From Sokrat Shyti

Part Twenty-One

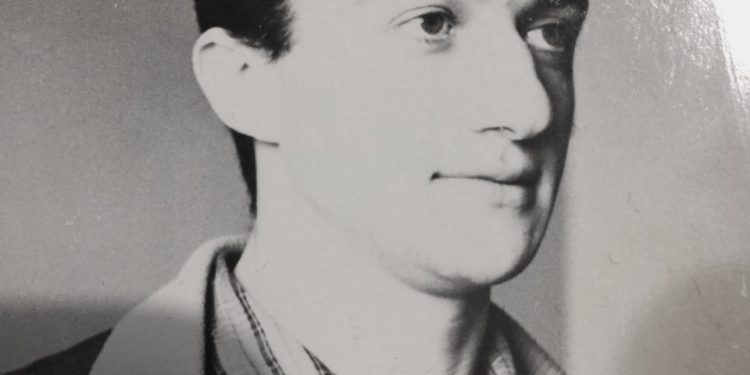

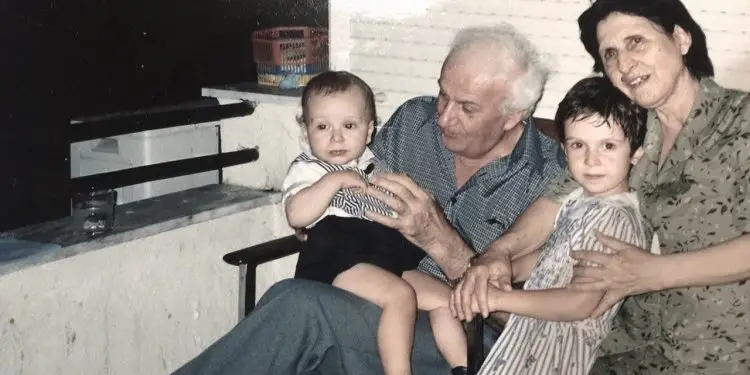

Memorie.al / The writer Sokrat Shyti is the “great unknown” who, in recent years, has revealed the tip of the iceberg of his literary creations. I say this based on the limited number of his published books in recent years, primarily the voluminous novel “Nata fantazmë” (“The Phantom Night”) (Tirana 2014). The novels: “Përtej Misterit” (“Beyond Mystery”), “Mes Tundimit dhe Vorbullës” (“Between Temptation and the Whirlpool”), “Gërmimet e Makthit” (“The Excavations of Torment”), “Hija e Turpit dhe e Vdekjes” (“The Shadow of Shame and Death”), “Koloneli Kryedhjaku” (“The Chief Colonel”), “Shpresat e Nëmura” (“The Damned Hopes”), “Pështjellimet e Fatit” I, II, “Mbijetesa në Kasollen e Lopës” (“Survival in the Cow Shed”), as well as other works, all novels ranging from 350 to 550 pages, remain in manuscript form awaiting publication. The dreams and initial enthusiasm of the young novelist returning from studies abroad, filled with energy and love for art and literature, were cut short early by the savage blade of the communist dictatorship.

Who is Sokrat Shyti?

Returning from studies at the State University of Moscow, shortly after the severance of Albanian-Soviet relations in 1960, Sokrat Shyti worked at Radio “Diapazon” (which at that time was located on Kavajës Street), in an editorial office with his journalist friends – Vangjel Lezho and Fadil Kokomani – both of whom were later arrested and subsequently executed by the communist regime. Besides the radio, 21-year-old Sokrat, if we can picture him then, had a passionate literary interest. He wrote his first novel “Madam Doktoresha” (“Madam Doctor”), which was on the verge of publication, but alas! Shortly after the arrest of his friends, to top it off, one of his painter brothers escaped abroad.

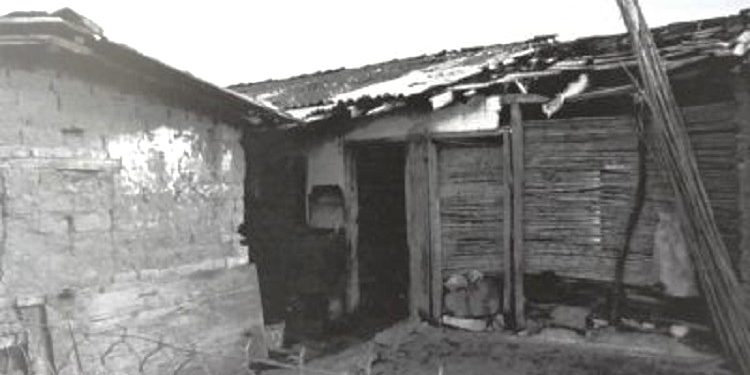

Sokrat was arrested in September 1963, and in November of that year, he was interned along with his mother and younger sister in a place between Ardenica and Kolonje of Lushnje. For 27 consecutive years, the family lived in a cowshed made of reeds, without windows, while Sokrat was subjected to forced labor. Throughout those 27 years, he was legally required to present himself three times a day to the area plenipotentiary. He had no right to move from the place of internment and was deprived of any documentation, etc. Under these conditions, amidst this cowshed, he gave birth and raised children. It was precisely from this event, or more accurately, a very long story of persecution, that he based his writing of the book “Mbijetesa në kasollen e lopës” (“Survival in the Cow Shed”)!

Agron Tufa

To be continued from the previous issue

EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK, “SURVIVAL IN THE COW SHED”

– “So many calamities have happened to your mother by this age that I wonder how I am still alive, breathing, and haven’t gone insane!… I only have your trouble. Why, my son, did you return from Moscow? If you had stayed there, when we broke off with the Soviets, perhaps this misfortunate figure of ours, who has been a plague, wouldn’t have gotten it in his head to cause us harm, and we would have stayed living in Tirana. At most, they might have moved that misfortunate figure from his job, but they wouldn’t have exiled us to the cowshed!”…

– “Well, it was written that our fates would take a downward path!” I replied, not daring to make a remark, to tell him that next time this meaningless complaint should not be repeated, since it only saddens us! After two days, the chairman of the locality, in the presence of the Plenipotentiary, informed me that the director of SMT had given consent to employ me as a fuel supplier, in other words, a porter (despite the embellished title: supply secretary). So, I was supposed to distribute oil in cans to all the tractor drivers working in the joint agricultural cooperative area.

– “Let me tell you from the start: the job is quite exhausting. Because from morning until evening, you will walk kilometers through the furrows, carrying a can of oil, and during lunchtime, you will bring them food, since they can’t interrupt their work to go to the cooperative’s canteen. The job requires you to wear old clothes and rubber boots, especially when the weather is damp and the mud is hard to break through. You will certainly need a raincoat. I didn’t call you here to hear your opinion, but to order you to start working immediately! As a journalist, you must know the law of parasitism: those who do not go to work are forcibly summoned by the organs of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and will not be paid for a certain period of time!

Of course, harsher punishments will be applied to you, which I believe you take into consideration…! Now, you will report to SMT, accompanied by the Plenipotentiary, and there you will be given concrete instructions on how to carry out your duties. One more piece of advice: you will take your lunch with you, as you will only return home when it gets dark. If there is any family request for the authorities, you will first relay it to the Plenipotentiary, in one of the three cases when you present yourself.

From this moment, the path of physically painful suffering, alongside mental and spiritual torment, began. Gradually, the pain was extending toward the marrow, to test how long my endurance would last. It was a winter Sunday, with temperatures several degrees below zero and the frozen ground had the hardness of concrete. Thus, the tractors had moved away from the furrows and gone to repair points, where services are provided by mechanics in collaboration with the tractor drivers. This situation allowed me to stay in the hut with my family and warm myself by the tin stove.

It was so cold that the warmth of the flames roaring inside the stove seemed to be wasted in the ceiling less, floorless space because the frost seeped through the window panes without glass and from the so-called “door,” which the forest guard had made with reeds. Since the tractor drivers didn’t recognize days off, as agriculture, being an industry without a roof, depends entirely on the whims of the weather, I was obliged to work even on Sundays.

Three months had passed in this arduous existence, completely disconnected from the experiences of journalism in broadcasting. Yet, my mind often wandered to Vangjeli, my colleague from the youth editorial office, whom I anxiously asked how he was coping with loneliness in his cell. After this question, the same gnawing thought seized me—that I would have been better off if they had arrested me and put me in prison, without touching my family, my mother, and sister, because inside I wouldn’t feel as humiliated and despised as I did out here, knowing that I would be surrounded by other fellow sufferers with whom I could exchange a few words.

Of course, I didn’t dare to express this thought to my mother; I kept it deep in my consciousness. And here, I would always keep it, as a kind of hostage, so as not to add to the pain of experiences. While I was sitting by the stove with my outstretched hands, wrapped in such sad uncertainties, an unknown voice was heard from outside, calling my name. My thoughts automatically went to work: perhaps a courier from SMT was coming with orders from his brigade leader to tell me to report to a certain plot, where perhaps the frozen ground had started to thaw and the plow needed to be moved, thus I had to take a ten-liter can of oil to the tractor driver!

– “Are you really going out in this wild frost again?!” my mother lamented.

– “If they’re asking for me, I must go!” I replied, hugging her before I stood up to see. The voice repeated from the same distance: perhaps he was afraid to approach because of the dogs, although during the day, the forest guard kept them tied up. When I stepped out from behind the hut, the unknown person saw me and didn’t wait for me to ask who had sent him but quickly said in one breath:

– “Someone from Tirana is looking for you, with a car!”

– “Specifically, me, by name?!” I was momentarily taken aback.

– “By name and surname. There’s no other Sokrat Shyti here and in the entire Lushnja district. The car stopped at the Kolonja bend. He asked me about you, where you live. I was immediately ready to help: I got in the car. He is waiting below.”

– “What does he look like?” I asked. “An elderly man, tall, with short hair, and a serious expression.”

Although this external description completely matched the image of the General Secretary of the Writers’ Union, I still had some doubts. Perhaps it was my inner desire to meet someone with a great spirit (after these months of gnawing stress, filled with insults, humiliations, and threats) that led my imagination to believe in the truth of this assumption. Nevertheless, it seemed more like a beautiful image of a dream rather than a possible reality. I descended the hill through the narrow path, just as I was dressed, and went out to the street with my gaze fixated on the gray Soviet-made “Pobjeda” car.

At that moment, the first door opened, and my benefactor appeared before me, dressed in a thick black cloth coat that reached down to his ankles. But even though he stood a few steps in front of me, I couldn’t believe my eyes: perhaps the January frost created a mirage with his silhouette and portrait! His characteristic deep voice contradicted this illusion. Still, I held back; I didn’t run towards him because I still didn’t know what thoughts were running through his mind and couldn’t imagine why he wanted to meet me: perhaps he brought some proposal on how to escape from the abyss, or he was sent specifically on a special mission by the high-ups to negotiate with me, to bluntly tell me that the easing of my punishment could only happen on one condition: to write a novel using the method of socialist realism, according to the familiar scheme that dominates in Albanian artistic literature, with revolutionary pathos, where characters with high party loyalty act vividly, self-sacrificing for the sacred cause of socialism!…

He sensed my hesitation and approached me slowly, opening his arms to embrace me with paternal affection. Then he slipped his arm through mine as if we were going for a stroll, and we moved a few meters away from the car. It was a clever move, so the driver, who was acting as both escort and eavesdropper, wouldn’t hear us.

– “I was abroad, in a delegation, when the misfortune happened in your family,” he began to speak with a calm, slow tone. “But even if I had been here, despite my great desire and efforts to help you, I still wouldn’t have been able to succeed. At most, I could have met some member of the Government Committee for clarification, and of course, I would have said good words about you. Whoever that might be, they would only listen, without being influenced at all by this intervention. Because you must understand that the members of any government commission, especially this one for Internment-Exile, have an extremely rigid procedure: besides the one who reports, the others tend to be quite cautious and careful, and do not express personal opinions.

Very rare exceptions can only be made if the most influential member, the Minister of Internal Affairs, presents a special addendum to the committee, where he states, for example, that the punished person could perform a significant service if infiltrated into foreign espionage. As for the form of your punishment, why are you isolated from the others, why weren’t you sent to a common point, but brought here, I cannot provide any explanation! But in Tirana, how were you treated when they informed you about your brother’s escape?” he asked.

– “Horrifically! Terribly harsh and brutally,” I replied. And I briefly described the scene at Selvia with the tall colonel.

– “What about your mother at home? How did they treat her?” he added.

– “The same, with the same ferocity! They used a harsh, derogatory, mocking vocabulary! They turned upside down her only living space and took my manuscripts with them!”

– “Did they return them later, or did they keep them?” he asked with much interest.

– “They burned them cynically before my eyes in the corner of the courtyard of the Ministry of Internal Affairs! The sole reason for this action was my very fine, almost unreadable handwriting. From their complaints, it emerged that they were ‘tortured’ all night with magnifying glasses until they concluded that it was impossible to decipher it, so the only solution left was to propose to the big boss to destroy the manuscript…!”

– “You must have experienced an incredibly painful scene!” the writer sighed deeply. “The most atrocious torture for any creator. They have ripped a part of your soul and heart! However, this cruel act has a ‘salvatory’ side to it because it eliminates any chance of using the manuscript against you, quoting later a saying, phrase, or monologue of a character that could be manipulated by witchcraft penmen.”

– “But the greatest threatening evidence remains, the typewritten copy of the novel ‘Madam Doctor’, ” I seized the opportunity to inquire about the fate of the novel.

– “Fortunately, the novel is in my hands!” he hurried to say with a warm gaze. “And for safety, I will keep it because sudden raids could occur at your shelter. I don’t know the source of the rumor, but what matters to us is that in the editorials of the Writers’ Union, there is talk of the ‘losses of the manuscript of the novel. And since all civil rights have been stripped from you as the author, the anxiety of some has evaporated regarding whether the novel will be published as a book in its own right, or fragments in the magazine ‘Nëntori’? This means you will not have any further harassment or inquiries. The chapter closes here, without disturbing us about the future.

“Therefore, it is essential for you to have found within yourself the strength to face survival in these conditions!” he added with a sympathetic gaze.

“This meeting today with you serves as moral and spiritual support for me. I believe it will be fixed in my memory for the extraordinary value it carries, considering the fact that a high-ranking official of Albanian letters goes out of his way to publicly greet a young, declassed writer who will continuously remain in the quarantine of punishment, to remain unknown and anonymous!” I emphasized with a tone of gratitude, realizing that our meeting was coming to an end.

“I will do my utmost to see you and exchange ideas whenever I pass by here on duty, certainly if I travel alone, without other companions, and you are in your shelter!… But regardless of how circumstances intertwine, you must never lose faith that you are a ‘distinguished prose writer,’ despite your young age, as I emphasized in my personal declaration addressed to the Minister of Education. I have full confidence that the blessed day will come when you will shine with great works!”

After this heartfelt appreciation, which rang in my ears like the thunder of a rainbow of hope, we embraced each other amicably! For a long time, his words swirled in my head: “You are a distinguished prose writer, despite your young age… and that; ‘the blessed day will come, and you will shine with great works!’ But when will it come? How long will this wait last? For years or decades?!… The stop of the General Secretary of the Writers’ Union at the Ardenicë bend, specifically to meet the interned Sokrat Shyti, spread with the speed of sound throughout the entire Lushnja district and attracted the authorities’ attention.

Some felt offended by this so-called “liberal” behavior, so they wanted to take revenge on me, to show this idealistic militant that “such micro-bourgeois tricks won’t work here, nor can they soften the class struggle by supporting a declassed individual!” Two days later, on Tuesday evening, around 8:00 PM, the local operative appeared like a sphinx in the frame of a reed door that served as the entrance to the room, and with a curt order and a stern tone, addressed me:

“They’re asking for you at the Internal Affairs Department! Right now! So, get up and get dressed!”

I immediately understood that this call at night (which could last who knows how long in the cells of the Department) was made as an act of revenge against the “liberal,” venting the anger and hatred toward me.

The Deputy Chairman of the Department met me with his feet planted, shouting as loud as he could that I should forget once and for all who I was before internment, a journalist who roamed freely throughout Albania!

– “So, get your head straight and don’t make mistakes like the one you made the day before yesterday, when you went swaggering to meet the head of the Writers’ Union to tell us: Here I am. I have the same value as before!”

– “That was a coincidence…” I wanted to explain myself.

– “Shut your mouth, I don’t want to hear your voice!” he threatened.

– “It was a coincidence,” I repeated.

– “Enough with the nonsense, it doesn’t fly with me!” he shouted, furious. “Otherwise, I’ll throw the handcuffs on you and throw you into the cell! Let me say, as the official representative of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat: You are nothing, a zero with a tuft, a hopeless failure that we can crush like a flea under the nail of our big toe! Get this through your head: in the mud and mire of Myzeqe, your youth and old age will pass until you die!… If you dare a second time to meet any personality, know this: I will lock you up in the cell so that you sleep on cement like a dog and only have bread and water to eat!…

Did you understand? Now get out of my sight because I can’t stand to see you! And head toward the cowshed! And there, it’s unnecessary, as you could end up at the dog’s kennel!… What are you waiting for?! You don’t hope we’ll find a car, do you? Start walking! If you’re lucky and a truck comes by and the driver wants a companion at night, you might save yourself a three-hour walk…?!”

But despite his malicious and humiliating intent, the last words served as a guide, showing me how to act when I came out of the heavy iron door of the Internal Affairs Department. Therefore, I turned to the location of the traffic officer and asked him to find me any car going to the Ardenicë bend. Fortunately, after half an hour, a truck loaded with bricks that was heading to Fier stopped, and the driver was willing to take me.

– “It’s clear that you’re not a villager and a resident of these areas. If I’m not mistaken, you must be that journalist from Tirana, living in the cowshed of that scrawny forest guard. I believe you must be in trouble. We, the drivers, get this kind of news first. I know you are an honorable family, and that’s how you’ll remain for us simple folks, regardless of the nickname they give you. The shavings, my friend, no matter how finely you grind them, they remain shavings, they won’t turn into flour.”

“I have heard that a villager, wherever he goes and whatever clothes he wears, does not change his nature. At least three generations must live in the city for them to gradually adapt to urban behavior. In my opinion, to prevent the cities from becoming corrupt, villagers should not be placed in leadership positions within the Executive Committees and the Party.

Villagers have the mindset of bringing their entire kin and friends to the city, rather than thinking about how to improve the lives of the residents. However, recently, there has been a noticeable influx of villager leaders. They appoint educated villagers as heads of cooperatives or councils, which is sensible since they know the troubles and issues of the village well. But these individuals cannot manage city life because they have no idea about it. Therefore, they will inevitably spread their village customs and behaviors.

If I am allowed to ask, since the road has crossed our paths: now that the wheel has caught your tail, what job have they assigned you?” /Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue

Copyright©“Memorie.al”

All rights to this material are exclusively and irrevocably owned by “Memorie.al”, in accordance with Law No. 35/2016 “On Author’s Rights and Related Rights”. It is strictly prohibited to copy, publish, distribute, or transfer this material without the authorization of “Memorie.al”; otherwise, any violator will be held liable under Article 179 of Law 35/2016.