By Qerim LITA

Part Three

– The Migration of Albanians in the Years 1912-1939 and the Reaction of the Albanian State –

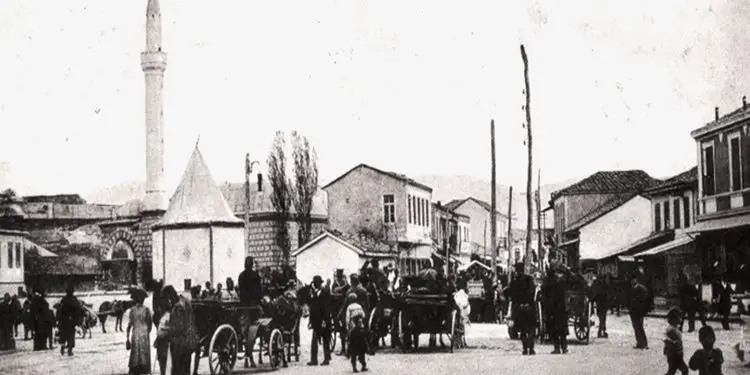

Memorie.al / With the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the withdrawal of the Ottoman Empire, and the occupation of Albanian lands by the Balkan Orthodox alliance, the process of migration of the Albanian population from their ethnic territories to the Republic of Turkey resumed. Recently uncovered documents shed light on the fact that within the year 1912-‘13, the occupying Serbian-Montenegrin and Greek armies forcibly expelled over 200,000 Albanians, the majority of whom settled in Istanbul, Anatolia, and other regions of Turkey. According to a calculation made by the Albanian Legation in Ankara, in 1928 there were 27,000 to 30,000 Albanian families in Turkey, displaced from Kosovo, Eastern regions, and Çameri, including those Albanians who had emigrated after 1913.

From the above, it is clear that with the exception of some regions in the eastern part of present-day Macedonia, where, as is known, the Muslim inhabitants belonged to Turkish nationality (Turk-Juruk), all other regions were populated by Albanian population. Sources from the police and military provenance of Yugoslavia indicate that the official Belgrade was not satisfied with the signed Convention, demanding that it include the exchange of populations, specifically the expulsion of another 100,000 Albanians to Turkey and the settlement of Orthodox elements from Turkey in Yugoslavia.

However, these figures did not satisfy the appetites of Serbian nationalists, as according to them, the expulsion of 400,000 Albanians did not fulfill “their Serbian state and national interests,” which was “the expulsion to the last Albanian” from their ethnic lands and colonization with Serb and Montenegrin elements, since the total number of Albanians under their occupation reached approximately 732,000 inhabitants. Based on this, they planned to sign a similar convention with the Royal Government of Albania, regarding the exchange of populations, specifically the expulsion of 100,000 Muslim Albanians to Albania and the bringing in of 100,000 Christian (Orthodox) Albanians, whom they considered “Serbs”.

For the realization of these anti-Albanian plans, the Yugoslav government envisioned the establishment of a Supreme Inspectorate, based in Skopje, with two regional centers: in Pristina and Peja. The establishment of this inspectorate was initiated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which in a report titled “Problems and Methods of the Migration of Albanians and Turks from Southern Serbia to Turkey,” drafted on October 23, 1938, emphasized among other things: “…In order for this heavy and delicate work for state and national interests to be carried out with minimal unrest, it is necessary that as soon as possible, in the month of January, the Supreme Inspectorate for the migration of Albanians and Turks to Asia be established, based in Skopje, which will have two regional centers: in Pristina and Peja…”.

Precisely these anti-Albanian projects prompted the Albanian elite in Kosovo and the Royal Government of Albania to take urgent measures to prevent their practical implementation. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, on August 5, 1938, communicated through a letter to its legation in Ankara that recently a delegation of Albanians led by Ferhat Beu Draga and Maliq Pehlivani had traveled to Istanbul. They had gone to Turkey to advocate with the “Turkish Government” that at least the previously signed Convention would not include Albanians. In this matter, Draga submitted a memorandum to the Turkish deputies, which included the perspectives of the Albanian elite under the occupation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Three days later, specifically on August 8, the Yugoslav Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a letter to the legation in Ankara, which had been forwarded by the Turkish deputy Sabri Beu from Istanbul to a friend of his in Belgrade, stating that “numerous protests from Yugoslavia” had been received. Certain individuals who had traveled to Ankara and Istanbul had delivered a long memorandum during their discussions with Turkish ministers, expressing their outrage against the fierce campaign of Yugoslav military-police circles against the Albanian population in Kosovo and its surroundings, aimed at forcing them to migrate to Turkey, even though the council for migration had not yet been officially established. Similar petitions were also submitted to members of the National Assembly.

Furthermore, this ministry announced on September 19, 1938, that the Government of the Albanian Kingdom had decided to send Mehmet Beu Konica to Ankara within a few days, with the aim of undertaking “an action with the Turkish Government” against the migration of Albanians from Yugoslavia to Turkey. According to an analysis prepared in November 1939 by the Yugoslav Ministry of Foreign Affairs, M. Konica had gone to Ankara at the order of King Zog, providing him with two specific tasks: “The first, it is stated in the Analysis, is of a general character, while the second concerns the Albanian minority. Mr. Konica was to act with the Turkish Government to ensure that during the implementation of the Migration Agreement, the Albanian population would not be accepted and to request the presence of an Albanian representative on the Migration Commission…”

Meanwhile, the Bulgarian envoy in Tirana, Pejev, on October 14, 1938, reported to Sofia about a meeting he had with the Turkish Minister of the Interior. During the discussion, the Turkish minister conveyed Ankara’s concerns regarding the accusations from official Tirana “against the Turkish Government concerning the establishment of the Turkish-Yugoslav Convention for the migration of 250,000 Muslims from Yugoslavia to Turkey…”

This agreement, it was further stated in the report, “is not based on solid ground,” because Turkey did not request from that convention to misuse the Albanian element in Yugoslavia but pursued a policy of “gathering its own – Turkish population,” as it was considered that in Yugoslavia there were at least “150,000 /instead of a maximum of 50,000 as evidenced by relevant Albanian factors/,” and if “these forecasts are proven unfounded and do not match reality, 250,000 would not be accepted, but less.” Furthermore, Pejev wrote about Ankara’s dissatisfaction regarding the alarm in Tirana, “which alarm and dissatisfaction have surpassed even Turkish kindness,” primarily due to semi-responsible Albanian personalities who, on the same issue, “presented memoranda” and highlighted “threats and accusations” against Turkey.

Regarding Mehmet Konica’s trip to Ankara, Pejev wrote that his interlocutor was convinced “of a warm reception for Konica,” but surely “he personally” would refrain from public efforts against the same Turkish-Yugoslav convention. At the end of the report, Pejev also informed about his meeting the day before with prominent Albanian deputies, who informed him that regarding the same agreement “some Kosovo deputies (for example, Jashar Erebara) had planned to discuss it in the respective parliamentary committees or to make an ‘interpellation’ regarding this danger for the Albanian element in Yugoslavia…”

As predicted by the Bulgarian diplomat, on November 16, 1938, the special committee elected by the General Assembly of the Albanian Parliament held an extraordinary meeting, during which the message from King Zog I was read on the occasion of the opening of the “Third Session of the Third Legislature of the Kingdom,” where the Turkish-Yugoslav Convention of Istanbul was explicitly opposed. After this, Albanian deputy from Dibra, Jashar beu Erebara, spoke in front of the attendees, calling for both the government and the people “to nurture the idea of the Albanian minorities” because, as he pointed out, a large number of Albanians live outside the Albanian State, who “should at least live as humans, have Albanian schools and not be marginalized…! They (the Serbs – Q.L.) work for their own benefit, as it suits them, and will exchange them as Turks, even though there may be Turks as well, but the majority are Albanians. Therefore, we should not remain asleep…!”

The scope of the State and the Albanian elite, alongside diplomatic efforts, also concentrated on internal activities which were carried out through various meetings and gatherings organized throughout the Albanian territories under Yugoslav occupation. The central theme of these meetings, as indicated by Yugoslav military and police reports, was to halt the migration of the Albanian population from their homes. The III Army in Skopje, in January 1938, reported to the High Command in Belgrade about a strong propaganda campaign taking place in Greater Dibra against the migration.

In a report prepared in June 1938 by the Information Department at the General Staff in Belgrade, dedicated to the activities of the Kosovo Committee, it was noted that former members of this committee: Maxhun Limani from Krasniqja, Sali Mani from the Malësia e Gjakovës, and Mehmet Alia from the village of Vllahnje, had recently held several meetings, in which they “convinced their circles that soon the regions in Kosovo, with the help of the great powers, would unite with Albania.” If the great powers “fail to convince Yugoslavia to give these regions to Albania,” then a plebiscite would be organized there, thereby finally realizing the long-standing demand of the Albanians for national unification.

Meanwhile, the commander of the III Army, Millan S. Jekmeniç from Skopje, informed the General Staff of the Army that Ferhat Draga had launched an action throughout the Albanian territory. According to his assessment, under the influence of Ferhat bej Draga’s action and international political developments, “Albanian propaganda in the South” had never been more vibrant.

The patriotic activity of Ferhat bej Draga and his associates is best described in the Analysis titled “Albanian Propaganda,” prepared on March 12, 1939, by the chief of the administrative unit in Skopje, Nik Dimitrijeviq. In it, among other things, it was stated that after the assassination of Hasan Prishtina, Albanian irredentism was led by Ferhat bej Draga, whose activities were “conducted through conspiratorial means.”

Visible signs of Draga’s action and his friends included “efforts for Albanians to gather in tight ranks, to select their representatives who would represent them in the National Assembly as well as their people at the head of municipal administrations.” Among his closest associates were teachers of religious education, imams, and officials of the waqf. In order for “the compactness to be as great as possible – it was further stated in the analysis – there has even been a reconciliation of blood feuds and other disputes from the Albanian elite.” The political activity of the Albanian National Movement encompassed two main points:

- The distribution of Albanian literature to the population, which was illegally infiltrating across the border;

- and the complete cessation of the migration of Albanians, whether to Turkey or to Albania. According to Dimitrijeviq, this activity of the Albanian elite, religious teachers, and Albanian diplomatic representations in Skopje, Bitola, and Belgrade had a decisive impact so that “the movement for migration, which had affected our Albanian population until 1936, is now stifled,” despite the fact that until that period, entire villages were ready to abandon their homes and leave their properties without any compensation “only for the state to relieve them from land taxation, to provide them with free passports, and to pay for their travel to our border.” Neither “the strict agrarian measures nor the confiscation of armaments” were successful, thus the only way for this issue to start from the initial point is: “migration through the designated diplomatic route according to the convention signed with Turkey, even though Albanians publicly say that they will not leave their homes in any way…”

According to the signed Convention, migration was to begin on July 1, 1939. By then, all necessary formalities needed to be completed, such as the signing and ratification of the Convention, the preparation of lists of the population expected to migrate in the first year, securing funds, etc. The death of the head of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (November 10, 1938), on one hand, and the fall of the Stojadinović Government (March 1939), on the other hand, were the main causes for the delay in signing the Convention. This issue was raised in the second half of April 1939.

The Yugoslav Foreign Minister, Cincar Marković, on April 20, 1939, telegraphed the Yugoslav envoy in Ankara, Axhemović, about his meeting in London with his Turkish counterpart, Rushdi Aras, who reportedly declared that: “Turkey, after the recent events in Albania,” would not change its previous views and would accept to sign and finalize the Convention. One day later, Axhemović, agreeing fully with C. Marković, requested that the Convention be signed and ratified as soon as possible. Consequently, on April 25, 1939, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Yugoslav Kingdom, through an encoded letter, authorized Axhemović to discuss with Turkish government authorities the date of the signing of that document, as well as its ratification by both parliaments.

On May 4, 1939, he telegraphed C. Marković that the head of the Balkan sector at the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs had communicated the following: “…The Turkish government is ready to sign the Convention, but in the current situation, it is obliged to suspend any activities that are not in compliance with national defense. For the above reasons, since it cannot implement the convention, it must necessarily postpone the signing. Discussions can only occur if Yugoslavia is willing to increase its contribution to financing the migration…”!

In fact, the latest request from the Turkish authorities is best clarified in the Memorandum they submitted to the Yugoslav Legation in Ankara in July 1939, in which they proposed that the “total migration period” be divided into two parts instead of six, as stipulated in the Convention, and that: “the total costs necessary for the first part be fully covered by the Yugoslav government,” while, on its part, the Turkish government would “commit to fully ensuring the costs related to the transport and settlement of the other half of the migrants…”

Such a request was rejected by Belgrade, thus ultimately failing the ominous long-standing plans of the Serbian nationalists, which envisioned the expulsion, respectively the violent migration of the Albanian population from Kosovo and other Albanian territories outside political Albania to the Republic of Turkey, and their colonization with Slavic, specifically Serbian-Montenegrin elements.

Naturally, the political and diplomatic leadership of the Albanian Kingdom played an important role in the non-ratification of this document, which, as noted above, significantly increased its political and diplomatic activity as soon as it was informed of the agreement reached in Istanbul. At the World Council Congress for International Aid to the Church, which was held in August 1938 in Lavrik, Norway, the Archbishop of the Albanian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, Visarion, on the orders of King Zog, submitted a memorandum to the Minority Commission, in which the concern of the Albanian government was highlighted regarding the implementation of the “Agreement for the migration of Turks from Yugoslavia” not to also include the expulsion of Albanians.

Furthermore, the memorandum requested that all necessary measures be taken to prevent the migration of Albanians, while the implementation of the Convention “should be entrusted to a neutral commission.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Yugoslavia, on November 9, 1938, wrote to its Legation in Ankara about the significant reaction in Kosovo in connection with the appointment of Xhuxhul as the plenipotentiary minister and extraordinary envoy of Albania in Ankara: “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it is stated in the letter, has been informed that the appointment of the former Albanian consul in Skopje, Mr. Xhuxhuli, as a plenipotentiary delegate in Ankara, has caused a significant positive response among the Albanian population in Southern Serbia (Kosovo and present-day North Macedonia – Q.L.) and hope that, with his mediation, the migration of the Muslim population from our territory will be removed from the agenda.

The Albanian population considers that Xhuxhuli has been appointed as a delegate with the aim of clarifying and demonstrating to the Turkish government that the Muslim population, not only in the border areas with Albania but also in other parts of Southern Serbia, is of Albanian ethnic origin and not Turkish. Therefore, accepting that element, which is neither related to the Turks by blood nor by language, would present a burden for Turkey, which would only impede repatriation and the organization currently taking place in Turkey.

The Command of the Gendarmerie of the Vardar District Division in Skopje reported to the Ministry of Interior in Belgrade about a meeting of the Albanian elite held on March 20, 1939, in Tirana, in which it was stated that “Yugoslavia would not be able to carry out the migration of Albanians according to the Convention approved between Yugoslavia and Turkey,” considering the fall of the government of Millan Stojadinović, and that even to this day, neither the Yugoslav nor the Turkish Parliament had examined that Convention and it had not been implemented at all.

“The Albanian envoy in Ankara,” it further states in the report, “on the orders of the Albanian government, has taken the necessary step with the main Turkish factor to obstruct the implementation of that convention, the main architects of which are Qemal Atatürk and Stojadinović. The Albanian government has sent the necessary instructions to the Albanian consul in Skopje to inform the Muslim Albanian population in Kosovo that the plan regarding the migration of the Albanian people has failed!”

Generally speaking, if we refer to the contemporary Albanian diplomatic sources, then the number of Albanians who were displaced from Kosovo, the Eastern regions (present-day North Macedonia), the Preševo Valley (Eastern Kosovo), the Albanian territories in Montenegro, and Çameria to the Republic of Turkey, from the Balkan wars until the disintegration of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, reached about 350,000 individuals./ Memorie.al