By Eugen SHEHU

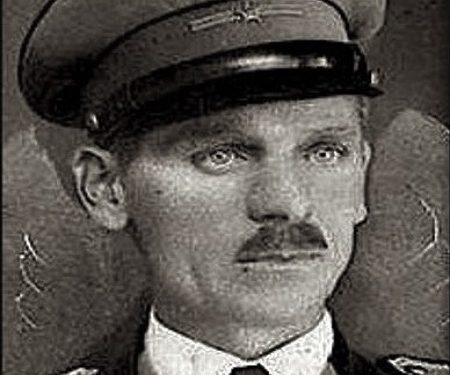

Memorie.al / Murat Basha was born in the village of Plan të Bardhë in Mat in the distant year of 1900. The Bashas of that time were prominent not only in Mat but throughout the Albanian territories. Veli Basha, Murat’s grandfather, during the glorious years of the Albanian League of Prizren, was the right hand of Xhelal Pasha Zogolli, Iljaz Pasha Dibra, and the entire brilliant array of military leaders, who, through their struggle, demonstrated to Europe that the ethnic borders of Albania were difficult to breach.

Moreover, through their heroic act of demanding autonomy, they conveyed to the Sublime Porte that they knew not only how to defend, but also how to govern. Veli Basha, at the head of the brave men of Mat, participated and fought particularly in the Albanian territories in Montenegro, where the danger was greatest.

In the 20th century, Murat’s father, Hyseni, became closely involved with the Albanian autonomist movement and maintained an unwavering friendship and commitment with the Zogolli family. In the Bashaj family home in Plan të Bardhë, secret gatherings were organized where discussions about the Monastir Committee would take place, what it had decided, and what paths were worth pursuing to spread the idea of the sweet independence of Albania among the people. Precisely in this environment, where men took up arms to take charge of the fate of the country, while the river of Mat flowed not only through its valleys and stones but also through legends, Murat Basha grew up and matured.

Said Najdeni often visited their home, and under the guise of a dervish, he would bring Albanian books and teach young Murat not only to write and read the beautiful Albanian language but also the glorious history of our nation. At the same time, in his youth, Murat Basha formed a deep friendship with the Zogolli family and, in particular, with the only son of this family, Ahmeti. However, this friendship flourished especially during the years 1917-1918, when new events would knock not only at the doors of the towers of Mat but across all of Albania.

As is known, the great Congress of Lushnja, held in January 1920, elected a new government, composed of a group of distinguished men committed to patriotism. Among other things, this assembly, by unanimous vote, appointed Ahmet Zogu as the Minister of the Interior of the Albanian state. At this time, Murat Basha, leading dozens of Mat warriors, along with other Albanian leaders, organized the protection of the Congress of Lushnja from both the Italian military forces and from some deceived Albanian brigades, who, in exchange for money, were ready to fight against the establishment of the state of Albania.

The act of the young man of Mat, the Minister of the Interior of that time, Ahmet Zogu, is now well-known, as he faced the Italians (especially in Durrës), where they set traps to prevent the government from going to Tirana.

Taking upon himself the sublime moment, the death for the homeland, Ahmet Zogu faced the insistence of the Italian military. Thus, the government’s path was paved, while beside Ahmet Zogu stood Murat Basha, the 20-year-old with a tall frame like a sapling, dressed in the traditional attire of Mat, armed with a mountain of love for his homeland. After taking on a significant role in the Albanian state of those years, Ahmet Zogu faced a series of major obstacles.

First was the Yugoslav intervention in the North of Albania, where thousands of regular soldiers from Belgrade, to implement the notorious Serbian plans against the Albanians, violently occupied vast areas of land within the political borders of the mother state.

In cooperation with the Minister of War, Ahmet Zogu responded to this intervention with frontal war, tooth for tooth, while the Albanian government undertook other political and diplomatic steps. The truth is that Ahmet Zogu, despite being in the role of Minister of Interior, did not gather and organize troops for his own protection but fought alongside the brave men of Mat alongside Murat Basha and his friends until the last Serbian soldier left the Albanian state border.

Murat Basha, together with other men from Mat, would continue to remain under the orders of his friend, Ahmet Zogu, even during the fights in Northern Albania against the Montenegrin forces. In January 1923, when the Albanian Prime Minister Ahmet Zogu was once again to face the Yugoslav forces, this time in Dibra and Starovë, he ordered Murat Basha and several other popular leaders to drive the Serbian soldiers out of the state borders.

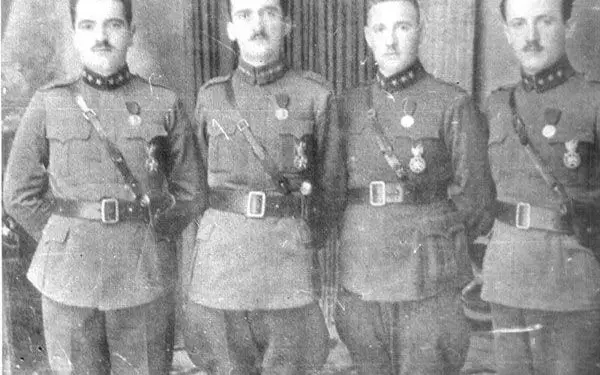

“After the restoration of Legality, on December 24, 1924, President Zog charged Hysen Selmani with the difficult task of directing reforms in the Armed Forces and the Albanian National Army, especially in creating and modernizing the special unit of the National Guard, later the Royal Guard. In this extremely important and delicate task, Colonel Hysen Selmani had Major Murat Basha by his side, and these distinguished military men successfully completed this mission. By personal order of the president, Major Murat Basha was appointed Commander of the Gendarmerie School” (Newspaper “Atdheu,” Tirana, June 29, 2003).

Not only in this high function but also in those he later took on, Murat Basha would do everything possible for the weapon of the Albanian Gendarmerie to be modernized and strengthened day by day. Not without reason, King Zog called in British specialists for this weapon, during which their experience turned into an invaluable school not only for Murat but for all other Albanian cadres, who intertwined the knowledge they gained with a patriotism nurtured since infancy. At the same time in these functions, Major Murat Basha would also showcase his patriotic personality. Especially during the years 1936-1938, when the Italian intervention in Albania became increasingly evident, Murat Basha became a powerful barrier against this intervention within the ranks of the gendarmerie.

He ensured that this very delicate weapon always served its people, without ever becoming a toy of political clans, no matter how important these might be. Throughout these years, Murat Basha was honored with orders and medals from the King of the Albanians, Ahmet Zogu. The April 7, 1939, just like in the lives of all Albanians, would bring changes for Murat as well. Now his name was quite well known to fascist Rome, leading him to leave Albania, as well as hundreds of other patriots, with the hope that they would again rush to those mountains and shores, in search of eternal freedom.

For about a year, Major Murat Basha would be kept isolated from the Serbs in one of the military garrisons in Gostivar. Later, he would connect with Colonel Hysen Selmani and Abaz Sul Kupin, with whom he began organizing to return to the homeland in order to fight together against the Italian occupier.

At the beginning of 1942, in complete illegality, Murat Basha started organizing the anti-Italian resistance in Mat and alongside Dule Allamani, Sul Kurti, and others, aligned himself with the forces of Abaz Kupi, during which they engaged in a series of fierce battles until the capitulation of fascist Italy on September 9, 1943. In the months that followed, especially after the Albanian communists turned their backs on the “Mukje Agreement,” Abaz Kupi and his followers fully realized that the clique in Tirana had its eyes on the communists in Belgrade. Therefore, they sought by every means and way to find other alternatives for the honest Albanian nationalism.

Hoping for a possible return of King Zog to the homeland as a unifying and mobilizing factor for all Albanians in the war against the occupier, these men formed the Party of Legaliteti in November 1943: At this assembly, Murat Basha, now tested not only for his military capabilities but especially for his patriotism, took on the role of leader of the legalist staff. From the first days of its establishment, this staff would face two enemies. On one side were the German occupying forces, and on the other side, the Albanian national liberation groups, who fired a couple of shots for show against the occupier and fought, shedding torrents of blood with their brothers who thought differently.

Without wanting to bring many arguments about this idea, I find it appropriate to include in these lines an authentic document from the very historiography of the communist Tirana, regarding the situation at that moment, which states textually: “The Fourth Brigade and the Fifth Brigade had the mission of destroying Abaz Kupi’s forces. On July 3, the General Commander of the UNÇSH emphasized once again to the Staff of the First Division: We have warned you that you must not let the Base gather forces and form a front against us. Do not neglect this warning, as the responsibility falls on the Division Staff.” (“Documents of the General Staff of the UNÇSH” – Tirana 1976, page 466).

Thus, it was clearly seen that the partisan groups, as their main objective, had the attack on nationalist forces according to orders received from Belgrade. Meanwhile, the nationalist forces operated quite differently.

Major Murat Basha, intuitive, often sensed the danger from the partisan groups and did everything he could to avoid the fratricidal war. In close cooperation with the brave man from Kruja, Abaz Kupi, they did everything to avoid fighting brother against brother; rather, they sought to meet, to talk, to assuage grievances by giving their word, just as Albanians had traditionally acted when the gun of the enemy echoed at the doorstep. In his book “The Sons of Albania,” the British author Julian Amery (a senior officer of the SOE, near the staff of Abaz Kupi), presents with facts and concrete events that in many instances, the Zogist leaders avoided fratricidal war, although in some cases against their will.

Especially in the mountains of Kruja, Martanesh, and Shpal, where the nationalist forces were made up of innocent 15-16-year-old boys from the southern part of the mother state, the legalists never accepted conflict. They opened paths for these young, rising boys, while the communist clique in Tirana spread and rejoiced over pamphlets, claiming the escape of the legalists from sight, or their complete dismantling.

In fact, he does not forget to mention that in the summer of 1944, around Abaz Kupi, about 10,000 men could gather. In this regard, I believe that the contribution of his chief of staff, Major Murat Basha, was not small either.

With the fall of the government led by Rexhep Mitrovica, the communist clique in Tirana began to commit crimes in broad daylight, killing Albanian men and boys who were connected to the Nationalist Movement. Furthermore, they continued to organize their brigades, and in this way, the red terror spread throughout Albania.

At that time, Murat Basha was staying with his combat staff in the region between Laçi (Kurbini) and Burrel, but he intuitively felt that the fratricidal war was taking on unprecedented dimensions. In a meeting in the early days of August 1944, he expressed this concern, as the commander of the Zoguist staff, to the British representatives Maclin and Emery.

Especially when, under the orders of Enver Hoxha and Tito, the partisan brigades began their incursion into the North, many nationalists did not want this military action, foresee the rivers of blood that would be shed. This new wound for the Albanians would, of course, be opened by the communists of Tirana and Belgrade. They acted against the will of their own people, and even the 50-year communist historiography states textually: “After the passage of the First Division to the North, many traitorous leaders, such as Abaz Kupi, Murat Basha, Ramadan Kaloshi, Seit Kryeziu, and others, called on the English mission for the Allied Command in the Mediterranean to exert its influence to stop the march of the partisan forces towards central and northern Albania.” (“History of the National Anti-Fascist Liberation War of the Albanian People” – Tirana 1989, volume 4, page 403).

Thus, it was clearly seen that the partisan forces, as their main target, had the destruction of nationalist forces according to orders received from Belgrade. Meanwhile, the nationalist forces acted quite differently.

Major Murat Basha, intuitive, often sensed the danger from the partisan brigades and did everything he could to avoid fratricidal warfare. In close cooperation with the brave man from Kruja, Abaz Kupi, they did everything to avoid fighting brother against brother; instead, they sought to meet, to discuss, to alleviate grievances, giving their word to one another, just as Albanians traditionally acted when the enemy’s gun thundered at the doorstep. In his book “The Sons of Albania,” British author Julian Amery (a senior officer of the SOE, near the staff of Abaz Kupi), presents facts and concrete events that in many instances, the Zogist leaders avoided fratricidal war, although in some cases against their will.

Especially in the mountains of Kruja, Martanesh, and Shpal, where the nationalist brigades consisted of innocent 15-16-year-old boys from the southern part of the mother country, the legalists never accepted conflict. They opened paths for these young boys, while the communist clique of Tirana spread and rejoiced over pamphlets, claiming the escape of legalists from sight or their complete dismantling.

Thus, in the final days of October 1944, when it became apparent that the Kalaja e Prezës was being surrounded by thousands of communist partisan forces, it was again Murat Basha, along with other nationalist commanders, who left the country without firing a single shot, solely to avoid shedding the innocent blood of Albanian boys. Furthermore, in November of that year, he quietly dispersed his staff, and in his final meeting with Abaz Kupi, he communicated to him that in any case, at any moment the Monarchy required it, Murat Basha would be not only a military figure but also an unwavering royal supporter until the end of his life.

With the usurpation of Albania by the terrorist communist clique of Albanian-Slavic origin on November 29, 1944, a great vengeance of the national liberation brigades began against anyone who had expressed ideas and views contrary to communism. In this wave of terror, Major Murat Basha, that silent but brave man, was also taken and locked up in the notorious prison of the capital.

There, after the deliberate farce of the supposed “unmasking” of traitors, the executioners, led by Koçi Xoxe and Bedri Spahi, sentenced Major Murat Basha to death by shooting. He calmly accepted the sentence and one night before his execution, he asked his friends for a pen and paper and wrote these lines to his wife:

“Ah wife, oh my unfortunate wife! For seven years now, your heart has known only sorrow, tears, and grief, meaning since April 7, 1939, and you, oh blessed one, endured with all the children, struggled, burned, and were scorched. So too did you fall and wage your war. And why? To gain freedom! Yet today, as we anticipated with joy the right, the effort, sweat, and blood shed instead may have been destined to become a victim of our sufferings. Oh what sorrow! My dear, do not despair, but I beg you once again, be strong and endure, for I am becoming a sacrifice for the holy Freedom.

The whole world knows my cause and appreciates it well. I give you this message; please take great care for the fate and education of the children, and give them some trade. The house is yours; I believe they will not take it from you. Do as you can, and may God help you. I trust that friends will not let you down. I wish that the grave will not be lost. The clothes I had with me in prison, you will find listed attached.

Keep them as dear reminders from our side. Meet with Meti, as he may help you. Please pass these letters to the addressees. I do not regret dying, for I die for Freedom and for our great cause. But I have great concern for your fate and that of the family circle because I know in what condition I leave you, and I cannot describe my despair, but may Almighty God help you. Therefore, once again, I beg you and tell you to be very patient. I close by kissing and embracing you always in your heart, Murati. And one last request; do not shed tears; only be patient!” (Newspaper “Atdheu” – Tirana, June 29, 2003).

The next day, 12 nationalist men, shackled with the heavy chains of prison, were brought before the firing squad. Among them was also a young boy, who stood firmly on his feet. With a loud voice to encourage him, Major Murat Basha said, “Hold on; you are a man!” Then all the death-row inmates sang the national anthem. The other prisoners in the cells began to sing the great anthem of the Albanians as well. Then the gunshots of the criminals echoed; among the shots, the powerful voice of Major Murat Basha was heard, “Long live Ethnic Albania! Long live the King!” Thus ended the physical life of the valiant monarch. /Memorie.al

Bern-Zurich