From Sokrat Shyti

Part Forty

Memorie.al / The writer Sokrat Shyti is the “great unknown” who, for several years, has shown just the tip of the iceberg of his literary creativity. I say this considering the limited number of his published books in recent years, primarily the voluminous novel “The Phantom Night” (Tirana 2014). The novels: “BEYOND THE MYSTERY,” “BETWEEN TEMPTATION AND WHIRLPOOL,” “DIGGING INTO THE HORROR,” “THE SHADOW OF SHAME AND DEATH,” “COLONEL KRYEDHJAK,” “THE DIRTY HOPES,” “THE TWISTS OF FATE” I, II, “SURVIVAL IN THE COWSHED,” along with other works, all novels consisting of 350 – 550 pages, are in manuscript waiting to be published. The dreams and initial fervor of the young novelist, who returned from studies abroad full of energy and love for art and literature, were cut short early on by the brutal edge of communist dictatorship.

Who is Sokrat Shyti?

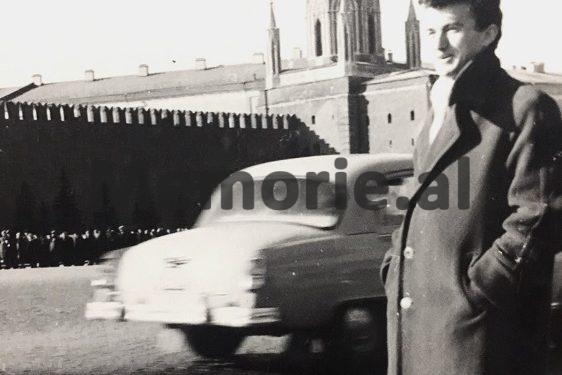

Having returned from studies at the State University of Moscow just after the break in Albanian-Soviet relations in 1960, Sokrat Shyti worked at Radio “Diapazon” (which at that time was located on Kavajës Street), in an editorial team with his journalist friends—Vangjel Lezho and Fadil Kokomani—both of whom were later arrested and executed by the communist regime. In addition to the radio, 21-year-old Sokrat, if we can imagine him, had passionate literary interests at that time. He wrote his first novel “Madam Doctor,” which was on the verge of publication, but… alas! Soon after the arrest of his friends, as if to fill the cup, one of his brothers, a painter, defected abroad.

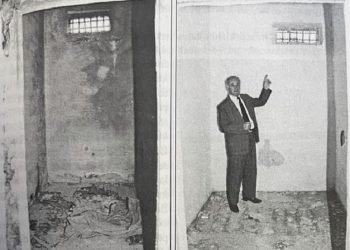

Sokrat was arrested in September 1963, and in November of that year, he was interned along with his family (with his mother and younger sister) in a location between Ardenica and Kolonje of Lushnja. For 27 continuous years, the family lived in a cowshed made of reeds, without windows, while Sokrat was subjected to forced labor. Throughout those 27 years, he was legally required to report three times a day to the local authority. He had no right to move from the place of internment and was deprived of any kind of documentation, etc. In these conditions, among a cowshed, he birthed and raised his children. It is precisely from this experience, or more accurately, from a very long story of persecution, that he based his writing of the book “Survival in the Cowshed!”

Agron Tufa

Continuation from the previous issue

EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK “SURVIVAL IN THE COWSHED”

– “I have a very simple question: do the internees perform mandatory military service?”

– “I understand. Since the first secretary of the Party Committee is rectifying some injustices against you, using the powers granted by his high position, the ill-intentioned still have one last shot left: the Military Department, the conscription call, hoping that during the two years of service, the big Party chief will change, and someone else with malicious intentions, who has class struggle in their blood, will come. I have no doubt that the provocation is internal, primarily from the executive, perhaps even from the chairman of the authority himself, who has set the lieutenant colonel in motion to undertake this illegal act, confident that they will have support from the mobilization directive in the Ministry of Defense.

If the new recruits’ list has been approved at the ministry, it means that the characteristics and respective explanations have been sent from here. And perhaps for you, since you are 26 years old, they may have used a distorted fact, that you were interned but are no longer, that your religious rights have been restored, including the Front’s tricolor, the notification letter; thus, you must perform mandatory military service. The other fact, according to the law, is that you are required to complete a six-month course, even if it has been mentioned, they must have accompanied it with the objection: a declassed individual cannot receive the title of reserve officer in the People’s Army.

This person must serve in work units, in the NBU. If they have crafted the request this way, and I do not doubt that they have fabricated it, the ill-wishers have won. First of all, you have no supporters in the Ministry of Defense. But even if you do, once the decision of the list is made, it becomes impossible to rectify any inaccuracies, be it a transfer from one unit to another, especially postponing the service for future promotion. Particularly for you, postponement loses its meaning, being at the age limit.

In my opinion, these maneuvers were precisely used to call you up as a soldier. Therefore, I lament your situation, as you are on the threshold of marriage. This has been the intention of your ill-wishers: to cause physical and emotional pain for two consecutive years, effectively increasing the punishment of the cowshed with a new form of retribution.”

– “My arrival here had two motives. The first, personal: I wanted to clarify my doubt. The second: to be grounded when I talk to my mother,” I emphasized to show my gratitude.

– “The fact that your mother had doubts about your conscription indicates that she has a sharp natural intuition,” the prosecutor noted.

– “It was indeed interesting how she posed the question: why was I not called these three years, while we were in the cowshed, but they remembered now?!”

– “A wise and quite accurate observation,” the prosecutor said.

– “With these few words, a powerful accusation arises, to which jurists cannot respond. Therefore, they have fabricated all those contrivances that I explained a little earlier. Since the opportunity arose for us to speak face to face, I want to ask about something: why was only half of the story published in the magazine ‘Nëntori,’ without the note it continues?! Did some order come from above not to publish the second part?”

– “Something must have happened. But what exactly, I do not know. Perhaps there was friction between the story’s editor and the chief editor. It is not said for nothing: when the horses fight, the frogs eat the kicks. Or perhaps an order came from above, as you guessed…” I replied.

– “Exactly with these various forms of entanglement, the unwanted talents are attacked. For there to be secure progress, talent needs political support. You lacked this, and that’s why you suffered so severely. But fortunately, a positive change has begun; you can now move freely without permission from your local chief, the Deputy. Therefore, if you have a little free time and happen to come to Lushnje, come by my office so we can exchange thoughts on literature.

Jurists, especially we prosecutors, are like Chekhov’s character, ‘The Man with the Briefcase.’ Because our routine work has put us into such rigid legal frameworks, it impoverishes our personal tastes for literature and the arts day by day, slowly turning us into the man with the briefcase…” he added, in a friendly tone, extending his hand to say goodbye.

The chairman of the Executive Committee lifted the receiver of the secret phone line and connected with the district chief prosecutor. Immediately, the chief of the prosecution was struck by an unpleasant irritation when he heard the voice of the power chairman, as it happened very rarely for the executive chief to remember and inquire about the proceedings and performance of the prosecutor’s office, not to mention he could not recall a single specific case to directly call this one about something. All these contradictions made him very curious, so he waited with unease and concern to hear the reason for this surprising call.

Initially, the chairman started the conversation with some ordinary questions: (How are things going over there? Can the prosecution handle the significant workload entrusted to it by the Party, as the most important and specialized legal shield of our socialist state, in this intense period of class struggle?). Right after these, the chairman of the Executive Committee left the district’s chief prosecutor stunned and shocked with his strange observation:

– “I want to know exactly: do you have any signs of concern from the internees of our district? Because according to some reliable information, I received data that today, one of your subordinates had a prolonged meeting with the former journalist of Radio Broadcasting. For this reason, I ask you to provide me with additional detailed clarifications on the purpose of this meeting!”

– “I’m aware of this meeting, comrade chairman, and I’m providing the answer right now, with one hundred percent accuracy: it was simply a personal meeting. As for the first part of your question, I tell you that we, as the prosecution organ, have had no provocation, complaint, or signal regarding the former journalist.”

– “You are delving into an unnecessary hole, comrade prosecutor, because you misunderstood my observation. I did not ask you if you called him personally, as those are your internal matters that you review with your subordinate specialists. I am interested in knowing exactly what purpose the internee had in coming to the prosecutor’s office and what he discussed for so long with prosecutor Bardhi?! Because, regardless of the nature of your profession and your specific duties as a prosecution organ, administratively you have the same subordinate structure between the links and the same centralization as the power bodies. That’s why I addressed you, as the head of the institution, and did not call prosecutor Bardhi directly. The head of the institution has specific obligations, beginning with the snooping of private conversations of subordinates with uninvited visitors, especially when the conversation takes place inside offices, and one party belongs to the group of declassed individuals. It is precisely in these typical cases that the revolutionary vigilance of the leader is demonstrated.”

– “I understood you correctly, comrade chairman. Considering that this conversation represents a special interest for you, I promise to clarify it very soon, and as soon as I am ready, I will call you immediately.”

But after these words, the signal was cut off! Instead of a response, the chief prosecutor heard the noise of the handset being slammed down on the apparatus. As he understood, the chairman of the Executive Committee did not like the last response, and in his arrogant act, he told the head of the prosecution: “Go, get lost, arrogant charlatan!” And agitated by nervousness, he began to fume like a madman. He almost bit his own tongue for not giving the chief prosecutor a piece of his mind himself! Why was he so straightforward, not spinning the conversation like he did with the lieutenant colonel of the Military Branch, whom he pulled by the bridle, just as he pleased?

But even starting that way, he still made a mistake: he shouldn’t have held back, allowing him to ramble on! He should have acted completely differently: made it clear and put him under his orders. Because the way he acted, instead of showcasing the powerful authority of the regime, the opposite happened; he behaved weakly, just like the mid-level state officials, who are cautious and carefully approach judges and prosecutors, under the oppressive shadow they carry with them, knowing that inevitably comes an honorable moment, when they’ll be knocking on their doors to urge them to release and untie the noose of punishment when it is around their necks, or to intervene to significantly ease the sentence of the closest people who have sinned, and they make this request not because their hearts burn for them, but out of fear that if they are punished according to the weight of their guilt, their political careers are seriously jeopardized.

The chairman was seething, caught up in this humiliating weakness, and allowed the chief prosecutor to sell him wind, when this could easily have given him that part of the response from his subordinate’s conversation with the former journalist, as it would benefit him himself, knowing the truth, which actually contained word-for-word the content of the meeting, thanks to the latest eavesdropping technology (with which the leaders of the prosecution organ had been equipped).

Something similar happened to the chief prosecutor himself when he froze for several minutes after hearing the eavesdropping, his gaze glued to the tape recorder like a pea, driven by curiosity to see if anything else would come up next that would surprise him. But his anticipation turned out to be hollow. And under the pressure of this disappointment, the long-standing question nagged at him: what criteria had the personnel department taken into account when appointing Bardhi to the prosecution organ as a prosecutor, knowing that he completely lacked the severity and harshness of punishment, and during the investigation, never used the terrible pressure and fear; in fact, he saw the accused as a rational human being, not as an enemy, and was not guided by the intention to force him by all means to accept guilt and reveal what prompted him to commit the criminal act?!

Equipped with a gentle nature, much more humane for a prosecutor, Bardhi completely lacks ambition for a career (the very quality that every boss wants in their subordinates, as the absence of this trait relieves them from the anxious worry of being replaced and prevents them from stressing out and wasting extra energy trying to get rid of them).

After this reflection, the chief of the prosecution began to precisely determine the extent of the confession, how to formulate the response so that the chairman of the power believes that in the prosecutor’s office, nothing special was discussed, apart from casual conversation, mainly about literature. To illustrate his point, he would emphasize the fragment of the conversation where Prosecutor Bardhi asked the former radio journalist why only half of the long story was published in the magazine “Nëntori,” without the notation (to be continued), which is unusual for any magazine, accompanying it with the concrete addition: If it were a printing error, it would have been reflected on the corrections page.

In fact, there was no note on this page, and the other half of the story was not published in the subsequent issue! With this detailed explanation from the author about why this unpleasant anomaly occurred during the publication of the story, the chief prosecutor would feel completely relieved and convinced that he provided the required clarification.

– “According to you, just to ask about this issue, five with nothing, was the conversation trivial?”… – the chairman of the Executive Committee responded with open disbelief. – “Is this all you could gather from your subordinate’s response? If so, let me approach you in another way: should you believe that their conversation revolved around a question, which along with the answer, does not last more than a minute?”…

– “For the case in question, another detail should also be taken into account: my subordinate knows the former journalist from years ago, and he reads literary works with passion. From their complete conversation, it is clear that they had previously met randomly and exchanged thoughts on his literary work. Perhaps in an earlier meeting, Bardhi may have expressed to the former journalist his desire that when he gets the chance to stop by his office, they could talk freely and openly.

He also benefits from his state role as a prosecutor, which completely relieves him from the concerns of other officials who hesitate to meet a declassed individual. Therefore, I reiterate once again, with a thousand percent guarantee that, according to information from reliable sources, during their conversation, no legal issues were touched upon, apart from literature. This is for two reasons: firstly, Prosecutor Bardhi’s interest in literature is always at the center of his curiosity.

Secondly, the self-restraint of the conversationalist’s springs directly from the care to avoid touching upon and disturbing a fundamental issue that was personally addressed by the first secretary of the Party Committee. This convincing argument fully validates my opinion. But even if we assume for a moment that the former journalist directed a legally related question to Prosecutor Bardhi, I am a thousand percent sure that he did not respond, considering that this matter is handled by the top boss of the Party…!”

After these words, the same thing happened as last time: the phone signal was immediately cut off, and the chairman of the power slammed the receiver down angrily, accompanying his action with banal insults against the chief prosecutor. It was clear that the head of the prosecution spun whatever nonsense he pleased, using that part of the conversation that revealed nothing, to tell the head of power: “that’s how the conversation went between the former journalist and Prosecutor Bardhi.” In a desperate attempt to emerge unscathed from the difficult situation, the chief of prosecution thought it wise to ramble on about generalities, phrases that are commonly used, which neither harm his subordinates nor disrupt relationships between them.

This stance had solid support from the widely known fact of the energetic intervention of the first secretary, a significant liberal shift that fundamentally transformed the punishment of the former Radio journalist through bold decisions regarding shelter and employment, the two main pillars, restoring the fundamental civil rights that had been denied, which belittled him and forced him to walk with his head down due to the heavy burden of shame, as every hour and moment, he felt outside of society, as a devalued being.

Meanwhile, the chief prosecutor of the district found it unbelievable and absurd that a very important detail had escaped the attention of the great party chief; he had not sensed, or it hadn’t even crossed his mind, that against the fundamental “reforms,” an invisible barrier was being covertly prepared to restrain him by the chairman of the power, whom he cleverly and successfully used as a legal basis for the deportation of the former journalist for two years in military farms, where he would face great challenges.

In reality, the chairman of the Executive Committee remained patient; he was not swayed by the enticing provocation: before committing to fulfilling this aim, he carefully studied all the implications and consequences. And only when he was assured that the great party chief would not intervene with the head of the Military Branch to delay the call for military mobilization (with the undisputed explanation of the recruit’s age limit crossing), did he take steps towards concretizing, with unwavering confidence that this time he would emerge victorious with the clever maneuver of calling the soldiers, deeply satisfied that he would put the great party chief in his place, striking at his “Achilles’ heel!”/ Memorie.al

Continuation in the next issue

Copyright©“Memorie.al”

All rights to this material are exclusively and irrevocably owned by “Memorie.al”, in accordance with Law No. 35/2016 “On Author’s Rights and Related Rights”. It is strictly prohibited to copy, publish, distribute, or transfer this material without the authorization of “Memorie.al”; otherwise, any violator will be held liable under Article 179 of Law 35/2016.

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)