By Astrit Jegeni

The first part

Memorie.al / Ahmet Jegeni, a senior official of the Enverist regime, held numerous party and power positions in that political system, among others, he was the director of the port of Durrës for many years. Later, he started working at the Ministry of Foreign Trade and was appointed Secretary of the Party Organization of this Ministry, until he was arrested on the charge of “hostile activity” with the so-called group of Kiço Ngjela and his friends, a charge that he did not accept for almost a year. . The violence exercised in the communist investigation broke him and he writes this memorandum, accepting the cooperation with the accusation, which he did not accept at first. In extreme personal physical and psychological conditions, he describes in writing himself, his colleagues, his family members according to the desire and the communist moral political mindset.

In my childhood memory, I have an image of a man of average height, slightly built, well-dressed in clothes bought outside Albania, dignified. On the street, and when he happened to meet my father, he greeted him with his head, but always with the appropriate distance and coldness, which stemmed from the fact that they belonged to two different political strata and opposite social positions. They were almost the same age, they were cousins, and they had been together in the partisan detachment of Dibra e Madhe, with Commander Haxhi Lleshin.

My father has shown me moments from the surrender of the Italian army after the capitulation of Italy, and it was Ahmeti, who got into a “Caro-armato”, a car reinforced with thick sheets, and went himself to the Italian barracks of Dibra e Madhe, to negotiate with the Italian command there. My father begged and asked him not to go, because the Italians would kill him, but he was not afraid. After a few hours, the Italians accepted the agreement with Ahmet, they with their personal weapons and daily food, released their barracks to the partisans and headed towards Peshkopia.

In the endless conversations of my tribe, Ahmeti was treated with care, thanks to the fact that he was a high-ranking communist functionary, I believe it was Jegeni, who had the highest post in the communist regime, the absolute majority of Jegeni were anti-communist. Another Jegeni with communist beliefs and who had high party and state functions was the son of my uncle, Eqerem Begut, Besnik Jegeni, but he had functions in Macedonia and we actually knew little, or nothing, about his real social weight.

However, Ahmeti was seen with sympathy, as a man who knew how to maintain a reasonable attitude of respect towards his tribe, who were generally labeled “reactionaries” by communist propaganda and mentality. Only in cases of death, Ahmeti appeared for the occasional visit, and these were very rare. We were in political exile, when we got the news that Ahmet was arrested, my father expressed regret, but that was all. He didn’t take it in his mouth, neither for better nor for worse.

Later, when we returned from exile, with Pranvera, Ahmet’s sister, who was in Tirana, we had endless and long conversations about Ahmet and his relationships with his family, about his mother who lived with Pranvera, and not with his son, his wife from the Strazimir tribe, Dhurata, sister, brother, who lived outside Albania, the nearby tribe, and my perspective on Ahmet changed.

I remember Mitrushi, his brother-in-law, “Hundelesh”, that’s what I called him because he had hair on his nose, a charming, cultured man, quite entertaining and very modern for the time, when he came to our house, he created a pleasant atmosphere. It was a pleasure to listen to that man. Unfortunately, Ahmet’s relations with his wife, mother and sister were, according to Pranvera, unpleasant and problematic. However, various acquaintances and strangers I met, when they asked me about my last name, the first subsequent question was; what is your relationship with Ahmet?

They all spoke well of him. When I got hold of this memo and read it, I was stunned, I didn’t like it and I was disappointed by Ahmet’s personality, I was surprised. Ylli Selenica, a good friend of mine, who was a political prisoner, told me, when he was alive, not to judge people from the data of the communist investigation, because it was a very violent body of justice and few people could to bear it, they were forced to accept whatever was imposed on you, it is enough for the torture to stop. However, I was very hesitant to make the memorandum public.

Morally, I did not like the figure of Ahmet. Reason became a person who knew Ahmet to change his mind. In a debate with me, he spoke with superlatives about the figure of Ahmet Jegen, taking him to the limits of singing hymns. Annoyed and tired of the lack of a sense of reality for the human figures that people have in their subconscious, I decided to publish this memoir. What I am publishing is a small part of this memorandum and, perhaps, the most “famous” of the entire memorandum, which for me is extremely inappropriate, almost on the verge of shame.

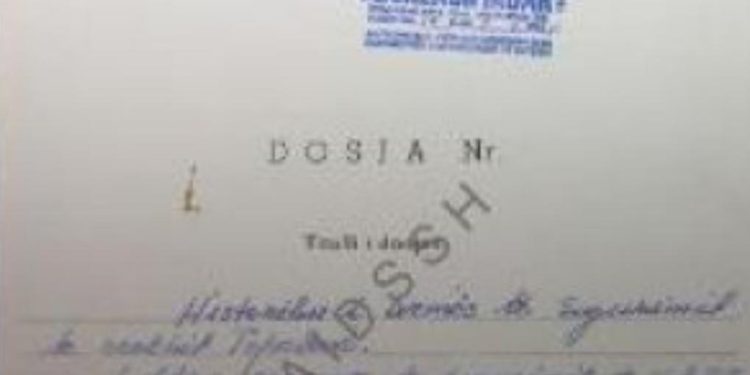

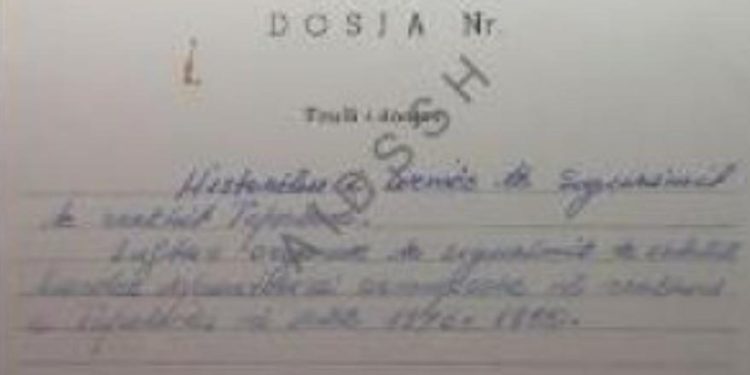

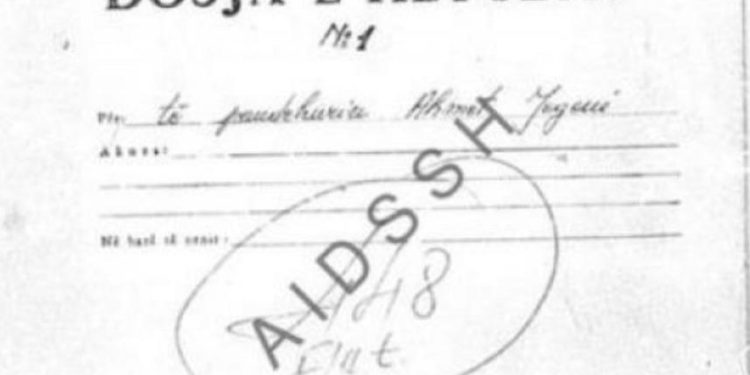

The memorandum of Ahmet Jegen, made in the Enverist investigation, in the form of a manuscript, consists of 184 pages, it was written under conditions of violent physical and psychological dictation to the investigator. It is written on A-4 paper, of poor quality, locally made, written in black pencil, on both sides of the paper, most of the handwriting is in pencil about 80%, the rest in blue and red pen, a relatively fine handwriting, but clearly legible and free of spelling errors.

During the investigation, a part of this material, about 10-15%, was typed by the employees of the Investigation and given to read by Ahmet Jegeni, who in some places interfered with his writing, to clarify the sentence and to too self-willed, to burden himself more before the law. Indicator of psychological and physical surrender to the violence that was done to him during the investigation.

During its typing, some words were adapted from the dialect of Dibra e Madhe in literary language, but without changing the meaning of the sentence. Some expressions and words are not correctly transcribed, but they have not deformed the logic of the sentence. It should be noted that for a long time, about a year, Ahmet Jegeni did not accept any of the accusations of the investigators, but after many months of physical and psychological violence, Ahmeti surrenders and accepts the accusation.

“For hostile activity” and begins to write his self-denouncing memoirs, which I believe were written not because he felt regret for his political and state activity, but because he completely surrendered from the great physical and psychological pressure, he hoped that he will come out alive from the hell of the communist investigation. He could have acted differently, but he didn’t. In reality, most of the political prisoners from the communist regime did not withstand the physical and psychological violence and surrendered and signed what the communist investigators wanted.

The handwritten manuscript is dated 4.10.1976 and is signed by him, while the typewritten material has the same date, but is not signed. We must note that there is a discrepancy in time between the date of his arrest and the date when Ahmeti started writing these manuscripts. Ahmet Jegeni died in the investigator. According to medical records, death was caused by a heart attack. I am inclined to believe that his death came from the unbearable living conditions of the investigation and physical and psychological violence. His case did not go to trial. Legally, Ahmet Jegeni is considered innocent.

We are giving them to be read as they are written in the typewritten original, contrasting each line or proper name with the handwritten original. The memo for me is interesting, that apart from the general historical character that we are informed about, in this interesting memo, is the information we get from the very good trade relations between Albania and Yugoslavia. At this time, Yugoslavia was the second partner after China, in Albania’s trade volume, it should be noted that the Albanian-Chinese political and economic crisis had begun to have its effects on the country’s economy; the ironic fact is that we have a report of obliquely with Enverist hostile propaganda for Titism and very good trade relations with Yugoslavia.

The handwriting of the defendant Ahmet Jegen

I was born in 1920, in Dibër te Madhe, I come from a well-known family in the city and its surroundings, of rich origin (manor), we had land and a house, a living thing both in Dibër (Yugoslavia) and on the Albanian border -Yugoslav), just like all the people from Dibran, our family was destroyed by the Serbs, and their houses were burned, the grandfather was strangled by them, with a telephone wire, the father of persecuted, so in 1930, we moved to Albania (Durrës).

I continued high school (royal school) but in 1933, the father dies and the family is forced to live, return to Dibër (Yugoslavia), while I remain here, to continue school. In 1935, I went to study in Italy (military school), in Naples and 1937-1939, at the Military Academy. (Turin).

At this time, the occupation took place, and although I did not have any specific political orientation, the idea of patriotism came to me, I did not agree with the occupation, I asked to return to my homeland, I did not swear allegiance to fascism (which was organized on this occasion with all former Albanian military students studying in Italy), as a result I was imprisoned and interned on the island of Ventottene (Italy), where I lived from 1939, until September 1941. Here I came into contact with the Italian communists, who began to instill in me initial communist feelings and preparations.

Other Albanian internees came to the island, as well as others from Shkodra (from the Communist Group). In September 1941, after the term of the sentence ends, I return to Albania, go to Dibër te Madhe, near my family (I had my grandmother, mother, two sisters and a brother) and after being arrested for anti-fascist activity in 1942, after my release, in September 1942 , I go to the partisan detachment of Dibra (Commander Comrade Haxhi Lleshi and stay in the units of the National Liberation Army, until August 1944, where by order of the Party, I came to power, then in 1946, I was assigned to work in Tirana, later in Durrës, then in Tirana, again in Durrës (where I stayed for 18 years) and in 1971, again in Tirana (until August 1975), then in Tepelena, where on 4.6.1976, I was arrested.

As I said before, I, at the beginning, did not have any specific political orientation, in Italy I read newspapers and in general I was inclined to follow, through the press, international events, but I was not able to understand them, as rather as a curiosity. I read with interest the articles that were published in Italian newspapers about the Soviet Union, among other things there was a lot of talk about religion (I had no religious inclination since I grew up away from my family and also), a lot was written about Stalin, who was presented as a strict man.

Based on this, I did not maintain friendship with Albanian students who showed sympathies for the Soviet Union (in Naples, Kadri Hoxha, in Turin Skënder Çaçi, Hamit Keçi and I did not maintain a hostile attitude towards the Soviet Union, or friendly towards fascism, but rather as indifferent to political issues, I focused on my studies so that I could do well and finish school.

Since he had given me a scholarship, I had sympathy for Zogu (not that I understood the political character of the regime, but only because he was at the head of the state). In Italy, I saw many cities and to be honest, I was impressed by the development at that time, and I had sympathy and good memories for the country and the people.

On the occasion of the occupation of Albania, the hatred towards fascism (the social and political character of which I did not understand) began, as an occupier, but I kept good memories for the people and Italy itself as a country, I had this even during the War, after the liberation and this also influenced my work at the Ministry of Trade, when in September 1973, I was given the direction of free currency trade.

Thus, in my meetings with the Italian delegation, with those of the embassy, who followed commercial issues, I was predisposed to increase trade with this country, this is due to the fact that until then, this country occupied the first place in trade with Western Europe with we, on the other hand, found that the Foreign Trade Enterprises, as well as the leadership of the Ministry, had this opinion.

In Venttotene (internment in Italy), I spent more time with Skënder Çaçi, Xhemal Punavina, Abdyl Këllezi, Qazim Kapisizi. With Abdyl Këllez, we studied the Italian labor movement and parts of Marx’s chapter (value, surplus value, etc.), I had the same educator, the Italian communist (Pietro Secelie and Pietro Griforçe). Of course, what we learned from them, I repeated with Abdyl. However, I still didn’t have a complete communist conviction, because I didn’t understand many things and I still had nationalist feelings.

Even for the Soviet Union, many things certainly became clearer, but I still did not understand what it represented in the social aspect, as a state power, its importance was understood with the Nazi attack and I wanted the Soviet Union to definitely win , as it was understood that this fact was also related to our country.

I don’t remember any particular issue about Abdyl Këllezi, I don’t remember political conversations or interpretations or political situations being made to me by him. Ay also socialized a lot with Xezmi Delli (she stayed with him a lot and almost constantly, as well as with his family when he came to visit). His cousin (merchant) came to Abdyl twice; it was the same with Shefqet Myslin (he came with those from Shkodra, in Venttotene).

In 1949 (September, when I went to Belgrade, and the Germans left there were transiting to Albania), Shefqeti performed the function of translator (only 1 day) and I remember Ventotena and asked how Abdyli is doing, I later I told this to Abdyl Këllez, because he is his brother-in-law. Abdyli welcomed this. When I returned to Albania, I went to my family, there I met Nazmi Rushiti (whom I knew in Venttotene) and continued to work under his direction.

In Dibër, I also met many young people from Dibër, such as Xhafer Kodra (later he was a translator of Tempo, after 1948, Minister in Macedonia, later imprisoned by the Yugoslavs, Met Kërliu (apparently with functions in Macedonia, I saw him once in September 1949, in the hotel “Moska”, Belgrade and he told me that he continued his studies there), Azmi Muça, Jashar Hemija, Lutfi Rusi, etc.

I became friends with them and during the time I lived in the city, I associated with them and developed anti-fascist propaganda. I heard that all of them were with the Movement and at the same time later served Titism faithfully, at this time of course according to the directives of the Party, we were developing a propaganda of the common war with the Yugoslav peoples, with those anti-Serbian feelings that I had before (from the previous sufferings of the Dibrans and my family), I left them aside, even speaking harshly to some members of my tribe, who showed doubts in this war of common. In this way, I began to sympathize with the Yugoslavs.

During the National Liberation War, I, in addition to the Dibra persons I described earlier, whom I met again in September-November 1943, when we liberated and kept Dibra the Great, in April-May 1943, I also met Veli Deva, who was transiting from Albania to Kosovo. I stayed with him for 4-5 days in a village, because I was wounded and I did not have any special conversations, except for those that were held in our company by the partisans.

Like the war here, and in the world, etc., a matter of time, there was a lot of talk about Kosovo, Dibra, etc., or how it will be done, but it was concluded that we were fighting for a goal; therefore it was not a problem of time. During the National Liberation War, I have never been separated and I have never met other people or Dibras who lived in Yugoslavia. One night (October 1943), Miladin Popovici was at my house in Dibër with Mr. Hajj.

During the National Liberation War, I had made it my duty to fight fascism for the liberation of the country, I know that I did not fight badly, but I was not able to predict what the situation would be after the war, of course I had faith in our victory, but what would happen to our concrete destinies and the state, our relations with our neighbors, mutual interests, etc., I did not understand how and to what extent.

I had also decided that despite the fact that I had family and wealth in Dibër te Madhe, I would stay in Albania because I was Albanian, I had grown up here and I had fought here and it was up to me to serve this country.

When we were in Dibër in September-November 1943, I had listened to some conversations that Sh. Haxhi and Tempo regarding the relationship, but we were not told anything in detail, I learned about them only later when these issues were announced, so I have not had conversations of this nature with anyone and no one has talking to me about such issues, I have continued to talk about common interests, the same goal between us and the Yugoslavs. Memorie.al

The next issue follows