From Ali and Aziza Shamil Baku, Azerbaijan

Memorie.al / Ismail Fark (Ismayl Ferk) was born on April 20, 1933, in the city of Shkodër, Albania, into the family of Siuri Zubeydi Bajramit, from which the lawyer Rubejzi Abadini Farka also came, and he was an only child. In 1938, his family moved to the city of Tirana. After the death of his father in 1943 (he was killed during World War II), his grandmother, Renni Fark, took care of the family. In Tirana, Ismail Fark completed his secondary education (high school), graduating in 1949, and together with other young Albanians, he began studies in Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) at the “Technical Academy.”

During his studies, he married Markarita Dyomina (Margarita Diomina), whose parents were killed during World War II and were declared martyrs. In 1955, Ismail graduated from the university, and a year later, he became a father to a daughter. In June 1956, he returned to Albania with his daughter and wife, Margarita Diomina. After working for two months at the Wood Processing Plant in Elbasan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs selected Ismail and sent him to the State University of Tirana to continue studies in the fields of Linguistics and European Studies, which he completed in 1960. He was then assigned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to work in France, where he served for 10 months. On May 2, 1961, Ismail Farku was sent to the Embassy in Moscow as a referent for technical engineering issues, while his wife and daughter remained in Tirana.

However, the time when he began working in Moscow coincided with the deterioration of relations between the Soviet Union and Albania. Soviet KGB officials asked Ismail Farku to work secretly for the Soviets, which he informed the Albanian embassy about. In response, the ambassador at the time, to divert the attention of the KGB officials, sent Farku to the consular administration of Albania in Odessa on December 23, 1961, but after two days, he brought him back. As a diplomat and pursuant to the rights of the Albanian state’s relations with the Soviets, Farku awaited the ticket and departed by train towards Moscow.

At midnight, the bellboy knocked on the door and asked to be let in. Suddenly, Ismail Farku saw three people enter the room, demanding to see his passport. As he lowered his head to give them his bag, he felt a strong blow to the back of his neck. Later, when he regained consciousness, he found himself in Botkin Hospital in Moscow, with one side of his body paralyzed. He asked the doctors for the bag containing his documents but was informed that when he was brought to the hospital, he had no bag with him and that the only paper found on him was a document without markings or seals from the Technical-Scientific Society, in the name of Mehdi Mehdijev Shemsedin. Thus, according to this document, he was taken as an Azerbaijani, Mehdi Mehdijev Shemsedin.

Immediately, Ismail Fark informed the Albanian embassy in Moscow about his situation, from where two people came and informed the hospital director that he was Albanian. The embassy specialist, Idriz Shehu, visited the hospital and monitored his health condition. On December 12, 1962, the Albanian embassy in Moscow closed, and the staff left, leaving only three people for the final matters, among whom was also Idriz Shehu. During this period, Ismail Fark’s health improved, and in May 1963, he was discharged from the hospital. Idriz Shehu, who was by his side, contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (BRSS) where Ismail Fark was also sent. After hearing his account, they informed him that those who had attacked him were not from the KGB, but thieves trying to hide what the KGB had actually done.

They subsequently discussed with the Bulgarian embassy about the possibility of organizing his return to Albania through Bulgaria. There, Ismail Fark was asked to describe the incident for the preparation of documents and to provide them with his account. He wrote everything that happened to him in Albanian, while the Bulgarian embassy provided two documents: one allowing him to stay in a hotel in Moscow, and the other a document confirming that Ismail Fark was of Albanian nationality. Thus, while staying at the “Kiyev” hotel in Moscow, he was informed by the Bulgarian embassy that his documents were ready for his return to Albania.

However, unfortunately for him, Ismail Fark did not know that the KGB was at the helm of organizing his departure from Moscow. On November 16, 1963, a policeman knocked on the door of Ismail Fark’s room and forcibly took him to the police station. There, at midnight, unfounded accusations were raised against him for “false” activities, claiming that he was the Soviet citizen, Mehdi Mehdijev Shemsedin, who, under the name of the Albanian citizen Ismail Farku, was attempting to leave the country using his identity!!!

The KGB officer, Butirskin, imprisoned him, where Ismail Fark, contesting the injustice, went on a hunger strike. Subsequently, he was placed in a solitary confinement cell for 12 days where, starving, his legs swelled, and tragically, he lost consciousness. From there, Ismail Farku, now labeled “Serbski,” was sent for trial. The court sent his case for psychiatric examination to the Institute of Psychiatric and General Justice, where exactly the daughter of Felix Dzerzhinsky (who laid the foundations of the KGB), General Markarita Feliksovna Talce, diagnosed him with “Schizophrenia” and declared him “a dangerous person to society.”

Based on this medical report, the People’s Court of the region decided to send Ismail Fark for forced “treatment” in a Psychiatric Hospital. On April 27, 1964, accompanied by two medical guards, he was brought to Baku, where he was initially placed in Psychiatric Hospital No. 2 and after five days, he was transferred to Psychiatric Hospital No. 1. Therefore, everything was done to keep Ismail Farku hidden in a remote area.

Throughout this time, everywhere, in prisons and psychiatric hospitals, Farku maintained a stance against the Soviet regime while associating with individuals who had sacrificed in the fight for human rights. In conversations with them and through learning from their experiences, he became a dissident himself. Even though Ismail Farku told the doctors that he was Albanian and not the Azerbaijani Mehdi Mehdijev Shemsedin, no one believed him anymore. Moreover, they took the document from the university where he had studied in Moscow, ensuring that no one was registered there under his real name.

Meanwhile, the news that Mehdi Mehdijev Shemsedin was hospitalized reached his parents who lived in the Kasem Ismailov region (now Goranboj) in Azerbaijan, who had long considered their son lost. On May 25, 1964, they went to the hospital in Baku, but instead of seeing their son Mehdi Mehdiyev Semsedin, who was tall at 1.80 m, had completed only four grades of school, and spoke no language other than Azerbaijani Turkish, they confronted another person, Ismail Fark, who was only 1.64 m tall and spoke Albanian, Russian, and French, as well as being knowledgeable in Persian and Arabic. Thus, these parents realized that this stranger was not their son. They did not have a way to know the truth that their son had been taken by the KGB.

Later, KGB and Ministry of Internal Affairs employees in Azerbaijan met with Ismail Fark in the hospital, explaining that the road to escape from there was to accept Soviet citizenship. If he accepted, they would release him from the hospital and help him live there. However, Ismail Farku refused again, and thus, the oppressive doctors administered “elderly treatment,” subjecting him to inhumane methods, including the removal of his teeth, just to prevent him from declaring his Albanian nationality, forcing him to hide under another name. For Farku, medications such as Trizidol, Kaloperidol, Sulfazine, etc., were used in large doses, but despite the pressure, he never accepted Soviet citizenship.

After 25 years of suffering, two KGB employees informed Farku that with the new wind of ‘Glasnost’ from Gorbachev and with Perestroika, Russian society had embarked on the path of democratization. They planned for Farku, considering his health condition, to write a letter to Gorbachev’s wife, asking for forgiveness. Thus, while in the hospital, individuals from the Azerbaijani Red Cross and the “Red Crescent Society” met with Ismail Fark and ultimately changed his pavilion from psychiatric to mental health issues!

In this pavilion, the doctor treating him, Ejup Aliyev, with good intentions aimed at eliminating what was said about Ismail Farku, directed a letter to the Technical Academy in Saint Petersburg, inquiring whether the Albanian Ismail Farku had studied there in the 1950s. Perhaps due to the changes occurring in the Soviet Union, or because those responsible for his plight had been dismissed, the response he received stated: “Ismail Farku studied at this university.” Upon receiving Farku’s old file from the university, Doctor Aliyev noticed that the name of Ismail Farku was not recorded in the file located in the hospital, so he replaced it with the new document and informed the hospital administration that, “Ismail Fark is regular.”

Alongside Ismail Farku in the psychiatric hospital was the Azerbaijani dissident, Nadir Agayev, who took advantage of the dissolution of the Soviet Union to escape from the hospital. Later, in 1990, he published the book “The Hidden Magic of the Sahani,” concerning the prisons in psychiatric hospitals, where he also mentioned Ismail Farku. This book was published in Russian and Azerbaijani Turkish in the newspaper “Karatelnaya Meditsina” in Moscow, drawing the attention of society, as well as foreign newspapers, information agencies, and diplomatic entities that showed interest in the painful fate of Ismail Farku. Even the foreign radio, “Svoboda,” which broadcasts in Russian and Azerbaijani, presented Ismail Farku’s heartbreaking story through readings of the book. Thus, ultimately, with the help of Nadir Alayev, on August 9, 1990, Farku was released from prison and returned home.

From this moment forward, the search for Ismail Farku’s relatives began by the International Red Cross Committee, while the chairman of the branch on “increased searches,” M. Sheynberker, offered assistance from Munich, requesting the International Society for Human Rights to notify about Ismail Farku. Meanwhile, in 1992, the Albanian embassy opened in Moscow, and Nadir Alayev sent the details regarding Ismail Farku there.

However, the bitter story for this man did not end there, as it was learned that in Albania, believing him to be deceased for years, his wife had started a new family, his daughter had grown up and had her own family, and his son, born in 1962, was also married, with all living in Tirana. Thus, Ambassador Hasanmataj informed Ismail Farku that it would be more sensible for him to live in Azerbaijan.

Today, Ismail Farku lives in the outskirts of Baku, near the city of Shuvalan, in a private home where he works at whatever comes to hand to make a living, while his political foreign status remains unknown…!

Discoverer of the Rare Story!

Translator Entela Muço, an employee at the General Directorate of State Archives and a specialist in the Ottoman language, met Ali Shamil, an employee at the National Academy of Sciences (Institute of Folklore, Department of International Relations) in Azerbaijan and his wife Aziza, at the 15th Congress of Turkish History in Ankara in 2006. She later encountered them again at the 1st International Congress of Turkish Medical History in Konya in 2008.

“But I got to know them better in the summer of 2008 in Baku, where I went to conduct research on the role played by ‘The Afshars of Iran’ in the history of Iran and Turkey, located in what is now called Southern Azerbaijan. Ali Shamil, from the very beginning, showed willingness to contribute to the recognition of Albanian figures who have contributed to the social life of Azerbaijan. But it was a mutual desire to provide respective contributions to the painful history of both countries. There, Ali Shamil introduced me not only to the fate of Ismail Farku but also to the lives of many other Albanians, and fulfilling his desire, he brings to the Albanian reader the life and role that Albanians have played in Azerbaijani society,” she explains.

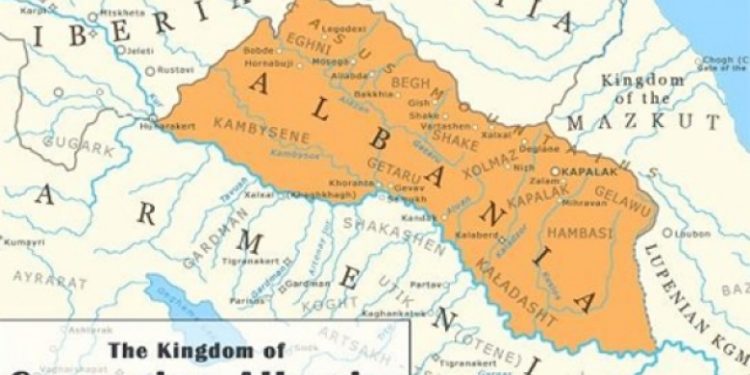

The Albanian State of the Caucasus

While today there is a state called Albania, in ancient times, there was also a state with the same name in the Caucasus, often referred to as “the Albanian state of the Caucasus.” From the 4th century BC until the 8th century AD (the time of the Arab conquest of the Caucasus), the borders of this state included the region from the north to the shores of the Caspian Sea, in the Greater Caucasus mountains and up to the city of Derbend, from the west to the Kabr river and from the south the Lesser Caucasus mountains to the Araz river. Nowadays, between this 1200-year-old state and present-day Albania, apart from the name, it is impossible to find other connections. In the place of the ancient Albania of the Caucasus, the Republic of Azerbaijan has been established. Even if there is no common origin link between the inhabitants living in Albania and those in Azerbaijan, there are some ties with the shared name, although at different historical times. Therefore, I thought to present a few articles regarding Azerbaijan-Albania relations.

In 1998, I received an invitation from the National Democratic Foundation of Azerbaijan for Human Rights regarding political dissenters against the Soviet regime and the preparation of articles for Azerbaijani dissidents to include in the upcoming International Encyclopedia “The Dissenters’ Dictionary,” to be published in Poland by the UN. For this global publication, we included in the political list 50 Azerbaijani dissenters, among them was one Albanian, Ismail Farku, who was forced to live and suffer in Azerbaijan. This is the article in the International Encyclopedia “The Dissenters’ Dictionary,” which is offered today to the Albanian reader./Memorie.al

Prepared by Entela Muço