By Ani Jaupaj

Confession: “Our brother escaped from Albania, fled on foot, from Dajti to Yugoslavia, but we did not suffer economically, because we received money from the USA”

Memorie.al / Suzana, Handani and Nermini, today they are advanced in age, but once, girls from a wealthy family, they each had a talent: in tennis, music and foreign languages. Even though they belonged to the former dictator Enver Hoxha, after the escape of his brother, they would be exiled to the village of Savër in Lushnje. From what little they remember, they tell the times when Enver Hoxha used to go in and out of their house, door to door in the Palorto neighborhood in Gjirokastër, to listen to the radio on foreign stations. While his father, uncle Mullai, administered the properties they had in the stone city. Even today, the one who is the oldest among the three sisters, Handan Hoxha, the first female tennis player in Albania, continues to be at the center of all the movements at home.

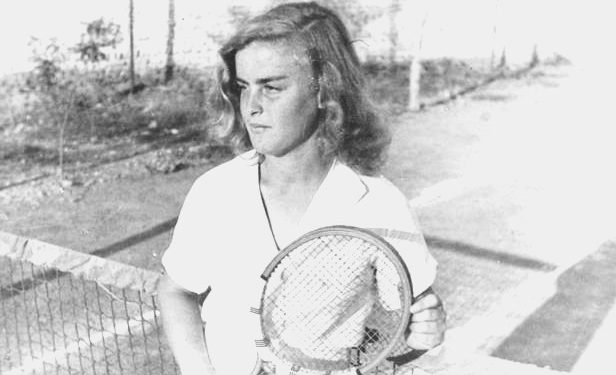

Even though 85 years of her life have passed, she has remained the most agile. It’s the one that gets up first if a door needs to be closed, if friends need to be surprised with rent, if an old photo needs to be found in childhood chests… it’s the most elegant. The 15 years she has been involved in sports have still left marks on her physique. The older sister, Suzana, otherwise Suzi, as everyone calls her, was once a teacher of solfeggio theory at the “Jordan Misja” Artistic High School in Tirana. The youngest, Nermini, has always dealt with foreign languages.

Even today, on the verge of 80, he continues to have 2 students to whom he teaches English. The three sisters, once, so many years away, that it is hard for them to remember, lived happily in their big house, right next to the Artistic High School. They learned foreign languages, with a private teacher, took sports lessons, spent their vacations in one of the only 4 villas on the beach of Durrës, until everything was interrupted, as if by a knife. The manors inherited from the grandfather had their golden time for a very short time!

The dictatorship would steal everything from them, houses and manors, even though, as can be guessed from their last name, Hoxha, they were relatives of the former Albanian communist dictator. With the houses facing each other in Gjirokastër, the common origin, and family in and out, from him they took the only “dowry” that the three of them had in their lives, 30 years and 6 months of internment. Neither of them ever married. They have been living for 23 years, since they returned from the village of Savër i Lushnja, in the palace apartment that was built on the land of their former villa, which their father had built. They have few powers, the desire to return to the evil times, as well.

However, after much insistence, they agree to speak, repeatedly saying that; “we need calm, we don’t want interviews”. However, they return once again to those years that are already hazy to them, because they date back to the time of the Bird…, when their life was bright. Questions are mostly answered by the eldest, Suzi. In case he didn’t hear it well, Nermini intervenes to repeat it once more. While Handani, sits almost without speaking in her comfortable armchair. She comes alive only when it comes to sports, mainly tennis, and her first and only love.

“What did we do” was that of your ancestors, which condemned you for 30 years?

It was 30 years and 6 months (the three intervene to clarify, almost as one voice). It was the end of 1959, when the police truck came to the house, loaded us to transfer us to Savër in Lushnja.

Where did the persecution come from you, from your father, grandfather…

In fact, the story starts with the grandfather, although the last reason was from the brother. Our grandfather had graduated from law school in Turkey, he came from a rich family and his father also studied in Ioannina, at the “Zosimea” school. From this, but also from the books that my grandfather secretly provided, my father was among the first teachers in Gjirokastër. The former dictator (Enver Hoxha) also mentions in his memoirs that he received his first lessons from his father: “Our first teacher was a certain Vehip Hoxha, who was the son of Asaf Efendi, a kadi, a very learned man.

They lived near our house; we were from the same tribe. Where Mr. Vehip learned Albanian, I don’t know, but certainly from the primers of Istanbul and secretly. At that time, Mr. Vehip was a resourceful, enterprising and resourceful boy. He had a great desire to teach us”, as he writes verbatim. Then, the father moved to Korçë, where he worked as a bank manager during the 30s, and then he came to Tirana, as a senior employee at the National Bank, where he was in charge of the Treasury.

From what is written and from what do you say, wealth was the first “damage”…?!

Yes, but it didn’t show up right away. We lived for a few years well, as we were always used to. We learned foreign languages with private teachers, we always went on vacations, and we played sports. Handani was very good at tennis, the first Albanian woman to practice this sport, she trained with Sali Nallban. She only had that dream, to become the best tennis player and represent her country in international competitions. But, in addition, he also played basketball, volleyball, table tennis. So much so that our brother made a small table tennis court, which we put in the backyard.

Wasn’t all this freedom that your father gave you too much for the time?

Understand that the people around father were all aristocrats, even those who played tennis. Even today, tennis is still considered the sport of the upper classes, not everyone plays it. Nothing stands in their way these days, but the fact that they don’t means something. Everyone has played basketball or volleyball at least once, but not tennis. Being always surrounded by such people, it didn’t feel like we were doing anything “undone”.

Of course, there could be some occasion that brought word to the father, what were all these luxuries, that he was teaching us, but he was completely indifferent. Our father was “modernisimo” (from the Italian, very modern), Handani hastens to add, since the conversation was focused on sports, the only point where her indifference, already from age, was teased}

All this happened before ’44, didn’t it?

Yes, but even a few years later, despite not playing sports, we lived well. I (Suzi) studied at Lyceum and managed to graduate. It was there that I started to teach and, with great difficulty, created the first book of solfege lessons in Albania. A book that, of course, was taken out of circulation when we were exiled. I met my former students after 90, who thanked me for the opportunity I gave them with that book. Then I learned with the Soviets, because Nermini knew Russian well and helped me with translations.

When did the first tremors occur?

Immediately after the advent of communism. At that time, my father had come to Tirana, to the National Bank. Already at that time, they tried to put him in prison twice, but they didn’t succeed. We were unwanted from the beginning, because we were not a poor family, this was our “flaw”. I remember that the director of the National Bank, at that time, was an Italian, who told my father “come to Italy, don’t stay here, because you have property, they will always have you in their eyes”, and in fact that is what happened. They immediately removed him from his position and left him as an accountant to begin with. Then, in ’51, they came and took us from the villa that my father had built; they took us to Ali Bege’s house.

I remember that Enver’s father, the desolate Uncle Mulla, came home, as I remember him today. His mouth was full, even when he got nervous, he would run away. “Where, where, where, are you taking them”, he told them. Uncle Mullai was a very good man; he was the one who managed the wealth we had in Gjirokastra, before they took it from us. Our house in the “Palorto” neighborhood, in front of his, which in those times was exactly the same as the others, and then when it was his turn to ascend the throne, he did as he wanted. Neyse, he didn’t ask what your father said; he killed and cut the people of his door, not us.

And you were also with him, had you had family in-and-out?

At the time that his father worked as a bank manager in Korçë, Enveri was at the French High School. Of course, the acquaintance between the two had been since Enveri was a child, for this reason, since we were close and even though he was a boy from Gjirokastra, he always came to the house, his mother told us. She cooked for him, and for the other boys, like; Vedat Kokona, our aunt’s son, Asllan Beja (father of Fatos Beja, former deputy and vice-president of the Parliament, a few years ago), brother of Liri Gegë, etc., who visited the house to read, get a book or listen to foreign stations on the radio. They spoke French and Italian, even the radios were stationed on these signals.

When were you interned, in Savër…?

As we told you, we lived for several years in the houses of Ali Bege, here in Tirana, and then another event happened. Our brother, who, like all of us, did not accept anything from that regime, escaped. At first, he bought a motor, so that he could put a small boat on it and escape from the sea, but since he was in danger of being spied on, he fled on foot. As he told us, when we met after 1990, he had fled from Mount Dajti, on foot, to Yugoslavia. We were not immediately taken to Savar. They left us for 2 months because they were trying to use the father for some information. They saw that nothing happened; they put us in the truck and took us to Lushnje.

Anyone would try, at least for the acquaintances and friendship they had, to intervene to save all of this, even if they failed. Did your father do this?

No, never, he surrendered to his fate and did not even take the trouble. Especially, after he found out that the brother had arrived safely at our uncle’s home in America, who had fled before the Liberation.

How did you find out, where did you get the information from?

Uncle used to send coded letters and we understood. For example, the announcement of the arrival of Asaf (that’s what the brother was called, he had taken the name of his grandfather) was: “Drita gave birth to a boy, he is healthy”. Together with the pieces of paper, we also received money, which made it possible for us not to suffer the exile like others, but to live relatively well. With what we heard later or, even at that time, about the camps of Tepelena and Porto Palermo, we say that we would surely have died.

Did you work abroad?

Father no, he tried to plant wheat once, but he didn’t know and they didn’t take it anymore. Mom doesn’t. Handani went out one day and at dinner said, let Enver Hoxha come here himself, shoot me, I don’t go to work anymore. Nermini and I, we saw what we saw, that you are drawing attention to us, why the Hoxha family was not working, and we went to work, but not because we needed money. We worked on cotton gins, work that I did not find difficult, because I had nimble finger movements, from the piano. Then in the arrangement of cash registers and so on… not difficult jobs.

From what you say, a certain tolerance is felt. If they wanted to, after escaping, they could have done much more to you. Does this have anything to do with your last name?

(The three sisters laugh. Who earlier and who later, because not all three could hear the question due to poor hearing. But when they understood it, their reactions were immediate and all the same, because of the memory that came back to them, like it was yesterday.)

Based on the last name, the father was asked and always said that he was Enver Hoxha’s uncle and that his son was not a fugitive, but was sent by the state to America, that’s why we also had facilities. The father objected as much as he objected, then said; “Yes, I am his uncle.” When we asked him what he said, he replied: “Well, I did well, let him be ashamed, as he shamed us.”

In 30 years, there was no event that moved the waters, gave you a hope?

There was, after 6 years. Demek released us; they gave us a passport that showed that we could move to all cities, except Tirana. Suzi (Nermini tells) went to Durrës, where she started again as a music teacher and meanwhile, she was trying to find a house to attract us too. During these efforts, I had a toothache and the dentist told me that I should take an x-ray, which was only possible in Tirana. Not to make it long, after many adventures, I get the permit and leave. On the way, somewhere from Rrogozhina, they stop me and call me to the Internal Branch.

I was asked to become part of the Communist Secret Services (State Security). What I heard up and down, I would report. After they told me and I refused, I learned that they had done the same with my father, so they were pretending to take us out of exile. This was the only event, Suzi was returned to Savër, the father died a year later, and we remained 4 women there. But at least we didn’t need the money. Yes, the 4 of us, we came out of exile and came to this house where we live today. Mom died in ’94.

What about the villain, when did you meet him?

As soon as the opportunities arose, after 1991, he came with his family. We also went to Savër together, because he wanted to see where we had lived all those years. Then, later, we came and went often to America, like us, like him.

When you were interned, all three of you were young, beautiful and educated girls. Did you leave half a love story in Tirana?

No, then we thought it was early, precisely because of this emancipation that we had, unlike the others. We devoted ourselves to work and entertainment.

What about there, in Lushnja? 30 years is a lifetime…! Neither of you made any connections…?!

No. There, no. We were taught differently, the level of our fellow sufferers was quite different from ours. It also happened that they asked us to marry in exile, but none of them accepted. We made up our minds that we will live alone and, as you can see, that are what we did.

To the man, marriage seemed the farthest topic from all that we had talked about. Youth is just as distant, when for sure, for everyone, more or less, the stomach is narrowed and the mind does numbers. They don’t remember anything. The three of them live with each other’s houses. Handan, whose name, from Arabic, translates as “optimistic, smiling”, is indeed the funniest among the three. Nermin is the qibara, while Suzan is the fiery one (all three names have no hyphen, so no final vowel). Father, Arabic names were chosen from those who, for the first time, sound like men, but whose meanings seem to dictate their lives. The qualities of one compensated for the shortcomings of the other. Otherwise, coexistence for more than 80 years would not exist. /Memorie.al