By Qerim LITA

Part one

– The relocation of Albanians in the years 1912-1939 and the reaction of the Albanian state –

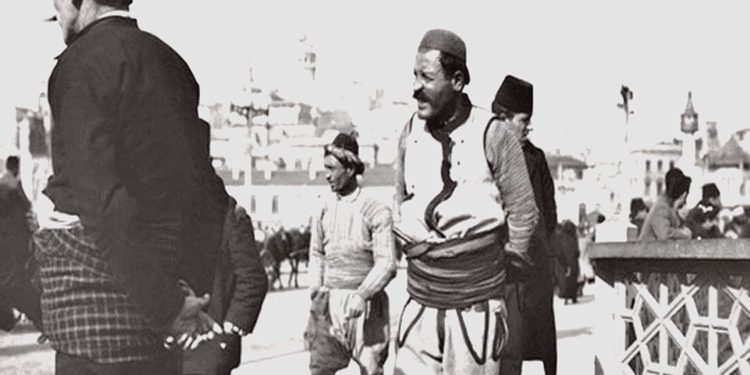

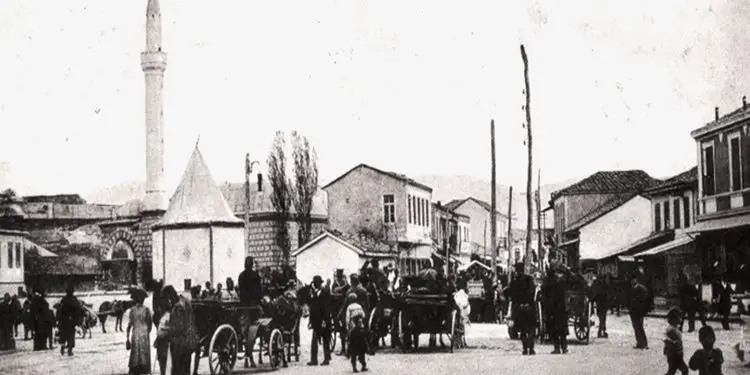

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the withdrawal of the Ottoman Empire, and the occupation of Albanian lands by the Balkan Orthodox alliance, the process of displacement of the Albanian population from their ethnic lands to the Republic of Turkey resumed. Recently uncovered documents shed light on the fact that within the year 1912-‘13, the Serbian-Montenegrin and Greek occupying armies violently expelled over 200,000 Albanians, the vast majority of whom settled in Istanbul, Anatolia, and other regions of Turkey. Meanwhile, according to an estimate by the Albanian Legation in Ankara, in 1928 there were 27,000 to 30,000 Albanian families in Turkey, displaced from Kosovo, the Eastern territories, and Çameri, including those Albanians who had emigrated after 1913.

All that violent policy implemented at that time by the Serbian-Montenegrin occupiers had one sole purpose: “To change the ethnic character in the regions where Albanians live at any cost.” As an example, we mention the horrific event that occurred in the spring of 1913 in Kërçovë, when Serbian Chetniks surrounded the entire city, entered Albanian homes, rounded up all the males, and took them to execute in specific places.

Some were executed in a place called “Çiflik,” another group in “Biçincë-Jurie,” and others in the primary school in the center of the city. After gathering all the male Albanians of the city in these three locations, the two well-known Chetnik criminals of that area, Vojvoda Mikail Brodi and Vojvoda Stanka Dimitrieviq, decided who among them should be killed by stabbing, who by shooting, and who by clubbing. Besides being killed in the most barbaric manner, all their belongings were looted.

It is important to highlight the fact that the majority of those displaced during the years 1912 – ’13 lived in miserable conditions because all their movable and immovable property was confiscated by the Slavo-Orthodox occupiers. Although they had once been citizens and subjects of the Ottoman Empire, with the establishment of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923, the overwhelming majority were denied Turkish citizenship, which further complicated their living conditions.

Under these circumstances, many of them wished to return to their birthplace, where they had left their homes and properties; however, this was not permitted by the occupying authorities of Belgrade, which recommended to their accredited representatives at the Consulate in Istanbul that when granting entry visas, care should be taken that: “among them there may be those who wish to enter our territory to remain with us.”

In addition, they launched a wide-ranging military-police campaign, ostensibly to capture the escapees, particularly members of the ‘Kaçak Movement,’ who were considered the military wing of the Committee for the National Defense of Kosovo (KMKK). The Turkish newspaper “TNIN” reported that the authorities of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (hereinafter referred to as KSCS) were implementing an unprecedented terror “against the local Muslim population.” As a result of this terror, many Albanian families were forced to abandon their homes to settle in safer places, the majority of them in Turkey, while a small portion stayed within the Albanian state.

Meanwhile, the Legation of Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian in Sofia, on June 3, informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Belgrade via radiogram about a new influx of the Muslim Albanian population from Kosovo and present-day North Macedonia to Turkey: “…Recently, Muslims from our territory are emigrating to Turkey. A certain number of such individuals are remaining on Bulgarian territory because the Turkish authorities at the border are preventing them from entering. Those displaced from Southern Serbia (thought to be from Kosovo and Macedonia – Q.L.) are now requesting through our Legation in Sofia to be allowed to return to our country…”

This legation viewed it as “unfair” on the part of the Turkish authorities to prevent the population from entering Turkey, as it was emphasized in the radiogram: “they are the displaced individuals who, before leaving the country, ‘have definitively declared themselves as citizens of Turkey,’ and that by this, ‘they have the right,’ as long as this issue does not receive a final resolution. During this period, the Greek government exploited the Treaty of Lausanne of January 30, 1923, to carry out an ethnic cleansing of Çameri, according to which there would be an exchange of Turkish and Greek populations between these two states.

During June 1923, the Greek authorities expelled all residents of 31 Albanian villages in Kostur and Follorin, amounting to 33,000 individuals. Meanwhile, in the autumn of that year, they increased pressure on Çameria. The Albanians of this region were ordered to vacate 75% of their homes, which would be occupied by Greek refugees, and the sale of their properties was blocked. Meanwhile, on November 7, 1923, the envoy of the Kingdom of Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian from Istanbul reported to Belgrade about his meeting with the Senior Advisor of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mehmed Beu, who conveyed to him the dissatisfaction and great concern of the Turkish government regarding the “real exodus of the Muslim population” from Kosovo to Turkey.

According to Mehmed Beu, such a phenomenon was extremely distressing for the Ankara government, which was already “in extraordinary circumstances with the displaced Muslim population,” which, according to the Lausanne Agreement signed on January 30, 1923, between Turkey and Greece, had begun to relocate to Turkey. This dire situation seemed to be the main reason that compelled the Albanian government to initiate the repatriation of the displaced Albanian population from Turkey to the Albanian state. For this reason, an Albanian delegation led by Eshref Frashëri, Chairman of the Assembly, Xhafer Vila, the first secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Nezir Bej Leskoviku, arrived in Istanbul on October 15, 1923. They were received by the Turkish delegation led by deputy Shukri Kaja.

During negotiations that lasted more than a month, the requests of both parties were examined and debated in detail. Among the most important demands of the Albanian delegation were: the recognition of Albania as an independent state; the resolution of citizenship issues, especially the recognition of Albanians in Turkey as citizens of Albania; customs and trade conventions; postal-telegraphic convention; that many Albanians who had served in Turkey as officials, either in the army or in administration, should have the right to pension, as these officials had left funds for pensions in the treasury… etc.

After the negotiating parties reached an agreement on all issues, on November 18, 1923, they signed the Treaty of Friendship between the Republic of Turkey and the Republic of Albania. In its preamble, it was stated explicitly: “The Republic of Turkey on one side, and the Albanian State on the other, considering the established relations between the two peoples during the five-century political unity of Turkish-Albanian and proclaiming their sincere mutual conviction that this relationship from the moment of establishing relations between the two countries will serve the fate and well-being of both peoples, have decided to sign the Treaty of Friendship…”

The issue of the repatriation of Albanians displaced in Turkey was included in Chapter III, Article 3 of the Agreement, which stated: “Those of Albanian nationality who are deported to Turkey and have reached the age of 18 on the date of implementation of this agreement and within one year may acquire Albanian citizenship. All those who obtain Albanian citizenship in this manner are obliged to leave the territory of Turkey within one year from the date of signing this agreement, under the condition that they may not return, while selling their movable and immovable property and settling all state and private debts and severing all ties. Until leaving the Turkish border, they will be considered citizens of Turkey.”

The establishment of diplomatic relations between Albania and Turkey was certainly not in favor of the then hegemonic policy of Yugoslavia, which engaged its diplomacy in Istanbul and Ankara to do everything possible to prevent the agreement from being reached. In this regard, the Consulate in Istanbul was the most active, reporting daily to Belgrade on the progress of the talks. On November 19, it reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Belgrade about the alleged failure of the negotiations. However, such news turned out to be inaccurate, as the Treaty of Friendship between Turkey and Albania, as mentioned above, was signed on November 18, while its ratification was left to occur after the upcoming parliamentary elections, which were to be held that same year in Albania. The events that took place in Albania during 1924, which are well known to the public, were the cause of the delay in the ratification of the Agreement. It was signed on July 16, 1925, after Ahmet Zogu returned to power.

A few months after the signing of the Treaty of Friendship, the Government of the Republic of Turkey opened its Legation in Tirana. The Government of the Republic of Albania also acted similarly, appointing the distinguished Albanian diplomat Rauf Fico as the plenipotentiary minister and extraordinary envoy in Ankara, and Asafa Xhuxhuli as the first secretary of the Albanian Legation in Istanbul in January 1926. We do not possess detailed data on the number of Albanians who agreed to be repatriated to Albania, but Yugoslav diplomatic documents clearly emphasize Ahmet Zogu’s and the Royal Albanian Government’s tireless efforts for their repatriation.

This effort did not cease within the designated timeframe set by the agreement, but continued throughout the 1930s. In September 1934, the Yugoslav Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a report from the Albanian consul general in Istanbul, F. Dervishi, detailing the activity of that consulate regarding the repatriation of Albanians from Turkey and the significant resonance that existed among the displaced at that time. Such an action was undertaken by the director of Agrarian Reform of the Albanian Kingdom, Hoxha Sali Vuçitërna:

“By order of that Ministry and the verbal agreement with the Director of Agrarian Reform, Mr. Sali Vuçitërna, upon his arrival in Istanbul, this representation did not hesitate to develop its activity among the emigrants from Kosovo who are in Turkey to return to Albania. The activity met with complete success, so much so that many Kosovar families currently in Turkey are ready to depart for Albania. Based on the promises of this Consulate, many of them have left their designated places as determined by the Turkish authorities and are now in Istanbul, prepared to leave for Albania. Their travel expenses, along with the costs of passports, amount to 4,000 gold francs…!”

At the time when the Albanian government was making maximum efforts for the repatriation of as many forcibly displaced Albanians as possible by the Yugoslavs, the Greek authorities undertook a violent action in Çameri, installing a large number of migrants from Turkey in the homes of the Albanian people of Çameri. As a result, many Albanian families from the villages of the municipalities of Filat and Gumenicë had registered their desire to relocate to Turkey.

On February 23, 1927, a letter arrived for the Chairman of the Republic, Ahmet Zogu, from Çameri, in which it was stated that the Çams, due to numerous sufferings “without schools, without any human rights, abused by Greek officials, wish to leave, as they are suffering so much and no one cares about their plight. The letter continues that it is clear the Greek Government intends to expel them from Çameri. The prefect of Janina seems to have sent Hasan Hamitin to tell them that if they sign a document that the Greek Government does not force them but that they wish to leave voluntarily, there will be no obstacles. As for the Turkish Government, it will accept them, provided they have some money with them…”

Further in the letter, it was stated that the Greek government would send one of its officials to register the houses and properties of the Albanians of Çameri, where part would be bought by the Small Asia Bank, while the rest by the National Bank of Greece. At the end of the letter, it was mentioned that “this blood minority will leave their homeland” due to the violence being used by the Greek government authorities, and that part of them; “if Albania accepted them, would go there to become Albanian citizens.”

The situation in Çameri worsened even more during the months of April-May 1927, as the Greek government, as it had warned, installed a large number of Greek migrants from Anatolia in the homes and properties of the Albanians. In such a situation, the Chamber of Deputies, in a meeting held on May 15, 1927, at the proposal of the deputies: Maliq Bushati, R. Kiçi, and Kol Mjeda, decided to summon the Government of Albania to explain the injustices being done to the Albanians of Çameri by the Greek Government. The text of the proposal stated that; despite the promises and commitments made by the Greek government to the League of Nations, it was implementing a violent and inhumane policy against the Albanian element in Çameri.

“According to the principle of minorities, – the text continues, – instead of enjoying all rights as Greek nationals, they are being denied their most natural and fundamental right to live. With the plundering of the homes of these wretched individuals, immigrants from Anatolia have been installed, who, by order of the Government, enjoy all their possessions such as gardens, olive groves, pastures, and fields, leaving the unfortunate Çams to die on the road…!”

Meanwhile, Xhafer Çela, Zenel Ypi, and Shahin Ypi wrote a letter to the Chairman of the Republic, Ahmet Zogu, in which they expressed their deep concern because a considerable number of Çams “are selling their property” in order to emigrate to Turkey. In broad terms, the Greek government, in the name of the exchange of populations with the Republic of Turkey, forcibly expelled all Albanian residents from 83 villages in Çameri. Regarding the expulsion of the Albanian population from Çameri, an analysis prepared in 1932 by the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army also mentions, among other things:

“…In the region of Çameri, from Northern Epirus, the largest number of local Albanian population has emigrated and has settled in Turkey and Albania. Their substantial wealth has remained in the territory of Greece. The Greeks have appropriated this wealth and distributed it to the migrants from Asia Minor…”

On the other hand, the Yugoslav authorities, inspired by the Law on Colonization, which the Turkish Parliament enacted on July 14, 1934, and which, among other things, foresaw the relocation of all Turks from the Balkans to Turkey, saw this as a key moment for the complete relocation of the Albanian and Turkish population from their homes to Turkey, with Slavic colonists being settled in their lands.

For this purpose, the Yugoslav Parliament, in a meeting held on August 21, 1934, made amendments and additions to Article 55 of the Yugoslav Citizenship Law, which was approved in 1928, with the content as follows: “Non-Slavs who, in the sense of the second paragraph of Article 55, have become citizens of the Kingdom, shall cease to be so if, after the entry into force of this Law and until November 1, 1938, they declare before the competent authorities of the first-level government, or any of our diplomatic or consular representatives in the outside world, that they withdraw from citizenship. Declarations submitted to the aforementioned authorities, as well as to diplomatic and consular representations by these persons, after November 1, 1938, and until entry into force of this Law, shall be considered as timely submitted…”

With this law, all Yugoslav citizens who did not belong to the Slavic ethnic group were “enabled” to acquire the citizenship of another state, and each of them who obtained a foreign passport and did not leave within a year would be forced by the Yugoslav authorities to leave Yugoslavia. In this way, a large number of Albanians, whose applications were not accepted by the Albanian State, were forced to relocate to Turkey, which, despite declaring that it would not accept Albanian migrants from Yugoslavia, nonetheless offered all facilities for them to settle in Turkey.

Consequently, at the beginning of 1935, news began to circulate about the Yugoslav-Turkish agreement for the relocation of Muslims, specifically ethnic Albanians. The Minister of the Interior of Turkey declared that the Republic of Turkey would bring 800,000 immigrants from Yugoslavia. The relocation of the Albanian population from Yugoslavia to Turkey, according to the prominent Albanian diplomat Rauf Fico, would continue, as it represented the “common interest” of both Turkey and Yugoslavia. Therefore, he suggested to the Royal Albanian Government to take all “necessary measures for the resettlement in Albania” of those Albanians who insisted on leaving Kosovo or other Albanian ethnic territories under Yugoslavia.

Meanwhile, the Yugoslav consul general in Istanbul, in an analysis prepared in May 1935, estimated that the Yugoslav Government should not promote the relocation of the Albanian population to Albania, because by doing so, the population of that state would increase and strengthen the “irredentist movement,” which was already being encouraged by the Albanian state itself. Instead, he proposed that the Albanians should relocate to Turkey, because according to him; “that Albanian element” which relocates to Turkey is considered “an element lost forever.”

During this time, the Land Reform Office in Skopje began a wide-ranging campaign of confiscation of fertile land in Albanian settlements. The action stipulated that “Albanian peasants would be allowed only 0.4 hectares of land per family member.” The goal of this anti-Albanian policy, as reported by numerous police and military sources from Yugoslavia, was to “despair the Albanian inhabitants,” especially those in villages stretching along the Shar Mountains to the Kumanovo-Prishtina area, where the Albanian compactness was quite high. The authorities in Belgrade hoped that through these harsh agrarian measures, they would force the Albanians to abandon their homes and relocate to Turkey.

The envoy of the Albanian Kingdom in Belgrade, Rauf Fico, wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stating that “by implementing various colonization laws and agrarian reforms, hundreds of Albanian families have had their lands and homes seized,” and this was the true cause of the emigration of Albanians to the Republic of Turkey. In the supplementary report dated May 18, 1934, R. Fico informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the Yugoslav authorities on March 25, 1934, had ordered the inhabitants of the villages in the Gjakova district: Batush, Nivokaz, Moglicë, Brovinë, Palabardh, Stubëll, Berjah, Ponoshec, Popoc, Shishman, and Babaj Boka that “they could no longer work their lands, which fell under the agrarian reform…” /Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue.