By Prof. Assoc. Dr. Sonila Boçi

The first part

Memorie.al / The year 1946 marked a turning point in the history of Albania, but also beyond. The contradictions between the Great Allies, the USA, Great Britain, on the one hand, and the Soviet Union, on the other, were becoming more and more apparent. The ideological war, the extension of the areas of influence and the imposition of governance systems, had caused what Wilson Churchill would consider the “Iron Curtain” to fall in Europe. This situation would directly affect even a small country, like Albania.

As for internal politics in Albania, the victory in the elections for the Constitutional Assembly gave a kind of peace to the Albanian communist leadership. With these elections, it had fulfilled its first objective, the legitimization of power. The elections had been the main condition of the Western Allies, to recognize the new Albanian government and to establish diplomatic relations with it.

The proclamation of the People’s Republic, on January 11, 1946 and the approval of its Statute, on March 14 of the same year, legally sanctioned the program of the Front, but the popular mandate of the “people’s power” remained controversial due to the legal package, with which elections were organized; cases of manipulation of their results and, above all, because of the 20 deputies who were dismissed, imprisoned or executed during that legislature. Despite this, the elections had opened the way to fulfill the second and even more important objective, “the establishment of a new order and its maintenance”.

At the beginning of 1946, the senior leaders of the Communist Party of Albania and the Albanian government were more determined to take some measures in the political and economic field, to strengthen the communist regime in the country. In the political aspect, the Albanian communists were tough and decisive in the creation of the political-administrative, judicial and military bodies of the Albanian state, controlled by the NPSH, which continued to remain semi-illegal within the Democratic Front.

In the economic field, steps were taken to create and strengthen the state sector in the economy, through the expropriation of foreigners and those who were considered collaborators of the occupier. The economy was being organized according to the principle of “economic centralization”, although private property still existed, of course under strict state control.

The regime approved and began to implement a series of ambitious projects, such as: construction of roads, railways, draining of swamps, which required large financial resources, but also extensive human mobilization. In this way, the communist regime created its own political and economic support layer. On February 21, 1946, the 5th Plenum of the Central Committee of the KPSH was convened, which discussed and decided on the future paths and developments of Albania.

In the Plenum, it was declared that in Albania, “a revolutionary democratic dictatorship of workers and peasants with the Communist Party at the head” was being established. According to the Communists, the system was democratic because it belonged to the whole people and it was up to the people to fight against the classes that were yesterday in power, the feudal and bourgeois, who still held important positions in their hands.

In this process, the task of the party was to make the masses aware of their new mission. The plenum thus officially announced the class war as the foundation on which the new state would be supported, this war, which turned into one of the most serious wounds for the entire Albanian society during the entire communist dictatorship.

The class struggle in Albania reached great proportions. Its object was not only the collaborators of the occupier, or the war criminals, but also the rich strata of society, the bourgeoisie, the nobility of the land, the chiefs of the Northern Highlands, and all those who did not approve of or lacked enthusiasm for the reforms that was undertaken by the new Albanian government.

Maliqi Swamp and the project for its drying

The Maliqi Swamp occupied a very large area of land and had become a source of malarial diseases for the entire area. The plan for its drying was drawn up in 1936 by the Italian engineer, Angelo Omodeo. The plan was indeed ambitious. It envisaged the opening and systematization of two canals, lower and upper, the systematization of the Devolli River and the Dunavec stream, as well as the construction of several main collectors.

At the end of this project, 4,500 ha of land were expected to be drained and another 4,500 ha to be rehabilitated. According to the experts of the time, Omodeo’s plan was quite detailed, as far as the works for the opening of the two canals were concerned, while for the rest, the project had general data and no necessary specifications.

In early 1946, the Ministry of World Affairs, based on Omodeo’s project, drew up a work plan for draining the Maliq swamp. According to Subi Bakiri, the political leader in charge of following the works to drain the Maliqi swamp, the ministry had not done a preliminary study on Omodeo’s plan, but had taken it for granted and had started the work, based on it. Time showed that a study on the project was very necessary.

It seems that Omodeo had not been very careful in the calculations for the implementation of the project. Thus, the project did not foresee that during the opening of the canal, rocky ground was encountered, and in some cases, the depth of the canal was not well calculated. A preliminary study of the project could have eliminated these inaccuracies of the initial project, but the Albanian government was in a hurry to start the works for draining the swamp as soon as possible.

The most likely were the economic reasons that prompted the Albanian government to undertake such an initiative, but propaganda and political reasons cannot be excluded. Freeing such an agricultural surface from water would give the region’s economy a breather, but at the same time it would convince people of the right policy of the new Albanian government.

With unwarranted speed, the Ministry of World Affairs made a rough estimate of the cost of the work, the labor force and the machinery and equipment that would be needed to complete the work. According to this preliminary plan, the draining of the Maliq Swamp was to take place within 180 days, starting on May 1, 1946. A small number of wage laborers would be used as the labor force, while the majority of the labor force would be volunteers. .

Likewise, a limited amount of motorized tools, such as excavators, motor pumps, etc., would be used. After reviewing this plan by the State Plan Commission, it decided that the entire project should be completed in 150 days, i.e. one month before the time requested by the Ministry. The commission had increased the number of volunteers who would be involved in the works to drain the swamp. Also, the overall cost of the project was reduced by almost 50%. At the end of the works, about 2,000 ha were expected to be freed from water earth.

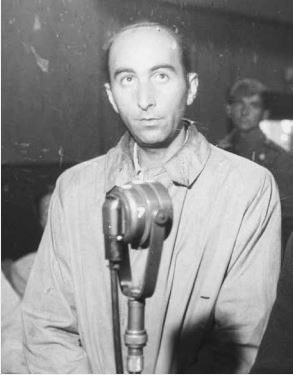

On April 15, 1946, the preparatory works for the construction of the Maliqi construction site began. On May 5, with a grand ceremony, the beginning of the works was officially inaugurated and, a day later, work began on the implementation of an ambitious project, which was expected to be completed on October 1, 1946. To direct the works, Abdyl Sharra was appointed, 35-year-old engineer. He was educated in Istanbul, at Robert College and then attended higher studies in Turin, Italy.

He had worked as a specialist in the Ministry of World Affairs during the Second World War. He then responded to the call of the Albanian government to mobilize the educated specialists of the country and was committed to the construction of several bridges throughout Albania. He was joined by a group of engineers and technicians, such as Eng. Vasil Mano, geometers Pandeli Zografi, Aleks Vasili, Italian Mario Guarnieri, etc.

It was soon realized that the project that Sharra had undertaken to lead did not depend only on his personal capabilities and abilities. He didn’t have a sufficient force of skilled workers to rely on, he didn’t have enough machinery to help speed up the work, and he had plenty of miscalculations that had to be corrected along the way. If you add to these reasons the incompetence and lack of experience of both the state administration and the local party administration, these made the pace of the works to be quite slow.

For this reason, in July 1946, the Ministry removed the engineer Abdyl Sharra from his position, to replace him with Kujtim Beqir. The 30-year-old had been one of the students of the Technical School of Tirana. He had studied in Vienna for civil engineering and was distinguished for his special talent in the field of engineering.

Kujtim Beqiri began work by revising Omodeo’s plan and, trying to correct all the inaccuracies and miscalculations found in the original project, presented an improved project for draining the marsh, which required additional tools and expenses, which were considered exaggerated by the local party leaders.

By September 1946, it was becoming increasingly clear that the draining of the Maliq marsh would not be completed in time. The top leaders of the SNP began to worry and press for higher rates.

The answer they received from the specialists was the same: the deadline could be met with an extraordinary workforce (according to engineer Konomi’s project, up to 10,000 workers would be needed per day), with more machines and with greater financial funds, which were impossible to tune.

On September 6. a Control Commission, specially set up to control the works for draining the swamp, is sent to the Maliqi construction site. In a marathon meeting. the problems that emerged during this work were discussed at length. The minutes of the meeting are a clear evidence of the innumerable shortages and difficulties that Maliqi’s team of engineers and technicians faced.

On September 30, 1946, the final conclusions of the control group were discussed at a meeting at the Ministry of World Affairs. The control group did not fail to point out, the very optimistic forecasts of the ministry, on the productivity of manual workers, machines, financial cost and, finally, and the wrong forecast for the completion time of the works.

The control accused the engineer Sharra of sabotaging the works and demanded the arrest of him and the Italian technician, Mario Guarnieri11. He also asked for a written warning to be given to the engineer Aleks Vasili, the geometer Pandeli Zografi and some others.

The trial of the engineers of the Maliqi Swamp – a process based on suspicions, but not on facts!

The conclusions of the Special Commission came later in time, as the State Security bodies had preceded them. On September 30, 1946, they arrested the engineer Abdyl Sharra, the engineer Aleks Vasili, the surveyors Pandeli Zografi and Mario Guarnieri, the wife of the engineer Vasil Mano, the Croatian Zyrika Mano, as well as the workers Jani Vasili and Anastas Risto, whom they accused of being couriers of the first ones. Their arrest was the first step in a large scheme of arrests that would follow throughout the month of October.

The bodies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs did not need much evidence, it was enough for one of the arrested to mention a name during the violent investigative process and the chain of arrests was extended. Thus, the engineer Vasil Mano, the geometer Mihal Stratobërdha and the Italian accountant, Eugenio Scaturo, were then arrested, to close this phase, with the arrest of the engineer Kujtim Beqir, on October 24, 1946.

Pressed by violence during the investigative process, the accused almost all accepted the charges made. They were accused of having cooperated with the member of the American Civil Mission in Tirana, Harry Fultz, to sabotage the drying of the Maliqi swamp, with the aim of discrediting the Albanian government.

According to the investigation data, “the (sabotaging) work was divided as follows: Engineer Sharra undertook to sabotage the work in the canal, not starting the work according to the planned plan, by using excavators, not at the necessary work points, by placing of volunteer forces, not in the right places, with the loss of time and yield, with the embellishment of the escarpments.

Aleks Vasili took it upon himself to sabotage the work in the quarry, spending a lot of materials, such as black powder, etc.

The geometer Pandeli Zografi took it upon himself to sabotage the work in the decoville, in order to delay the connection of the canal with the quarry, which would also apply to the obstacle of the workers in the quarry. Eugenio Scaturo, would sabotage the canteen meals of the workers and specialists, in order for them to remain dissatisfied and create hatred towards the government.

Engineer Vasil Mano took it upon himself to sabotage the work on the construction site, by not setting up the workers’ barracks quickly in order for them to get bored and run away, not to force the technicians to repair various machines that might have defects; he would try to take material out of use, even with a few defects”.

On November 8, 1946, in the “National” Cinema, the trial was opened in charge of Maliqi’s engineers and technicians. Outside the cinema building, large loudspeakers were placed, through which the citizens of Tirana followed the progress of the trial. By special order of the Central Committee of the KPSH, the workers of the Maliqi construction site had to follow the trial with special care.

The indictment pointed out that: “All the defendants above, who had different responsibilities for the drying up of Maliq and who had connections with external elements, are accused of having committed serious sabotage, causing great damage to the state. It is also specified that; to carry out these sabotages, the defendants held secret meetings, that they reported to foreigners about the works and that they followed their orders to carry out the sabotages”. Memorie.al

The next issue follows

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)