By Dr. Ledia Dushku and Doris Pasha

The first part

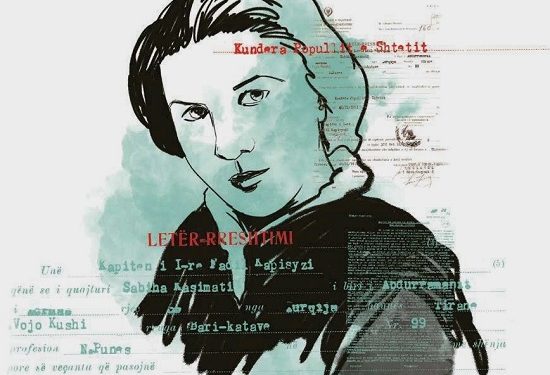

“Communist regime and the researcher”, the case of biologist Sabiha Kasimati

Memorie.al / The article ‘Communist regime and the researcher’: the case of the biologist Sabiha Kasimati, aims to present essential aspects of the activity of Sabiha Kasimati, as an intellectual and researcher, placed in the historical context of the time. The analysis primarily aims to answer the question of who Sabiha Kasimati was and what she represented, before the establishment of the communist regime, in order to further understand the regime’s behavior towards her. The presentation of the character in several perspectives helps the reader to understand to what extent the regime’s behavior towards intellectuals was conditioned by scientific activity, psychological profile features, or the relationship with senior communist leaders, in the case of Sabiha Kasimati with Enver Hoxha himself.

The material is conceived in a chronological approach, while problematic aspects become part of the relevant chronology. The main archival sources used in compiling the profile of Sabiha Kasimati are: documents of the Central Archive of the Republic of Albania, part of the funds of the Ministry of Education, the National Lyceum of Korça, the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies, Party funds (Structures and Bodies Leader), the Prime Minister’s Office; the documents of the file of the investigation of the accused for the bomb in the Soviet Legation and those of the form file, of Eqrem Çabej, consulted at the Authority for Information on the Documents of the former State Security (AIDSSH). Valuable for this paper were the materials of the journal of the Institute of Studies/Institute of Sciences; literature on totalitarianism, on communism in Albania and the placement of the bomb in the Soviet Legation.

The missing State Security documentation for Sabiha Kasimat, there is no doubt that it would have enriched the profile in question. At the same time, a more favorable approach for the legislative researcher to consult the AIDS archive would serve to fully realize what is known in scientific language as indirect research, thanks to which complementary data would be discovered for Kasimatin, from the files of the surveilled characters, part of her social circle. The complete realization of this research would serve to understand more widely and deeply the dark side of the communist regime in relation to the individual/researcher in general and Sabiha Kasimat in particular.

The establishment of the communist regime in Albania and the behavior towards the elite

After the Përmet Congress of May 1944, the path to power for the Communist Party of Albania (KPSH) seemed to be not far off. The resistance against the invaders and after November 1944, the victory over them, gave the communists considerable popularity credits, thus facilitating their rise to power. Despite this, the Albanian communists did not feel very confident in their path, as the only ones towards the legitimization of power.

On October 17, 1945, the Fourth Plenary of the Central Committee of the KPSH took place, which analyzed the internal and external situation of Albania. Enver Hoxha, in his report “On the internal and external situation”, emphasized that; “our reaction (the opposition against the KPSH) was not rooted in water”. According to him, the international situation had encouraged the “reaction”, to organize and create an opposition movement.

He considered as potential opponents, the population of the North of Albania, which was completely under the influence of the tribal leaders; elements dissatisfied with the reforms undertaken by the Provisional Democratic Government; Catholic clergy; “the strata of unexplained intellectuals and who have been or are in the positions of the enemy, or of indifference, the strata of great merchants who have hit the taxes of extraordinary profits, the permanent speculators, the strata of beylers and agallars, who have affected by the law of Agrarian Reform and around these, they can certainly gather in case we do not work correctly and do not properly implement the line of the Front, all those indifferent elements unmixed with politics and who fail to properly understand the maneuver of reaction and our efforts in this difficult situation”.

In such a situation, a harsh and repressive policy was followed against those who were considered rivals by the communists. The establishment of the ‘Special War Crimes Court’, where many opponents were arrested and killed, the war on religious communities, the drastic measures against the rich and the overall intensification of the class struggle, were the policies that the regime decided to pursue. , to secure the power of the communists at all costs.

Meanwhile, the declaration of the internationals in Yalta, to recognize only those authorities “in which all the democratic elements of the population are represented [and] between free elections, they should form governments that respond to the will of the people as soon as possible”, as and the fear of the “southern neighboring enemy”, influenced Enver Hoxha to go to the elections, which he would conduct by controlling every means of information and propaganda.

The researcher Afrim Krasniqi states that: “In the circumstances where the country was, with political opponents forced to emigrate, with critical politicians arrested or exiled, with expropriated owners, with religious communities severely attacked and with a powerful propaganda machine, the regime decided to hold the elections…, sure that even theoretically, there were no more chances for its rejection”.

Elections for the Constitutional Assembly. took place on December 2, 1945 and, unsurprisingly, they were won by the Democratic Front. Through them, Enver Hoxha made the final move that he and the NPSH needed to create international legitimacy and finally take power. The “de jure” seizure of power by the communists and the disappearance of the opposition turned the NPSH into the only political party in Albania. The proclamation of the country as the People’s Republic, the adoption of the Statute of the People’s Republic of Albania, on March 14, 1946 and the recognition that the elections gave to Hoxha’s government, legalized the establishment of the power of the NPSH, although it continued to hide under the shadow of the Democratic Front.

The 10 years that would follow would be the years where the regime would seek to consolidate and as such, would be accompanied by totalitarian propaganda and terror. The construction of the dictatorship state was based on systematic violence, through which many people were massacred, killed and exiled. “Terror,” says the researcher of totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt, “becomes total when, in addition to the opposition, it begins and oppresses society, of which intellectuals is also a part.” The creation of a homogeneous society is one of the main aspects of totalitarianism that, through propaganda, not only tries to influence and change the life of the individual, but also enters the family, its intimacy, destroying every aspect of human individuality.

“As an inseparable part of totalitarian ideology, terror and violence are not subject to the rules of common reason”, – says the other researcher of totalitarianism, Cantall Millon Desol. – “They are carried out through a blindly obedient and well-disciplined police apparatus, which is not only satisfied with the punishment of the accused, but must make him admit his mistakes. There is no other party than the party-state and any objection or opinion against the ideological line of the party is severely punished”. In addition to the thirst for power, terror is also exercised by the tendency to create the “new man”, who must be worthy of the communist society, considered as perfect. In this context, working with the elite was considered an important moment.

For the communist regime in Albania, in its first phase, focusing attention on the process of shaping a new intellectual elite, perceived as such not because of age, but ideological kneading, was considered an important moment. These elite in the near future would help him establish internal peace and ultimately build socialism. In addition to the novice part, which would be educated in the Soviet Union and the countries of the People’s Democracies, the new elite also meant the reformation of the old elite and its education, with the ideas of Marxism-Leninism.

The old elite, educated in the West, with principles and ideologies different from the communist one, that did not agree with the form of the regime that was being established, was considered by Enver Hoxha and the most vocal Albanian communist leaders, as a potential danger.

As such, it had to be “reformed”, to cooperate with the regime, otherwise it was considered dangerous and had to be “eliminated”. The way the communist regime treated the biologist Sabiha Kasimati, represents a model of very harsh behavior of the state towards researchers, in an attempt to eliminate what was considered a political opponent and “enemy of popular power”, with high risk.

Who was Sabiha Kasimati and what did she represent?

Sabiha Kasimati was born in Edirne (today’s Turkey), on September 15, 1912. In 1927, the family settled in Korça. Kasimati came from an intellectual family, where his father, Abdurrahmani, was a well-known doctor at the time. Petro Luarasi, who is one of the few who have studied the figure of Sabiha Kasimati, describes her family circle as follows: “She was born, raised and educated as a pure Albanian in the hearth of a large family in number and value, with wide relatives and deep ties, with patriotic, cultural and scientific contributions…, she died with love for the homeland of her Libohovite ancestors, knowledge and universal values”!

Studying at the National High School of Korça (1928-1931) was an important moment in the shaping of Sabiha Kasimati. It would be the Liceu that, along with the family, would influence not only her professional training, but also the protection of her character. This was not accidental, because the Lyceum had a teaching staff composed of qualified Albanian and French pedagogues, a teaching program where students, in addition to scientific knowledge, received knowledge about moral education as a very important part of human life, followed cultural activities by attended the city’s cinemas, had freedom of thought and were formed as Western citizens.

As a high school student, Sabiha Kasimati stood out for her intelligence, willpower, free-spirited nature and high academic results. But this was one side of her past, related to the Lyceum; the other side had to do with the circle of acquaintances there. There is a possibility that it was at the Lyceum that Kasimati met Enver Hoxha, who studied there. After finishing the Lyceum, Kasimati would be employed at the American School of Kavaja (1932-1933), to return to the Lyceum again on 3 October 1933, already as a teacher in his lower classes. But her stay in Korça lasted only 2 months, as she was forced to resign for health reasons. The Ministry of Education accepted her resignation and transferred her to the “Nana Mbretneşe” Women’s Institute as a French language teacher.

These would be Sabiha Kasimati’s first work experiences, until she started her studies in Italy, in 1936, with a full scholarship from the Albanian state, halved since February 1937. She studied biology at the Faculty of Biological Sciences in Royal University of Turin and graduated in June 1940. The diploma thesis was entitled “Fauna Ittica d’acqua dolce dell Albania” (“Ichthyological fauna of the fresh waters of Albania”).

During her time as a student in Turin, Sabiha Kasimati signed a request addressed to the Albanian Ministry of Education, with which some Albanian students requested to take the exams in the autumn season as well. Given the problems with the Italian language, the difficult subjects and the lack of textbooks, the summer season was considered by them to be insufficient to fully fulfill the school obligations. The signature of the request shows another side of the character of the Kasimats’ daughter, the courage to demand her rights. This makes her, besides smart and intelligent, also a determined person, to raise her voice, to react against what she considered injustice.

After returning from Italy, Sabiha Kasimati, on November 13, 1940, was the winner of the competition announced for the position of assistant secretary, in the personnel of the educational administration. After passing the probationary period, she was appointed assistant secretary in group A (grade XI) of the educational administration staff and on July 24, 1941, she started work. Her status changed quickly, when on November 17, 1941, she became part of the teaching staff of the “Nana e Skanderbeut” Female Normal School (former “Nana Mbretneşe” Institute), as a science, chemistry and hygiene teacher. Health reasons forced him in May 1943 to leave teaching and be hospitalized in Italy. Sabihaja was in poor health and suffered from tuberculosis. She was put “on hold” for a year, until May 1944.

Despite not being an active part in the teaching process, during the “waiting” period, she received a full salary, which was already 200 francs per month, after she had passed to the Xth grade, group A. Non-improvement of the situation health, influenced Kasimati’s waiting to be extended, until May 1, 1945. During this time, she would no longer enjoy a full monthly salary, but half of it. It cannot be left without mentioning the fact that there is a decision, during the time Sabiha Kasimati was in treatment in Italy, which promoted her from a professor of class IV to a professor of class II, group A, with a monthly salary 260 francs.

From the above, we understand that Sabiha Kasimati has been waiting for 2 years and in the first year, she was paid full salary, while in the second year, she rose in rank, without being an active teacher at the “Nana e Skanderbeu” Women’s Institute ” and was paid with half pay. This makes us think that in this period, she enjoyed a privileged status.

Beginnings on the path of science

Sabiha Kasimati’s relations with scientific institutions in Albania began in January 1943. During the time she was working as a teacher at the “Nana e Skanderbeut” Institute, she had a conversation with Ernest Koliq, president of the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies, founded as the Institute of Albanian Studies, in April 1940. Her relationship with Koliq had its beginnings earlier, during the period of schooling in Italy, when, as Kasimati he said: “Your Excellency supported me, as Head of Education that you were “. Immediately after the conversation, she sent a letter/report to the head of the Institute, from which we understand the reason for the meeting.

Sabiha Kasimati presented Ernest Koliq with a genuine scientific project, through which she requested that at the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies, “a zoological collection be formed, starting with the Branch of Ichthyology”, a field for which she had studied in Italy the second year of studies and had defended the topic of the diploma; to prepare “an herbarium after the Albanian flora, as is known, has proven the most lively interest of the most prominent botanists, especially German and European in general”; to collect “in close cooperation with the Directorate of Mines under the Ministry of Economy, the different types of minerals and fossils that are found in the soil layers in Albania”. Memorie.al

The next issue follows