By Rozi Theohari

Memorie.al / Musliu were taken as a soldier at the age of 15 and for 3 years, he did not see his family. When they went to wash clothes in the stream, 16-year-old Musliu secretly cried to his friends, because his father and uncle, two leaders of the National Front, had been shot nearby during the War. At the age of 23, when, after several exclusions and vacations from school and work, he realized that he, the son of the enemy, would never be left alone, he decided to escape to Greece, to then flee to the USA- is. The difficulties of crossing the border in the snow, the concern for the family he had left behind and the great unknown that opened before him, recounted in detail by Musliu himself, as events that memory can never erase.

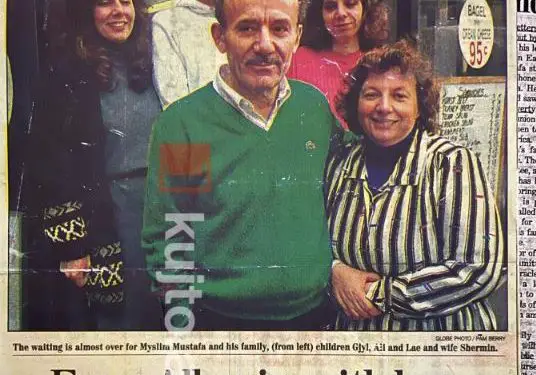

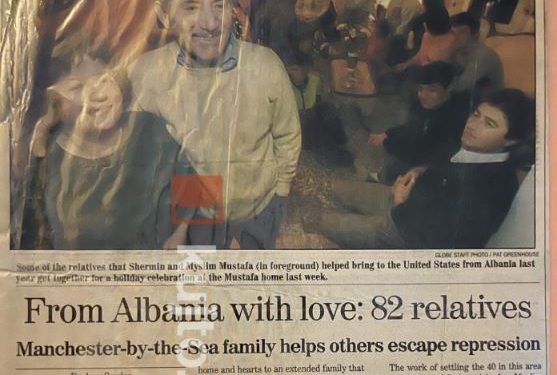

For the life of Mr. Musli, I had heard from Albanian-Americans who knew him, loved him and respected him. In front of me, sitting in his armchair, was a middle-aged man, wearing a thin gray sweater, the color of which went in harmony with his graying hair.

Most of all, attention was drawn to the brightness of his eyes, lively and mobile, and the enlarged palms of his hands, a sign of a constant, tiring and heady physical work that had accompanied the golem or fierak throughout his life. He clasped his thick fingers on his chest and started the conversation first…!

The testimony of Musli Mustafaraj

“I ran away from my homeland, at the age of 23…”, – he began the story with a slightly hoarse, distant and forgotten voice.

“In 1947, at the age of 15, I was called up as a soldier. I was called by the recruitment of Kuçi, in the offices of Fier. Three years without seeing the family. When I finished the army and returned home, they didn’t recognize me, I had grown into a man. While I was trying to find a job, in 1950, I was called up again to join the army. They didn’t even listen when I told them that I had done it once. My grandmother was crying out of despair. In the army I worked in nursing, without documents.

When I finished the army for the second time, I found a job as a nurse in Roskovec. But the shadow of my thirst followed me from behind. As soon as they found out whose son I was, they fired me and transferred me to Patos, where I worked as a normist. They even removed me from there, as soon as they found out about the bad biography. In 1952, I enrolled in the School of Nursing in Vlora. I wanted this profession and dreamed of studying to become a doctor in the future. In class, I was the best in results and discipline. The headmistress of the school assigned me to be the guardian of the class…!

After a month from the start of school, the day came that we would leave for the area hospital, where we would start the practice. I put the class in a row, in the school yard, and we waited for the moment of departure. We were all excited, from this first day. At that moment, the inspector of the Ministry of Health entered the school yard.

‘Are you the class teacher?! Where did we get a boy from? From Fieri’? ‘No, I’m from Golem’? ‘From which family’? “I am the son of Merqe Mustafaraj”. Mouthing the name of the shot father, I had shot myself. The director approached: “Muslim, come to the office.” She could not hold back her tears. The best student in the school was leaving. I lowered my head and clenched my fists.

‘Muslim, I can’t hold you’! – The teacher wrote in oil. I knew, I understood. I was used to these kinds of exceptions. I was calm. I used to get fired. Today from school. I worked hard in the army, since I was a child, 15 years old. I was a soldier, 16 years old, and together with my friends every Sunday, we had to come to wash our clothes in a stream near the ward.

I washed the clothes and cried. My friends asked me; why are you crying’?! I couldn’t tell them that once, nearby, they had shot my father and uncle, as the leader of the “National Front”… In the army, I spent most of my time working. I was a child, but I dug trenches, land with adults. I was on the front line of the border, but I wasn’t running away. I dreamed of studying, so that I could help my mother, grandmother, family…!

When I was expelled from nursing school, I read in the newspaper “Voice of the People” that a course for auto mechanics was opening in Vlora. I went to the Automobile Park of Tirana, submitted the army documents, to give me the right to enroll in school…! I got in the car and went to Vlora, to the pier…!

I finished the course for mechanics, in nine months. The master who taught us the craft was from Himara. He loved me enough, because I was attentive and learned a lot. When I finished the course, I begged him: ‘Send me to Tirana’. He signed the document. I wanted to work as far away from my hometown as possible, to lose track of it.

I worked for three and a half years, in the office of the Automobile Park of Tirana. I had shortened the family name to Mustafa’ for a long time, to escape political persecution…! In 1953, SHNUM (Society for Army and Defense Aid) courses were opened throughout the country, paramilitary courses in aid of the army. First thing in this course, learn the motorcycle. I enrolled in this course and there was no greater joy when I started walking the streets on a motorcycle.

I wanted to buy a wristwatch. I had collected the money bit by bit. Several nights in a row, I stood in long queues, in Mapo e Tirana, but when morning came and the store opened, the watches were sold quickly and, when my turn approached, I was left with nothing. Two winters later, with part of this money saved, I bought an officer’s coat, in the old bazaar of Tirana. Wearing an officer’s coat and riding a motorbike, I now resembled the Security Guards, because at that time, only they used motorbikes.

With an officer’s coat and a motorcycle, I flew to Fier, to my mother and grandmother, to celebrate the New Year. “Don’t go out, brother, what is this that is boasting to us with a motorcycle”?! My biography did the job this time too. I returned to Tirana. There in the office, how they looked at me! I could smell it, that I was going to be fired. Only this time, I didn’t wait for them to let me know. I delivered the engine to SHNUM. Even today, I remember that silent look of pity and acceptance that my friend, who took delivery of the motorcycle, gave me.

I left no debt unwashed. It was early February 1955. I felt cold in my soul and ice in my body. The officer’s coat added to my shivers. I collected the few spoils I had in a wooden suitcase and took them home to an aunt who lived in Tirana. I told him that I would come to pick them up later, when I found a new job. But I didn’t try to find a new job. I met my cousin in Tirana and I told him firmly: ‘I will escape, come with me’? He did not care about this sudden decision of mine.

My mind flew to the family in Fier. We were four brothers and two sisters. We had land near Fier, where they worked. Always dangerous, because it was the time of saboteurs. However, they had nowhere to push them further. The older brother worked as a drilling foreman in the oil wells near Patos. Triskat, they had taken it away from our family in time. In the winter, we had nothing to eat and we waited impatiently until spring came to plant the beans, because they were the first to ripen.

People in my family almost died of intoxication by constantly eating bathe. All this flashed through my mind, while my cousin still hadn’t recovered. ‘Is it coming or not’?! – I insisted. ‘I’m coming,’ he said, ‘but have you thought everything through’? ‘All of them’, I answered and, without wasting time, I went to meet the director of the transport agency in Tirana.

I knew him well, because the Auto Repair Office connected us. I had 2500 ALL in my pocket, I thanked God for not letting me buy that flagged watch. “I want a taxi – ‘Skoda’, to Vlora”, – I told the director, – my mother is sick. I paid 1788 ALL for the taxi. I slept at my aunt’s house, where I had left my suitcase, but I was sleeping. Until three o’clock in the morning, my eye, cup. At 6.00, I left. I took out the cigarette. It was a cold morning, February 28. Sleepless.

I met my cousin at the agency. He didn’t sleep either. We took a taxi and arrived in Vlora before the bus from Gjirokastra arrived. It was a good omen. It gave us hope. When we boarded the bus, there was a little by little. People, standing in front of the bus door, pushed to get in first. Both of us, although we didn’t have tickets cut before, the driver got on us, because it was a rule that office workers had priority in traveling by car. We arrived in Gjirokastra. Without bread and fried.

At “Square of Çerçiz” we entered a restaurant. Without sitting down at the table, the waiter told us that; there was nothing to eat. We insisted. We were hungry. “We have a stale pastiche for days,” he said. “Come here, bring us some brandy.” The pastiche was like a stone. We wrapped it up, took it with us. The brandy seemed to gather our hearts. Not that we were scared. It was an ‘escape’ that we didn’t know how it would end.

We had sworn that, alive, we would not remain in their hands. I had seen when I was in the army, what they did to the fugitives who were caught at the border. We had a cousin who worked at the Sopoti hotel in Gjirokastër. She had her husband on the run. It occurred to us to propose to her as well, to come with us and join her husband. As we said, we did. We went to the hotel, but we didn’t find him, it was a holiday that day.

Her fate, maybe for better, maybe for worse! At 11.00 at night, we started the last journey. The most difficult, without eating, without sleeping, confused, accompanied step by step by the shadow of fate…! After we left the bridge of Korllos, which separates Libohova from Nepravishta, walking and wandering through the bushes, we climbed up the mountain of Libohova. From our hands and faces, trickles of blood flowed. I had done the army in those parts and I knew that at the top of the mountain, there were holes, so we tried to walk to the summit. We reached the snow zone.

We walked sinking into its thick layers, sometimes even getting our feet stuck. Ali was wearing a pair of my shoes, which, being too big for his feet, remained in the snow. He had to walk in socks. Our non-stop journey, from 11.00 at night, until 7.00 in the morning. We were already on the other side of the mountain. The morning sun began to melt the ice that had frozen on our eyelids.

Ali’s legs had turned blood red. I could guess how much pain he was feeling at that moment, but he didn’t give himself away. ‘Hold on, brother,’ I said, ‘just a little…, see that building over there? It is the border post. Wait until we get through that too…’! As soon as we passed the last sign of that great “thing” that we left behind, tied with a peg inextricably entangled with our beings, where the heart of our grandmother, mother, sisters, all of Albania beat, which at that moment it looked like a big steamer submerged in the snow, from which I was moving away more and more, towards the unknown, towards adventure…!

We lay down in the snow and rolled, until we were clothed in white and covered all visible clothing, and just like two snow-white statues, limping, tired and weak, we passed the pyramid, took it down the mountain, panting. and walking without rest and, with impatience. Even today, when I remember that order in my chest, I feel here in my chest, a handful of icy butterflies, which stir and excite my soul.

When we fell from the snow to the stone, we could no longer walk. Below our feet, we could see a Greek village completely burned by the civil war. “Hold on a little”, I said to Ali, but I saw that he could not stand. “Sit here, don’t be afraid, I’ll come and pick you up,” I said and made my way downstairs. I didn’t know Greek. The wretched sight of the village made my condition worse.

I knocked on a large gate, behind which stood half a burnt and deserted house. A scruffy old woman came out, looking at me with some mischievous eyes. ‘Arvanos’, I said half-heartedly. She pushed me to the village chief. As soon as I met the chief, I beckoned him to the mountain where my cousin was. He sent some boys to get him.

Then everything passed quickly and, as if in oblivion. The Greek lit a big fire and placed us a little way from the hearth. He brought us “Metaksa” cognac. My left arm throbbed, while my heart began to beat rapidly. After we recovered a bit, they sent us to Voshtina, the Greek municipality, where the army headquarters was located. The military doctor stripped us of our dirty clothes and wrapped us in woolen blankets. We barely came to our senses. Ali was urgently sent to the hospital in Ioannina.

When he left, my mind remained there, in Ioannina, where, perhaps, his legs were waiting. I passed out profusely, but only for a short time, because, without getting enough breath, I was hurriedly stabbed in Ioannina, in front of the terrible Asphalia, the Greek Security. ‘Kalzoni, why did you come here’?!- screamed the Greek officer, raising his hair up. But I remained calm, even calmer than I could have predicted. I had gone through so many hardships and unexpected things in my life, that… let it be done as it was…?!

But… not to betray my country. When they were convinced that we had no hostile intentions towards Greece, the officer changed the plate. He welcomed me and said: ‘Will you work with us’? When he saw my determination, that even on this side he wouldn’t take a spoonful of water, he got mad, cursed me severely in Greek and ordered: ‘Take this damned thing out’! They took me to the police. Then I was free.

Ali continued to stay in the hospital. His legs saved him. I met some Greek minorities, who had also escaped like us. But they were treated well. When Ali came out of the hospital, we were both taken to the refugee camp in Llavrio, near Athens. There were about 500 people in the camp. There we met many other Albanians. From time to time we approached the borders of Albania and, looking through binoculars across the border, we got tired of the country.

There and the yellow color of the soil seemed a miracle to us. Man becomes bitter because he thinks: ‘What did I do…’! What did my dear family members, relatives, friends think about me?! Were they insulting me or were they giving me the right? What about the grandmother, did she cry for me?! The desert! I knew I would never see him again and tears welled up in my eyes. Late, very late, I found out that one day, when my mother was in the market of Fier, a Security officer had approached her and had spoken to her quickly and in a low voice: ‘Don’t worry about the boy, because he is alive’.

Thank God, they had not moved them from the house, because I was in Tirana and I was called a separate family…! But after ten years, they were exiled from Fieri, to the village of Golem, as a family of kulaks. We spent two months in the Llavrio camp. The UN school was working there, to learn English, because a part of us would go to Australia. America did not take from us.

But I only wanted to go to America, to the country of democracy, where no one would threaten me; that he would fire me or, he would twist his lips with milk, because of my ‘black’ biography. I pleaded with the school authorities and insisted that my wish was to go to the USA alone and that I would wait patiently until that day came. I was given the opportunity to attend a mechanics course for nine months, in Athens.

I lived every hour and minute with dreams. I got a degree. Then I got a visa for America. It was March 1, 1956. Coincidentally, a year earlier, on March 1, 1955, I had set foot on Greek soil. The visa to America, which I still keep as a souvenir today, was a small, square, white form stamped with a thick, black, diagonal line. That black road represented the passage of the Iron Curtain. That visa was only valid for one trip, to cross the Iron Curtain and reach the free world.” Memorie.al

The next issue follows