By Ahmet Bushati

Part Nineteen

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

The other family members, driven from their homes, would spend their entire lives at the mercy of neighborhood councils or any of their relatives, who would shelter them wherever they could. Pjetër Saraçi, the older brother of the history professor, Angjelin Saraçi, had also been imprisoned, having gone to fight in Kosovo with the “Besnik Çano” battalion, but without having been a ballistics officer, but a “nationalist”, as he would express himself on the day of his departure there, and would later serve about a year in communist prison for that.

Their brother was also Ludovic, a former gendarmerie officer, who, with the arrival of the communists, had fled to Mirdita and was killed in an attempt by the Sigurimi forces in a place called “Bjeshkë të Kaçinarit”.

From the old Serreqi family, intellectuals and in good economic standing, with the events of Postrriba, all four brothers would be imprisoned at once: Gjoni, Ejlli, Luigji and their youngest, Cini. Gjoni, as the eldest among them, had been involved in trade and generally in the administration of the family’s wealth all his life. After him came Ejlli, who had headed a trade school in Austria, and who had been a deputy during Zog’s time. The two youngest brothers, Luigji and Cini, had attended military schools in Austria.

One of the five brothers was Zefi, who had also pursued a military career, but they happened to be in Italy on the eve of the invasion of Albania. Gjoni, after serving ten years in prison – most of it in Burrel – would serve another five years of exile, together with his family. Ejlli and Luigji would be sentenced to a few years in prison, while Cini, although in vain, would accuse them of being one of the main organizers of the Postrriba Uprising and their house as a meeting center, causing him to sentence them to death and shoot them.

The Sokolej family was famous in Shkodra, not only as the heirs of the patriot Hodo Pasha, but also as a generous and emancipated house, a house around which a wide circle of friends and well-wishers gathered. The eldest son of the family, Brahimi, who had graduated in Jurisprudence in Yugoslavia, would be arrested before the Postrriba Uprising, as a former exponent of Legality for Shkodra. With the events of Postrriba, Isuf Bey would be arrested, along with his other son, Ramadan, who had studied flute and composition in Florence, and they would each serve two and four years in prison, respectively, while Brahimi, upon completing his five-year prison sentence, would go into exile for life.

Hodoja, the third and last son of the family, had been sixteen years old when his father and two older brothers were in prison, but when he grew up, he too would be arrested among the students, who would then cry when they saw with great horror and amazement their respected teacher in irons, who would later, as one of the most prestigious Mandels of Albania, serve with great dignity over twenty-four years in prison, most of them in Burrel and in the Spaç camp.

Safeti, the fifth of Isuf Bey’s six daughters, who had previously been presented as a talented singer to the Shkodra public, and sometimes even to that of Tirana, Safeti, that charming young student, who until then had attracted the attention of many for her free and sincere temperament, would have liked to sacrifice, starting from that time on, once and for all, every dream and spring of her future life, to put herself at the service of the survival of her imprisoned or interned brothers, for whom the streets of Myzeqe, Kuçi lab, Spaçi and Burrel, for many years in a row, were her only destiny. And when Hodoja, after so many years in prison, returned home, he would find Safet, a very old woman, with a head as white as snow, because by then a full forty-four years would have passed since she had been running after her brothers through prisons and exiles.

From the old Suma house, which in Shkodra dates back to the 14th century and perhaps even earlier, a house that from time to time had produced prominent people such as doctors, consuls, translators between consulates, etc., on the occasion of the Postrriba uprising, two of its last suckers were arrested, the brothers Gulielm and Gasper Suma, the former who had used the famous Kafe e Madhe, while Gasper, a priest, was accused of the same uprising, with which, like Gulielm, he had no connection.

Gulielm, accused as one of the main organizers of the uprising in question, would be shot, while Gasper would be sentenced to years in prison, but nevertheless, he would not leave there alive. Gulielmi’s two daughters, Terezina and Irena, would also serve a year in prison.

On the charge of “knowledge of the Postriba Movement”, the strong Hafiz Musa Dërguti was also arrested, about whom he would tell them that when he was in a detention room with Gjon Serreq and they were tied hand in hand with him, they had been raised and lowered together as if they had been one body, whenever during the day and night Hafiz’s meal came to thank God, as a Muslim and as a hoxha that he was. During those days, Father Frano Kiri was also arrested, who like Hafiz Dërguti, and would later serve ten years in prison and another eight in exile. At the same time, Father Donat Kurti, former director of the Fretënve and Stigmatine Gymnasiums, a polyglot and renowned folklore scholar, as well as a collector of the famous “National Tales”.

After seventeen years in prison, mostly spent in Burrel, Father Donat would emerge sick and old, and would extend his life for a few more years, having lived in the basement house of a poor relative of his, somewhere on the edge of Zall i Kirit, where he would eventually close his eyes forever.

Father Gjon Karma, the last rector of the Jesuits, was also arrested, as was another priest, Dom Tomë Laca. Dom Pjetër Gruda was also arrested, who after serving the eight years of his first prison sentence, after many more years, would be arrested a second time and sentenced to another eight years, to die just a few days before serving them too.

Shortly after this time, Friar Gjon Pantalia, in an attempt to escape from the prison of the Assembly of the Friars, would be captured alive and die under torture. Also arrested at that time was the former gendarmerie officer, Kolë Zadrima, who would be locked inside a very dirty W.C., which smelled so bad that it burned his eyes and made him want to breathe.

After several endless days and nights, he would find salvation by tying a thick, bare wire around his neck, so that when the current came, it would strangle him on the spot, just as he had drowned, thus ending not his life there in the former house of Çurçi, turned into an investigator and prison, but the torture, and especially that unbearable V.C. that was deliberately left him so and in the same way, as a result of the torture he suffered, Nuh Oroshi, known in Shkodra for being very generous and a man of good character, would die at the age of seventy. Years would pass before his only son Xhela would also be imprisoned and serve eighteen years in prison.

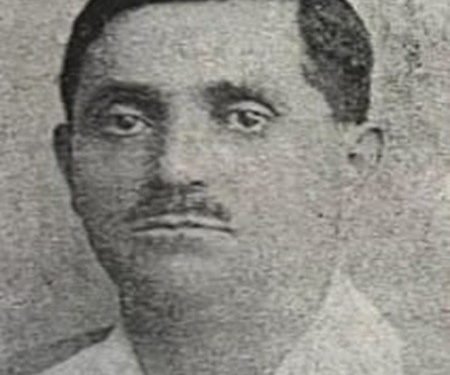

Messrs. Mustafa Dragusha and Dulo Kali, the former owner of a large flour mill and a modern pasta factory, and the latter, the former owner of the famous “Salo Kali” Inn, in the “Rus” neighborhood, were known throughout Shkodra and Malce. Both were devoted to household chores and were completely excluded from politics. They would be accused as two of the main organizers of the Postrriba Movement, sentenced to death, and shot.

From the Dragusha house, Hyseni, Mustaf Dragusha’s nephew, had also been arrested, for a few years also a former university student in Italy, and who, after the first prison sentence of several years, would serve a second one, longer than the first. Simon Darragjati, a well-known citizen of Shkodra and grandson of the Dedejakupevs, after several days of torture, would jump from a window on the top floor of the Sigurimi building and fall to the ground.

When the “Postrriba Uprising” broke out, Rasim Gjyrezi, together with his Harapesh wife – an Arab woman who, like other Arabs like her, would serve for years in several Muslim homes – happened to be out in the village of Krebaj on the Mountain Side, and one day, very soon after that uprising, he would find himself surrounded by Sigurimi forces. As the patriot and brave man he was, he would immediately fire his rifle. It is said that he had two long rifles with him, that whenever Rasim Gjyrezi ran out of cartridges for one rifle, he would have the other ready from his wife who would fill it for him while standing by him until he killed them, after a relatively long fight.

On that occasion, the house of Hysë Dobrovoda, where he had stayed for several days in a row, together with each of his cousins, with the boards removed from the floor of the rooms, they would quickly make a coffin, and in silence and with respect, they would bury the brave Rasim Gjyrezi, somewhere for the end of a prozhmi.

And who would not arrest them during those days! Not a single night could go dark or a single day dawn without their arrestees. Especially in the early hours of the morning, citizens, as soon as they met their friends, would announce the arrest, or the latest arrests, and separate them, uttering curses like “Hupi, God”! “What is going on”!? “What have these hours been like”!? etc. The thirteen prisons opened by acquaintances, if they had been schools, would have been worthy of teaching the children of a city with less than fifty thousand inhabitants that Shkodra had, at that time.

At that time, Dioniz Miçaço, former chief judge for years in Shkodra, was arrested. In prison, he would be one of the most respected people, both for his strong character, for his extensive culture, and for being a foreigner in Shkodra. His confidential attitude even with us, the young people in prison, had made him not only a man from whom we had something to learn, but also an intimate friend of ours. I do not know the fate of a “History of Skanderbeg”, which he was writing in verse at the time, which, like several others, he probably took with him to the grave.

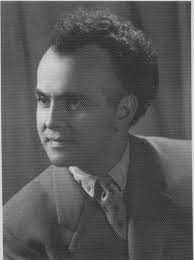

Another prisoner at that time would have been the professor from Elbasan, Mehmet Daiu, who had graduated in pedagogy in Geneva and who had taught pedagogy and French at the “Donika Kastrioti” pedagogical school for girls, here in Shkodra. Regardless of his age and culture, Mehmet Daiu would have been one of the people who, so to speak, had merged into our society during all the years of our common prison.

Qazim Dani, father of the future martyr Bardhosh Dani, one of the most respected gentlemen of the city, graduated in law in Istanbul and who had also been a deputy in the past, was also arrested. Honorable citizens of Shkodra were arrested on that occasion, such as Malo and Sulë Jubica, Zef Shkreli, Idriz Hoxha with his brother, Cufin, Riza Hoti, who was the father of my friend, Burhan Hoti. Ali Taipi was arrested, because he had sheltered the ballistics major, Bilbil Hajni, from the South.

Also arrested were Fet Dizdari and Smajl Elezi, sons of two well-known families, patriots and legalists. The chemical engineer, Jakë Serreqi, was also arrested at about the same time. The literature professor, Luigj Ljarja, was also arrested. Also arrested was Handi Hoti, a former ballistics young man and member of the “Besnik Çano” battalion, which had participated in the fighting to protect the Albanian lands of Kosovo from the Serbs.

Young nationalist intellectuals were arrested, such as Zef Zorba, Zef Toni, son of the former British representative in Shkodra. Also arrested were Sami Barbullushi, Rifat Barbullushi, Karlo Suma, Sirri Anamali, Hajro Ujkashi, all former university students, as well as younger ones, Bep Negri, Tomë Leci, Fuat Rrashi, Gjenarin Topalli, Gac Çuni, etc. Our mathematics professor, Adem Bazhdari, was also arrested.

The army officer with the rank of captain, Zef Ashta, was also arrested on the occasion of the Postrriba uprising, who, after serving five years of his first prison sentence, would be arrested for the second time, and after serving another seven years in prison, together with a loyal friend of his from Trush, a certain Gjeto Hasani, – with whom, by coincidence, they would serve their sentences more or less at the same time – they had decided in advance to escape together.

Gjeta knew the area they were going to cross by heart, since he had been in the army there, but unfortunately for them, he did not know that during the time he had been in prison, the “neutral zone” between the two borders, by agreement of both parties, had been extended, entering the interior of the two sides, the Albanian and the Yugoslav, respectively, so that when one day they crossed the border, as well as the old neutral zone, tired and happy as they would feel from the belief that they had finally escaped and escaped, they would sit down to rest. Not more than a few minutes would pass before they would suddenly appear with automatic weapons in their hands, the Albanian border guards: Zefi would imprison them for the third time, and Gjeta, for the second, so that no one would get out of prison alive.

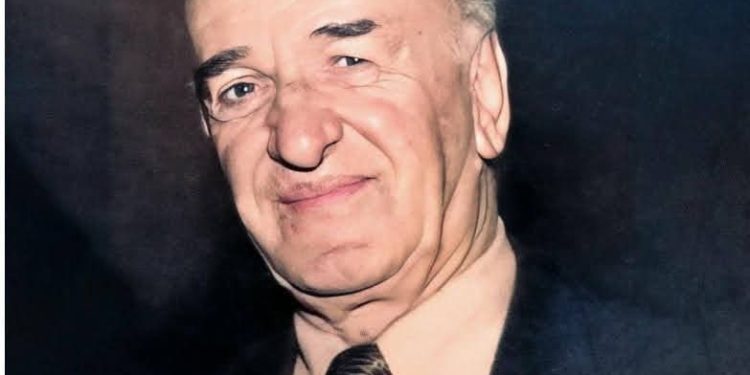

Paulin Pali

There must have been few people in Shkodra who knew that Paulin Pali, the brother of Captain Gasper Pali, had graduated brilliantly in jurisprudence in Florence, Italy, that from that university, he had been considered the best Albanian student at that time, that in the diploma exams for “Roman law”, for pleasure, he had given it in Latin and not in Italian, and finally, that that university had asked to keep him in one of its prestigious chairs, and that Paulin, respected for his Shkodra, had refused.

In the square of Shkodra where he walked in the evening, he would not have caught the eye of others, not only for his tall body, but also for his slow and wide-stepping gait, as well as for a serious elegance in his clothing. Above all, he was probably known to his fellow citizens for his admirable self-control, when he courageously defended the victims of communism among the people without being kidnapped. His dignified debates with the tendentious chairman of that panel of judges, Lieutenant Mustafa Iljazi, are also remembered.

Unable to bear the life of oppression and numerous deprivations any longer, Paulini would cast his gaze towards Italy, and when after a few days he, in the company of Atif Toptani and another person from the village of Gurëz on the Matë Coast, were waiting, as agreed, for a boat to appear at that place that would take them to the “promised” land of Italy, a squad of Sigurimi soldiers with handcuffs in their hands would be their final fate.

After Paulini had gone through the difficult tortures of the Sigurimi, one day, they would get into the back of a small pickup truck – together with Professor Kolë Prela, and set off for Fushë i Bunës, where they would be shot, just as they had been sentenced to death by a formal court just a few days before.

Xhemal Juka was also in prison, who, together with his younger brother, Galip, had suffered two years of imprisonment and exile in Italy, starting after the occupation of Albania. Xhemal, arrested in connection with the events of Postrriba, at the end of thirteen months of investigation and torture, in order to escape from the unbearable suffering and to leave with his honor intact, would one day end his life, performing a real act of heroism, when he cut his stomach and arms with a piece of glass that he had been able to secure for that purpose.

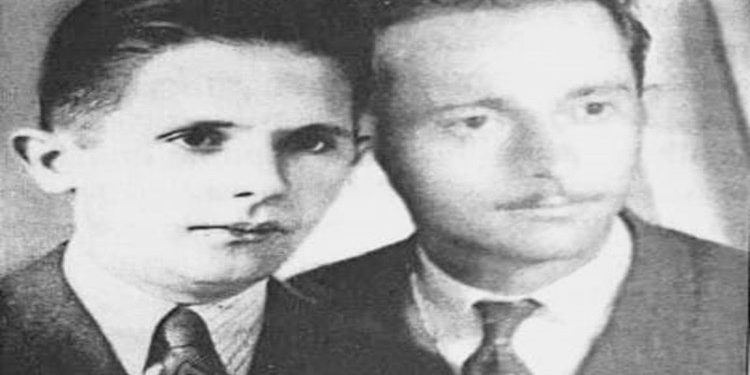

When the parents of Kolë and Mark Prelë, Prelë and Katrina, could no longer endure life there in the depths of their poor Dukagjin, they finally descended one day to Shkodra, taking their two young children with them. Prela immediately began working as a woodcutter, but as he was very ill, he did not last long and after a short illness, he died. Katrina, a widow, but strong as a highlander and strong, in order to earn the “daily” bread for her children and herself, was quickly “attached” to several Shkodra gentlemen’s houses, to wash their clothes. As a good mother, wife and lady that she was, she managed to raise her orphaned children with great difficulty and to give them an education, just as she had seen urban families do.

Years passed one after another and one day Kola would graduate brilliantly from the Fretën High School, for which he would receive a scholarship for higher studies in Italy and, ultimately, graduate in literature from the University of Turin. Returning to his homeland, he would teach at the Shkodra High School, until one day, together with his brother, Mark, – a high school student – they would go out into the mountains with weapons in hand. After the wars, Kola, as a former fighter of the brothers Kola and Mark Prela, of the National Liberation Front that he had been, would be elected as a deputy, although he himself was not satisfied with the politics of the regime.

When the trial of the members of the “Albanian Union” organization was held, Kola, out of obligation to the school where he had taught and respect for its professors, would come out to defend Father Gjon Shllaku, on which occasion he would declare, among other things: “The ‘Don Bosko’ Circle and the ‘Antonian Society’ were not political organizations, but religious and educational associations”.

Kola’s discontent, although expressed within a narrow circle of his close friends and acquaintances, would also reach the sharp ears of the Sigurimi, who eavesdropped on everyone, regardless of whether they had come from the wars. Both brothers would end up in prison: Kola, allegedly linked to the “Group of Deputies”, while Marku, as was usual at the time, for Postrriba.

After Kola’s death sentence, it is said that Katrina, her mother, had been locked in a garden in the Ballabane neighborhood for three nights in a row, hoping to see her Kola for the last time, when from there they would take her to Zallë i Kirit, the place where those sentenced to death were usually shot. To further despair for her, Kola – as we have mentioned above – would be shot together with Paulin Palin, in Fushë i Bunës. Memorie.al