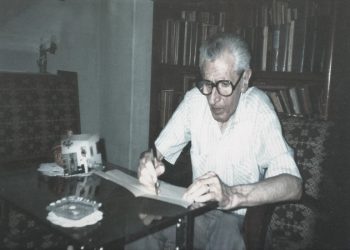

By Piro Milkani

Memorie.al / Just as we were finishing the filming of “Victory over Death”, Kadare released his second novel, titled “The Wedding”. It came after “The General of the Dead Army”, which had already begun to be translated into several foreign languages. The film “Victory over Death” was highly anticipated by both audiences and official critics alike. For this very reason, at a national ceremony, alongside awards for artistic works in various genres, Peçi Dado, Gëzim Erëbarë, Feim Ibrahimi, and I were awarded the “Republic Prize”. The film’s musical theme became so popular that it served as the opening and closing jingle for programs on the only Albanian state television (RTSH) for many years.

The music was composed by Feim Ibrahimi, who had just graduated from the High Institute of Arts, specializing in music. I was beginning my new career as a director. Thanks to this film, after a phone call from the highest offices of the Party to the head of the neighborhood, I finally received authorization for a modest apartment at the end of December 1967.

It was a one-room apartment with a kitchen in the newly built Block 202, at the end of “Mine Peza” Street. I had waited for this apartment for seven years, since the day I returned from my studies, after four years of engagement to the pianist Margarita Kristidhi, or Bebi, as everyone called her. That year also marked the publication of Kadare’s novel “The Wedding”.

Meanwhile, I was searching for a script for my second film. For example, “The Wedding” could have been a novel adaptable for a film script, but alas! Ksenofon Dilo, a painter at Kinostudio, who also wrote interesting articles for the newspaper “Drita”, had decided to try adapting “The Wedding” into a film script.

Even worse, Dhimitër Anagnosti, in search of his second film as a director, had already struck a deal with Dilo. He would be the one to make “The Wedding”…! As if the praises from the important offices of the Central Committee of the Party weren’t enough, or the glowing reviews in the political and literary newspapers and magazines of the time, we were informed that the next evening, at the Writers’ and Artists’ Club, there would be a detailed discussion about the novel “The Wedding”. The hall was packed.

In the presidium were Kadare, Fadil Paçrami, the secretary for culture in the Party Committee of Tirana, the Chairman of the Writers’ Union, Dhimitër Shuteriqi, and others. One after another, the discussants highlighted the values, innovations, metaphors, and interesting characters of the novel. And just when no one expected it, Bilal Xhaferri stepped up to the podium. A well-known writer who had also sparked interest among us filmmakers.

He addressed Kadare and the novel with heavy criticism, particularly regarding the chapters where he treats—or rather distorts—the Kanun, this ancient constitution that has regulated human relations for centuries in the deep regions of Albania. There was no applause from the audience. Silence and tension. Quietly, he returned to his seat, somewhere in the third row. Fadil Paçrami broke the silence.

– “You there,” Fadili spoke, without mentioning Bilal’s name, “leave the hall immediately. You are unwelcome here.” And so it happened. Bilal left, head bowed. The solemn meeting dissolved. How Bilal’s life unfolded after this would require a separate chapter. A few days later, in the courtyard of Kinostudio, I met Ksenofon. Anxiously, he informed me that Anagnosti had changed his mind.

He no longer wanted to be part of the new film that Ksenofon was finishing, titled “Why Does This Drum Beat?” (Not “The Wedding”, nor “A Strange Wedding”, nor “The Skin of the Drum”, nor “The Wedding and the Ghost”, as the British later called it in the radio dramatization they produced for Kadare’s work on BBC London).

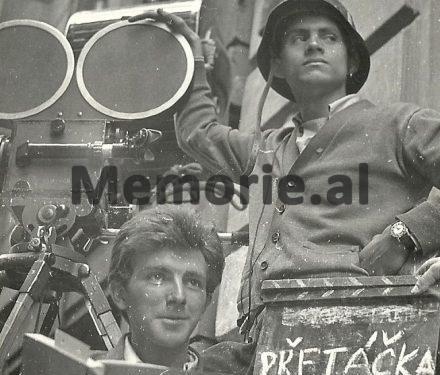

Ksenofon proposed that we work together on this. I didn’t hesitate long and accepted. The director of Kinostudio, Vaskë Aristidhi, approved this change. For Kadare, it was his second novel; for me, it was my second film.

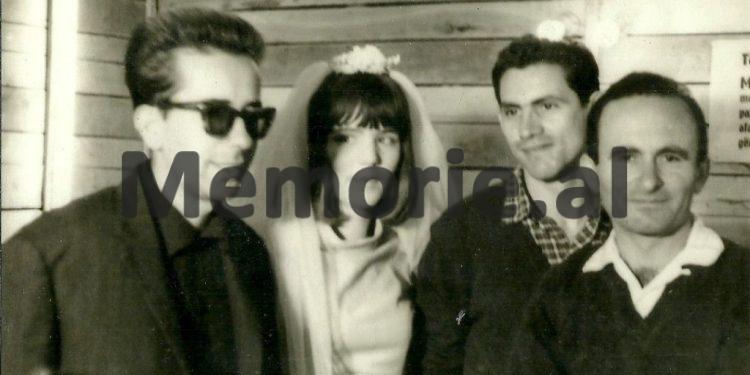

It was February 1968. The film team was formed, and preparatory work began. On the first Saturday of March (even Saturdays were workdays), I took leave from the director. I was getting married. After four long years of engagement, waiting for an apartment. A so-called wedding.

My parents came from Korça, along with my father’s cousin, Todi Gjata; my older brother, Berti, a submarine officer in Pasha Liman, with his wife, Marieta. My other brother, Vaska, had been transferred to Tirana a year earlier as a scientific researcher at the Institute of Linguistics and was living with us.

Only relatives living in Tirana attended. On Saturday evening, we visited the Kristidhi family. Originally from Macedonia, they had settled in Albania in the 1930s. Besides Aneta and her husband, Genc, there were also some friends of the Kristidhi family. Congratulations for our marriage were accompanied by a glass of raki and some chocolates. That was all. A few hours later, the bride’s family came to visit us. Even the few chairs we had weren’t enough for everyone.

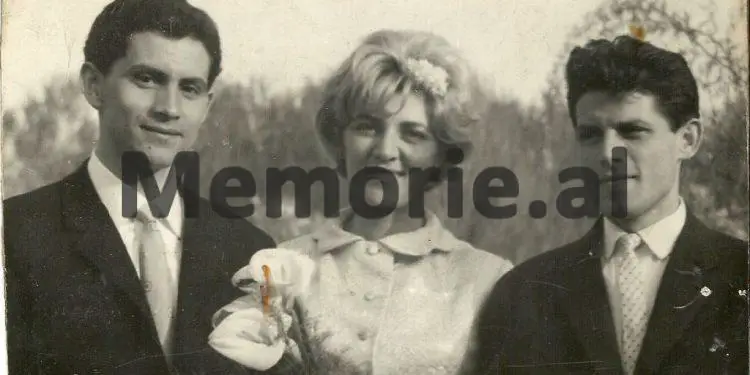

The next day, Sunday, April 7th, we went to pick up the bride. We stepped into the courtyard of the villa and took some photos. Bebi was more beautiful than ever. She didn’t want to wear a wedding dress, even though, up to that point, there was no official order prohibiting such attire.

She had decided this herself. The white jacket and skirt were custom-made from a beautiful and expensive fabric sent by Uncle Joni, a gynecologist in Thessaloniki. Two taxis we had ordered took us to the Hills of Tirana, near the Church of Saint Prokop, to take a few more photos.

We slept in the 3.2 by 3.7-meter bedroom, while the others stayed in the kitchen with the annex. On Monday, the “honeymoon” began. In the seven-seater Gaz van from Kinostudio, besides Bebi and me, who sat in the front seat, Ksenofon, Todi, Petraq, and the assistant director, Fehmi Hoshafi, also joined. When we arrived in Fier, those of us in the back seats had stiff necks because the side seats of the Soviet Gaz, designed for war, were uncomfortable.

The next day, the “honeymoon” included visiting and photographing the modern Nitrogen Fertilizer Plant, the city’s power plant, and the barracks of the volunteers working on the Fier-Vlorë railway in Mbrostar. Volunteers, both men and women, had come from all over Albania. We photographed them, hoping to find potential actors for the upcoming film among them.

In Mbrostar, even though I knew the novel by heart, I ran into an old friend who had once studied with me in Czechoslovakia. His name was Agim Pirdeni, and he was a representative of the Central Committee of Youth, overseeing the railway construction. My curiosity was piqued by how the mountain girls, who at this age had left their homes and villages for the first time, were adapting to their new environment.

– “What can I say, Piro? They absorb everything with curiosity. They are just as amazed as we were back then, when we traveled by ship, crossed half of Europe by train, and were left speechless by the magic of Prague. For example, in the evening, we set up a large screen in that square over there, and they sit on the ground to watch a movie for the first time.

Do you understand? For the first time. We let them react during the screening, but when the movie ends, in groups, curiously, they approach the screen, and after a while, they peek behind it. They don’t understand where all those people who were on the screen moments ago have disappeared.”

The expedition to scout filming locations and, possibly, find actors from the Fier Theater or visits to Berat, to the Textile Combine there, lasted eight days. We returned to Tirana. Early in the morning, I hopped on my bicycle to go to Kinostudio, while Bebi, a little later, also on her bicycle, went to the Institute of Arts. In the afternoon, we met again at home.

I was the first to tell her how my colleagues had welcomed and congratulated me. Then Bebi shared her story. She had received the same congratulations from her colleagues and students. But around 11:00 AM, the director of the Institute informed the music department about an urgent meeting. The topic of the meeting: “A serious disciplinary violation by Margarita Kristidhi Milkani!” What had she done?… She had returned to work two days late. The rules were clear: only five days of leave were granted for marriage.

A serious breach of work discipline. What would happen to her? Demotion, re-education, or…?! It largely depended on how she herself would react. Specifically, how she understood this mistake and how she would self-criticize. She stood up and spoke very briefly: – “I understand the mistake and accept it. But honestly, I didn’t know that marriage leave was only for five days. So, I promise you: if I ever get married again, I won’t repeat this mistake.” The room burst into laughter.

“He escaped only with a warning and a two-day salary deduction for the two days of delay. After writing the technical-directorial script, the film crew, a total of 37 people, plus 18 actors, settled in Fier. For the main role, that of Xhavit, I had entrusted 19-year-old Timo Flloko, while the role of Katrina was won by Adelina Xhafa, a graduate of the polytechnic.

For the role of Katrina’s father, I chose the renowned baritone Lukë Kaçaj, and as the scientific collaborator, Fehmi Hoshafi. Bert Minga, freshly graduated from the acting department, not only excelled in the role of the journalist but also found time to fall in love with one of the five ‘mountain girls,’ Katrina’s friends.

With Irena. Thanks to this film, from Bert and Irena’s marriage, Aulona was born. Meanwhile, I was awaiting the birth of my first son, Eno. When the film was completed, after passing all the filters of the time—artistic council, commissions from the Ministry of Culture and the Party Committee, and screenings by the Kinostudio collective—it also successfully passed the most challenging test: its viewing in the ‘Block’ by the head of propaganda, Ramiz Alia. Even Kadare was not disappointed. – ‘It is the strangest film of the Third World.'”

He was clearly making fun of Mao Zedong’s theory, which divided the world into three parts (as if it were a big cake): the capitalist world, the revisionist world (the Soviet Union and its satellites in Eastern Europe) and the Third World (China in the first place, the non-aligned countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America and, of course, Albania).

The film laboratory, at Kinostudio, urgently produced 26 copies of the film that were distributed throughout the Republic. The press was also not expecting it badly. Pleasure. On that very day, when I accompanied my wife to the maternity ward to give birth, at the Autotractor Plant, the country’s Prime Minister, Mehmet Shehu, was talking to the workers about how work was going with the production of the first Albanian tractor.

And at that very moment, a worker, a member of the Workers’ Control group (such control groups had arisen in every enterprise in the country), asked his prime minister if he had had a chance to watch the new film, which was being shown in all cinemas in Albania. When he told him that he had not seen it yet, the worker told him that the film contained some serious ideological displays that contradicted the Party’s orientations.

– “What are these shows?” – Asked the prime minister – “Well, in that film, there is a wedding scene in a barracks for volunteers on the Fier-Vlora railway. That highlander marries an editor and the film crew, without fail, dresses that bride in a veil. Aren’t these shows of the bourgeois mentality?”

After thinking for a moment, the prime minister said to him: – “Why are you sitting idly by? Go to the Kinostudio there and show them how films are made.” The news spread like wildfire through the city. In all the newspapers of the time, in the cultural section, there were aggravating articles.

The most diligent journalist turned out to be the one from the newspaper “Luftëtari”, M. Shehu’s name was. In addition to the opinion of the workers of the Combine, he also added some other “thagmas” about the foreign shows in the film. My wife, Margarita, had a difficult birth with Enon.

So the doctors advised her to stay in the maternity ward for a few more days. My world had turned upside down. And yet, every day I went to the maternity wards sidewalk to see her and our common creation. In the fourth-floor window, a happy Baby appeared with little Eno. I had to play “happy father.” There were no newspapers or the latest news from the market in the maternity ward.

One day, as I was leaving the maternity ward, a spring rain started. I walked casually, my feet taking me towards the city center. A man with an umbrella approached me and put my head under it. The next day, in the lobby of the Kinostudio, they came, the workers’ control of the Autotractor Combine.

An icy meeting with me. They told me that they wanted to watch the film again. We were prepared for this. The film had been set up in advance in the gears of the projection machine, in the small projection room. During the screening, there was a dead silence. When the lights in the room were turned on, he, the most skillful of them all, spoke first.

I have long forgotten their names, but I still remember his name. His name was Harilla. – “How is it possible, my friend Piro, that you could make such mistakes”? Irritated beyond belief, I tried to explain to them that the dress of the highlander Katrinë was not a wedding dress, but a light gray piece of terital, a product of the Textile Combine. That that small piece was not a veil at all, but a piece of white tulle.

That throughout the film, Katrina and her friends was dressed in overalls. How could we do it? Marry her in overalls? Shouldn’t it have been a little different, the one who was marrying Xhavit? Nothing convinced them. They left almost angrily. It was Sunday. Walking like bewildered people through the streets of Tirana, we remembered what Kadare used to tell us:

“They don’t have it with you. They have it with me. They knock on the door, so the door can hear. Trust me”! Believe me, believe me, we will eat it. We passed the “Rinia Park” diagonally. That Sunday in March, there was a scorching sun. Or maybe that’s how it seemed to us. The time on the city’s big clock marked 14:30. And there he was. Sitting on a bench.

It was Dhimitër Tutulani. The brother of the martyrs of Berat, Margarita and Kristaq Tutulani. A controversial guy. An incurable talker. He didn’t take long, but he met us with the first ones. – “Hey, you. Why are you wandering around in vain? Or are you pretending that you don’t know anything”?! – “What do I know”? – Xenophon asked.

– “That, that meeting that will be held tomorrow at the Palace of Culture… tomorrow afternoon at five o’clock, there will be a big meeting for you. They will criticize you, then you will criticize yourself in vain, but the decision has been made anyway. You will go for re-education in the bosom of the working class. Get out now, you is disturbing my peace”! What about this black spot! Where does this fool know these things?…

“The impact of the film indirectly affected him as well, the Secretary of the Central Committee and member of the Political Bureau. He went directly to the office of the great one, Enver Hoxha, and complained that Comrade Mehmet was interfering in the affairs of his sector. Enver Hoxha agreed with him. – ‘There’s nothing we can do. That’s just how he is. Sometimes he gets carried away. But you, continue with your work!’/ Memorie.al