By Ahmet Bushati

Part twenty-one

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

There could be many citizens of Shkodra, or even individual families, who would be persecuted and imprisoned, or even killed by the communist government, even though at that time they were not working or even living in Shkodra. For example, I would recall on that occasion two well-known Shkodra families, Gera and Rasha, living in Tirana at that time, with which communism would be very cruel.

From the Gera family, three brothers would be put in prison: Rroku, who had once been the Minister of Finance and, as such, had been convicted by the special court; Laca and Tefa, who had been involved in trade, were also convicted. His son, Zefi, who had graduated in chemical engineering, was also convicted. The Rasha family, all five males they had, would be arrested.

Lorenci, who in Italy had received the title of “Doctor in Literature”, would be shot. Brothers Pjetri and Gjoni would not really be sentenced to death, but their sentences would still be so severe that no one would come out of prison alive, while Cini, who in his youth had been an actor at the “Bogdani” theater in Shkodra and who generally, played female roles due to his suitable voice and his plastic appearance.

In Italy he had also attended a cinematography course and, in addition to the above, having also become one of the veterans of Albanian cycling, had also attempted to complete a tour of Europe by bicycle. Finally, this charming Cini, with an artistic and sports bent, communism would sentence him to ten years in prison. Gaspri, who had graduated from the ‘Normal’ of Elbasan and, later dressed as an officer, would serve four years in prison.

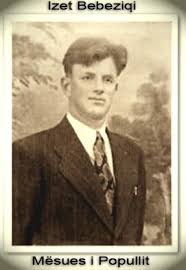

Another patriot and intellectual from Shkodra, Izet Bebeziqi, were arrested in Tirana, who had completed his secondary and higher education in Austria, having also been a student of the distinguished Albanologist Norbert Jokli, and later his friend. He would be one of the rare Albanians who knew ten to eleven foreign languages. He would be at the side of the youth of Vlora, in their demonstrations of April 7, 1939. As a former participant in the demonstrations of Tirana, and even though in Korça he had led the students in tearing down the Italian flag, he would be interned in Italy, for the period 1940-‘43.

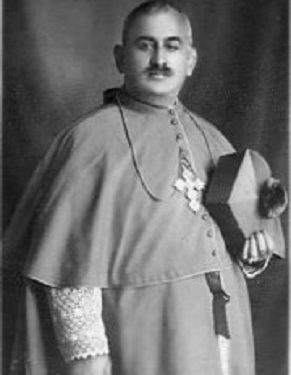

Even the Germans would imprison Izet Bebeziq, if such a personality and patriot were to be sentenced to seven years in prison, it would, of course, be the communists. More or less around this time, four other Shkodra citizens and cultural personalities were arrested in Durrës, three of whom were relatively young. Thus, the priest Father Vincens Prendushi and the professors Preng Kaçinari, Simon Deda and Arshi Pipa were imprisoned there, while they were teaching at the gymnasium of that city. Father Vincens Prendushi, – with whose name those beautiful poems that we had memorized when we were children are associated, had been put in a cage with Arshi Pipa and the Mufti of Durrës, Mustafa Varoš. One day, Father Vincens would be found hanging in a toilet of the Department of Internal Affairs, whose eyes would then be closed by Arshi Pipa.

Tragically, Professor Simon Deda, who had graduated in forestry agronomy in Florence and was known for his broad cultural horizons, would also die at the age of thirty-eight. After having tortured him to death in the interrogation room, one day the criminals of the Sigurimi, Professor Simon Deda, would throw him, massacred, from the window of an upper floor of the building and down to the sidewalk, and, as usual in such cases, they would say that; “he had thrown himself”!

Another respected and tubercular professor, Preng Kaçinari, who had graduated in philosophy in Montpellier, France, and who had previously taught at the Shkodra Lyceum, also happened to be in Durrës prison. As a patriot and nationalist, in the summer of 1943, he had even gone out into the mountains with a gun in his hand, having also been one of the members of the “Ballist Circle” for Shkodra.

After two or three years of being released from prison, tired and desperate as he must have felt, both from the constant persecution, and from his old tuberculosis disease, and perhaps even more so from prolonged unemployment – to the point where he sometimes could not even make ends meet – add to this his sensitive nature and strong character, all of which together would lead to his tragic death one day, committing suicide somewhere in the graveyards of Tirana.

A conclusion like that of Professor Prengë Kaçinari does not only belong to sentimental young people in a deep state of despair, but also to the strong, for whom life has no meaning when it does not may have more dignity. Another group of citizens who would be arrested around this time were former students of the prestigious American school, with principal Harry Fultz, such as Qazim Dervishi, Ruzhdi Baja, Lec Barbullushi and Xheladin Baci, when each of them would have left behind a young wife with small children at home, and one of them, Xhela, after two years in prison, would lose his ninety-year-old Mentor, his only son, whom he would mourn with a very touching poem, which he had only recited to us once in prison, trembling and with tears running down his face.

Meanwhile, in Gjinokastro, Paulin Shestani and Xhela Kamata were shot in vain while serving in the army, the first as a veterinarian and the other as a soldier:

Among the three brothers “Thani”, two of them, Marku and Deda, would pay their duty to martyred Kosovo, the first with life, and Deda, with 14 years in prison. The two brothers, Pali and Marku, had headed a military academy in Italy. Pali had also specialized in finance, and Marku in “Fine Arts” in Florence. Captain Pal Thani, although handed over under an amnesty, would be tortured by the Sigurimi, until he died at the hands of the executioner Fadil Kapizyzi, while Marku, so respected by everyone, would be shot in Prizren by the criminal Shefqet Peçi, along with 11 other innocent nationalist officers, among whom was another officer from Shkodra, Ndoc Paci, who had served in the army there in Kosovo liberated from the Serbs, with whom Shefqet Peçi, as a former career officer himself, had a colleague:

The criminal Shefqet Peçi, at the head of the 5th Assault Brigade, on its way to Kosovo, had stopped in the village of Buzëmadh in the Luma River, and after eating their bread, the next day, in revenge for a nephew who had been killed a few days earlier, somewhere in those parts, he would treacherously kill 21 innocent men.

Another respected professor, Kolë Margjini, would also fall victim to communism, coming to Shkodër from Kosovo, where he would spend most of his life and, where he had first excelled in primary and high school and received a scholarship to Austria, Vienna, where he graduated in pedagogy and where he had also attended an institute of oriental languages.

We returned to Albania in 1913, he had initially taught in the city’s elementary schools, and with the establishment of high schools, he had taught pedagogy in the school of the same name and mathematics and German language in the gymnasium.

He had participated in the Educational Congress in Lushnja in 1920 and later served as an inspector at the Ministry of Education. In 1941, with his ardent desire, he would go to his Kosovo, liberated from the Serbian yoke, and in Prizren, he would be appointed director of his first high school, and moreover, he would be one of the main organizers of the “Second League of Prizren”.

When the Serbian partisan brigades would reoccupy Kosovo, Kolë Margjini, to avoid any possible mistreatment from their side, would be returned to Shkodra, in which case the Albanian communists, with the malice of the unpatriotic and servile towards the Yugoslavs, would hand over the honorable and patriotic Kolë Margjini to the latter as a war trophy, who, in turn, would sentence him to prison, from which he would never come out alive.

In a relatively limited work like this – as we have repeated several times – it was not possible to include the imprisonment or even murder of many families. For example, the Muftia family, one of the most respected and persecuted in Shkodra. Its head, Sali Effendi, the mufti of Shkodra and a figure of Legality, before the communists entered, would be forced to take the path of exile together with his eldest son, Fuat, and with Zijana, his nephew, and his family would be interned from the very first days, with both the eldest and the youngest. And after the first few years, he would be interned for the second time, to suffer yet more years of internment. One of his sons, Feridi, when he was a student, would serve years in prison as a former member of the “Albanian Effort” organization, and much later, Mit’hati, who came after him, out of despair, would one evening throw himself under the wheels of a large car, ending a life he could no longer bear.

Likewise, the Toni family was only told about Ignaci, who had spent a few years at university in Italy studying political science, and the imprisonment of Luigi, who was so talented that he, at the same time as Ignaci, was studying mathematics in Italy and who would one day also serve prison, was not mentioned, just as their younger brother, Kola, who had secretly attended classes to become a cleric and served twelve years in prison, was not mentioned.

It was also not mentioned that from the Boriçi family, while one of their sons, Fejzia, was in prison in Burrel, his younger brother, Nexhati, was experiencing the most difficult adventure, staying hidden for three years in the depths of a cave in the mountains of Repisht, and having been fed by a mountain house, a loyal friend of their house. And likewise, there was no mention of the internment of their eldest brother, Hajri.

Another prisoner at that time was the charming pharmacist, Alfred Ashiku, an unrivaled billiard player in Shkodra and who, in terms of physique and especially appearance, “had hardly found a match even among film artists” as it was said about him at the time in Shkodra. In connection with this, we are telling only a small episode, mixed with the suffering of humor:

As a prisoner in Tirana, in the summer of 1948 he had also been to the Vloçisht camp. One day, while returning from work to the camp, exhausted to death as he was, he picked a beetroot in a field that was falling on the road they were passing. It was dictated by the police, who, as punishment, forced him to walk the entire way with a beetroot in his mouth. With a beetroot in his mouth, he would have been forced to stay inside a hole when, after being returned to the camp, they would bury him alive, leaving only his head outside, and of course, always with a beetroot in his mouth.

Myfit Myrto Bushati, a prisoner and camp inmate with him, would tell how he spoke to Alfred about that incident, and what answer he received from him: “Alfred, how did you not lose your breath from that “alamet” of beetroot in your mouth, both on the way and when they covered you with earth behind you?” And Alfred: “Myfit, I’ll tell you exactly – exactly, I’m telling you that during that whole time, you didn’t think about anything else, except saying to the vet: “Are you saying they’re going to let me eat the beetroot now?”

There was no mention of the Shkodra residents in Burrel prison, among whom are some who may have died there, and there was also no mention at all of the numerous Shkodra families interned, even during the period I am describing, proving that the extent of the persecution of Shkodra is much greater than what has been presented so far.

You should not have definitively left the period for which we continue to talk about and without including many people and events that would belong to it, as far as was said up to this point, wouldn’t it be enough to prove that communism, Albania in general, but Shkodra in particular, was fighting with fury and without mercy precisely for what it had and what it would have in the future? That it was fighting it at its roots and in essence?

Without including the prisoners arrested before the Postrriba uprising nor the others after it, with all these prisoners that were talked about up to this point, who, in any case, are only a part of those who were imprisoned on that occasion, all those people shot, drowned under torture or died in prisons, who are also again a part of their total number, don’t they prove that the communists, having believed in the axiom formulated by them “as the proletariat that was “gravediggers of the bourgeoisie”, so could Albanian patriots and intellectuals, classified as “bourgeois”, one day be called gravediggers of the proletariat”? This is the reason that pushed them to build that strategy of physical extinction and spiritual subjugation of the most vital and cultivated part of our Nation, wherever it happened, in Albania and Kosovo.

So, all these valuable people that communism massacred on that occasion in Shkodra, all those diplomas that it burned, good houses and a village that it ruined forever, many innocent lives that it prematurely buried, and the happiness of so many families that it turned into tears, well-being into misery and above all, brotherhood into filth, all together, are they not an unspeakable act of barbarity, a true calamity and a genuine genocide inflicted on the people by some of its sons who had become communists?

However, at a time when Shkodra was suffering under the weight of daily terror and a deeper misery of life, having only a ration of corn bread per capita that would initially range from 250-400 gr. per capita and later from 400-500 gr.; and when hundreds of families were counted who had one or more of their members in prison, that communist government would not have been ashamed to boast about all of the above, calling it a victory over enemies and traitors.

In the wake of the great changes, even the holidays would be new, young people and jubilees. Thus, precisely in the darkest days of that 1946, coinciding with the one hundredth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, – which in our country was expected to celebrate with the greatest possible grandeur – since a few days before, sensational press articles with disgusting headlines would precede that anniversary, pointing out that the good things we were enjoying had their mother in a revolution, which, according to that press, was “shining more and more every day in all four corners of the globe.” etc. During December of that year, the sixtieth anniversary of Stalin’s birth would fall, on which occasion random article writers would struggle to find epithets of the most unattainable in terms of superlativeness, such as: “Long lives Generalissimo Stalin, the most brilliant man of our time, the leader of millions of workers throughout the world!”

Time, as we have said above, had brought the need for appearance and gloss even for the communists themselves who believed in the morality of the line, for whom it had begun to become clear that conscience and honesty were no longer valid, that the basic elements of human morality were now considered insufficient and completely unnecessary for the policy of the dictatorship’s power.

In a word, they were looking for visible supporters of party policy, cheerleaders, servile and spies. The psychosis of fear and uncertainty wanted to penetrate deeply into every citizen, including the communists./Memorie.al