By Ahmet Bushati

Part twenty-eight

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

Farewell to home and school!

January 20, 1948

I woke up that day as usual at the appointed time, and as every day I got ready for school, without showing any concern to the people of the house. With my bag in my hand, there at the top of the stairs, I instinctively felt like stopping and observing the space around me once more, where other roofs, deformed under the weight of the many seasons that had passed, seemed to me to be weeping sleepily and sadly, while on that rainy day, as if following a monotonous rhythm and a languid sound, they were releasing their little sufferings under the stress on the cobblestones. Further, as always, the majestic crest of our “Chinar”, would slowly sway from a mixed wind that blew without stopping.

Fine raindrops, as if made of gray dust, swirled in confusion and quickly disappeared within a turbid atmosphere of quite dense fog. This day, in accordance with my fate and spiritual state, was completely “bad”, as they called it in Shkodra at the time. In an instant, I remembered a topic for my essay “Sadness in Nature, Sadness in Our Hearts”, which the late Professor Qemal Draçini had given us two years ago, and I quickly brought my mind to the prison that awaited me and the misery that I was leaving at home.

So, having fixed myself for a few moments, and taking with me the memory of an environment in which I had grown up, I had no need to prolong such weaknesses any longer and from the top of the stairs, I shouted louder than before “Farewell”! And I let myself down, as if carelessly, because they were young people from the dampness of several days of bad weather. All the people in the house responded to my greeting as if they were acquaintances, wishing me from different directions, some with; “Have a good trip!” with; “May you be safe”! Someone else; “May God protects you!” etc.

As if for more trouble, as I descended into the courtyard, I heard the soft footsteps of my younger sister, less than five years old, hurrying to show me her beautiful face through the wooden railings of the large veranda, saying to me as if in a whisper: “I’m falling back on my father”! It was about three hundred grams of wheat bread, which as a baby, she had started to enjoy with particular trepidation since four days, and which during those few days, I had brought her when she left school.

Before I passed the door of the yard, as if to take with me the last memory of the house, I stopped once more, and as I was observing her, a feeling of pity seemed to me to be experiencing for her too: strangely, that day, she seemed to me older and more desolate than ever! Although I was leaving behind a house in misery and tears, I gathered myself and, thinking of nothing more, set off alone for school. As soon as I entered the school yard, the bell rang and the students began to gather in rows as if after classes.

I, as those expelled from the “Youth Organization” with the “ceremony” they had known the day before, together with Asime Pipa, Abdulla Miloti, Qazim Borshi, Marie Rranxi, Linda Boriç, Suzana Laca, Dodona Karafili and some others, as per the rules, took my place at the end of the row, without the need for one of those disgusting lackeys, who was heading towards me for that purpose, to remind me. And in the classroom later, as soon as I entered, the same person, Ferit Mandia, who was the personification of the worst spirit and ugliness as a human being, pointing his finger at the last bench, would tell me as if with authority: “There, at the end!”

It was the second hour of class when Mark Manovi, the head custodian of the school, entered the classroom and, addressing Professor Jorgji Kono, who was explaining his physics subject, said: “They are looking for Ahmet Bushati in the principal’s office.” As Mark Manovi was repeating the principal’s message once more to Professor Jorgji Kono, who was not hearing well, I had left the bench and approached his desk, from where I greeted him with a bow and then led him to the classroom, I was about to say loudly: “Farewell, friends,” and leave the classroom.

Accompanied by Mark Manov, I walked down the corridor to the door of the director’s office, which I opened and saw Shaban Saiti, the Sigurimi officer, sitting in a chair at the front, dressed like a civilian, who knew us well, as in the patronage that the gymnasium had had two or three years earlier. As I took one or two steps inside the office, I looked only at the director Fadil Hoxha, whom I greeted with a nod, while he, – I have the impression that it was with regret – half-standing up and without taking his eyes off me, would extend his hand to the Sigurimi employee, telling me: “Comrade, I have business with you” and before he had even finished speaking, Shaban Saiti, for his part, perhaps for the sake of a rule that they should have, would suddenly throw it into my arm.

When we went out into the corridor, I said to him: “I have my coat on the hanger, can I take it?” He nodded, accompanying me closely along the corridor. I was sorry that I was leaving without even saying goodbye to Simja, with whom we had just started writing a novel, but who was missing that day. On the way to Sigurim, Shabani would never speak to me – and he would never speak to me during the year and a half that I would stay in Sigurim – except for one time when, that same day, on the way to Sigurim, he would ask me: “When is your big break?” As I would later confirm, Ernest Përdoda was scheduled to be arrested during the big break that day.

As I walked, I looked around for someone I knew. I felt a great need for someone to see that I was not afraid, so that my family would know first and have it as a consolation, as well as my friends, so that they would continue to believe in me. I had never hated communism as much as that day when I was heading to the Security Service, and I had also never felt such courage and inner strength in myself as that day! The pain for my family, the strong upbringing, the ideals we had nurtured over the years, as well as the bequest from my father one night earlier, were gathered and concentrated in one point, ready to explode at the first opportunity. I don’t know what others have felt in such cases, but that day, both on the way to the Security Service and during the investigation back, I constantly felt the need for a challenge and a strong reaction.

With this burning spiritual state and with a burden of secrets on my back, determined not to speak about anything or anyone, I crossed the threshold of the Sigurimi, the threshold of that hell where for more than three years, innocent people were tortured and killed. When we went upstairs, Shabani, without ever letting me go, tried to open several doors in search of the person who would interrogate me. In his absence, as if off duty for that occasion, I was received by the chief Lilo Zeneli himself, who even after more than three years since the War had ended, continued to wear a piece of black gauze over his eye, which had been damaged since an attempt with the fascist militia, carried out somewhere in the mountains of Domni in 1943, when he had also killed Tomë Kola, a former boarding student of “Maleve Tona”.

That black patch over Lilo Zeneli’s eye, even in those moments, continued to remind me of his loyalty to the war and its ideals, but what if he, as undeveloped as he was due to his almost complete lack of education, would never understand that with the work he was doing, he would be nothing more than the most realized personification of the confusion, that is, of the contradiction between the good intentions that the War had, – in accordance perhaps with his natural inclinations – on the one hand, and the negative consequences that that war had, including his personal decline as head of the Sigurimi, something that he would not understand at all and perhaps never, despite some moment when he would swing like a bad and uncontrolled pendulum.

Even if he were to be less negative than his criminal subordinates, the fact that he continued to be at the head of a veritable organ of violence and crime, where deceit, treachery and cruelty were some of the basic instruments of his inhuman work, having mercy on him, could be characterized as after the biblical prayer: “Forgive me, O Lord, for I know not what I do”!

So I found myself in the office of the boss Lilo Zeneli, where his artificial tricks and smiles, as artificial was the tone of his hypocritical speech, and also the taunt he tried to serve me with politeness, like a trickster he would be even if he treated me as if I were a man with whom citizenship and war continued to connect him, all of these showed that his party had not had any difficulty in corrupting the uneducated Lilo Zeneli, from a simple man and a good fighter, and turning him into a blind mannequin of its own.

He had me sit on a chair, while he himself stood on his feet, facing me, behaving in peaceful poses both towards me and towards the police major with a deadpan face, a certain Shaban Haxhijet, who never opened his mouth there, but who, as a courtesy and as a sign of approval, would constantly accompany Lilo’s words with a slight smile. Among other things, that day Lilo would tell me: “We have nothing to do with you. You, for example, may have made some trivial mistake, which we know, but we have called you here to tell us about your friends, what they have done, how they were dissatisfied with the reforms that affected them”!

The artificial tone and the naive way in which he was treating me made me feel quite offended. I was not a child to deceive them as he disdained and believed, when in the most serious way I happened to be there arrested for anti-government activities, something he knew as well as I did, so to his hypocritical expressions like; “you, like the war you were”, – when in fact I had only one child – and “they are not affected by the reforms”, etc., I could hardly wait to answer: “they too – if we were talking about Xhevat and Remzina – have helped the war as much as they could, and as for the reform, it has also affected my house”, something that Liloja knew, but which was pushed by duty and purpose, he would intervene to me supposedly as a friend, as if we were in a café and not in the office of a Sigurimi chief: “And what has the reform done to you?! A very small thing, which is not important at all”.

With that, this first, not very official session was closed, and I was taken to another office, waiting for someone to take me. After about an hour of sitting there in a chair, where, out of fear, none of the villagers who came and went there for work and were tied up with the documentation of the weapons they were carrying did not speak to me or even look at me, suddenly the door of the office was forced open and a tall, thin officer, with a dry face and a serious expression, a “Mavruke” – as they call him, addressed me with all arrogance: “Are you Ahmet Bushati”?

“Yes”, – I answered without playing the part. Perhaps because of my somewhat indifferent attitude, he would intervene even more in a tone: “Do you know where you are”? and would add emphatically: “Come with me”! The investigator I was following down the corridor was Sirri Çarçani, a name I would learn a few days later. In addition to the ugly face he had – like that of a monkey – what caught my attention about this man was a gait with both knees that broke very rhythmically as he walked, just like those mountain people who had never seen a city with their own eyes. And even more than this, perhaps the careless and lazy way of walking, led me to believe that I was dealing with a piece of ignorance, who in my case was getting carried away by the pleasure he must feel from the fact that he had me in his trap.

We soon found ourselves in his office, facing each other: I sat on the incriminated bench, and he, on a chair with a table in front of him. With his face more rude than serious, he began to ask me questions quickly and in a way that required short answers, such as; “Yes”, or “No”, “I know”, or “I don’t know”, “It is” or “It is not true” etc. From the beginning, this investigator would point out to me the importance that a “good attitude” on my part would have for me and, at the same time, remind me of the strength and determination of the Government to fight mercilessly and to the end against any of its enemies.

Since the session was lasting several hours, he would also find time for his cunning twists, when, supposedly for my good, he would advise me as if in good faith and in quite human tones: “You’d better finish the job with me, otherwise, if you pass into the hands of others, you will have a very bad job”. Sometimes he would address me with words that were sometimes harsh and sometimes soft, and, as the case may be, he would alternate his tones and also create short or long pauses, so that I would have time to reflect before breaking down.

After a gentle advice, in order to somehow achieve the goals he had for me, he would suddenly explode with ferocity and threaten me, mock me behind my back, and so on, leaving nothing unsaid from his arsenal as an experienced investigator and criminal that he was.

The most obvious thing in his attitude would be his deep and class hatred for any opponent, for which in this case, my surname “Bushati” alone should have been enough. Once he would tell me that I should also pay for my father, and when I told him that; “my father is not involved in politics”, he, like in the fairy tale “The Wolf and the Lamb”, would growl and shout even louder, and would add: “You will also pay for your grandfather and others before him”.

During this first interrogation session, I would several times examine his sour face, spoiled by nature, in which not a single trace of humanity would be discernible, confirming once again what we had repeatedly expressed with our friends: “Even the muzzles of these Sigurimi betray their souls”!

In that evil and nervous face of his, in which hatred for people and perhaps even dissatisfaction with himself were clearly carved, I would also notice his protruding lips, which, apparently, as a sign of annoyance and contempt, especially the lower one, had become droopy. Or didn’t those lips look very red against the yellow background of his face! Let them realize that every feature and muscle in that face, from eternal dissatisfaction, had taken shape as if after the impressions that that evil and arrogant man must have suffered during his life. He must have also weighed himself down.

From time to time, from under the table, he would select some of my photographs and then present them to me as compromising evidence, as if they were of Churchill and Roosevelt. They were photographs that he had brought to U.N.R.R.A. in bulk, right after the end of the War, without excluding those of Tito, Stalin, Enver Hoxha and Mehmet Shehu, which we had bought in the store out of that little bit of confused nostalgia, still left over from the inertia of the War. Along with them, during the search that the Sigurimi had carried out at my house that morning, they had also confiscated two diaries from me, from which Sirri Çarçani would take the opportunity to delight in blaming and mocking me for words and phrases that he had torn from them, which, with the aim of intimidation, he would recite to me with the necessary intonations.

Also, in order for me to know who I was dealing with, he would directly or indirectly try to convince me of the culture he possessed, especially of his “dialectics”, which he would boast about in front of me, even though I was young and a prisoner. On that occasion, he would also speak to me ironically about Qemal Dracini, when among other things he would tell me: “He remembered what he was and found what he was looking for”! And it never occurred to that devilish and immoral investigator, about the opposite effect that his statement had on me, not to mention that Qemal Dracini had been our most respected and beloved professor, and one of the most painful victims for our city of Shkodra.

And he was not ashamed! He had been a classmate of Qemal Draçini at the Shkodra high school, but in this case, perhaps due to an intellectual inferiority complex that he had experienced towards Qemal Draçini, he had the opportunity to maliciously seek to find a reason to denigrate him even for a moment. Years later, when we were at a work camp for the construction of a military airfield near Berat, a man from Vlonet, speaking about this Sirri Çarçan, would tell us:

“It was Sirri Çarçani, that man-sucker, who would run from Tirana to the Vlora prison, to communicate to his former mathematics professor at the Commercial School, Bego Gjonzeneli, so honorable and patriotic that his request for clemency had not been taken into account, and he did not regret it at all, to also tell him the time of night when he would be executed. In the end, Begua, had turned to that evil communist, who had once been his student: “It was me, who once welcomed you to the anti-Italian demonstrations in Vlora”!

Finally, after about two hours had passed after lunch, Sirri Çarçani, after so many accusations, provocations and threats he had made to me, as well as after so many lectures with which he sought to convince me of his level of culture, would close that first session with me, repeating to me: “Now go Think about it there in the dungeon, and when I call you later, talk. You’d better finish your work with me, because if you leave it in the hands of others, you’ll have a much worse job. For better or worse, to speak, you will speak like a nightingale”.

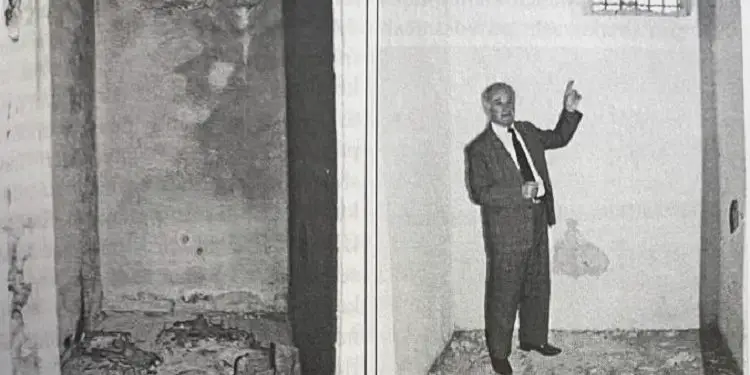

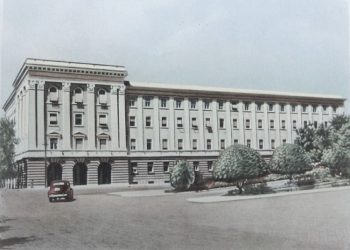

Accompanied by a policeman, I walked through a large courtyard that came behind the Sigurimi building, at the end of which, to the right of it, extended a ground-floor building, with an entrance without a gate in its center and with two high windows under the roof. The entrance, three or four meters long, divided the prison on the left and right into two dungeons with three corridors, each of which extended with seven pairs of dungeon doors placed symmetrically facing each other, ultimately fourteen of them looking out onto the courtyard, through several small windows attached to the high ceiling, and fourteen more on the dark side, which were intended to receive some light from a corridor that was barely illuminated by only two small skylights, one at each end of the hips, light that little by little, could perhaps enter the two or three dungeons closest to them. Memorie.al