From Dhurata Hamzai

– The rare testimony of Edgar Prifti, former basketball player of “Partizan”, about his father, Robert, who for almost half a century, secretly wrote several novels, but never managed to publish them…!-

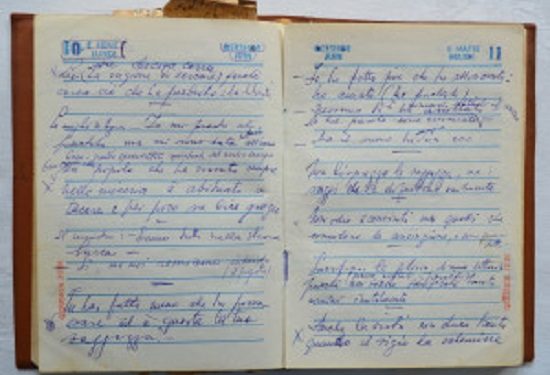

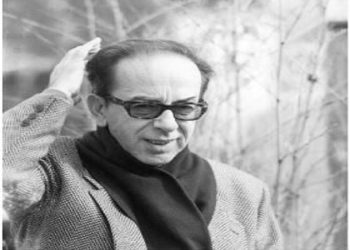

Memorie.al / Robert Prifti, started his creativity from the beginning of the 50s, in the Albania of the communist dictatorship, there, in the grip of some shooting or hanging on the rope, as if he resembled Vilson Blloshmi, Trifon Xhagjika, or Havzi Nela. Master of more than five languages, but also of a wide culture and rare knowledge, Robert Prifti wrote in secret places magnified transcripts, in the Italian language, under two pseudonyms “Robert Elin” and “Trevor Elin”. From finely conceived manuscripts, the literature of Robert the Priest would become known, after exiled clandestinely, to be published first in the languages in which it was written, mostly in Italian. Years later, some of the works were translated by his son, Edgar Prifti, into the Albanian language. In Italy, they have become the object of study, but in Tirana, there are few who have directed their attention to the literature of Robert Priest…!

But the memory clock is ticking again…! Robert’s son, Edgar Prifti, former basketball player of “Partizan” in the 80s, the team’s intelligent player, who was appreciated and sought after by foreign coaches, shirt number 4, who today holds the title of “Grand Master” – narrates in an exclusive interview, the odyssey of a rare creator of Albanian literature.

Edgar, I choose to speak beyond being the son of Robert Priest, where he gives us the opportunity to get to know a new branch of the history-writing of Albanian literature; the rare collection with 8 works, which is marked with the novels, “The Saint of Violence”, “The Sun of the Dead”, “The Eye of Polyphemus”, etc., with the philosophical works, with the poems, but also with other manuscripts awaiting new editions.

In the interview with Edgar Prifti, we have only taken the first step of recognizing a literature written underground, in the conditions of total lack of freedom of speech; where he tells us how he wrote about the dictatorship, seen through the lens of his father, Robert Prifti. The rest remains a phenomenon to be studied…!

Before we talk about Robert Priest, this unfortunately forgotten author, we are interested to know how his books were created.

– In the middle of the 50s and 60s, Roberti started writing, first (there are) some poems written with a pencil in Albanian and then, everything else he wrote only in Italian. Roberti knew eight languages, but since Albania was spiritually closer to Italy, he thought of writing these works in Italian and tried to publish his first novel; “The eye of Polyphemus”, rewritten, after the invitation came from his grandson, in a very small meticulous calligraphy, which he wrote with a magnifying glass. It was published in Albanian on 280 pages, while he had only written it on 16 sheets of D4.

This is an autobiographical novel, but through life it described the relationships between people, between groups of people, between party members of that time. Robert wanted to publish it at “Montadori” in Italy, not under his own name, but “Trevor Elin”. After that, the Italian cultural anthropologist, Mauro Geraci, who is researching the work and life of Robert and who will make an anthology book about him in Rome, he will better clarify, through the analysis he will make, when date these works, when he started them, when he wrote these poems or novels.

How was Robert’s life here in the Albania of the dictatorship, in that Albania that for the intellectuals, all kinds of situations were created, sometimes tragic, where we know something that even your family had upheavals in relations with the politics of the time?

– Robert was born in Korça, and when he was about two years old, his family moved to Tirana. He attended the lyceum of that time and then graduated in Bio-Chemistry and then he continued the two-year senior course in Bio-Chemistry, which was the University of the Time. Robert was taken after school, as a professor at the Bishop’s High School, for about a year and a half, where he taught all the main subjects there. It returned to the Institute of Scientific-Agricultural Research and then, it was sent to Maliq, for sugar beet analyses.

Then he moved back to Tirana and taught at the high schools “Ismail Qemali”, “Qemal Stafa”, “Partizani” and then it happened that he moved to Surrel, a village at the foot of Dajt, the reason being that in a meeting of the Pedagogical Council he was speaks for the teaching reforms, so that the most progressive methods are taken and borrowed.

And so Robert had a solid foundation of ancient Greek, Latin, while he learned Italian in high school, and then he knew German and Spanish, etc. He was self-taught. He never went abroad, except in ’87, when he tried to publish this novel, which he had rewritten in 16 pages, he had put it under his bag, in order to pass it through customs, so as not to be caught.

You were also familiar with German, in terms of your mother’s origins, right? Tell us the story of your branch of the family and of other Albanian families, since marriages with foreigners created a situation where they were more closely watched by the dictatorial system?

-My grandfather on my mother’s side, his name was Luigj Kodheli, who finished his studies in Finance in Italy. He returned and in 1911 participated in the Koplik war, and then in 1913 he participated in the Congress of Trieste, where the fate of the homeland was also discussed. And it is a whole list, where the name of Luigj Kodheli is also there, together with Hilë Mosi, Fan Noli, and other compatriots. In 1920, he took part in the battle of the Great Highlands.

These are documented, because in the newspapers of that time, it is written that when Luigj Kodheli died, MP Kolë Mjeda, cited his patriotic values, and when he caught a severe cold, then the Presidency of the Presidency of the Republic of that time, took to Gavos in Switzerland, to cure, but he could not and died in 1930. I have followed many documents of that time; he has been evaluated as General Inspector of the Presidency of the Republic.

He was devoted to work. They loved him, even so much that, as the aunt says, the people of Shkodra did not let him be taken in a carriage to the Catholic Tombs, but they carried him on their shoulders all the way there…! So how did Louis meet Robert’s mother-in-law? Maria was German, but from an annexed province of Czechoslovakia. The grandmother came to Albania, after finishing high school, with an aid mission. It was World War II time then.

That’s how she met Luigji and, after they got married, four more daughters were born: Rozmarina Kodheli, then there was Kerina, Gizela, and Luigjina Kodheli. Kerina and Gizela, unfortunately, died. My mother graduated from the University in Romania, for agronomy engineering, but my mother fell ill and fell into a coma when I was 12 years old and Roberti was 41, and she remained paralyzed for another 38 years.

Painful event…!

….But we also had an aunt. They lived in a house with their aunt. My aunt played the piano wonderfully. It was said that they would take him to study in Hungary. But someone else would take her place. Robert lived in a house, amidst the sounds of Bach, Debussy, Smetana, Mozart, Liszt, Tchaikovsky and the library that was filled with collections of Goethe, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Freud, etc

And the writer, from what social circumstances or social environments, was she inspired for Robert?

-Roberti was young and seeing that many things did not go well, so the opposite of what was said happened, the opposite was done; he, who was 18-19 years old, was a sympathizer of “Balli Kombëtar”, and he tried to do something. So he started writing and analyzed the phenomena, and not only that, but he also analyzed the language, created neologisms in Italian, where there are countless notes. So there is a whole suitcase, with his manuscripts.

I am referring to the book “The Saint of Violence”, where it seems that what he felt about the time, about the regime, was a very internal and very special conviction even for the intellectuals of the time, because there was something beyond the analysis that is done to him regime, an analysis that not only talks about the circumstances of what we experienced here in Albania, but also about the worldwide circumstances. So, his book talks about the whole impasse that happened to Europe and the world after the end of the two wars, it is an analysis almost of a sociologist, philosopher, but there is also a sense of the writer, which is visible everywhere. What period does his work belong to? Can you somehow divide it, since you are also involved in the translation of books, into several creative stages?

– Robert has experienced all the time. He was young at the time of liberation and died in 1993. But how has Robert’s mentality and worldview begun to change?! This can be seen in the letter from 1952, when he was working in Korça, he used to send letters to his friend in Italian. They were not married, in 1953 they got married. They are very interesting papers. Robert didn’t date anything, and dividing the works by period is, for me and many people of letters, difficult.

But not only me, also are Italian researchers, who have started to study Robert’s work, interested to know. Perhaps these letters, which came to light only after his death, if they are submitted to a chemical analysis of the ink, or of the paper, that he used where all kinds of letters, can be dated, but he wrote secretly, he often went to the Church of Saint Prokopit, near Liqeni, used to go to Durrës to write.

Where did he get these letters? Did no one see it? Because we know the history of writers who wrote beyond the administrative concept of dictatorship in Albania, where they were shot or imprisoned just for that?

-These letters, these manuscripts, were found after his death. I was in Germany when my father died. My cousins buried him and for that I am grateful. George Mita, (the husband of one of my uncle’s daughters), had collected them and I was surprised when I saw them. I remember the last phone call from Robert, when he took me on the phone and said: “I’m very upset”, and further; “I will be happy to publish my works”. It was his dream that he had had for decades. But I didn’t know these. Now that I see them, I dare not get into his shoes.

He kept me away from all this. He didn’t want to confuse me. He read forbidden books, and kept them hidden. When I said: “Where do you find these books”?! He said: “You don’t need anything”! Because he was worried that I wouldn’t tell my friends and I would have problems. Apparently, he hid the manuscripts and books in a storeroom of the house that we had outside, with rulers and work tools, and how many times he said that; “I will get some wood”. But there was wood in the house. He brought wood, but was late when he came.

So, for years, he hid everything. When I checked in the multitude of manuscripts, I discovered that he wrote a lot of poems, titled and untitled, because he did not manage to systematize them, he passed away. His manuscripts contain about 400 poems. The third volume contains his aphorisms and thoughts, where in one of them, he says: “The homeland for him is not where the right is, but where he was born, there and he dies for the right”! At a time when he went to Italy, I told him: “Now, father, stay in Italy, don’t come back.” “No, Eddie, he told me. – I will try to publish the book and I will return”!

Meanwhile, there is another aphorism expressed in an imaginary dialogue with a skeptic. The skeptic asks him: – “You have not done as much as you could not dare, is this your wisdom”? Robert answers: – “I have done more than you would have dared to do.” I have spoken. I fell in love”. The skeptic: – “Your words have been censored, no one has heard them, they only hear the sound”! Robert answers: – “But the sound always has an echo…”!

So this is the story of a work that was published posthumously and of course, that has very good messages. Robert Prifti, who was not lucky enough to be one of the great Albanian writers during the dictatorship, not because he wasn’t, but because he wanted to write in his own original way,. Meanwhile, he had a pride of his own, which was you, a well-known character for the time. How did you get into the world of sports? What did your father feel, during that period when you were involved in sports and you were successful, of course. Were you a household name?

– Eh, the father certainly received it well, when I told him once, that they told me to join basketball. “Of course”! – He told me, but I had a period of interruption, because once, he saw me in Durrës and said: “You are black, you will leave the sport”! “How do I leave it”? -I told…! Then I had a severe cold, I was told that I had an enlarged heart, but with the constant visits and persistence of the coaches, I returned to the sport. But he was not a fan of “Partizan”, with whom I played, he was a fan of “17 November”, and he wanted to win, but he did not regret that I was with “Partizan”.

However, “Partizani” was more famous in that period, was it the most popular among the admired teams?

– Of course, but he also had his pride contained, and his praises were contained. He never beat his shoulders for what he was. He was modest.

In the outings abroad, I have learned that you have received special evaluations, for the strategies of your basketball game…

-Eeh, it was really backwards time. We played really, really good basketball for that time, for the conditions we had in Albania. Even some of our players could play successfully abroad. They asked me to play in France; they also asked me to play with “Eczacıbası”. However, it was impossible to quote these proposals, let alone implement them. Of course! But that was the time. But we struggled in those evil times and it was probably one of the only lights, where people looked at a space, sports. They gave a show. That is, we tried in our own way to give freedom to sports fans within those frames, within those walls of the Sports Palace.

Let’s go back to your father’s work, because this is also the main topic of this interview. Regarding the work you have done, what should be done next, not only by you as an individual, but also by the institutions?

– In 1994, after I went to Germany, it was the first time I came back and took the suitcase in hand. I saw a bunch of manuscripts, but I had absolutely no time to start working on them. That is, the time of the start of work dates back to October 2007. Then the company where I worked was dissolved. What my father had written on the typewriter, I retyped on the computer. After rewriting a novel page, I opened the next page, where I translated from Italian to Albanian.

Aren’t you afraid that you somehow damage the style, that linguistic nuance that comes to the creator, unlike the linguistic meaning?!

-I understand you. I tried to put his manuscripts on the computer once, but Amik Kasoruho, who was a friend of ours, when he found out about Robert’s work, told me; “Why don’t you return Robert’s work to Albania”? “How do I translate it? – I told. “If you translate it,” he said, “I can’t translate it, I have a lot of work to do.” I’ll edit it, I’ll send it back.” And then I started. I was very tired, but it was a pleasure, that I had the opportunity to talk with my father and it seemed to take away that tiredness. Robert only asked for participation. He did it just to participate, to tell the world about what was happening in Albania, risking his life.

I was telling him; “Dad, what is he doing like this”?! But he used to tell me, “Eddie, they caught me, don’t look for me anywhere”! He knew things very well, and thinking this, I have not continued this work, for a whim of mine, or my name. I consider it a mission, so that we don’t forget, that there were people who thought differently, to have this Albania, better, who were patriots. I know this, as if even people, who belonged to those who were in charge, knew that their fathers were wrong…! But the smile will return to this country, as Robert said. Memorie.al