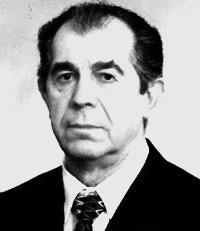

By Sulo GOZHINA

Memorie.al / Whenever January 27 approaches each year, the mind turns to the day of the Holocaust, to World War II, the victims of which included 6 million Jews. Unlike other countries, Albania offered shelter and protection to the Jews. During the war, over 600 men, women, and children arrived in Berat. Writing about this people, both as much as they have suffered and as noble as they are, requires much time, work, effort, and sweat. The broad scope of this subject shows that every time you sit down to research, just as many new details and previously unpublished stories emerge. This topic has also been addressed in the last two decades by the well-known publicist and researcher from Berat, Simon Vrusho. For his valuable work to date, as well as for new discoveries in this field, we conducted this interview.

Mr. Vrusho, over the last 20 years, you have written and published extensively about the Jewish presence in Berat—books, articles, studies, reports, portraits, etc. Indeed, in several writings and interviews on this interesting yet vital topic for the Jews, almost from the medieval period to the time before and after World War II and beyond, references have been made to you. But even when it seems that this topic has been exhausted or depleted, you still unexpectedly bring forth, discover, and publish new facts, documents, and details. My question is: what has been the latest discovery regarding this topic?

The latest discovery is Miki, a Jew with trays in hand, sheltered during the Holocaust in Berat (1942-‘45) at the home of Vangjel Buda, among the Budas, generations of jewelers, likely of Jewish descent, renowned jewelers also known for their icon work in engraving, casting, and embellishment…! Vangjeli died young, in 1968, at the age of 50…! Devoted to jewelry, books, and the “Voice of America”…! He died with the “Voice of America” at his ear…!

He passed his profession of jewelry on to his son Dhimitri (Taqo), who has passed it down to his sons, Gavril and Valirian…! Miki was kept as a household son until 1945, when Vangjel Buda escorted him to Durrës, where other Jews had gathered, returning to the countries they had emigrated from…! Nasho Qytyku, 81 years old, a neighbor of the Budas, remembers Miki, as they were of the same age and played together in the streets of “Vakëfi”…!

It seems that the number of Jewish tourists, Israelis, is increasing in the city of Berat. They are interested in the presence of their ancestors in this city, the traces, the testimonies, the echoes?

When they hear or see that the Jews had a neighborhood of their own, a neighborhood located in the center of Berat, from an urban perspective (between the Lead Mosque and the Metropolitan Church), where the street is named “JEWS,” and when they learn that the Jewish community had its rights recognized and protected, when they had representatives in the city administration, when they had their synagogue, they surely feel good…!

But they were not centered only from an urban point of view, but also economically and financially, as their community or trade Jews financed and supported the local economy during difficult times…!

They were also at the center from a cultural aspect, as their representatives actively participated in literary contests and competitions organized in the city, where the local elite would take part…! From the beginning of the 1500s, the Jewish neighborhood had 11 families, and after a few decades, it grew to 25 families and later reached 100 families…!

In these circumstances, we formed a legitimate hatred against the communists. When we parted ways, I was appointed as a teacher in the Mat district (he, a year later, in Dukagjin). I gave him a poem of two sonnets that I had dedicated to him, as well as to some other friends. The title was: “Towards the Galleries of Arbënie’s Future,” which he changed immediately to: “Towards the Catacombs of Arbënie’s Future,” as if to anticipate the storm that would befall the homeland. He wrote: “Questo è il mio dramma che pianger’ mi fa.” (This is my drama that makes me cry). Along with many other poems, the catacomb sonnets were also burned. I only remember the first stanza and some lines extracted:

“In your eyes, I saw the trail of thought,

The damp regret for the world that has passed,

The sorrow that brutally killed the spirit and the heart,

Left no feeling in the heart but despair!”

At that time, Pjetri wrote satirical poetry. He had a rare talent. His writings flowed in a strange harmony of satire. Time erased all of them. Arbnori left us a great spiritual legacy in several fields: the theoretical and practical path of his politics for building democracy, his literary work, which was characterized as “an exemplary coherence of humanity and artistry” of his life, and above all, the platform of efforts in extraordinary circumstances, not only to resist oppression, not only to confront it but also to defeat evil, dishonor, deformity, and the hell of dictatorship, which he called “The Struggle to Remain Human,” a struggle in which there were many distinguished fighters, and Arbnori was one of the most distinguished.

He referred to his secret diary kept during those long years of imprisonment, written in a special code, for the deciphering of which he continued to work before death betrayed him.

“Consciously – he wrote in his book ‘The Young Martyrs in Albania’ – I chose a path that led me to a long imprisonment. “To remain human – he continues – is not some great bravery, but a duty. Yet it has not been easy to fight to build a shelter without leaving another out in the rain; to secure a piece of bread without taking it from another’s mouth; to strive to be educated without leaving a friend in darkness; to struggle in chains to enlighten my own captivity without burdening the life of the friend next to me. In extremely difficult conditions, I consider it an achievement that I survived without humiliation and have the opportunity to look my friends, acquaintances, and enemies in the eye!”

I think it is worthwhile to briefly mention, just two words about the “foundation” of the family education where Pjetri was raised, since I do not know if anyone has ever spoken about this. His father, Filip Toma, an officer in the Albanian gendarmerie, known for three “nos” – “Not corrupt, without supporters, without a home,” was killed fighting valiantly against the communists in 1942 after having also fought on April 7, 1939, against the Italian occupation. On April 5, 1939, he handed his four-year-old son, Pjetri, a nagant and helped him pull the trigger, because the heir of the Albanian Kingdom had been born. Nevertheless, this man with three “nos” had left his son a rich library.

His mother, Gjystina or “Dyta,” as we called her in the neighborhood, was a more stoic and determined mother in her role as a parent; I have never known anyone like her in my life. She greatly influenced her son’s education. Pjetri recalls some principles of this mother, who shone with dignity for the resistance she showed against the reprisals of the communist regime, and which he tried to follow:

“To rely on faith in God.

To maintain the pride of the family.

To approach work with diligence and perseverance.

To not complain to anyone about my troubles.

To never feel morally ashamed.

To not touch the world’s goods.

To never betray friends or strangers.

To not become a servant of anyone.

To never lose my sense of humor, even in difficult conditions.

Without becoming a coward, to be a resistor.”

As for Arbnori’s political stances after the fall of the dictatorship, I will not speak. They are well known by all: balanced in the chaotic imbalance of Albanian politics during these years of transition; restrained and cool-headed in the face of rampant provocations; steadfast without the slightest compromise in his struggle for democracy and integrative processes towards European and Euro-Atlantic structures, with hope and full confidence in a better future for Albania.

He remained loyal to the politics and the party he joined from the beginning, but the politics abandoned him, just as it had abandoned other true democrats, replacing them with “katovicas,” skilled masters tasked with obstructing and bewildering democracy. During this time, we were far from each other because I had come to America. I called him very rarely. I didn’t want to disturb him, but I followed his life step by step through people from my family and friends. He had allied himself with the so-called democrats, who were only working to hinder democratic developments and who betrayed him. One day I could no longer endure it, and worried, I called him.

With a voice like that of a stranger, he replied: “There’s talk of an appointment at the embassy in the Vatican, but so far, I have received no official notification; however, I continue to work within the ‘Alcide de Gasperi’ Institute (an institute that dealt with political studies, which he himself directed) and, as always, I continue to write!”

They say he was “tired.” Indeed, but had he been there in Brussels to represent Albania, his voice would have been heard more than that of anyone else. Truly, Europe had included him in the “International Biographical Dictionary”; “for his outstanding contribution to remaining human”; in the “Dictionary of International Biographies”; “in honor of his distinguished contribution to human rights”; Europe had awarded him a “Certificate of Merit recognized worldwide”; “for distinguished service, which is noted in volume XXVI of the “Dictionary of International Biographies”; Europe had given him a “Certificate for recognition of outstanding achievements, which are recorded in publication XIII, ‘who are the international intellectuals”, and the title from the Parliamentary Assembly of French-Speaking Countries as “Grand Officer of the Order of Pleiades,” etc.; Europe would have accepted and honored him sooner than anyone else, just as it had accepted and honored him when Arbnori signed for Albania’s admission to its Council.

Arbnori had a high ideal for democracy. Perhaps he was one of the few who entered politics, understanding its essence, and maybe he understood it better than others. A significant influence, it seems, was the translation of “The History of England” by André Maurois, a translation he completed under the encouragement of the distinguished lawyer, who spent a significant part of his life in the Burrel prison, Engjëll Çoba, who told him; “You can learn from it—referring to the book History of England—more than from any other book circulating in Burrel Prison.”

Regarding his beliefs in democracy, Pjetri wrote: “If other people’s cannot follow this example point by point, the History of England should teach one side to rid their minds of ‘revenge at all costs’ and the other side, that they will be winners for a long time if they are tolerant and make reasonable compromises, perfecting democracy every day!”

His literary work, which holds great cognitive, artistic, and educational value, is quite extensive and has not yet been fully published. From 1992 to 2000, the following were published: the novels “The Shadows of the Middle Ages,” “The White and the Black,” “The Half-Built House,” “The Whirlwind,” “Brajtoni, a Distant Lightning”; the novellas “When the Vikings Swarmed,” “The Beautiful One with the Shadow,” “The Unknown – The Death of ‘Goebbels’.” He has also published the historical study “From Life in Communist Prisons,” the epistolary “Letter from Prison,” a collection of interviews “The Struggle to Remain Human,” “Pjetër Arbnori – Writer, Politician, Man,” a collection of memories, speeches, and journalistic articles “The Young Martyrs in Albania”; in German, memories about the German priest, Dom Alfons Tracki; “I Survived and Wrote,” translations: “The History of England” by André Maurois and “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,” translated from French.

This is not the place to analyze the literary values of these works, but I would like to draw attention to three things. First: Arbnori is part of the excellent trio of literature developed in prisons: alongside Trebeshina of the fires of hell and Zhiti of the stars of the sky. This literature encompasses unmatched artistic, cognitive, and educational values.

In the preface of the monograph; “Pjetër Arbnori – Writer,” by the foreign researcher, Giuseppe Gradilone, Lazër Stani wrote: “The writer Pjetër Arbnori is among those Albanian creators, who, while living in extraordinary conditions, made no compromises with the official scheme of socialist realism and created that Albanian literature which can be categorized as ‘the other literature.’”

Unfortunately, critical studies are generally absent today. Works are praised to the point of disgust that, instead of literature, contain propaganda and superficiality; but which possess extraordinary harmful anti-values, especially for the younger generation, in understanding the art of words and the realization of artistic mastery, often even in the realm of civic morality.

Secondly, Arbnori wrote during a time of absence of freedom during the years of dictatorship, years burdened by dictatorial bondage, not only for Pjetri and his political prisoner friends but for our entire nation. We all suffered the lack of freedom, especially those of us who were aware of what was happening under that anti-national and anti-people regime of crime. The most basic and humane desire for a person — freedom — led Arbnori towards literature as a creative spiritual necessity, as a goal, as a means, and as a support to realize it for himself, for the people, and for his homeland. Arbnori created in his consciousness a broad conceptual space for freedom.

He wrote: “For the intellectual, and not just for the intellectual, life is an effort to expand the boundaries of freedom every day, to open the windows of contact with the world, with reality when you cannot break the boundaries that surround you. There is also another way to enter the world of freedom, which is arduous but more effective: expanding freedom within you, in your mind and spirit. This is achieved through serious intellectual work, through thinking, discussion, and writing.”

Gradilone characterized this high spiritual phenomenon as “the arduous victory, and precisely for this reason valuable, of internal freedom, where one feels the need for the contemplations of great souls, like Saint Augustine and Severinus Boethius.”

Thirdly; in an interview he gave me as the editor of “Dielli,” Pjetri said: “In politics, people are quickly forgotten. I try not to be remembered negatively. In literature, some people are remembered longer. I wish that future generations, if they happen to remember me, will not say that I deceived them, misled them, or wrote with resentment.”

After this prolonged period of spiritual crisis passes, after this sick climate of our culture is healed, and after true democracy triumphs in our country, which Arbnori desired, hoped for, and worked towards, the conditions for reading and studying his literary work will be created, and the new generations will reflect and understand who spoke the truth about what happened in our homeland during the years of dictatorship — the Arbnoris, the Trebeshinas, or the endless flood of the pens of socialist realism, no matter how powerful they were in the realm of artistic mastery.

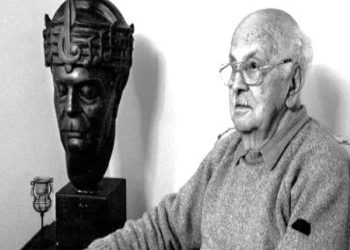

Our people should take pride in having produced, in one of the most difficult periods of its history, the shameful history of the fratricidal war among Albanian brothers, for the sake of an even more disgraceful ideology, for the sake of a bloodied dictatorial throne, such a personality as Arbnori. The struggle to overthrow communism and build democracy brought forth in Europe great political and spiritual leaders: in Poland, a Lech Wałęsa; in Czechoslovakia, a Václav Havel; and in Albania, a Pjetër Arbnori.

With the untimely death of Rugova and Arbnori, Kosovo and Albania lost — at a time when they needed them most — two distinguished personalities, cherished by their people and appreciated by Europe and the whole world: the Great Gandhist Ibrahim Rugova and the anti-communist ‘Tribune of Democracy,’ Pjetër Arbnori; but they will experience their immortality in the national consciousness and will be present for all generations of Albanians in the pantheon of illustrious personalities that our nation has produced./Memorie.al