By Prof. Nor. Dr. Sonila Boçi

Kristi Kolce

The second part

-Petraq Peppo: intellectual and historian in the face of communist indoctrination –

Memorie.al / Mihai Botez, a Romanian intellectual who sought political asylum in the USA in 1988, speaking about the life of an intellectual in a dictatorial system asserted: “It is sometimes said that an intellectual who lives under a communist regime must definitely choose between being ‘the man of the court’, or a dissident. This is an oversimplification. Accepting the social contract (of the communist regime) does not automatically mean that you became a “court man”. Because, under communist dictatorship, there is a sad but true concept called ‘the art of survival’, even in a dignified way, which involves a combination of calculated submission, self-controlled criticism, tactically maintaining a profile of low and intelligent use of opportunities. Certainly too many Western intellectuals, these strategies seem strange, even repulsive. In principle, I am ready to agree with them, expressing my wish that they never need to learn this art”.

Continues from last issue

Petraq Peppo and the challenge to adapt to the Marxist treatment of history

Thirdly, he never expressed any opposition to the regime. Fourth, his fields of study, especially his knowledge of Greece’s early relations with Albania, made him indispensable to the regime, as it had to confront Greek claims and reaffirm independence, borders, and the political system. In other words, Petraq Peppoja was one of the few intellectuals educated in the West, whom the regime would have to trust.

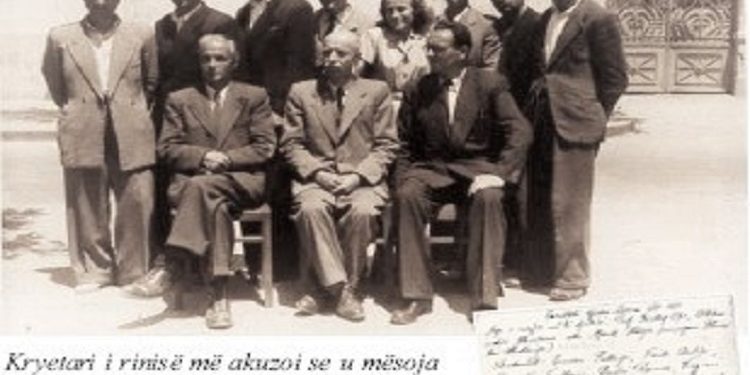

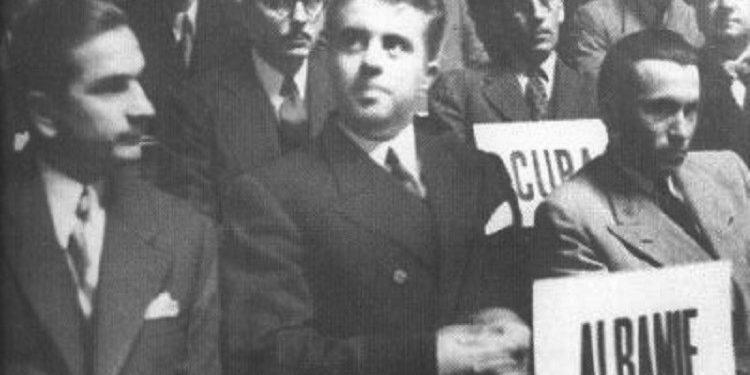

In July 1946, the name of prof. Peppos, would be among the two historians who would be part of the delegation that would be sent to the Peace Conference in Paris, to defend Albania, in the face of the territorial claims raised by the Greek government. Leonidha Pepo claims that it was Enver Hoxha who would choose Petraq Peppo. In the Archives of the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, there are many materials of a historical nature, which do not have the names of the preparers, but since Aleks Buda and Petraq Peppo were the only historians of the delegation, these materials must be the fruit of their work.

When the Peace Conference began work in Paris on July 29, 1946, the Greek government had already received a promise from the British and Americans that its claims against South Albania would be heard. This certainly worried the Albanian government, even though it had received notifications that the Conference would, in principle, only discuss treaties with the defeated states. On August 3, 1946, Greek Prime Minister Caldaris (Konstantinos Tsaldaris), who headed the delegation, presented the issue of “Northern Epirus” to the Peace Conference.

In the speech of the Greek Prime Minister, the same accusations were summarized, which the Greek government had long articulated in various offices. He spoke about the historical Hellenic character of “Vorio-Epirus”, about its Hellenic population that, even after undergoing a process of de-Hellenization, had still preserved its Hellenic character and consciousness. Among other things, the Greek Prime Minister emphasized that; “the state of war, which exists between Albania and us, must go to a natural and just conclusion by passing Vorio-Epirin to Greece”.

On August 21, 1946, it was allowed to present the position of the Albanian government before the Peace Conference and its representative. Enver Hoxha, as the head of the delegation, explained the reasons why Albania should be accepted to have its say in the peace treaties. A large part of Enver Hoxha’s speech was focused on refuting the accusations presented a few days ago by the Greek Prime Minister, according to which there was a state of war between Albania and Greece.

While communist politicians held talks with the victorious powers of the war, showing them that Albania was a victim of Mussolini’s Italy and had never threatened neighboring countries, the historians of the delegation were engaged in public debates with Greek historians and press conferences, refuting theses for the so-called; “Vorio Epirus”. Leonidha tells in detail the history of those days and the debate that took place in that hall: “It is Greek land – it was the most persistent claim of the Greeks. – All archaeological excavations in Apollonia or even in other places prove this. Many old writings in Greek, old Greek coins were found there…”!

“Then based on this logic, – the Albanian historian had answered them with perfect French, – you, the Greeks, and the French, should also give you Paris, they should also give you this hall, where we are talking, as in some old churches, not far from here, there are plaques with inscriptions in Greek, but also old Greek coins…”! While the non-consideration of Greek claims by the Peace Conference was a matter that belonged to the decision-making of the Great Ones, the two Albanian historians, Petraq Peppo and Aleks Buda, made a valuable contribution to show the lack of real arguments of official Athens on this issue.

At the end of the Conference, Albania was recognized as a “friendly power”, thus placing it on the side of the winning states of the Second World War, which signed the Peace Treaty with Italy. The recognition of this status made the demands of official Athens invalid and, as time showed, they were no longer examined in any international forum. The dignified presentation at the Peace Conference in Paris must have had a significant impact on the later career of Petraq Peppos. In 1947, when the Pedagogical Institute was opened, the first institution of higher education in the country, Peppoja was appointed there as a lecturer.

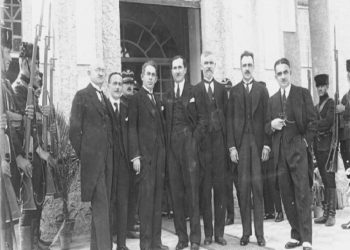

According to his biography, Peppos had to do an extraordinary job as a teacher at the Pedagogical Institute. He taught students the courses of Ancient History, History of the Middle Ages, and History of the Soviet Union which, in the absence of texts, he had to prepare himself. At the same time, he is one of the founders of the Institute of Sciences (January 1947), being one of the members of its Assembly. In the rush of the communist government to set up its own institutions of science and higher education, in the absence of educated people, it was not an unusual situation for one person to work simultaneously in both institutions.

The Institute of Sciences, like every other institution in the Albanian state, run by the NPSH/PPSH, was under strict political control. Every year, the activity of the Institute of Science was examined carefully and in detail in the high party forums, in the Political Bureau or in the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the ALP. At the head of the institution was placed the Minister of Justice, Manol Konomi, who was actually an intermediary between the governing bodies of the scientific institution and the highest party leadership. Some issues of the scientific journal, the Bulletin of the Institute of Sciences, had Stalin’s picture on their frontispiece; all these details clearly point to the control and ideologization of Albanian science.

Beyond political control, researchers had to face the obligation to support Albanian science, based on Marxist-Seleninist theory. In the analysis that the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the ALP made for the activity of the Institute of Sciences during the years 1948-1949, two issues were emphasized the most: first, it was emphasized that “Scientific studies carried out on our country by foreigners, have not been directed and do not respond to our goals and needs, to systematically know the country in terms of its opportunities and economic and cultural development. They can only be used to facilitate our studies in some way”.

For this reason, the principle that the Institute of Sciences should follow in its path is to put the results of its scientific activity at the service of the people, to raise the level of its material well-being and its cultural development as soon as possible. “. Secondly, it was noted that; “The Institute of Sciences has neglected the important problem of education and re-education of its cadres and other people of science with the ideology of Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist science and has not tried to raise the various scientific problems in the ideological field, so that the debris of reactionary and bourgeois ideology could be combated with the appropriate efficiency in the people of science and dialectical and historical materialism would become the platform of every branch of science.

The task that was emphasized to the Institute of Sciences by the senior leaders of the communist ALP was to dedicate themselves with all their forces to their communist education. Until 1952, when the first students graduated from the Soviet Union and some other countries of the Communist East returned home, the regime had no choice but to entrust the work of building scientific institutions to people who were educated in the West, although some of them did not believe in Marxist ideology. Petraq Peppo, was one of these, constituting a very interesting case study.

As we mentioned earlier, Peppoja was apolitical. He made no attempt to occupy state positions, or to show marked devotion to the regime. While she did not hesitate to always speak her mind, Peppoja made every effort to assimilate Marxist ideology. In 1955, he enrolled in the Marxist-Leninist education courses held at the “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin” Party School and completed it, with very high results.

The reasons why P. Peppo, at the age of 52, made the decision to attend Marxist-Leninist education courses are difficult to document! But we can make an analysis based on the data we have, on his activity as a member of the Institute of Sciences. For a researcher of history under the communist regime, the knowledge of Marxist theory was one of the essential conditions to continue the work, regardless of which periods of history the studies were focused on. In 1948, work had begun on drafting an official text on the History of Albania, in which Petraq Peppoja was designated as one of the co-authors.

He would find it very difficult to be successful in discussing this text if he did not support it in the theory of dialectical and historical materialism. The fact that he enrolled in the Marxism-Leninism courses, exactly at the time when the first part of the text, where Peppoja was the author, was in the process of discussion, is a plus argument in this analysis. Even later, when Peppoja, already in retirement, would teach young researchers how they should walk the path of scientific research, in addition to the scrupulousness with which they should see the document and the accuracy of the translation, he would not forget to order them ; “sprinkle a little more dust of Marxism-Leninism”, so that the studies would be published.

Another reason to seek integration in the new regime may be the need to be heard more. In the first years of the establishment of the Institute of Sciences, Petraq Peppoja was one of the people who was not afraid to speak his mind. In the 1948 annual review, he criticized the management for a lack of transparency. He had no hesitation in proposing studies on topics that were considered difficult and problematic, such as: studies on the Pelasgians, or on Albanian antiquity.

There are not a few cases that have raised important issues for the relationship between science and teaching, as was the case at the meeting of the Institute of Sciences in 1952, where; “comrade Peppo raised the issue of the cooperation and assistance that the institute should provide to the Ministry of Education regarding the compilation of textbooks and the organization of expeditions, in order to help the students of the Ministry in their original works”.

All his proposals fell on deaf ears, both of the leaders of the Institute and of the senior party leaders. This may have forced the ambitious researcher to look for a way to find a way to feel somehow more involved in the decision-making of the new regime.

The years 1947-1954 can be considered as years of adaptation of the historian educated in France, with an ideology that he did not feel fully his own. During his scientific activity, prof. Peppo has left us very important works for the history of Albania. The translation of documents from old Greek, the help to bring the testaments of Iljaz Bey Mirahori and others into Albanian, provide important information about Korça under the Ottoman rule, but also about the organization of economic and social life in that period.

Especially the collection of documents, the codices of Korça and Selasfori and the codices of the villages of Korça, an early passion of his, are a very valuable contribution to the history of Albania.

As Prof. he said Peppoja, the history of Albania was written based on foreign archives, the documents that he spent his whole life provided what was missing, the local document and a different perspective on the history of Albania. All these studies are the fruit of an extraordinary work, with a lot of passion and dedication. Describing the archives as “science laboratories”, Peppoja, even at an advanced age, did not stop visiting them.

Even, appreciating the “enrichment of patriotic work archives”, since “they (archives) help a lot in the development of scientific work”, he took special care in collecting many historical documents, going himself wherever they were: bakaj , warehouses of former merchants, streets, small markets (where he collected papers, deeds, merchant notebooks thrown away full of moisture, that were moldy or rotting), etc., what he considered as a “small civic service”, which he performed in the capacity of “a simple and small workshop of historical science”.

Leonidha remembers very well the long hours of prof. Peppos, at the work table. “My father was a champion of using archives,” he emphasizes, “he worked long hours, almost 8 hours a day, and of course when he came back from work, he would be working again.” He couldn’t imagine staying a day without studying, … no one entered our waiting room, as soon as my father returned from work, he resumed his studies, sitting cross-legged, the whole room was covered with the materials he studied and wrote” , he says laughing.

His professional and accurate translations suffered, unfortunately, from the Marxist ideologies imposed on historians. According to the researcher of the Middle Ages, Andi Rëmbec, parts were removed from the translations, which conflicted with the ideology of the time. It seems that prof. Peppo made some compromises in order to pursue his passion for history. For his contribution, he was appreciated by the authorities of the time. So in 1950, he was awarded the “Memorial Medal”. In 1958, he was honored with the “Class II Work Order”, while in 1962; he also received the “First Class Work Order”.

In 1981, he was honored by the People’s Council of Vithkuq Village, (1981), with the title “Honorary Villagers of Vithkuq” (together with his wife Mrs. Marika Peppo], with the motivation; “For the persistent work in building, enriching the museum, in the preparation of the scientific session on the history of Vithkuqi, as well as the development of conversations and meetings of a scientific nature with the people and youth”.

He did not stop his research work, even after he retired in 1968, insisting that his contribution be recognized and appreciated by the state. From the research in the Central State Archive, several letters exchanged between him and Enver Hoxha have been found, through which he asked him to help him to be awarded the Republic Prize (1974), or to receive the title of Professor (1972). .

“I have living forces, – Peppoja would write to Enver Hoxha, – I have the will to work, time has not defeated me yet, that’s why I asked the Institute of History to hire me as a retired professor”. In a letter addressed to Enver Hoxha, September 1971, he would write “…I ask the Directorate of the Institute to propose me to the High Certification Commission, to grant me the title of professor, putting me in the ranks of professionals”.

While a few years later, specifically in 1974, he would write to Enver Hoxha again; “For your information, I have the honor to send you the copy of the prayer addressed to the Institute of History, on the basis of which, based on my enthusiastic activity for the benefit of education and culture in the people, I will be honored with the Prize of the Republic”.

These very letters and the answers that come from the apparatchiks of the Central Committee of the ALP are another proof of the strong state control over science. They did not want to consider the request of Petraq Peppos, but they ask that he be given a careful answer, respecting his advanced age. As if to compensate for the lack of recognition of merits in the field of studies, Peppoja received praise for his pedagogical activity.

On the occasion of his 70th birthday, the Presidium of the People’s Assembly awarded him the “Order of Naim Frashëri, First Class”. A year later, he is finally awarded the scientific title; “Senior Research Associate”, today’s equivalent of Associate Professor. In 1984, he was honored with the title “Teacher of the People”.

Peppoja passed away on December 14, 1989. After his death, he was honored with the title; “Honorary citizen of Korçë district”, with the motivation; “Prominent figure of national education, patriot, historian with extensive, valuable contribution to the development of Korça and national culture”, from the Korçë District Council (2003), as well as with the title; “Golden Emblem of the City”, with the motivation “Outstanding intellectual, part of the Korça High School, who with his scientific and social activity made great contributions to Albanian culture”, from the Municipality of Korça, by decision of the Municipal Council, in within the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the opening of the National High School of Korça (2017). Memorie.al