By Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Five

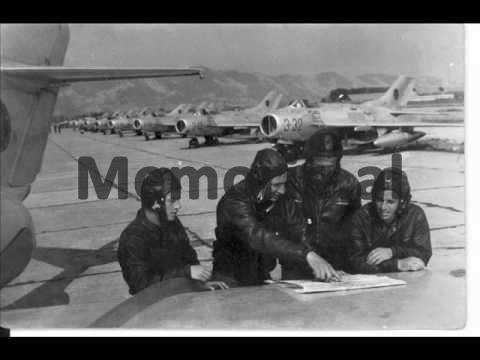

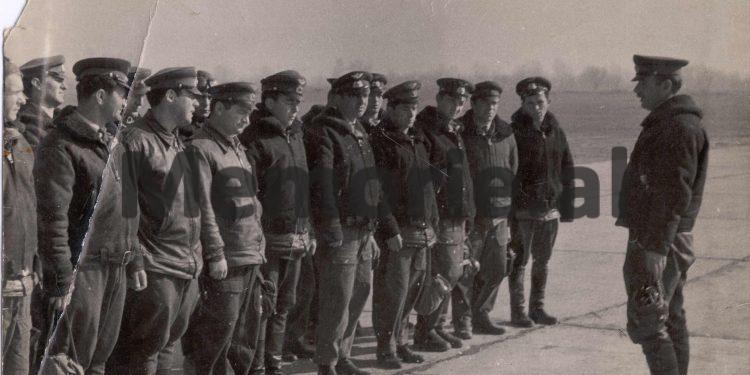

Memorie.al / Impressions and memories from the life of the talented pilot from Tragjas, Colonel of Aviation, Niko Selman Hoxha, who fell in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airport in Rinas during a combat exercise with the fighter jet ‘MIG’-17 F, in front of the regiment’s personnel and several military academic cadres. The impressions and memories have been gathered by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj in June – July 2012, in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, etc., during meetings with people and phone conversations, even reaching the distant Boston. Each meeting and conversation with contemporaries of Niko Hoxha and his relatives has found reflection in the material, with fidelity and authenticity. The monograph reflects only a part of the hero’s life, that part which is related to aviation and flight, and does not extend to other spheres of the multifaceted life of the man who propelled military and aerial discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, as he was disciplined, orderly, and very correct in the unit, was also distinguished for an exemplary regime in life. He did not live in the unit and did not eat in the quality canteen of the pilots but at home, thanks to the dedication and good management his wife, Jolanda, provided; his regime lacked nothing. This writing does not include Niko’s family life, nor does it touch upon his care for his sons, Valeri and Sasha, who he left still young, but whom he surrounded with great parental care and love while he was alive. Other writings that will follow will surely shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life, which in this monograph have remained somewhat in the shadows.

Author

Continues from the previous issue

The aircraft technician, retiree Ismail Harizaj, remembers this situation as follows: “In the command of the regiment, a one and a half-room apartment was allocated; it had to be shared. There were 25 officers and employees who had requested housing. It was quite difficult for the command of the regiment to allocate this contingent. Niko Hoxha knocked on every family of those who had made requests. To see, up close, how the officers and their families lived. He even came to my house. He saw my grown sister and asked me, ‘Who is this?’ I replied, ‘This is my sister; I am responsible for her.’

He approached the pot with food that was boiling, lifted the lid, and asked my wife, ‘What have you made for Ismail to eat?’ This survey the commander conducted in every family. The houses were allocated, and it was decided that I would take that living space. I was happy, and the other family members were happy too. Finally, we would breathe a little easier. In the meeting where the command’s decision was announced, someone among the needy, like me, reacted against it, and with spirit, I gave him the right. Niko listened, thought for a moment, and said: ‘When your son sleeps with his wife, you might cover your head so you don’t see it, but Ismail’s sister cannot do that.’ This argument convinced the complaining officer, and after that, he did not say anything more.”

It happened that some planes had defects. We worked long hours to fix the issues without going home, not even to eat. Niko stayed there with us until the technical defect was resolved. To make it easier for us technicians and specialists who were working, he would send the unit’s vehicle from house to house to bring us food. Perhaps for that person, who had the highest regard for people as well as accountability for the execution of tasks, the designation of ‘humane, strict’ suited him well.

The colonel observed situations with correctness and was rigorous in the decisions he made. When it came to enforcing military regulations and technical standards, Niko Hoxha did not spare anyone. When he was seated, you could talk to him freely, like a friend; however, as soon as he stood up, he transformed into an authoritarian, and you could communicate with him only with ‘yes, sir!’ or ‘how do you command?’ using the language of regulations.

Retiree Pajtim Elmazi, who served his mandatory military service in the Rinas regiment from 1962 to 1965 and knew the colonel from the perspective of a soldier, recalls: “One Monday, like on any other day of the week, the regiment was under review. The commander inspected personally, moving from subunit to subunit. When he came in front of me, he ordered: ‘soldier (he didn’t know my name), two steps forward!’ I mentioned my surname, presented myself saluting, and complied with his order, stepping forward two steps in front of my comrades. The orders from the colonel were endless; ‘Get in position!’ was the next command.

I followed the command again and the colonel saw my white collar. I noticed a slight satisfaction in his eyes. Then he gave me the order to take off my left shoe and then to open my backpack. He saw and found all my individual equipment in order, and he was pleased that I was compliant with the discipline regulations, and right then he gave the order to my commander: ‘Send the soldier for seven days’ leave to his family!’ I was surprised, but I caught the sharp response from my commander: ‘as you command, comrade regiment commander!’ This event warmed me and made me happy. I don’t know why I thought I had made arrangements with the colonel; I went to my family and returned in time. But fortune didn’t favor me in another instance. They don’t say without reason that the pear tree has its stem at the back. Not long after, the colonel came for the evening call, which we made every night. The assembly took place.

I, along with some friends, had gone to watch a movie in the neighboring unit. When my name was called, I wasn’t there. “Bring them to me,” ordered the colonel, and we found ourselves in front of him, as if caught in the act. He recognized me and ordered my commander: “Give him seven days of disciplinary detention.” They took away my hat, my belt, the laces of my shoes, and took me to the isolation room, which was located in the guard house. I had to sleep on some planks, without a mattress or a blanket. It was my first time, and I couldn’t fall asleep. After midnight, the colonel came, found me awake, and asked: “Why aren’t you sleeping?” I didn’t answer but showed with my head the conditions. He ordered the guard officer to take me to my sleeping area, to my bed. I learned a lot from both situations. Commander Niko, as he himself implemented the regulations, expected that his subordinates would do the same.

With Niko Hoxha, no one could compromise on the regulations. For Niko Hoxha, the motto of work was: “Do as I do, and let’s do it together.” Hypocrisy and servility were unknown to the colonel, as was work just for show. He had distaste for boastful individuals and “empty-headed bosses.” Veteran pilot Haki Jupasi from Starja e Kolonjës, when speaking about Niko’s strictness regarding military and technical discipline recalls: “In relations within the unit, you could communicate with Niko only with: ‘yes, sir’ and ‘as you command.’ In social settings, he would become your closest friend. With his endless stories, Niko became the center of conversation.

I clearly remember when the colonel would come in the afternoons to the unit to play volleyball, a sport he loved very much. The commander was tall and agile. He loved to spike the ball, and his forearm would rise above the net when he prepared to strike. He liked to have Kosta Dede, Anastas Ngjela, Sulo Gorica, and other tall players on his team. The colonel also played football. In Valias, where he lived with his family, he was part of the town team and played against the State Farm team of Kamza. During games, he was very correct and humble, and you couldn’t distinguish him from the other players. I also remember him gathering corn, which had been planted by the regiment’s auxiliary economy, mingling among the officers and soldiers.

Niko Hoxha had a wide circle of friends everywhere, but you would never see him sitting in clubs, at a table with a drink for hours like others. The colonel was neither a gossip nor a drinker. With him, “the food had salt, and the salt was just right.” As veteran aviator Osman Bozhiqi recalls: “I worked with Niko Hoxha in the same unit and at the same aerodrome, but we didn’t have closeness. Military hierarchy distanced us. However, you had Niko in your family, both in joys and in unfortunate times. He didn’t notice if he visited the family of a soldier, a worker, a sergeant, a petty officer, or higher up. To him, everyone was equal. He was there for everyone and helped with all his heart.”

Osmani further emphasized: “When he found you at fault, Niko Hoxha never yelled at you in public but would call you into his office to tell you directly what he needed to say and hold you accountable. He treated everyone fairly.” Colonel Niko Hoxha had a special habit that others did not practice. On festive days and during celebrations, he would invite various distinguished cadres to his home, of course, for lunch or dinner together. This practice not only brought him closer to people but also allowed them to relieve the tension and stress they experienced all the time in the regiment. This was thanks to the environment that Niko Hoxha created for his guests.

On the occasion of New Year 1960, Commander Niko invited to his home in “Stalin City” two young officers, pilot Kapo Selmanaj and technician Xhevair Shega. Xhevair remembers this rare event in his life: “Niko came out to the door of the house and greeted us with a sincere smile. He was dressed in civilian clothes. We liked to see him in military uniform because it suited his athletic build. Throughout lunch, he created a joyful and cheerful atmosphere. He was quite pleasant. He joked with Kapo, whom he knew personally. To ensure I didn’t feel sidelined, Niko maintained the balance himself. Since I am from Kuç, and he had been in my village during the war when he was a partisan, he joked with me as well and had a delightful sense of humor with us young people.”

On another occasion, when he became the commander of the aviation regiment in Rinas, the Colonel invited two of the most distinguished pilots of the year to lunch at his home. It was January 1, 1964. That day, luck was with pilots Anastas Ngjela and Çobo Skënderi. Here’s how Çobo Skënderi recalls that day: “Lunch was served at his home in Valias. No one did this. I had been a leader in the aviation units, but I had not done this. That day, at the lunch prepared by Colonel Niko Hoxha, his father-in-law, General Spiro Moisiu, former commander of the General Staff of the Albanian National Liberation Army, was also present.”

Niko Hoxha, with his wisdom and broad spirit, was like a “balsam” that healed everyone’s wounds. Niko’s wise and sweet words, spoken in a pure Lab dialect, did not let the “wounds” of those under him or those simply near him fester but healed and improved them. That person did not easily throw away words. The colonel’s words were “binding,” not “biting.” In June 1964, as I was taking off in a pair formation, in the capacity of the formation commander, at the Rinas aerodrome, with the aircraft ‘MIG’-17 F, with side number 227, I interrupted the takeoff and, as a result of clumsy actions to reduce speed, ended up in a drainage canal at the end of the safety zone, along with the plane I was piloting. Fortunately, the extraordinary incident did not end in disaster.

As later analyses showed, my limited experience as a pilot and inadequate preparation for that flying task allowed me to make serious mistakes that almost cost me my life. I stayed in the hospital for a month and then took another month of leave at the Army Convalescence Center. After this rehabilitative activity, I returned to the unit. At that time, I was single and living in a hotel. One day the colonel came to my room and found me there alone. As military discipline required and as was part of my upbringing, I stood up and greeted my “guest.” I was surprised and delighted by Commander Niko’s behavior. With a sweet smile and very social tone, he said to me: “Njazi, I’m glad to see you healthy!”

I perked up, emerging from the emotional state caused by the arrival of that “human giant,” and as if caught in the act, I returned his greeting. From the way he addressed me and greeted me, the colonel made it clear that he wasn’t angry with me and held no grudge, even though I had severely damaged a plane, the repair of which required 10 days and nights of intensive work from the regiment’s engineering and technical forces, under his direction. For these and other rare qualities that the colonel exhibited daily and continuously, Niko Hoxha was loved and respected by all who knew him. Let us express this sentiment with the words of a simple specialist who has worked closely under Commander Niko’s leadership in the “Stalin City” regiment. Osmani, in a conversation with early friends, told me: “Niko Hoxha was a commendable man. He was crafted by God with all that is good. With people like him, you could even throw yourself into the fire, if needed.”

Having heard it, I cannot keep to myself a very humane action by the commander of the “Stalin City” regiment, Niko Hoxha, during the distant ‘50s of the last century. What I will tell you relates to the colonel’s care and human affection for his subordinates, regardless of whether they were pilots, technicians, specialists, or others working alongside him. This early incident is told by some as a lived experience, while others prefer to recount it as a joke. Their work doesn’t concern me. What I want to emphasize strongly is the immense human spirit and love that man had for people. At that time, many cadres of various profiles were at an optimal age to start families, but not everyone had luck smiling at them.

A young pilot, successful in his duties and very charming in appearance, was in a dilemma and had not “succeeded” easily in forming a serious bond with any girl. Of course, his profession and social position meant that our charming young man had high standards regarding the qualities of the girl he wanted to marry. However, the groom candidate, in all honesty, was not without flaws. He was curly-haired and had a “bald” head. When girls saw him with a hat on, they approached and befriended him, but when they saw him without a hat—let’s put it in popular terms, when they saw him “bald”—they distanced themselves from him as if he had an infectious disease. This was a big problem for our colleague. He had made several attempts, but they had all turned out “empty.”

The issue was not only with him; the entire staff of the “Stalin City” regiment felt it, and the colonel was worried as well. Commander Niko thought deeply about the situation and found a solution. He summoned the single pilot to his office and said: “You will take leave, go wherever you want, and return when you have finished your duties, but I want to see you back in the regiment, with a bride.” The officer followed the commander’s orders and found a bride. In this case, as always, the colonel judged and acted like a good parent. It is likely that many years later, when another generation has passed and Niko’s generation, along with us, his students are no longer alive, our stories will be told, like folk tales and anecdotes.

A brief biography, who was Colonel Niko Selman Hoxha?

I mentioned from the very beginning that I am not a biographer and that I find it quite difficult to put into writing all the things that need to be said about that giant of Albanian aviation. Relatives, contemporaries of Niko, and ordinary people who lived near him have offered invaluable help in this endeavor. We can say that without a brief biographical description of the hero and his life, this modest “monograph” would necessarily be incomplete. I began my “journey” for this work from Vlorë, the birthplace of our hero. Completely by chance, in mid-June of this year, I went on vacation and settled in the home of Niko Hoxha’s granddaughter, the sixty-year-old Nurhan.

A rare name, quite meaningful and unusual at the same time. She is the daughter of Sinan Xhuveli from Tragjas in Vlorë. Her mother was the colonel’s cousin; however, since she grew up in the home of Selman Hoxha, Niko treated her like a sister.

Nurhan was delighted when she found out that I had been a pilot and told me things I did not know about the childhood and adolescence of our hero, whom she always referred to as “uncle.” The noble Lab woman moved and impressed me deeply when she disclosed a secret she had kept with fervor. Her story is about a promise her mother made before leaving this life: “If you meet Nikos’s friends, her mother had said, you will keep them in the palm of your hand.”

This is an essential obligation for Nurhan, but also a great responsibility for me, as I have decided to write something about the colonel. I needed this motivation to get started, and it came to me unexpectedly. In the following days, I hurriedly wrote something about the hero and read it to the noble Lab woman, her husband Bardhoshi, and their twenty-year-old son, Olti. As I read that part of the writing in the presence of my three young friends, I noticed that Nurhan became “all ears,” while Bardhoshi seemed somewhat detached but not uninterested. The same cannot be said for their son, who had only heard about his mother’s uncle. I promised that Capedane woman I would expedite the writing dedicated to her uncle and that I would definitely send her a copy./Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue