By Rudina Lazari

Memorie.al / “Ah, if only one of the Marubs had been alive”. This is what he is said to have said at the beginning of the 90s, the Shkodran riding on top of Stalin’s bust, while tying the noose around his neck. Unfortunately, in those moments, the entire Marubi dynasty was buried, but they had left a large footprint of 150,000 negatives, which constitute the most golden fund in the history of Albanian photography. All the moments of history since 1858, when Pjetër Marubi shot his camera for the first time in Albania, until 1944. The major Albanian figures, all Albanian costumes and natural landscapes, are sitting cross-legged, in what is called a photographic masterpiece of Marubi dynasty.

This art in Albania and not only here but in general in the Balkans, then brought out the great masters, but the first beginning precisely in the Marubes, who had the special merit of fixing on celluloid and appreciating the figures of the Albanians and their history. In the real photo-encyclopedia of the Albanian world, in the span of a century, they decide what to do. Perhaps this seems to be the true historical mission of the 150,000 negatives of three generations of Marubi, which are fanatically preserved in the “Marubi” Photo Gallery. And throughout this encyclopedia, you can naturally encounter the diversity of the Albanian universe. Historical, ethnological, folklore, architecture, urban planning events, without leaving aside a whole gallery of costumes.

The famous dynasty

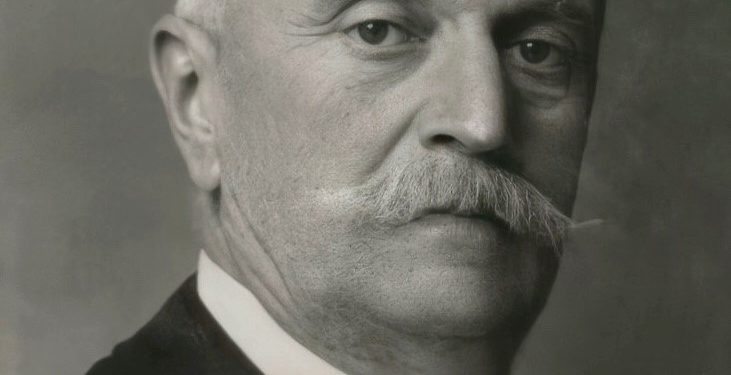

It is not one or two, but there are four, those who formed perhaps the first Albanian artistic dynasty of photographers. Three generations, a century. Pjetri, Matia, Keli, until the last one, Gega. All of them had only one goal: to photograph, and to photograph artistically, everything in front of them. The story starts with Pietro. According to a study by Ismail Kadare, which refers to historical facts, Pietro Marubi, born in Piacenza, Italy in 1834, had to flee his hometown for political reasons. Political ideas, Garibaldist activity and participation in the fight against the Austro-Hungarian occupier of the time, were, according to Kadare, the main reasons that pushed Pietro Marubi to flee his hometown.

In addition, around the year 1850, he sought to settle in Shkodër, trying to secure political asylum, near the Ottoman government of the time. Architect, sculptor, painter, Pietro first saw the art of

photography as a hobby, and then it would become his profession, thus opening the first photographic studio in Albania and the Balkans, in 1858. “His favorite city , will welcome with open arms the magician of the time, who ignited some powders and liquids and then gave you a piece of thick paper in your hand, where exactly you were”. More or less it was said in the chronicles of the time.

It is not known why the first of the Marubi chose Shkodra. On the one hand, the city was an integral part of the Ottoman Empire and, therefore, according to the ideas of the official religion of the time, the configuration of human beings, which is strictly taboo. But, on the other hand, the Albanian city in the north of the country, near the high mountains, was first an epic province, where epics and songs of the legendary Kreshniks were sung. In such an environment, Pietro Marubi, after several years of staying in Shkodër, calls himself; “Peter Marubi, Shkodran among Shkodrans”. So he takes the first picture.

The precise date is not yet known!

Only the year is known. 1858, more or less 24 years old, Pjetri puts the magic apparatus in front of the 79-year-old Shkodran fighter, Hamza Kazazi. The latter poses dressed in a party costume, with a frock and a long sword and two jatagan pistols hanging from his hip. This is said to be the first contact of the master photographer, Marubi, with the Albanian world and which will be followed by several others. The word takes the data; “An Italian has come to Shkodër and works miracles”. People looked at him with fear at first and then everything comes naturally. This is how the first workshop was created, which Marubi himself called “Driteshkronja”

According to the data and testimonies of the time, it is learned that the atelier is something between reality and mythical, at least that’s how it was considered at that time. A large room with an area of 35 square meters, half of wall, half of glass. The right side of the walls and the roof were all made of glass, in order for the light to enter and penetrate naturally. The first black and white clichés were of the 21 x 27, 26 x 31 and 30 x 40 formats. Then they came and changed and the photographer managed to make clichés of almost all the formats of the time. Let’s not forget that we are in a time when Europe, only a few years ago, knew the wonderful art of photography. As for the Marubi, the reputation in a few years is growing. Not only the reputation, but also the name. Various world bodies, magazines and newspapers conclude contracts. It is no coincidence that the photographs of Pietro Marubi’s time are found in many Italian and French newspapers of the time.

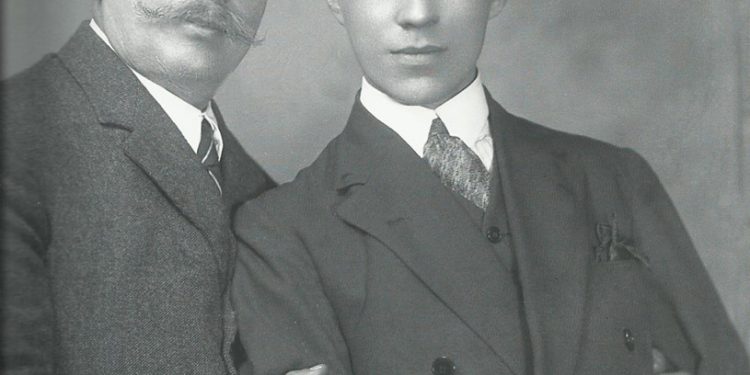

Pietro Marubi, having all this work gets the first aid. A boy from the mountains somewhere around Shkodra, the son of the gardener of his house, Mati Kodhelin. Born in 1862, Matia is amazed by the work of the master Marubi, so in this regard, he asks to be employed by the master. This sends him to Trieste for a specialization for a while. Then he returns to Shkodër, to work with Pjetër Marubi, but unfortunately life for Mati Kodheli is very frugal. Only 21 years old, Mati Kodheli closed his eyes in 1881, but still leaving a significant name, in what will be called; “Dynasty of Marubi”.

His place is not left empty. The passion does not go outside the Kodheli family. His deputy is Kel Kodheli, one of Matia’s brothers, who, after specializing for some time in Trieste, works with master Marubi. It is precisely at this time that Pjetri modernizes his studio according to European standards. Thus, the studio will have two names; Pjetër Marubi and Kel Kodhelin, who works with the same passion as his master. The works of Kel Kodheli begin to have the same success.

Thus, Peter prepares the will. For Kel Kodheli, study e, even the last name. After the death of Peter Marubi, the dynasty will have other heirs, surnamed Marubi. Now, the proper name is Kel Marubi. For this work, it is in particular an art and photography takes a different direction. Every social class has the right to be photographed. This will be the motto of Kel Marubi’s work. At least that’s how it appears from that part of the photo library, which bears the seal of Kel Marubi. The common people of the people, all alongside the upper classes. The huts next to the salons, the clergy next to the huts, history, landscapes, costumes, were photographed again and again.

His fame soon crossed the Albanian borders. In Montenegro, they call him from time to time, and Kel Marubi is among the first photographers to photograph the enemy of the Albanians, Kral Nikola. His passion will also be transmitted to his son. Gega will thus be the last of the centuries-old dynasty, its third generation. In the 20th years of the 20th century, he attended a professional course with the La Lumier brothers in Paris and Lyon, for photography and cinema. The first falls in the Balkans, in the center of Shkodra, the cinema. The first one projects the film, which was called in a hall of Shkodra, its cinema, there around 1914. This is what the people of Shkodra started to call this with jokes, irony or fear; “dream in meringue”.

In the 1920s and 1930s, along with photography, cinema became Gegë’s second passion and Shkodra would be the city of film and cinemas. (A time paradox in the new millennium; Shkodra has no cinema!). In the 1970s, Gega would be the first to give color to Albanian photography. According to what Tereza Marubi, Gega’s daughter, tells us, in 1972, with a personal letter from the First Secretary of the Central Committee of PPS, Enver Hoxha, Gega handed over the archive of all the Marubis to the state. “It was something that my father did with pain,” says Tereza. The toil and sweat of his ancestors, private property, changes hands. It passes into the hands of the state, the property of everyone and no one. Thus, the 150,000 negatives that form the photographic encyclopedia are named in his honor; “Marubi Photo Library”.

The silver bromide plates of this photo gallery have captured different looks and faces, from kings to ordinary people, from legendary heroes and heroes of books, to simple post office or village clerks. Villagers waiting in line to see the doctor, artisans working in the old town bazaar. One by one they all come and sit quietly, in front of the cameras of the Marubi dynasty. And the dynasty of the Marubi, thus gives life to the dynasty of the arts of photography.

Appreciated and underappreciated as the case may be, the art of the Marubi is and remains unique in Albania. An object of illustration for historians, folklorists, ethnographers, architects and urban planners, he receives more praise from foreigners than from Albanians, although the art and the object of the photographs are deeply Albanian. One album in France, one in Italy, half in Albania. In addition, a small leaflet given only to foreigners, published about 12 years ago. Everything will be summarized here. Albanians, apart from the fact that they were photographers, know very little about the Marubi. Foreigners can enlighten us more. Currently, in Montenegro, a photo-exhibition is being prepared to open with the works of the Marubi, for and in this country. In Cetina, his photos were among the most expensive.

“Bar-Cafe-Krajlin” in the center of Cetina, there were no paintings or decorations on the walls, while these were filled with large-sized photos, taken from Marubi’s negatives. In Italy, in 1998 in Bari, an exhibition is organized. In the spring of 2000, another exhibition opens in Rimini. According to Teresa, Gega’s daughter; “I felt proud of the last name that I bear more than anywhere else in Bari, in an exhibition opened by the municipality of Bari, the deputy mayor of the Municipality, the lawyer of the Municipality and a member of the Marubi family were invited. All were arranged by the municipality of Bari Even visa and travel expenses”.

“The exhibition, – says Tereza, – was a complete success. – Many visitors looked in wonder at the photos of the last century. How today I remember the words of the culture assessor of the municipality of Bari. With an exaltation that cannot be expressed , he was trying to explain to the people. Look at the two plans of the photos, the combination of light and shadow, are at the highest level. He stopped in front of a picture of Ded Gjo Luli’s fighters and showed only the human plan, the faces and portraits of the fighters and the second plan, the environments, the mountains which were realized and reflected with a great artistic force”.

Besides being photographers, the Marubs were also Albanian artists. The others who appreciate them are again the foreigners. A French association, “Eredite Sans Frontiere” (“Heritage without Borders”) extremely revalues Marubi’s photographs. The only activity in Albania is organized precisely by this association, while from time to time, someone remembers to organize an Albanian photography contest. While on the other hand, the photo library is an institution left almost in oblivion, while for two years, there is talk about its institutionalization. This means that the photo library will be transformed into the National Institute of Photography, dependent directly on the Ministry of Culture, without having to work with the local government bodies of Shkodra, which raise their hands when it comes to any funding. Of course this can change things for the better.

At the end of the day, the photo library will have a better appreciation of the Albanians and a large number of funds. Perhaps this would also help with copyright enforcement. “For 6 years, – explains Tereza Marubi – we have had trials after trials. Finally, it has been decided that we should be recognized as copyright holders, as members of the family in a straight line. So far, no derivative of this, although we should have had many material benefits”.

In other words, the existing Marubs, those who currently live in Shkodër, have no rights over the photo library (although until recently they were its sole owners). The Museum of Shkodra had to give the family, according to the law, precisely the copyright. In the museum directorate, they say that we need a letter from the Ministry of Culture, while such a letter has never arrived. “I’m already tired,” says Tereza. “I would like to at least appreciate the Marubes, for their merits. Nothing more.”

Parade of costumes and characters

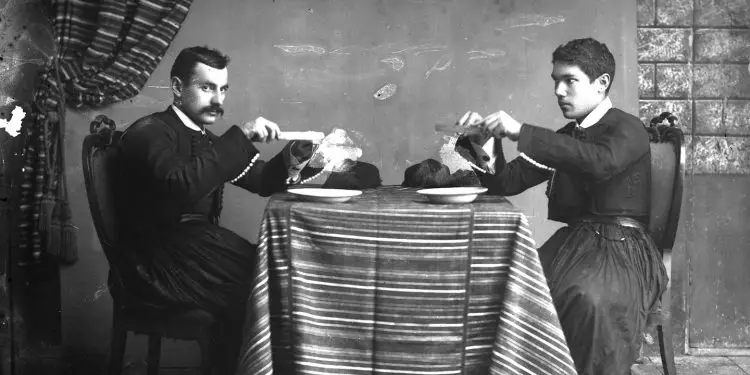

Being Italian, so not Albanian, one of the first things that catches the eye of the head of the Marubi family, Pietro, is of course the costumes. The combination of colors, the masterwork, the fixed cut, their variety, make it marvel in front of the people who wear these suits. Among the first things, even when they are historical, to be photographed are precisely the costumes.

Thus, apart from the masterful side in the combination of light and shadow, in the placement and penetration of the way of light as much as it should, in the clear extraction of the human figure and portrait, where you can also distinguish the characteristics of the people, in the artistic realization of the second plan of background, Marubi seeks to highlight the costumes as well. Very soon he begins to distinguish them. Learns the division according to regions, sexes, age groups, social categories and situational cases of their clothing. According to ethnologist Agim Bido, Pjetër Marubi sought to fix the social and historical poly-functioning of traditional costumes in Albanian life, but in his own way, giving them the value of temporary historical documents of the era in which they were presented.

Coincidence, coincidence or intention, but the first Albanian photo, which bears the seal of Pjetër Marubi, the one that shows Hamza Kazazi, is exactly the photo that also shows the traditional costume of Albanian men from Shkodra, on a holiday. This is how it happens in most cases, most of the photos show costumes of different types. In general, the characters, or the groups of characters in the Marubi’s photography, are dressed in national costumes, they present their images, as they are in parties, ceremonies, family settings, even in the exercise of their artisanal crafts, in Shkodra’s bazaar .

Such a passion is inherited by the entire dynasty. Matia, Keli and Gega. In different ways, they began to give the costumes, thus also giving the time evolution of the Albanian costume design. Seen like this, the “Marubi” Photo Gallery can very well be transformed into an ethnographic museum. Thus it is easy to determine the starting time, from the clothing of the persons photographed. The first pictures have characters in frocks, typical of men’s clothing, of the middle of the 19th century. Then, their place will be taken by the tirqas, which were used at the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, these were replaced by panties.

The same goes for women’s clothing. The dress of the highlanders, the dress of the Mirdita princess, the dress of the Catholic woman from Shkodra, or the Muslim woman, are best reflected in photographs. Behind these costumes, the biggest figures of the history of the Albanian North are naturally seen. Patriots in groups, from Lezha, Dukagjin, Mirdita, Kosovo, all dressed in costumes. The heads, the familiar names on the celluloids of the Marubs, will remain even more familiar and will become well-known in portraits as well. Ded Gjo Luli, Mehmet Shpendi, Azem e Shote Galica, Esat Toptani, Filip Shiroka, Haki Stermilli, Hil Mosi, Fan Noli, all of them were photographed except by the Marubi.

The last of the Marubi

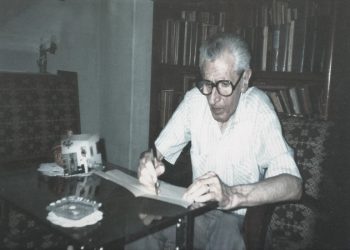

Having lived until recently, in 1984, it is understood that in Shkodër the most vivid memories and the greatest respect, people keep for Geg Marubi, the end of the dynasty of artistic photographers. “Mr. Gega, you were a great man”, say the people of Shkodra, always attributing to him the epithet of “master” even when you should have been just a “friend”. “I remember order and discipline from him,” says Muhamet Bushati, a photographer who worked with him all his life.

“He came to work at a quarter to seven, he had everything ready, solutions, negatives, cameras, so that he could start work at seven. He had a calligraphy to be envied. He kept everything very tidy”, remembers Bushati. “When I was little”, – says Tereza, – “I remember the room at the end of the corridor, where I was strictly forbidden to enter. I could see from afar, it was the archive from which the photo library came. Everything was in order, perfect” !

In addition, Tereza also remembers the big register; “It was a big book, where the dates and the people or families photographed were accurately marked. It so happened that after 5, 10, 15, or 20 years, different people asked my father for a photo of themselves or their family. ‘Mr. Geg’, I need this photo, of Krajave or Bushatllinje’, the word comes.

“At least a year is enough for me,” said the father, and everything was found in a few seconds. Then the tabs were opened and the negative was immediately found in the archive. I loved to see my father at work. I asked him with curiosity, about the red lights, why this or that solution was used, how long the printing takes, and he patiently answered me about the smallest details”.

Epilogue

It is said that the Marubi dynasty ends with Gega. In fact, after his death, none of the Marubets inherited the profession, they no longer had the camera as an indicator of his art or his soul. Meanwhile, from the Marubs, from their school in Shkodër, a whole generation of photographers is created, who in one way or another, create their own dynasties. The Jakova, the Pistulli, the Nënshati, are all those who start to give new names to Albanian photography. While the only daughter of Geg Marubi, took another direction. Photography is just a pleasure for him. He enjoys seeing it, knows how to appreciate it as few people in Shkodra can. As a profession, it is not for him.

But it seems that the genius of the photographic artist has been transmitted in oblique lines. “My son, Tani,” says Tereza Marubi, spontaneously, “he has obvious inherited tendencies. I see this in the way he takes photographs. The light and shadows are perfect. The photos come out clear, clean and taken in all directions”.

Now there is a profession, which is far from that of being a photographer. For the dentist Irtan Mëhilli, maybe the day will be near when he can open an exhibition, thus starting the fourth generation of the Marubi dynasty, the fifth generation of famous photographers, who made a big name, not only in Shkodër and Albania , but also further. Memorie.al