By Prof. Asst. Dr. Albert P. Nicholas

Joana Doda

The first part

– Anthropological view, on the persecution of scientists during the years 1945-1955 – the case of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri, the observer of communism –

Memorie.al / The case under consideration is subject to a multi-level research methodology, which is dictated by the personality of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri. After studying in Austria, engineer Gjadri had a five-year work experience in the Soviet Union. Based on this data, we will observe some anthropological dynamics of the relations between “socialist” and “capitalist” science. The influence of the Austrian study experience, the work in the Soviet Union and later in Albania, lead us to look closely at the cultural dynamics of engineer Gjadri’s behavior towards the issue of work remuneration, under the perspective of economic anthropology.

In this light, the archival documents of the ALP will be accessed, on service issues, and a comparison will be made between Lenin’s approach to the Soviet Union, on this issue, and engineer Gjadri’s debates, on the same argument. This is due to the fact that the Albanian communist regime, in the years to which the study refers, is mainly based on the Soviet methods of involving intellectuals in the construction of socialism.

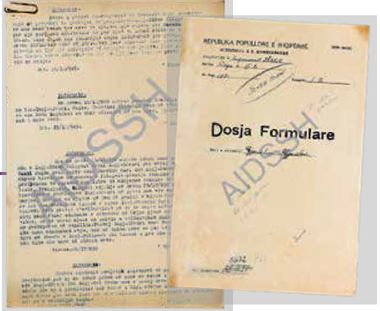

Archival research on the observation of engineer Gjadri as a “potential enemy” of the regime constitutes very important methodological support. In this part of the study, the dynamics of observation, espionage, the inevitable cultural dose of rumors and the impact these activities have on the life of Gjadri will be analyzed from an anthropological point of view.

Finally, in the following part, which is also the main part of the study, the methodology of historical anthropology will be followed, through which archival documents are analyzed in the light of the cultural elements present, which give us the necessary support to deepen in the analysis. In this perspective, the behavior of the regime towards Gjadri’s “technical skills” will be looked at. Of deep anthropological interest for our study is the frequent encounter in the archives of the term “usage”, to refer to persons. In our opinion, this is clear evidence of the reduction of the human being to a tool, to an object, which also paves the way culturally for a persecution, which is even regulated by law by the regime.

Due to the anthropological nature of the study, a part of the analysis will also be devoted to a book by Gjadri, published in 1942, in the German language, ‘Letters to my dying wife’. Throughout the study analysis, the case of engineer Gjadri will be analyzed by proving, through his history, the similar or common elements that the communist regime had in the violence it used against Albanian intellectuals and scientists, with the Soviet model as a point of reference.

Entry

After the end of World War II, a regime based on the dictatorship of the proletariat was established in Albania. The governance model supported by the Albanian Communist Party would be socialist, following the Soviet one. In the light of countless and strong persecutions, it can be said that Albania turned into a big prison.

The rise to power of the Albanian communists is still shrouded in a mystery and many studies will be needed to highlight the tragic weight of the historical period that goes from the end of the war until 1991. The dominant elite in the Albanian Communist Party, which was prepared and imposed by the Yugoslav communists. This elite consisted of people not very culturally or scientifically prepared, but hungry for power, above all ruthless to everyone: ready to kill anyone and at any moment, so that they could keep power.

In this cultural political climate, the dictator strongly supported class struggle, on the Soviet model. The created climate was really non-accepting, for those who were not obedient to the authorities. A statement of the dictator creates a clear idea of that situation: “You wash your face when you come back from work and clean yourself. Here, it is the same with Bolshevik criticism and self-criticism; it cleans up people’s flaws and mistakes.

You cannot live in a room with dust and dirt, but take the broom and sweep these. This is how Bolshevik criticism and self-criticism works; it cleanses the people, cleanses our Party, cleanses our power and our country from…’fleas, speculators, from scumbags…’ – as Lenin calls the bad people who are smuggled into our ranks. The party tells you to keep your eyes open everywhere”.

The class war and communist persecution affected all layers of society. She was very harsh, especially against intellectuals and scientists who were educated in Western countries. For the intellectuals, Enver Hoxha would say: “It is necessary to shake the intellectuals from the bourgeois ideology and arm them with the Marxist-Leninist ideology.”

Communist regime. intellectuals who could think differently from the official dogma he saw them as a threat to the rise and consolidation of power. This caused the majority of the intellectuals of the time, with the coming to power of communism, to be accused of; saboteurs, with arrests, internments, torture and shootings. But even against those intellectuals who were able to continue practicing their profession, the pressure was not small. Against them there was constant surveillance, as long as the intelligentsia was seen as a threat to power.

Enver Hoxha’s orders were always for binding every person with the Marxist-Leninist ideology, especially people of science. One of the most important directorates of power, such as the Directorate of Agitation and Propaganda, served for this purpose: “You, comrades of the Directorate of Agitation and Propaganda of the Central Committee, have nothing to do with clothes, or with cars, nor with other materials and, even with frames, that the institute needs; you should be interested in implementing the Party’s line in the Institute of Sciences”.

The attention of the regime towards the intellectuals coming from the western study experience, remained in the conviction of the communist power, that science has a deeply ideological and moral character. So we have good “socialist science” and bad “capitalist science”. This ideological conviction, typical of the communist elites, came from the reasoning that morality and science are very interconnected, therefore a good science educates a good morality and vice versa.

“Socialist science” was identified with Marxist-Leninist ideology and the latter, according to Marxist ideologues, was able to provide solutions to every scientific problem. The identification of science with ideology was so intense that even socialism was called “scientific socialism”.

“Marxism-Leninism is the science of the laws of the development of nature and society, the science of the revolution of the oppressed and exploited masses, the science of the victory of socialism, the science of building a communist society. Therefore, our Party, as a Marxist-Leninist party, from the first days of its organization, has paid special attention to the ideological education of its members”.

In spite of this, “capitalist” science does not have this strong ideological character and does not require the overthrow of economic and social formations by violence. It also often has its dogmas and “sins”, but it does not claim to be “the science of totalitarian power”. Even in its most aggressive versions, as in the case of the founding of the current of positivism, by A. Comte, it is still presented as an alternative, not as violence.

Engineer Gjovalin Gjadri, observer of communism

Through this study, we seek to bring to light the history of surveillance and persecution of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri. Engineer Gjadri, was born on July 2, 1899, in Shkodër. He was the son of a simple family. His father, Andrea Gjadri, a merchant, died when Gjovalini was young, and his mother, Tereze Deda, raised him alone. From 1905 to 1913, Gjadri attended Saverjan College in Shkodër.

In 1914, with an Austrian scholarship, he continued high school in Krema and in 1925; he managed to graduate in civil engineering at the University of Vienna, a degree bearing the protocol number 141. His scientific knowledge of construction engineering was further enhanced. in addition to mastering four foreign languages, such as: German, Italian, Russian and French. After completing his studies in 1925, he returned to Albania, where he was appointed an engineer, at the disposal of the Ministry of World Affairs.

An important moment in his debut as an engineer, from where the consolidation of his figure in the world of engineering would also begin, would be the position of controlling engineer, at Ura e Mati, for the account of the Italian firm ‘Mezzarana’, in 1926 This bridge has been declared a cultural monument.

From 1927 to 1932, he worked as a design engineer at the Bridge Design Institute “Mostovoi Byro”, in the Soviet Union. Due to health complications from the harsh climate, he returns to Tirana. Even on this fact, as we will see below, doubts always arise from the State Security, about Austrian agent activity in the Soviet Union.

With his return, the unstoppable professional work continues, for almost 50 years, with designed works that bear his name. Until the liberation of Albania, engineer Gjadri worked as a design and implementation engineer at the Ministry of World Affairs. After the liberation, he worked in the Ministry of Construction and the State Institute of Design, as a designer and leader in the sector of bridges and statics of construction constructions.

In one of his autobiographies, in the AIDSSH file, in 1945, in addition to the data on his work, Gjadri felt it necessary to show that he was clean as a figure: “During the Italian occupation, I did not write in the Party Fascist, even during the German occupation, I did not cooperate with Germany”

This fact ensures that he will not suffer the fate of those who were convicted as collaborators and continue his work in peace. Of course, all this concern for the purity of his image is related to his doubts about the possible persecution that may hit him, as has happened too many of his colleagues.

Engineer Gjadri, holds the First Class Work Order, obtained by decree of the People’s Assembly no. 28, year 1945, in the agreement it is emphasized: “Although ill, Gjadri threw himself into the construction of all the big bridges without reservations. He worked tirelessly and with the dynamism that the times demanded. He put all his technical skills at the service of the people”.

His scientific and professional achievements are truly impressive. To mention only a part of them, we can say that in the field of projects in the fund of the Central Technical Archive of Construction, projects of over 75 of his engineering works, built in different regions of Albania, are preserved, among which stand out: Ura e Lana (on the big boulevard of Tirana, 1932), Ura e Buna (Shkodër, 1934), Ura e Zaranika (Elbasan, 1934), Ura e Gjanica (city of Fier, 1940), Ura e Mbrostari (Fier, 1945 ), Mezhgoran Bridge (Tepelën, 1947), Rrogozhina Bridge (1948), Bahçalek Bridge (Shkodër, 1949), Mokra Bridge, over Shkumbin (Pogradec, 1951), High water tower for locomotives (Durrës, 1951) , the new bridge of Mifoli over Vjosa (Vlora, 1952), Rubik’s power station (1952), catwalk bridge over Vjosa (Memaliaj, 1953), high Chimney in Rubik, (1954), Bridge over Dunavec (Maliq, 1957 ) and many, many other works, mainly from the transport infrastructure, as well as industrial facilities.

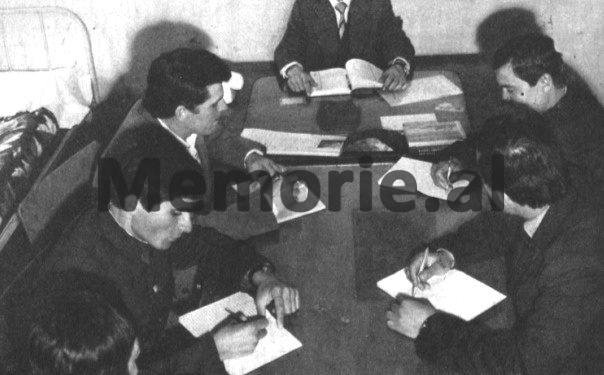

All these achievements make engineer Gjadri rank among the most prominent figures of Albanian science and in 1947, he became a member of the General Assembly of the Institute of Studies, which can be considered as a cornerstone of scientific institutions in the country. 23 intellectuals took part in the Assembly, among them: Sejfulla Malëshova, Spiro Koleka, Aleksandër Xhuvani, Aleks Buda, Petraq Pepo, Eqrem Çabej, Petro Fundo and Gjovalin Gjadri.

Meanwhile, in the field of technical-scientific studies, the following are worth mentioning: Article on the Lana Bridge, published in Bauteknik, 1935; Problems of bridges in Albania, published in the summary materials of the Congress of Berlin, 1936; The Adjezon Problem in Railway Train Motion, published in Bulletin of the Institute of Science, 1949; Three articles on the theory of plasticity, published in the Bulletin of the Institute of Science, 1950; Papers on the calculation of the embedded arch, held in one of the scientific sections, organized in honor of the 20th anniversary of the liberation of the homeland, published by the publications branch of the University of Tirana, 1964.

As far as scientific publications are concerned, the book Science of constructions, volume I, “Resistance of materials”, Tirana, 1965, consisting of 550 pages, has an important weight. Prof. Gjadri had conceived his work “Science of constructions”, in three volumes and in volume II, the theories of earth pressure and vertical beam, instructed in the ground, was treated. It was partially submitted to the university, although without a review, also volume III, on the static analysis of arch-type structures. Completion of the work was made impossible due to his death in 1974.

For the book “Science of constructions”, in 1952, Gjadri wrote a memorandum to the deputy prime minister, engineer Spiro Koleka, where he explains the commitment he undertook to write the book for the Institute of Sciences and emphasizes that, due to his poor health, he needs 3 hours a day of freedom of action, within the official schedule, he also wants to reduce the formal and administrative matters, so that he can finish the book.

What stands out in this letter is his courage to ask for support from the top leaders of the regime for the scientific work: “In my opinion, the issue does not lie in the mechanics of permanence, more or less in the office, but to the academic treatment. In this regard, I have information that, in the Soviet Union, those who are engaged in writing books, only writes books and do not engage in any other work”!

Even a close look at Gjadri’s file reveals a cold relationship with the regime. For Gjadri, the regime is an employer and he does not show any kind of political passion, for or against the regime. For this reason, he will also be accused of “indifference”. So even the dynamics of “collisions”, no matter how small, are almost related to an employer-employee relationship. The regime needs his technical-professional skills; Gjadri needs a job, to provide him with as much income as possible and to recognize his professional merits.

The recognition and evaluations of Gjadri’s work by the scientific authorities of the time prove that the regime was satisfied with his work. No assessment was possible without the consent of the regime authorities. After the publication of the book, there was no shortage of praise for his great work.

In a public review published in the press of the time, in September 1966, commenting; “Engineer Gjadri’s book is written with technical dignity and is characterized by a high theoretical level, both from the point of view of the depth of the argument, as well as from the point of view of the mathematical fabric… The subject treated in it is quite broad and current. .. The book is of great double importance, for engineers and students of engineering…”!

In 1972, in support of the awarding of the title of Professor, there is a review written by docent Andrea Papastefani, where it is worth highlighting his words on Gjadri’s work: “The book ‘Science of constructions’ is the first book in this field of sciences, which is written in the mother tongue. It deserves special attention, for a treatment of the problem of resistance of materials, both from the technical and theoretical side”!

Also, there is a review of his scientific activity by doc. Vasil Pistoli. Among other things, it is emphasized that his authority is also well known by many foreign personalities in the field of construction. As it describes the case of the discussion made between some Albanian engineers, who went to Italy for experience exchange, with Professor Carlo Cesteli Guidi, with international authority who, according to V. Pistoli, had for Gjadri the respect of an outstanding scientific framework.

Gjadri, since 1957, exercised scientific and pedagogical activity at the State University of Tirana, being one of the first cadres in the field of construction, since the creation of the Institute of Sciences. An important moment for Gjadri was the long-awaited and somewhat delayed decision on the awarding of the title of Professor. The scientific council of the faculty of engineering at the meeting of December 6, 1972 decided with 24 votes in favor out of 25 voters to grant him the scientific title of Professor.21

The dynamics of the pursuit of engineer Gjovalin Gjadri

Despite his great work, in the reconstruction of the country, he has been constantly kept under the control of the Security, under the pretext that engineer Gjadri could harm the government. In his file with AIDSSH, the figure of Gjadri is sometimes treated as a clean figure and other times, shadows of suspicion arise. In one of the descriptions of his figure, in a report written in 1949, which begins with the words; “for the categorization of the opposing activity of Gjovalin Gjadri”, there is a clear tendency to cast doubt on his figure.

It is emphasized there: “Gjovalin Gjadri is a privileged man”. The report continues with information on his education in Vienna, his employment in the ministry after returning to Albania, they then mention his employment as an engineer in Moscow, in 1927, and his return in 1932, from the Soviet Union. Regarding the period of work in the Soviet Union, the report continues to cast doubt on the reasons for the return: “During the time he stayed in Moscow and his departure from the Soviet Union, it is not known why, since he completed university in Austria, it is suspected that Austro-German control agent”!

In the first volume of the work of prof. Gjovalin Gjadrit, another engineer in the field of construction constructions, Haxhi Dauti, says: “In the work of the State Security, much was under the sign of suspicion of foreign agency, especially for those who had studied abroad. The problem became more dramatic when, in the pursuit of persons, Sigurimi relied only on suspicions and hypotheses, not on their verification. The observation was carried out in different ways and the spirit of observation was created by the need of power, to have under control any person who could create any problem for him”.

The fact that the government had set up an extraordinary system of control, from the army, the police, the State Security, with a network of spies in every corner of the country, labor control, mass organizations, labor collectives of every enterprise, makes us think that the regime was convinced that it had not created an obedient “new man”, but that everything was a well-thought-out attempt to maintain power through the intimidation of the people.

In the following, the file contains allusions to Gjadri putting his own interest over the general one, a quality that is unacceptable for communist morality. In the following quote, the spy tries to highlight two “negative” qualities of Gjadri: “Putting personal interest above the general one and indifference.

During Zog’s regime, he became a privileged person; he sympathized with the regime and worked for it, until the occupation. He was closely connected with the branch of the sector, where he worked as an engineer. During the occupation, he served fascism in the best way, a man who always looked out for his personal interest and interests, he sympathized with the Italian-German occupation and the traitorous organizations of ‘Balli’ and ‘Legality’, he spoke in their favor, saying popularized them and the National-Liberation war, did not look favorably on it. He did not show any opposing activity as he remained indifferent”. Memorie.al

The next issue follows