From Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Four

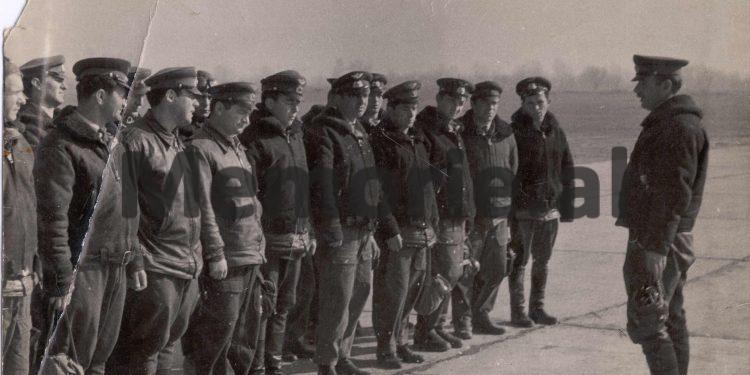

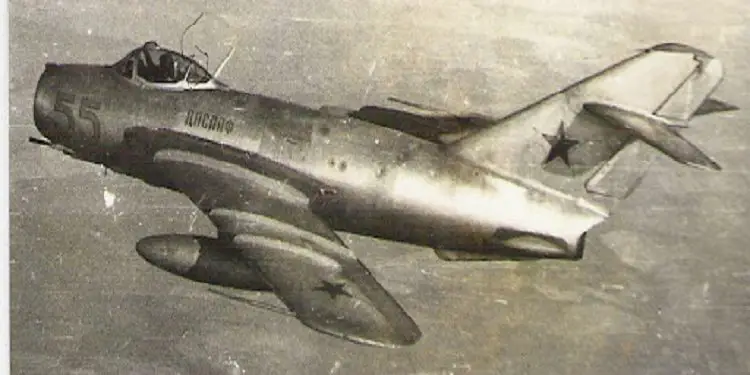

Memorie.al / Impressions and memories from the life of the talented pilot from Tragjas, Colonel of Aviation, Niko Selman Hoxha, who tragically fell in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airport of Rinas during a combat exercise with a MIG-17 F jet, in front of the regiment’s personnel and several military academy cadets. The impressions and memories have been gathered by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj, in June – July 2012, in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, etc., through meetings with people and phone conversations, even reaching distant Boston. Each meeting and conversation with contemporaries of Niko Hoxha and his relatives has been faithfully and authentically reflected in the material. The monograph reflects only a part of the hero’s life, that part related to aviation and flying, and does not extend into other spheres of the multifaceted life of the man who drove military and aerial discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, being orderly, disciplined, and extremely correct, was also distinguished by an exemplary regime in life. He did not live in the unit and did not eat at the quality mess of pilots, but at home; thanks to the dedication and good management of the situation by his wife, Jolanda, he lacked nothing. This article does not include Niko’s family life, nor does it touch on his care for his sons, Valerin and Sashën, whom he left still young, but whom he surrounded with great parental care and love while he was alive. Other writings that will follow will surely shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life that have remained somewhat in the shadows in this monograph.

Author

Continued from the previous issue

Here I express a somewhat advanced opinion. Niko Hoxha, by performing his next act of bravery, passed the “test of fire” when he took to the air with a jet airplane fueled with gasoline produced in Albanian factories. Victory in this case was measured by the increase in the autonomy of our aviation. Flights would no longer depend on fuel imports from the Soviet Union; planes would take to the air thanks to the high quality of our fuel, which was also safer.

The initiative and perseverance of the commander for the qualification of pilots holds great value on its own. Perhaps we would not have first-class pilots in Albania without the presence of these values, which were embodied in our brave colonel. Two groups of pilots were scheduled and completed flights to obtain the first-class military pilot qualification. One of the groups of pilots that received this qualification was in “Stalin” City, and the other at the challenging airport in Rinas. It is not a coincidence that, in both cases, Commander Niko was the regimental commander. After him, even though the leading personnel of the units were at advanced levels and the qualities of the pilots had somewhat improved, no one took the initiative to organize flights for the first-class pilot qualification.

The fall of the colonel, in the line of duty and at a mature age, hindered and greatly harmed the efforts for pilot qualification. A pilot or a group of pilots embarks on the difficult path of professional qualification when they see themselves inspired by giants like Niko Hoxha, in whom bravery, courage, initiative, perseverance, determination, and especially leading by personal example are deeply intertwined. When these qualities are combined with the rare organizational and leadership skills that were present in the colonel, then achievements are assured and pilot qualification steadily increases.

Niko Hoxha, with his confidence in the youth, involved in the qualification group to master the sophisticated ‘MIG’-19 PM plane, newly graduated pilots from aviation school, such as Guri Merkaj, Agron Daci, Besnik Shahi, and Andrea Toli. The difficulty of this task lay in the fact that they did not have the required number of flight hours to transition to more modern aircraft. Commander Niko Hoxha was not only a friend of the pilots; he also respected, appreciated, and stood by the technicians, specialists, and soldiers, sharing their concerns and helping them overcome difficulties without arrogance or pretense.

Aviation technician and retiree Sulo Gorica, one of the technicians who extensively operated the modern ‘MIG’-19 PM aircraft, and who was also the technician for the airplane with which the colonel often flew, told me in a phone conversation: “… Niko would arrive at the airport quickly, even before we had opened the planes. He would find us working and jokingly say, ‘haven’t you opened the airplanes yet, you sleepheads?!’ He would decide to fly that day and organize the work to fulfill the day’s tasks. He smoked a lot. He liked the ‘Partizani’ cigarettes, among the more expensive ones. When we took breaks, he would call me over, and I would approach him nervously, but he would relieve my anxiety by telling me interesting stories and events with humor, in a calm manner and with clean language. We both smoked and talked like good friends.”

In the same “chord” was aviation engineer and retiree Xhevair Shega. “When we were at ‘start,’ waiting our turn for night flights, or awaiting an improvement in weather conditions – Xhevair recalls – Niko would stay with the aviation technicians and specialists, in the first area, engaging in free and interesting conversations with us and treating us as equals.” There are countless episodes recounted by people who worked and lived during the time of Niko Hoxha or were close to him. Even from this simple fact, I reach the conclusion that Colonel Niko Hoxha, through his work and behavior, became a point of reference, or as veteran aviation pilot Çobo Skënderi told me: “Niko Hoxha was the fate of Albanian aviation.”

This is the reason that made me feel overwhelmed in selecting all those “pearls” I heard during those days while collecting materials about the colonel. Who to choose and who to leave out? One story is more beautiful than the other; indeed, the “pearls” are all equally beautiful. I was greatly impressed by the long and fact-filled account of Osman Bozhiqi, an aviation specialist, who remembers himself, throughout his life, with a screwdriver in hand, asking the pilots who landed from the air about the technical condition of their aircraft. Osman has had impaired hearing for a long time. The roars of the jet engines he operated for a long time may have contributed to this issue.

To talk and communicate clearly, we used a quiet café without clients or noise in Tiranë e Re. Among many facts, Osman underlined: “The colonel had respect for people. He would criticize you to fulfill tasks, not for personal matters, and he gave everyone what was due to them. Niko Hoxha was a shining example in every aspect. Niko respected both pilots and technicians alike. He, as a pilot, flew with all the ‘MIG’-15 Bis aircraft available to the regiment (referring to the fleet of aircraft the aviation regiment had in “Stalin City” from 1954 to 1961) and did not have a specific aircraft; whatever he knew himself, Niko shared wholeheartedly with all the other pilots.

When Niko Hoxha was the commander in “Stalin City,” there were flights during the day, at night, in clouds, and in all weather conditions. The regiment roared with the noise of the airplanes and the work of the people on the ground. The entire airport was bustling and humming, like a beehive. When I say that Niko Hoxha “took the hand” of Albanian aviation, this conclusion is not unfounded. If I had the ability and practical opportunity to “sew” together all the stories and memories of the aviators I met and talked to these days, they would surely justify this conclusion.

Gëzdar Veipi, one of the most skilled pilots of Albanian aviation, admired Niko Hoxha greatly and considered him a role model (perhaps more than anyone else). Reflecting on their joint work, he told me: “… He followed the training step by step. Niko had the ability to grasp the problem and make decisions quickly, at the right time. His theoretical level was good; he stood out above his colleagues…”! The same thing was told to me by retired pilot Serafin Shegani, one of the longest-serving pilots on the supersonic aircraft ‘MiG’-19. In attempting to portray the combat qualities of the colonel, Serafini, speaking in refined literary Albanian with a characteristic Pogradec accent, pointed out:

“Without Niko’s contributions, there would not have been the development of Albanian aviation. A notable characteristic of Niko Hoxha was his leadership at all times and everywhere by personal example…! He was at the forefront of flight operations. Niko desired and made it happen to be part of the combat formations where tactical air missions were determined. He wanted to fly all types of aircraft that the regiment had. No one could surpass Niko Hoxha.” Without even saying it, the seriousness with which the commander valued air missions, which were the most challenging and delicate, is evident. Our beloved colonel had great pride.

Colonel Niko Hoxha was a person of broad culture and demonstrated rare organizational and leadership abilities. Adding to this were his courage and initiative, which combined together, placed him at the forefront of tasks and in the lead during various situations. Niko Hoxha was also quite a good methodologist. He led Albanian aviation through several difficult and delicate stages. At the dawn of the 1950s, Colonel Niko (at that time holding the rank of Major in aviation) began the work of organizing and completing the first aviation unit in Laprakë. He gathered a squadron of “assembled” pilots and integrated them into a process of air training based on scientific knowledge. With difficulty, the colonel facilitated the transition of these pilots to lightweight propeller-driven aircraft of the ‘JAK’-9 P model, which, to be fair, was quite temperamental, especially during landings.

When the reactive flying technology ‘MIG’-15 Bis arrived in our country, the colonel had to lead another not-so-easy action. The pilots and technicians had to master the use of this new technology, both on the ground and in the air, which was previously unknown. The new ‘MIG’-15 Bis model posed challenges due to the advanced technology upon which it was based. The colonel was entrusted with establishing the first aviation regiment equipped with jet aircraft. Organizing and leading a new regiment, comprised of pilots, technicians, and specialists from various schools and levels returning from Yugoslavia and arriving from the Soviet Union, some of whom had issues, was not easy for him. Later, it also fell to the colonel to bear the burden of coping with the blockade enforced by the Soviets, which had a strong impact on aviation.

In those difficult conditions, Niko Hoxha was at the helm of efforts to bring modern, supersonic aircraft equipped with sophisticated weaponry, the ‘MIG’-19 PM, to Albania for the first time. Retired pilot Roland Sofroni, who led several transition groups on the MIG-19 S models, though somewhat reserved in offering opinions due to his health condition, when it came to remembering the colonel, said: “Niko Hoxha, as a commander, gave you what you deserved. He didn’t take away your rights. Niko had quite good theoretical and tactical knowledge. When he dissected and explained tactical maneuvers and elements of flight, he was precise. As a flight leader, Niko Hoxha was excellent and calm. He was also a very good methodologist.”

Initiative, courage, and the bravery of pilots are essential elements that determine the success of a flight. The colonel embodied these qualities to the fullest and, being such, he not only performed difficult air tasks successfully but on occasions, risking himself, challenged adverse weather conditions and emerged victorious. Pilot Çobo Skënderi recounted an instance of this nature: “One night – Çobo tells – the Rinas regiment was flying. It was dark, and horizontal visibility was quite poor. Enver Hoxha called Beqir Balluku (then Minister of Defense) and asked: ‘Who is flying tonight?’ ‘Rinasi is flying,’ replied Beqir Balluku. Then Enver Hoxha continued: ‘Go out on the balcony, with eyes open – you see, and then close your eyes – still you see.’ ‘This Niko Hoxha knows,’ replied the Minister of Defense. Enver interjected: ‘He must be exceptional!’ And Beqiri responded: ‘that’s right, comrade commander’!” (Enver Hoxha was the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces).

Such was the colonel, unique and distinct from others. This advantage of his was recognized and acknowledged even at the highest levels of the Albanian Party and state leadership. Niko Hoxha was a legendary leader, born to be at the forefront, not trailing behind in situations. The colonel was brave and loved and respected brave men. As a military man, Commander Niko was quite orderly, strict, just, and calm. Some specific techniques of piloting, which were challenging to implement, he would test himself in the air before assigning them to his subordinates. This applied to the landing of the aircraft from the fourth turn, with the engine turned off.

One of the pilots, who had carefully observed this maneuver of the commander and had noticed the “trick,” one day dared to ask him: “Comrade Colonel, why do you come to the fourth turn at an altitude of 900 meters with a deep profile, while we come at 400 meters with a normal profile?” The commander looked at me thoughtfully and responded to my question: “And then?” Taking advantage of the fact that he was seated, I found the courage to speak: “You come down with the engine off!” I had struck a nerve. Niko immediately reacted, friendly – Çobo Skënderi added – “The regulations have it, others (pilots from other countries) do it; why shouldn’t we Albanians try it?”

We can say without fear of being wrong that the colonel sacrificed and risked himself, trying out new maneuvers first before teaching those under him. Commander Niko Hoxha was a brave pilot and had a great sense of pride; he could have been killed by his pride for keeping his word. Veteran Koço Andoni, one of the pioneers of Albanian aviation, when I spoke with him, at a time and place unsuitable for his age and health (on the road, walking, in the mid-summer heat of July), after recounting many good qualities of Niko Hoxha as a pilot and commander, emphasized:

“On that day (referring to the day of the extraordinary incident), there was no need for Niko to take the shot himself. Any designated pilot could successfully execute the shot, but he, being proud, wanted to turn into action what he had told the officers of the Military Academy.” There is no end to the praises for our colonel, the hero in love with the sky, Niko Selman Hoxha. Those who take the effort to read this writing will understand me better and feel that I could not write everything that my friends told me and all that my heart urged me to express. I am sure that many others, lovers of aviation and admirers of the legacy left by the colonel, with “finer pens” will fill in the gaps I have left in this regard.

However, I have some unspoken truths that I have not conveyed: Niko Hoxha – the man. As a wise saying from our people goes: “The dessert comes at the end.” In other words, Niko Hoxha was a man; not a god. I add, without worry that I will be criticized, that the colonel was a human being, not annoying. The humanity of that man was evident in every step and throughout his life. The commander sacrificed himself to help others. The colonel knew well, not only the pilots, for whom he nurtured immense love and care, but also other cadres, soldiers, civilian employees, and anyone who was close to him.

As a good psychologist, Niko Hoxha had the ability to penetrate the world of his subordinates and their worries, actively engaging in resolving their issues. He was kind-hearted and compassionate. A soldier from the North of the country was isolated from his peers, feeling sad, thoughtful, and often distracted. As Gezard Veipi recounts, the colonel noticed this and, with wisdom, naturally approached the young man, sat down next to him as if by chance, and started a casual conversation, as Niko knew how to engage in dialogue. The soldier opened his heart to the commander and shared the reason for his distress. The twenty-year-old had fallen in love with a girl from his village, but their families did not approve of the marriage of the two lovers.

The next day, the colonel took the soldier in the regiment’s car, and together they traveled to the mountains. He met with the families of the young couple and others, whose voices were respected in the village, reached an agreement, left the soldier with his family for a few days, and returned to the unit joyful. After a few days, the soldier returned from leave “transformed.” Is this the only instance of such kindness? Niko Hoxha “weighed” the troubles of people on the scales of sound logic and with the heart of a compassionate parent.

In the 1960s, in the aviation regiment of “Stalin City,” a difficult situation arose regarding the accommodation of officers’ families and the regiment’s employees. The regiment was new, and the personnel making it up were young. Many of them had recently married and were seeking housing. During those years, it was “fashionable” to house families in shared entrances. In these cases, two families would take one room and share the kitchen. The command of the regiment was in great distress, wondering whom to displace and whom to assist. They were all in need./Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue