By Reshat Kripa

Second part

Memorie.al / “Sometimes, when difficult trials fall on a child’s head from the earliest age in the secret recesses of his soul, a kind of scale is born, a precious scale, with which he weighs the affairs of this world . Feeling himself innocent, he submitted to his fate without making a sound. I didn’t cry at all. He, who has no reason to be scolded, does not scold others”!

(Viktor Hugo, “The Man Who Laughs”)

SHORTED YOUTH

Dedicated to family and society,

Author

After two months. We were at school. A loud roar of engines and the sound of an alarm siren echoed through the city. A squadron of Allied aircraft began bombing the airfield. The teachers gathered us all, on the ground floor of the school. We were quite close to the airfield. The roar of the bombs was terrible. There was a great panic.

Some of the children of the first grade started crying out of fear.

– “Don’t cry baby? There is nothing. A little more and they will leave.”

The teachers tried to calm the students down. Finally, the bombing stopped. You could hear the planes leaving. Their noise came and went, until it died away. It was the first time we experienced such a bombardment

At this time we see the mother coming in alarm. He only calmed down when he saw that the three of us were fine. He took us with him. Several destroyed houses could be seen on the road. It was said that near the airfield, several people had been killed. Further on, I saw a dead horse. It was not known why such a thing happened, because of the pilots’ error, or if it was done on purpose.

This event showed me that the “Kavaja Street” area was not a safe area. It was near the airfield and as such, could be at risk at other times. Besides, the house with the shop was far away. After several attempts, we moved to “Pazarin e Ri”, in “Rrugicana Jani Vreto”, to the house of doctor Kirçik. Even today, this alley bears the same name.

It was a large two-story house. We lived on the first floor. There were nine rooms. Later, two uncles and aunts also came there. On the ground floor, there were medical clinics, one of which, that of my aunt’s husband, doctor Bajram Emir. The house also had a large terrace where we played.

Aunt Zyhraja came to our house often. She was a prominent activist of the National Liberation Front. She defended her idea even in the conversations she had with her father. But their opinions were often opposite. I heard my aunt say that; “Mustaqja” would win the war, while his father opposed him, saying that “Çibuku” would win. At that time, I did not know who “Mustaqja” and “Çibuku” were. Later I learned that it was about Stalin and Churchill.

One day, Gestapo forces followed Besim Levonje, an activist of the city’s guerilla units. He, running, was able to enter the alley and enter our house. He knew that his aunt also lived there. He had grown up in her house. Petrit, the aunt’s son, took him and locked him in a room. The German team entered the alley and began to look at the gates of the houses one by one. Our gate was the only one where families lived. They went inside and started going upstairs. At this time, Sabrija, Shyqyri’s wife, who had not seen anything, was passing by. He saw them and addressed him, quite calmly:

– “What happened? What is this?”?!

Her voice was clipped. The commander of the German team stopped and studied it. Her eyes showed that she really didn’t know anything. Something spoke loudly and then ordered them to leave. As the situation calmed down, Besimi was taken out through the yard of the Kirçiku family. We had school on “Pine Street”.

It was an elementary school. She was also called “Jani Vreto”. We had a very good teacher. They called him Dhimiter. I don’t remember his last name. He was a great patriot. He always spoke to us about the love we should have for our country. He constantly taught us patriotic songs.

One day, during arithmetic class, he saw a squad of German soldiers passing by on the road. He interrupted the explanation and told us to sing the song “Sa te rrov vellsia”. We all started under his guidance:

“As long as the universe lives,

As long as all the earth lives,

Albania will live,

Even the name Skenderbeut”!

Our song was followed by the other classes, which had windows facing the street. The Germans looked at us, but they did not stop the step. They continued the way they had started.

* * *

Those were the days of the Tirana war. The city, which was waiting for the dawn of freedom, lived uncertain days. People didn’t know who to protect before! To the German invaders who were leaving, or to the partisan “liberators” who were coming?! It was said that in the areas where the partisans were located, their patrols entered citizens’ houses, kidnapped and shot them, without holding any trial, without giving any explanation! And these cases were not rare.

On one of these nights, while we were sitting in the basement of the house, there was a loud knock on the door. This made the men look at each other.

– “Who can be at this hour”?! – asked the father.

– “I’m going to see,” said the mother.

The knocking was repeated more forcefully.

– “Who is it”?!

– “Open up, we are partisans”!

Mother opened the gate. Four armed partisans entered.

– “Why didn’t you open the gate immediately”?! – One of them, who apparently were the commander, asked in a harsh voice.

– “We were down in the basement and we didn’t hear.”

– “We want Doctor Kadri Kirčik”.

– “He doesn’t live here.”

– “Like that! Isn’t this his house?!

– “Yes, but now we live in rent.”

At this time, doctor Bajrami arrived, and after hearing what they were talking about, he said:

– “In case you need a doctor, I am one too and I am ready to help you”.

– “What is your name”?!

– “Bajram Emiri”.

The commander took out a letter from his pocket and began to read it. Then, shaking his head, he said:

– “No, no, we don’t need it. We love Dr. Kirçik. Do you tell us where you live?”

– “His house has an entrance from the side of the New Market”.

The partisans left. Bajram told Dawn:

– “Go quickly and tell the doctor to leave as soon as possible, because they are looking for him”!

Dawn ran away through a gate that connected our two yards and was able to alert the doctor before the partisans got there.

Bajrami returned to the cellar and said to Tim Eti:

– “They were looking for him to kill him. They wanted to kill him the way they killed Akil Sakiq, the prominent soldier who lives on “Pine Road”. Just as they killed the brothers Mumtaz and Vesim Kokalari, the well-known publishers of the “Albanian Message”. Just as they killed the prominent journalist, Nebil Çika, at the “Kursali” Cafe. But, thank you that we had time and informed Kadri.

Later, when I would be older and would get to know the sons of some of these victims, I would understand that it was a terrible massacre, which was a “gift” to the people of Tirana, on the eve of the departure of the Nazi invaders. A gift of thirty-eight shot, thirty-eight innocents. It was the replacement of the fascist dictatorship with the communist one.

A STORY ABOUT MY FRIEND

Live events

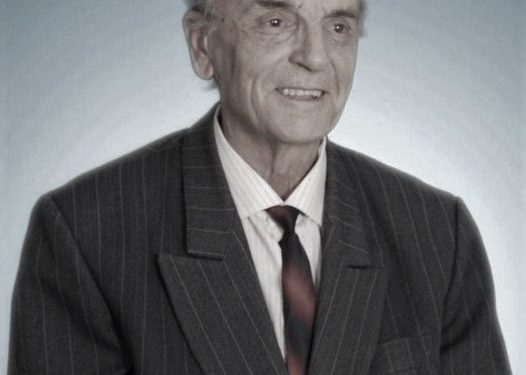

I met him in the forced labor camp of Ura Vajgurore, in August 1952. With an average and regular body, with a broad forehead like a scholar, with bright and hopeful eyes, with a sweet and measured speech, he was being a parent and a brother to me. I was only 16 years old, while he was 39. He called me “my little brother”, so I called him too; “my big brother”.

He finished his higher studies in Rome, at the Military University of Medicine, in 1938. He was awarded a doctorate in Medicine and Surgery with high results. Out of 100 possible points, it gets 97.

April 7, 1939, found in Tirana. He is one of the eight members of the youth commission, who went to look for weapons in the Royal Palace, but the King had already left.

In January 1940, while doing his internship, the Italian director of the Tirana hospital, Dr. Lozzi, introduced him to an Italian doctor, dressed in civilian clothes:

– “Il nostro giovane”!

The civilian held out his hand, which the doctor pretended not to notice:

– “Io sono Albanian”! – was his proud reply.

In 1941, he went to Italy for specialization. Someone proposes that you become a military doctor, on the Greco-Italian front, against a considerable salary. The doctor again refused. The results were; eight months of exile, on the small island of Capraia, at the mouth of the river Arno, in Florence.

In 1945, you find him in his clinic in Tirana. But communism, which had decided to become the gravedigger of the nationalist intelligentsia, took him to Gjirokastër, where at the end of December 1946, he was arrested. A few months ago, the investigator’s brother, Ferit, had died. After two years of torture in the interrogator, he is sentenced to life imprisonment.

This was the life of this man, until the moment I knew him. But here, I want to write about his great spiritual world, in those difficult years.

* * *

December 1952. After a tiring work, we were returning exhausted to the camp. A melting snow was falling, which soaked me to the core. It was chainsaw. I was shaking all over. When he saw me in this condition, he took me and laid me in what we called the infirmary. He put the thermometer on me. It showed over 40 degrees Celsius.

I will never forget that night, where my life fought tooth for tooth with death. In that war, the main protagonist was the doctor. I had fallen into a bracket state. All that night he stood over my head, constantly changing my napkins with cold water, the only means of cure he had at his disposal, besides some aspirin, or some other medicine.

In my bracket, I could hear his warm voice that was constantly talking to me, asking to give me strength and courage. He told me about his life and that of other friends like him. He told me about my parents, brothers and sisters. He talked to me about my school friends and I felt as if I had them close to me and I could hear their voices. Friends and brother did not allow them to come to see me. The order was clear. No prisoner was allowed to move from one silo to another at night. Finally, the doctor’s persistence won over death. Near morning, the temperature began to drop.

I had not yet recovered well when I was informed that I would be transferred to another camp the next day. The doctor protested to the command of the camp, but in vain, because the “drum” fell on deaf ears.

That night we hardly slept at all. I felt alone, abandoned. I felt like I had nowhere to lean on. The doctor talked to me, advised me. He told me that even there I would be among wise and wise men, on which I could rely. He mentioned to me the names of Xhevdet Kapshtica, Fatosh Kokoshi, Gjon Shllaku and many other men, heard.

I expressed my doubt, which I felt in those moments. I told him I was young and didn’t know how I would handle what was coming my way. Suddenly, he stood up and, in fluent French, recited Kornej’s famous lines from the tragedy “Sidi”:

“Je suis jeune, il est vraie!

Mais aux ames bien nais,

La valeur n’attend point,

Les nombres des annees”.

(“I’m young, it’s true, but for famous people, age doesn’t equal value”).

The effect of these words was immediate. A feeling of confidence began to fill my soul. He kept talking and talking while I listened with pleasure.

As luck would have it, after a month, they also brought him to our Vlashuk camp. We got together again.

* * *

February 1953. The six-year-old son of Lieutenant Adem, the camp’s cruel operative, was sick. The doctor visited him and did everything to save him, but no medicine helped. The only salvation was oleaginous penicillin, a recent and very effective but extremely rare drug that came from overseas. The lieutenant knew that a prisoner had one that his family had brought him and had not used. He begged the doctor servilely to ask him.

Suddenly the “wolf” had turned into a “sheep”. The doctor was convinced, only after receiving a promise from him, that he would return it within a month. The boy recovered, but along with his illness, the lieutenant also forgot the promise he had made. The “sheep” had turned back into a “wolf”!

After a while, Bejo Vrazhdua, from Bolena of Vlora, fell seriously ill. The only salvation was oleaginous penicillin. The doctor turned to the lieutenant, but he cynically refused, although he had found one. He protested to the camp commander, but he was also of the same dough. In early April, Bejua died. It was a day of mourning for the whole camp.

The most affected, the most revolted, was the doctor.

A prisoner, one of those types who can’t control himself, gave him a harsh opinion. The doctor replied:

– “I am a doctor. My job is to heal people, especially a child. One day this boy will be ashamed of his father’s gesture”.

I don’t know where this boy lives and what he thinks about his father, but if I met him, I would tell him that his life was built on the death of someone else, whose remains are not even known today.

* * *

Autumn of the same year. The storks were flying over the sky of the camp, preparing to return to their homeland. They all left but one. It was a weak and sick bird that could not fly. The “comrades” took him, lifted him up, but when they were convinced that he could no longer continue with them, they let him go and he fell in the camp yard. He was bloody.

The doctor took him and treated him. He quickly recovered. He baptized him with the name “Saip”, an Egyptian name, according to his origin. The bird became part of our family. He accompanied us every morning when we went to work and he came back with us in the evening. It was the only stork that spent that winter in Albania.

In the spring of 1954, we moved to Shtyllasi camp. We despaired that we would be separated from him. But we had only traveled a few kilometers when we noticed that our “Saipi” was flying over the cars we were traveling with.

He accompanied us to the destination. At the time when we were entering the camp, one of the guards accompanying us shot him with a rifle and he fell dead in the camp yard. The criminals did not even let the birds live freely. “Saipi” became the first victim of the Shtyllas camp.

Another bitter day. The doctor took it and put it in a cardboard box. The next day we buried him by the side of the canal, where we worked. Someone placed a poplar shoot on his grave.

* * *

Thoughts pass me one after the other. And who should I write about first?! For Vlashuk, where we worked at a depth of thirty meters, without even a defense, where Skenderi was killed, that the earth took him?! Or for Bulqiza, where for three days and nights, together with the doctor, we tried to discover the bodies of Mark and Vasili, who were covered by the mountain with stones, in the hope that maybe we could find them alive?! They don’t end. You can write whole pages, whole stories, and whole novels about them.

I will never forget the night of December 10, 1955. It was the last night of the prison. My friends stood around me, saying goodbye and wishing me well; complete path in life. Among them the doctor with his advices, which were not finished. Even today, they ring in my ears.

A few days ago, I met Mrs. Gjyla, his honorable wife. She was desperate for her son, only Enin, now a refugee in Italy. He went there to fulfill his and his father’s wish to study Medicine. There was nothing he could do. He felt powerless in front of that new and big world that surrounded him.

I remembered the distant night of December 1952, when the doctor recited Sid’s verses to me. How I would like to be at that moment, next to that boy! To talk to him, to advise him, to persuade him as his father used to do with me.

However, I am convinced that Eni will know how to find her own path in life. He will bravely move forward, just like his father, never forgotten, our beloved doctor, Isuf Hysenbegasi. Memorie.al