beyond measure due to our frustration. Instead of praying in accordance with the established rules, we addressed a letter of genuine protest to the Minister of the Interior, Mehmet Shehu. Let it go wherever it may! Without a shred of hope of benefit, to our surprise, after two weeks we were informed of our release, with the right to return to Tirana.

The plans we had made with Qemal, before he was killed

On May 5, 1942, while I was lost in a meditative state, I heard gunshots and, for you, in the space beyond the window I noticed unusual patrol movements. “Was there any escape of comrades from those who were hospitalized, or had some action been carried out?”, I thought anxiously. Meanwhile, the marshal of the area appeared at the door and, as he exchanged a conversation with the guard, with an expression of satisfaction, both of them fixed their gaze on me.

– “A communist of the greats took the trouble for us. Well-informed, our forces surrounded the apartment where he was in the company of a friend and three gentle women… after all, they too must contribute to the victory of communism”, – he said, not without an insinuating smile. Although interested in being informed more precisely, revolted by that derogatory expression towards my friends and the communist ideal itself, I turned my head the other way, to no longer take into account that face of a gullible caped crook into account. But, he, extremely enthusiastic, continued:

– “One of them found a path and, in the confusion, he escaped on foot, the women surrendered, while the communist named Xhemal, after a fierce struggle with our forces, was killed. They have just brought him to the morgue. And he was quite young, a student, but in the party he represented a high position, as they say”.

In the course of his story, the emphasis on the name Xhemal, in reality Qemal, linking that name with that of my husband, struck me as if by lightning, and I thought about it…! After a moment of clarity, it became clear to me that the fallen comrade must have been Qemal Stafa, my closest friend and collaborator and my husband. We had worked and studied together in the country and abroad, many times we had shared a bite and even a bed with him. I admired him alive. Smart, talented, a dedicated scholar, as passionate, manly and unyielding as a revolutionary, as sensitive, loving and compassionate with his comrades.

And now this complete, sublime existence had been sacrificed for freedom, for the people and the homeland. He was no longer alive! I remembered a moment of such euphoria when Qemal presented the plan of the functions that we would exercise, after completing our studies. My husband and Qemal followed the same profile. And he said with a smile: “To be independent, we will open a joint law firm, and we will assign Selfixhe as secretary. The legal proceedings that we will undertake will be for the protection of workers and peasants in conflict with the bosses. Let’s do a recitation test.” Memorie.al