From Alma Liço

– “A neo-communist, a member of our left-wing government, some time ago, called on the victims of the communist dictatorship to apologize to the executioners”! –

Memorie.al / – … Unbelievable: A few days ago, a member of the current government, a neo-communist, with cynicism and shamelessness, asked the victims of the communist dictatorship to apologize to their executioners, for the attitude that some figures of Albanian nationalism during the second world war, (such as Mit’hat Frashëri, Mustafa Kruja, etc.), who, according to him, had collaborated with fascism and Nazism to the detriment of national interests. And for this it refers to the history written and manipulated by historians who came out of the laboratories of communism, a period still not treated objectively and impartially.

As I was reading the book “Sunflower” by Simon Wiesenthal, I felt an inner impulse to react and give my opinion on the possibilities and limits of forgiveness, discussed so extensively in this episode of the author’s life.

The story of the terrible suffering in the Nazi concentration camps brought alive for me the terror and genocide against the Jews during that ugly period of human history. The event experienced by the author is written quite beautifully and with originality, with a simple, fluent and understandable language. Simon Wiesenthal is one of the few survivors of that camp. We have read hundreds of such stories.

But what make this painful narrative special are the report and the dilemma that the author shows regarding the forgiveness requested from him by a criminal, an SS officer, who was passing away, in those environments where terror and death prevailed. . Amid wounds and bandages that oozed blood and pus, the twenty-something SS had witnessed his terrible crimes and, deeply repentant, had asked the imprisoned Jew to forgive him.

Under the weight of terror and mass extermination, the author was obliged to listen to the dying young man’s confession to the end, and then he quietly left, silently refusing to take a stand on his plea.

A few hours later, the SS officer had closed his eyes. This event was engraved in Simon’s consciousness and many years later, he asked the readers of this episode how they would have acted in the same circumstances. Naturally, the ambiguity of the author, and to some extent the clouding of conscience, has sparked quite different opinions, published together with this book.

In her opinion, regarding the possibility and limits of forgiveness, Mary Gordon, professor of English at “Barnard” College, author of four bestselling novels, writes, among other things: “Forgiveness close to mind can be good for both parties, but oblivion can never be good; firstly because it is a form of denial, and secondly because only the acknowledgment of guilt by both parties can begin to prevent the repetition of heinous acts. By securely branding the sinner, public rituals of penance ensure that the deed is not forgotten.”

While Hans Habe, editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Die neue Zeitung”, in Munich after World War II, wrote: “Forgiveness is a spiritual matter, punishment is a legal matter…! Amnesty granted to a murderer who goes unpunished is a form of complicity in crime. It does not encourage forgiveness, it excludes it…I cannot accept the excuse that the system absolves the individual from responsibility…! To forgive without justice is a weakness of complacency.”

Cinthya Ozick, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, winner of several awards for novels and short stories, writes: “We are often asked to reason in this way. Revenge brutalizes, forgiveness ennobles. But the opposite can also be true. The rabbis said: Whoever shows mercy to a cruel person will end up indifferent to the innocent.

Even forgiveness can brutalize…forgiveness is merciless, it forgets the victim. It denies the victim the right to his life. It extinguishes suffering and death. It drowns out the past. It cultivates sensitivity to the killer and insensitivity to the victim…! Forgiveness is relentless. The face of forgiveness is soft, but very harsh for the victim.

And yet, this episode of Wiesenthal’s life did not stop him from fighting for the punishment of the Nazi crime. The documentation center he created, which tracks Nazi criminals, has helped bring 1,100 people to justice since the end of World War II, a contribution for which he has been honored by the governments of several countries, such as the US, Netherlands, Italy, Israel.

…Without pretending to list myself among the prominent and experienced figures who, based on the author’s dilemma, have given their opinions about the possibility of forgiveness, I cannot but express my position on the inhumane, unwavering relationship of the communist criminals with the victims theirs, experienced by hundreds of thousands of Albanians.

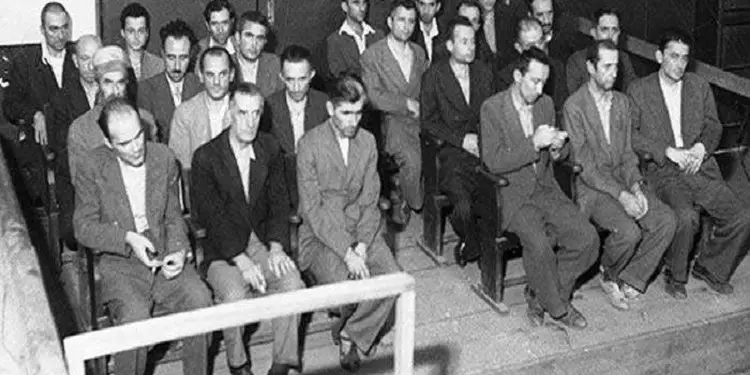

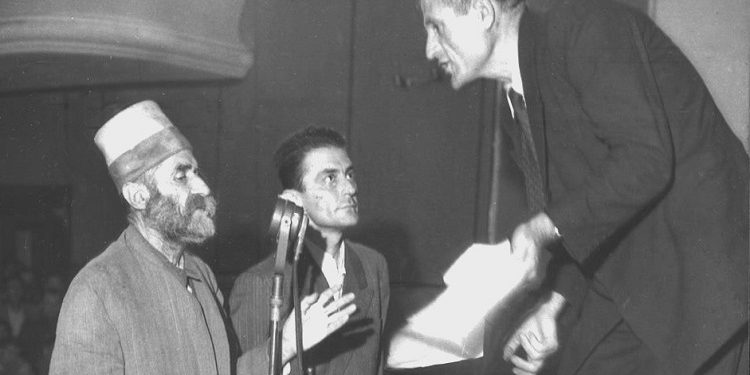

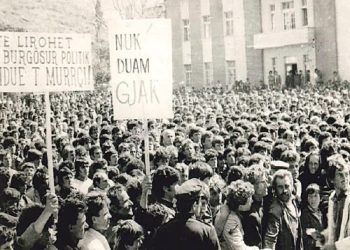

Generation after generation, innocent victims have experienced, and still experience, the barbarity of those who not only do not show the slightest signs of repentance, for their crimes of fifty or ten years, but on the contrary, continue that criminal war, with the same diligence Of course, with the new forms made possible by time… dismissal from workplaces, throwing on the highway, mockery of the right to be compensated for the criminal and abusive punishments suffered, unworthy parades in endless judicial processes, in desperate search of violated rights…re-looting property seized by their fathers,…etc.

In my estimation, repentance is a long process of a conscience of the individual, who has sinned or committed crimes, which must be followed by his efforts to somehow repay the damage caused. Therefore, I share the same opinion with some of the personalities who have expressed their views that an apology cannot and should not be requested.

It can be given by the victim, if he really feels that the sinner’s repentance is sincere and that he, the sinner, has given all his soul and energy to minimize the damage caused. So, in my opinion, apology is not required, it is deserved. This step, not easy, serves to reconcile the wounded souls of the victims, as well as a much-desired social peace.

But my opinion has nothing to do with the reality of the crime-victim ratio in Albania. To our bitter fate, the communists, and especially ours, remain the most ruthless criminals in the history of communism in Eastern European countries, who massacred their fellow citizen’s generation after generation. There is no way they will repent, much less apologise.

There is a complete lack of state and legal will to punish them according to laws and international law. The people involved in communist crime who managed to show some kind of remorse and remorse for their victims can be counted on the fingers of one hand, and unfortunately, their remorse came after them, too, at some point certain lives, contributions and coexistence with the terror of communist ideology, have experienced the cruel crime and punishment of war within the species.

They were condemned by those whom they had trusted, and supported in the direction of the bloody power, emerging from the fratricidal war, as well as the collaboration with Albania’s most vicious and atavistic enemies, the Russo-Yugoslavs

Even in our little Albania, the unimaginable still happens. The incredible. Some time ago, a member of the current government, a neo-communist, with cynicism and shamelessness, asked the victims of the communist dictatorship to apologize to their executioners, for the attitude that some figures of Albanian nationalism have taken during the Second War World, (such as Mit’hat Frashëri, Mustafa Kruja, etc.), who, according to him, had collaborated with fascism and Nazism, to the detriment of national interests.

And for this it refers to the history written and manipulated by historians who came out of the laboratories of communism, a period still not treated objectively and impartially.

Although in the opinions and attitudes towards the dilemma of Simon Wiesenthal, I became familiar with crimes of the most diverse, (such as the Holocaust, Apartheid, etc.), nowhere did I come across the absurdity of the request that the executioners address to the victims, according to which they, the victims, they should apologize to their criminals and torturers, for five to ten years?!

I read about the “Theory of Helplessness”, developed by a scientist named Martin Seligman, according to which nothing can be done to control or improve a certain condition, by people who have suffered and suffered the consequences of her, for a relatively long period. Desperately, I feel like a tired victim of it.

It is with pain and sadness that I conclude that although repentance and forgiveness are amazing processes of resurrection, we, the victims of communism, will never be able to experience them. No, in Albania still dominated by the legacy and communist barbarism. Memorie.al