From Lujeta Progni

Memorie.al / Drane Jakja, is a name unknown to most Albanians. He passed away at the age of 100, a few years ago. I heard about this unusual woman from my mother years ago. My mother and brother lived at the same time as Drane Jakaj, in the infamous Tepelena camp, in the early years of the communist regime. The Tepelena camp is the place where the great drama of communist terror culminates.

Drane Jakja was a Bregdrina girl from the tribal door of Jak Gjon, in Fierze i Puka. Daughter-in-law of Vuksan Prek Ndout, from Nikaj-Mërturi, son of the door of the warrior patriot, Zeqir Dema of Btosha. Drane Jakja, has lived in six regimes.

But the one who would leave a terrible mark on her life was the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. A 100-year journey, covered with suffering, hardship and survival.

She is the grandmother of the well-known popular singer Gëzim Nika. She has managed to hold in her lap, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the fifth generation. But the tragic fate of her 2-year-old son would never be erased from her mind for life.

She lost a 2-year-old son in the internment camp in Tepelena. The story is unusual, terribly painful. It’s one of those stories that take your breath away when you hear them.

Doruntina of modern times, Pjetër Meta, the author of several texts that talk about the history of Nikaj-Mërtur, has called him. Drane Jakja is a symbol of superhuman endurance. She is the woman who defied fate.

Pjeter Meta presents in detail the very dramatic story of this unusual woman. A summary of this story follows below.

How did he exhume the 2-year-old boy, to take him with him after exile?!

At the end of November 1948, when the iron curtain of the East fell like a stone between two eyes, between London Albania and Kosovo, Drane Jakja said goodbye forever to her renegade husband, Vuksan, who returned the rifle to communism, since when enter in November 1944 in the Kolçi Pass, to kill the sons of Nikaj-Mërtur.

Drandja promised Vuksan that he raised his sons and fathered them as husbands in his trolly and escorted his daughters-in-law to good homes. At that time, the youngest of their four children, Zefi, was only ten days old.

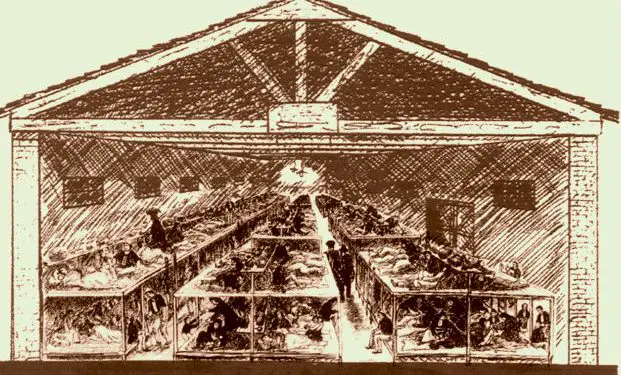

In 1949, without even knowing it, the police and the State Security moved Drane Jake with four children, to the ordeal of seven deportations: three places of residence in the Nikaj-Mërturi region, in Tropoja, for six weeks and, from here, on foot with a cradle on his back, used as a child, to Kukës and, from there, by car to the Castle of Berat, where they stayed for three months. In the end, in the two famous camps, in Turan and Tepelena.

In the inhumane camp of Turan, with several tragedies a day, where 33 children lost their lives within 24 hours, her little son, two-year-old Zef, also died.

Drane Jakja, with great difficulty, built a safe grave with depth and boards, at the cemetery of the Italian soldiers of the war, because he did not want to happen to him like some other internees, who were taken by the erosion of the mountain, or the waters of the Vjosa, the remains of their innocent dead

The time is coming when the internment was forgiven to a large part of the innocent, as the camps were overflowing with interns. This is because 49 trucks with internees from Mirdita alone arrived in Tepelena, after the murder of Bardhok Biba.

When she received the news that she would return to her country, Drane Jakja, together with the great lady Zoje, left the camp of Tepelena, to that of Turani, to the grave of Zefi.

Drandja Jakja dug with circumstantial means and, her bloody fingers, took out the buried boy three months ago. He wrapped the boy’s face clean, with a white sheet, and returned to the camp.

But the tragedy continued…!

Grandmother Drane Jakja kept her son in the Tepelena camp for seven weeks, under the care of the chief and hygiene, to save the face of the son and herself. When he saw that no one could escort him to the distant Tropoja, he went and got his leave and, in a special car loaded with cotton, he left Tepelena for Shkodër.

There he goes from the market, where he once bought the wedding clothes and with his own savings, he bought clothes and underwear for the dead son, who had left him in the hotel, with the other children, waiting for the arrival of their uncle. Not even in his dreams, Zefi, now pale and white, had never thought of dressing so beautifully.

The real Doruntina, Drane Jakja, just like in the legends, after crossing seven big rivers, from Vjosa to Drini, after crossing seven mountain ranges, from Tepelena to Nikaj-Mërtur, after seven days’ journey, by car and on foot, from the internment camp in Fierza and, in Btoshë, he buried the two-year-old little Zefi, next to his grandfather, Prekë Ndout, in the troll of Zeqir Dema, in his native village.

From both sides of the Drin, from Malësia e Gjakova and Malësia e Madhe, came to this funeral reburial of the unseen and the unsuspecting, with traditional honors at the head, this escort of the unseen.

The Burrnesha of the Albanian mountains, Drane Jakja, made her bequest to her husband and, unlike the ancient Doruntina of the Illyrian-Albanian myths, remained alive. Great-grandmother Drane Jakja, started her life seven times over: three times during the exiles in Nikaj-Mërtur, once in Tropoja, the then capital of the district, in the fortress of Berat, in Turan and in Tepelena.

Her last settlement, when she started all over again, is Bukova in today’s municipality of Llugaj in the Gjakova Highland Valley, where she opened new land for land and bread, erected the tower and built her life on a half century.

This was the brief history of this unusual highlander. She closed her eyes a few days ago and took with her the great joys and pains of this life. This story, along with the stories of all those mothers who lost their children in Tepelena, is a great tribute to this society that has deliberately buried the communist past.

The generations must know the history whatever it is. No one can hide it, because they are stories that will be told from generation to generation. History is not undone.

It is not the reparations in money, (which the governments after the 90s promised and continue to promise), washing with the history of the past. In respect of the inhuman stories that a large part of the population went through under the communist regime, the story must be told as it is. Leave the files, because they are never opened. They have no way to open up, because the political elite has its roots in that system.

This 25-year-old proved this. But space is needed to tell the story, as it were. It is not possible for the Albanian media to continue to bring the rosy stories of the communist leaders and to erase as if they had never existed, these tragic stories that these mothers, these Albanians, went through.

It is known that; “a history that is forgotten is destined to repeat itself”. And if it is not repeated in those forms as under the bloody communist regime, in other ways they have repeated history in these 25 years.

Those who were persecuted in the communist regime, in some way, continue to be so even today. Those who were privileged under that regime are today the political elite of the country. And this elite, goes beyond any imagination, decorates the communist persecutors. Memorie.al