By Nestor Topencharov

Part sixteen

THE DRAMA OF LIFE

(THE STORY OF A FAMILY)

I dedicate this book to: All fellow sufferers. Their families. And in particular, to people who did not have the opportunity to tell the odyssey of life, during the communist dictatorship.

FORE SAYING

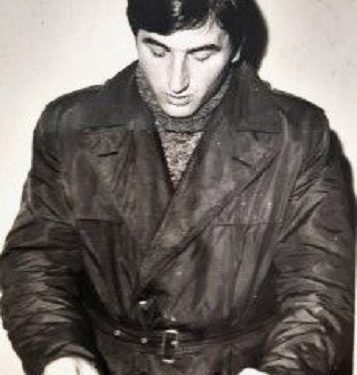

Memorie.al / I were born in the city of Korça, on October 22, 1953. I left Albania in October 1990, after we were given the right to repatriate to Yugoslavia (now North Macedonia) . In June 1992, I immigrated to Italy, where I still live today. Although I have been away for 32 years, I did not cut ties, as Albania was the country of my birth, where I spent 37 years, and that part of my blood is Albanian. Years later, the ties with Albania were strengthened, as I also took my wife from Durrës. We came every year on vacation, but the short time of our stay meant that many contacts were cut off. However, true friends and comrades remained forever in my heart.

In the last three years, I did not have the opportunity to visit Albania. But during 2022, I came several times. My commitment on the one hand and the coincidence on the other, made it possible for me to re-establish connections with friends and colleagues whom I had not seen for decades. Knowing my past, some of them advised me to write down what had happened in my life. At first, this idea seemed like a utopia to me, since even though I had been a good student; I had no inclination towards drafting. Then I reflected. I would just write my story, true events, where not much inspiration was needed. Perhaps a writer would know how to present these events, as a true pen artist knows. While I will write them, without many descriptions: briefly, simply, naked, as they happened.

Something else that pushed me even more to write this book was an interview on TV Klan, which I saw in October of this year, directed by the well-known journalist Blendi Fevziu. I did not seek revenge. But I didn’t even have justice. With the help of this book, I will make known to the Albanian public opinion, the role of the individuals who contributed to my suffering and that of my family. And today, I am putting my finger on these “beings”, not for the task they had, but for the way they performed it. I will start my writing with my grandfather, from my mother’s side, to continue with my father, where I will touch on the most important moments of their lives. This will help the reader to know my background.

Then I will also talk about myself. In this book I will also tell some events, one more dramatic than the other, that happened to people I had the honor of knowing. I am glad that many books have been published on the suffering and persecution of “enemies of the people” and their families in internment camps and prisons during the communist dictatorship. I was able to read some of these works. I believe that this book, in a modest way, will contribute to know even more the inhumane methods of the State Security, the way they created accusations and how they destroyed people and families to keep the people under terror.

Author

December, 2022

Continues from last issue

CHAPTER FOUR

Usually on Mondays, mom would wash her clothes in the tub in the yard. Somewhere around lunch, there is a knock on the door and a person we know appears. He had been in the dungeon with his father for a while and then I had him in Spaç. He was holding a box of hot dogs. He wondered where father was. Sa got the answer, despite her mother trying to stop her, she hurried up the stairs and entered the patient’s room. Mom followed behind and noticed that this person was very worried. After addressing his father, “Koço, Koço”, and as he did not receive any answer, he left the box of Turkish delight and quickly ran away, as he had come. We did not find out why this visit. A few days later everything was clarified.

It was dinner and I was returning home. In those years, the lights of the alleys were turned off and the street was partially lit by the light of a window. When I approached the house, out of the semi-darkness, a friend of mine who lived nearby came out and beckoned me to follow him. After we entered a dark area of the alley, he told me that a few days ago, the Security had blocked off a room, under the pretext that some foreigners were going to pass there, which they had under control. At the end, he told me that he felt guilty towards me, as he had realized that my house would be monitored. His room had served for this purpose. I reassured my friend that he was not at fault and thanked him for his honesty and the great risk he took for this announcement. We said goodbye and parted ways. After that, I made the connection of events.

They sent the doctor to confirm the health condition of the father and the co-sufferer to confirm the doctor’s word. And at the end, the Security check, to see if “their messenger” had appeared in the place and at the time they ordered.

I thought they would leave us alone. But this time it was not like that. When they saw that they couldn’t do anything with their father, they started putting pressure on Ivana. They wanted to use him as their tool, suggesting that he visit the families of Yugoslav immigrants, which they had on their list. They pressured him to serve them. For him, this created situation was very serious.

I felt guilty for letting my sister go to the prosecutor’s office, but now it was too late. This pressure was stopped after a few months. I don’t know if it was Ivana’s strength not to agree to enter this trap, or if the political situation changed. It was important that they left him alone.

During this difficult period for her, my sister tried to keep me out of trouble. These 14 very difficult years that she spent, at a young age, had consequences for her further life. He did not marry. After we went to Yugoslavia, he lived with his parents and after their death, he lives alone. While I, in the last years in Korça, tried to create a family. But my past and the wrong choice made this wish unrealizable.

On the street where I lived, I had a childhood friend, Janin. After leaving prison, often with his sister and his family, we went on excursions outside the city, to the surrounding villages, where churches and waqfes (holy places) used to be. I remember these beautiful moments that I spent in their company. Jani was a very religious man, he worked in a foundry and there secretly made crosses and candles and gave them to believers. In these holy places together with them, we also left pictures of saints, which I made frames with work paper and glass. At that time, many believers had begun to frequent these churches and systematize the fallen walls.

My friend, Jani, also took a family gospel book with him. In the holy place, he read parts of it. His son, Gjergji, a child at the time, stood by his father’s side, which closed the ceremony with a prayer to God:

“To become a priest. If I will not reach him, he will become my son”.

While I was asking:

“Give us the opportunity to go to our father’s country.”

Both of these wishes come true. After the advent of democracy, Jani went to study in Greece. He became the Secretary of the Albanian Orthodox Autocephalous Church. Many years later, I visited him with my wife, in his office in Tirana. This is my friend, Father Jani Trebicka. He retired a few years ago and moved to Boston with his children. Even there, he continues to make his valuable contribution to the Orthodox churches of the Albanian community. We have always been in contact.

In 1989 in Albania, the political situation began to change. Buses with tourists from Greece and the following year, from Yugoslavia, began to arrive in Korça. In addition, the right to repatriation was granted to some families of Greek origin.

From the beginning of the spring of 1990, a cousin of my mother introduced me to a lawyer who worked at the Ministry of Justice. This person, without knowing the past of my family, took it upon himself to help us, to leave the Albanian citizenship and provide us with a passport. We clung to this hope. We had to take advantage of this moment of opening the borders, which were closed in 1956. Another closure would be fatal for us. After a month I met again with the person in question, who had read my father’s conviction files and mine.

He told me that they had punished us in vain and that if he had been the judge in our trials, he would not have punished us. I looked at this high official of justice with surprise, but I did not answer him. In that period, people were still reserved. I thought only that, if he would give us his innocence, the least for him would be a shovel with a long tail. Then this person informed me that he had started our practice.

In the first days of July we met again. He handed me the passports and told me that the relinquishment of citizenship had been approved and was expected to appear in the official gazette. This newspaper came out on July 31, 1990. I thanked this man with all my heart, for the good he did to us. We were in the period when the events of the embassies took place.

In those days, a friend of mine from Spaçi, Musa Hoxha, had entered the Czech embassy. Within a short time, from the Czech Republic, he went to the USA. I heard him on ‘Voice of America’, in an interview he had given. Musai had finished high school in Tirana and then he was not given the right to study, for biographical reasons. He liked literature. We were released in one day. I was glad for this friend who reached that opportunity, since the political situation in Albania was still unclear.

When I showed up at the Yugoslav embassy, there was a crowd of people. With difficulty I managed to get in and hand over my passports and family certificates. After two months, we were given a visa and on October 20, 1990, with a truck with two pieces of loot, we left the territory of Albania, from the Qafë-Thane border point. At the border we had many checks, passing the clone checkpoints first. On the other side, close people were waiting, both from father and mother.

Finally after 40 years, the father returned to his country, to his hometown. Many of the family members were no longer alive. The father in his old age resembled his brother, who had been a few years apart. There were quite a few people greeting him. His mood changed and his health was better. During the period that I lived in Ohrid, we often walked through the streets of the city and by the lake. He lived until March 1999, after receiving the happy news of my marriage with Marinela, the daughter of Dr. Zef Kaçulinit, from Durrës.

When we entered the Yugoslav territory, apart from the family members, there was also a troupe, a cameraman and a cinematographer, who had come for a documentary on a rare occasion. They had been waiting for several hours and at the moment they were about to leave, the case of our father and our family presented itself, which was even more special. After taking all the photos and videos they needed, they stayed in touch with us. Then, two documentaries were made and a few years later, a joint Macedonian-Polish film based on this true event.

In Skopje, I met the Macedonian writer, academician of sciences and arts, Tashko Georgievski, who wrote the screenplay for the movie “Across the Lake”, based on the story I told him. The director we met became the director of this film. His name is Antonio Mitrikeski. For the film’s music, they proposed the famous Romanian composer and flautist, Georghe Zamfir.

At first he refused, but then when he read the script, he changed his mind. In December 1997, in the “Centre” cinema hall in Skopje, the premiere of the film was shown, where we were also invited, honoring us with the presence of the highest Macedonian authorities.

In December of 1990, I became interested in graduating college. After collecting the necessary documents, I registered and took the exams I missed. In November 1991, I received my diploma. Finally, after 15 years, I managed to realize this dream.

As I wrote in the introduction, when Yugoslavia began to destabilize, due to economic problems, I immigrated to Italy in June 1992. I had an uncle in Rome. At first I had difficulties, for a job in the profession. But this period served me to learn the language and get to know the city well. After I needed some documents from my hometown, I came to Korça in April 1994. In Albania, democracy had been introduced for several years.

Those days that I was in the city, I made several visits to the families that we have been friends with. In the first place, I went to a family that shared the troubles. George, he was older than me. He had studied in the Soviet Union and for many years as a naval officer, he had served at the Pashaliman military base. In the city of Vlora, recently, he had met his lifelong friend, Moza. Gjergji wanted to go back to live in Korçë, not only because he missed the city and the company he had, but also because he had his old mother, brother and sisters, with whom he was very close. His request was approved and he was appointed to an important post in the Korça Military Corps.

This did not suit some officers, who intellectually did not compare with Gjergji, and who claimed that place. So to get rid of him, they accused him of agitation and propaganda. When the investigator went to check his apartment, they were reluctant to enter. Moza was also an officer. When she realized the reluctance of the Security men, she went inside and handed them her gun saying:

– “How come you don’t have a hard time! All these men are afraid of a single woman.”

Moza was brave. She was from Tepelena, the granddaughter of the “People’s Hero”, Asim Zeneli. Gjergji was sentenced to 8 years and brought to Spaç. The investigator asked Moza to separate the man. But she agreed to take off her officer’s uniform, roll up her sleeves and work in construction.

During the following years, she remained proud and honored her husband. Her greatest wish was that, when Gjergji was released, she would give him a child. After the release of the husband, the child was not coming. Moza did not leave a doctor or cure undone. One day he told my mother that the Security had ruined his life. During the years she was younger, they had separated her from George.

After we moved to Yugoslavia, Moza, being the fighter that she was, decided to take a risk with a surgical intervention, to make her wish come true. The operation had not been successful. When I met her, she was lying on the bed. George served him day and night. When he saw me, his face lit up.

– “My brother came”, – he told me.

It was heavy. The doctor had advised him that he could only sit in bed for half an hour a day. And this time, he spent to honor me. After a few months, he passed away. This is another family tragedy, a consequence of the dictatorship, which was paid dearly.

In the town near the house where we lived, my mother had a building plot of land, which the neighborhood had donated to an activist, after my father and I were arrested. I went to the municipality to inquire about this property. They welcomed me very well and helped me to get back. I was going down the steps of the town hall. I was with a surveyor friend of mine and another employee of this municipality, when I saw Sami. I stop immediately. I introduce him and greet him, thanking him for what he had done for me.

– “Eh! If only everyone thought so”, was his answer.

I remembered his sad face. I found out later that this employee of the previous administration had been fired. Now that they no longer needed it, many people accused it behind their backs, as a tool of the communist regime.

I feel it as a moral duty to extend this argument. Sami Qazimi, as an employee of the city’s labor office, has helped many people to have a dignified job, and in my case he also took a risk that could cost him his job. People like him had nothing to do with the terror of the dictatorship. Simply, it had been at the service of needy people, at the service of the people.

When I went to the district court and went up the stairs, that outer corridor was packed with people. There I met Dhimitri, the son of a family friend, from the village of Vërnik i Bilishti, Kolo Pandovski. We had been together in the faculty. After I parted from him and turned to enter the court, I see a familiar face in front of me. It was one of my investigators. I was so close that I almost crashed. After staring at her and not sharing her eyes, I grabbed her by the sleeve and asked her:

– “Well, take Ligor Kondili. You don’t know me”?

His answer was:

– “No, I don’t know you”. Memorie.al

The next issue follows