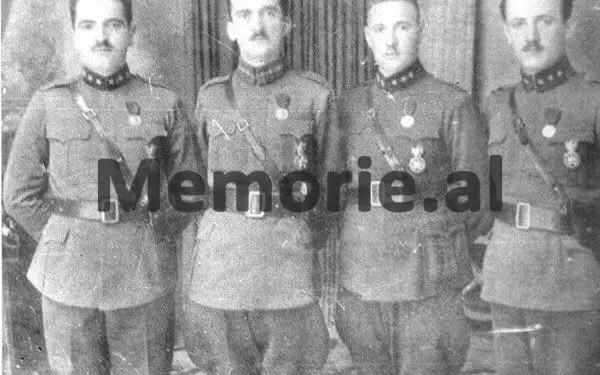

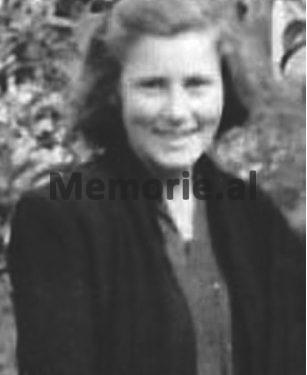

– “My tragic life in the Albanian ‘Gulagun'”, the story of Rudina Dema, daughter of Colonel Hysni Dema, former Commander of the Gendarmerie during the period of the Zogu Monarchy and the occupation of the country, who with the arrival of the communists in power, was forced to escape from Albania and his family, his wife, Vasfie, with daughters, Tefta, Vera and Rudina and two sons, Sazani and Aliu, suffered long persecution in exile, until 1991-

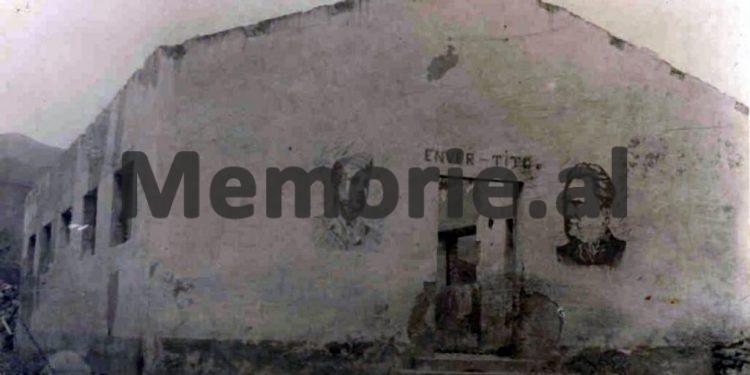

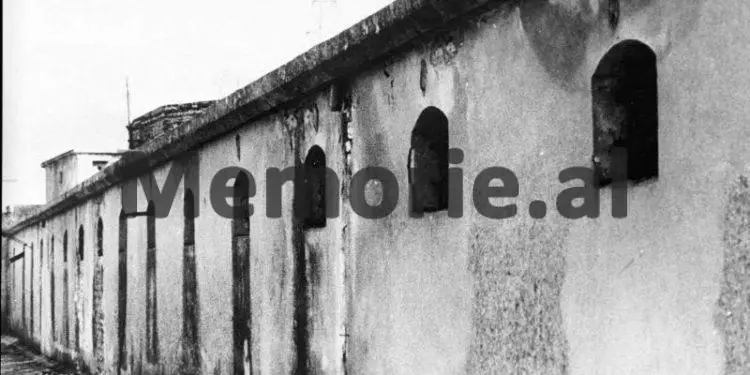

Memorie.al / In a huge pile of dirt and yellow grass, dry, burnt by the sun, the entrance gate opens in front, it is all rusted and just beyond there are two buildings, which are collapsing. On its sides stand several buildings, also stripped of time. They no longer have doors or windows. just a few pieces of brick inside. This is how the Tepelena concentration camp appears, in the south of Albania. In these ruins, built by the Italian army, during the Second World War. The Albanian communist regime closed hundreds of families between 1949 and 1954: mothers, brothers, wives and children, hated by Enver Hoxha, the dictator of Tirana.

The prisoners were housed in large common rooms. They slept on hard wooden planks in the heat of summer and the cold of winter. Forced labor was a massacre. “We would climb the mountains behind the camp, saw down the trees, load wood on our backs, heavy bundles for the women, big logs for the men, and carry them back to the camp. Unsafe hygienic conditions and poor food added to the difficulties. Many prisoners lost their lives. Three hundred children who didn’t make it”, says Rudina.

A small memorial with white stones, in the middle of the greenery, as if paying tribute to the victims. The camp was disbanded after the United Nations denounced the inhumane conditions for more than three thousand prisoners. After leaving this camp, their fate did not change. They continued to be used in other areas, especially in those around the city of Lushnja in Central Albania.

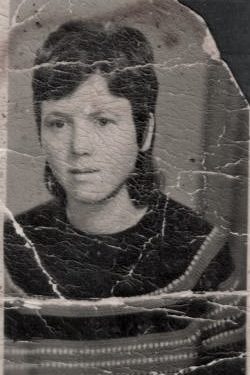

Rudina Dema, born in 1945, managed to survive the hell of Tepelena. She entered the camp in 1949, staying there for two years.

Memories of that experience are dim, yet certain episodes are firmly fixed in the head. “We lined up with a cup in hand, like in the movies about Jews in concentration camps. They filled those cups with strong wheat soup. Sometimes we found worms there,” she recalls.

And then he talks about the relationships with the other children in the camp: “We made clay balls and threw them at each other. In the barracks we slept next to each other, tightly packed like sardines”.

I met Rudina on August 30, 2017, during a commemoration organized in Tepelena by the ‘Authority for Information on Former State Security Documents 1944-1991’, the government agency that, since 2016, has delved into the repressive history of the regime most paranoid and violent in communist Europe.

That regime sentenced hundreds of people to death and covered the territory with forced labor camps and prisons, as well as setting up an apparatus of security and repression, the Security was based on a gigantic network of collaborators. Everyone spied on everyone; so many skeletons in the closet.

Memory, therefore, has remained a sensitive issue even after the end of communism in 1991. The victims of the regime have remained marginalized, keeping everything inside. Only now can they begin to publicly share their suffering.

Those of Rudina Dema are not limited to Tepelena, where she spent a long part of her life in forced labor camps or probation. In 1985, when the dictator Hoxha died and the political context became less rigid, Ramiz Alia, the successor, prepared some reforms opening to the outside world, but still limited. However, Rudina continued to live in fear, that the regime could turn against her again.

So, in 1991, when the large landings of Albanians to Italy began, at the beginning of March she, her husband Haxhiu and her three-year-old daughter Maggie, boarded one of the cargo ships, which left Durrës for Brindisi.

Albanian communism was collapsing and precisely the government of Tirana no longer controlled anything about it. But Rudina thought that the regime in power would be able to restore order and perhaps cause a wave of arrests. Italy was an opportunity to start over and she wanted to take that chance.

A few months after landing, again in 1991, Rudina, Haxhiu and Megi settled in Rieti. They have never moved from there. Today they live in a modest social housing. With them is Tommaso, the son Maggie gave birth to ten years ago.

In Tepelena, Rudina had briefly summarized her history for me, mentioning the historical-political twists and turns of communist Albania, which I was not able to fully understand, not having enough knowledge about them.

However, the strength of her words and eyes, a little sad but very insightful, had convinced me that this story deserved to be heard. And so I went to Rieti, twice, to understand and frame it better.

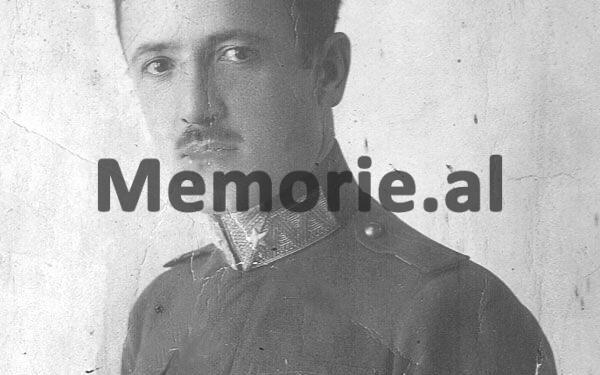

Rudina is one of the five children of Hysni Dema, former colonel of Zogu’s army, King of Albania. When Fascist Italy invaded Albania in 1939, Colonel Dema was exiled to Tuscany, Italy. He returned to his homeland in 1942 and assumed important roles in the ‘National Front’, the nationalist organization which, creating a tactical alliance with the Nazi occupier, who replaced the Italian one in 1943, tried to thwart Enver Hoxha’s partisans to take power.

Failed attempt. Hoxha liberated Albania in 1944, establishing himself as autocrat. Dema first went into hiding, then managed to escape the country and take refuge in Greece, where he died under still unclear circumstances in 1954.

“My mother was pregnant with me when my father ran away. I have not known and have no idea what fatherly love is. When I hear Megi, who addresses Haxhi as father, I think: “But what does this mean? What does it mean?” I was very angry with that father, whom I never saw, .

I had a painful life, no toys, no fairy tales, no freedom. I used to tell my mother, Vasfia, that a good father should never leave his wife and children alone. She got angry, threw a slap at me and shouted: “Aren’t you ashamed?”

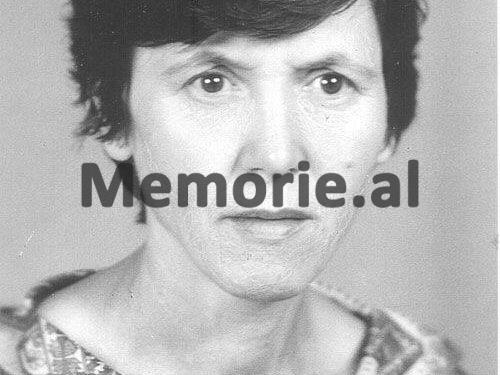

Hysni Dema is the “burden” of Rudina, her mother and her brothers, all older than her: Tefta (1927), Vera (1930), Aliu (1933) and Sazani (1935). In Enver Hoxha’s Albania, an “enemy of the people”, a “conspirator”, infected the whole family with his status.

“After they took power, the communists knocked on the door of our big house in Tirana, they asked to take us out. She went with Vera, Ali and Sazan, to the house of Tefta and her husband Shaqir Muça. I was born there, on February 20, 1945”, remembers Rudina.

A few months after the birth of Rudina, the Dema family was transferred to a forced labor camp in Berat. Their previous life, quiet and comfortable, would never return. “They loaded us into the truck like watermelons and took us away. They spared Tefta, only that she was married and no longer appeared in our family nucleus”, says Rudina.

During the next three years, Vasfia and her children were moved to different camps: Porto Palermo, Four-Rugët e Shijaku, a place near Durrës and Kruja.

Then in 1949 they came to Tepelena. A world apart, terrible. Tefta could no longer visit them like in the camps where they had been before, this was impossible in this camp. From the missed meetings with him, Rudina has a good memory. Of the children who died in the camp, however, no: “I only heard the desperate cries of the mothers,” she says.

In early 1951, Hoxha’s communist regime decided to release all the children of Tepelena, plus some not so politically “contaminated” prisoners. Rudina left the camp; her family members stayed there.

“My mother entrusted me to a family in Kruja, among those released from prison. It was the first days of March. They forced us to board military trucks and took us to Tirana. We arrived at night, it was very cold and raining.

They took us to “Skënderbej” Square, right in the center and dropped us off in front of the mosque. We slept in front of the mosque, under its shelter. Early in the morning, the Imam and the head of the family came from Kruja, i.e. the head of the family, I’m ashamed to tell you, but I don’t remember the name, he explained who I was, asking him to take me to Tefta”. The Muslim cleric assured him that he would do his best, but first he had to recite the prayers. After it was over, he and Rudina went to the bazaar, which at that time was held on one side of the square. He stopped at the stall of a merchant who sold hats. He had been a neighbor of the Bulls and knew them very well. The Imam described the situation to him and he took his son out to find Tefta. “While we were waiting, he gave me a cup of milk with some bread. I ate it hungry, like an animal, I was so hungry”, Rudina remembers. A little later, Tefta came and Rudina jumped into his arms. “My sister immediately took me to a barber to cut my hair: it was full of lice.”

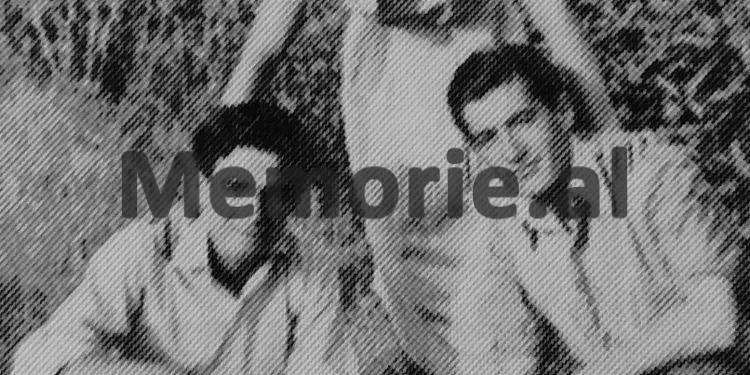

The two sisters were united, but for Tefta that joy could not be absolute. She was going through very difficult times. Just a few days before Rudina’s arrival, more precisely on March 1, Leone Cieno, the Italian engineer with whom she was connected after the premature end of her marriage with Shaqir Muça, was deported to Italy. He arrived in Albania during the fascist occupation.

After the war it remained: good techniques were needed for reconstruction. His life changed on February 19, 1951, the day a bomb exploded in the courtyard of the Soviet embassy: the scene with which the regime launched a severe purge against Italian intellectuals and residents, all accused of being in the service of Western imperialism. Cieno was kicked out and Tefta was left alone, eight months pregnant. On March 31, a son was born. His name was Pierino.

For several years, Leone and Tefta maintained a correspondence. She sent photos of Pierino growing up; and he sent him some money. Then Albania chose the path of total isolation and all communication with the outside world was banned. Leone heard nothing more about Tefta and Pierino.

He did not forget them, but rebuilt his life in Sardinia, marrying another woman. Pierino grew up without a father, like Rudina. “He only knew his father in 1990, going to Italy for the first time, before settling permanently in 1991. Tefta, on the other hand, never saw Leone again, as he died shortly before she too emigrated in 1993”, says Rudina.

After Leone’s breakthrough in Italy, Tefta found herself with a son to raise alone and Rudina to take care of. She was formally free, but the State Security kept her under surveillance and once provoked her: “One night some officers entered the apartment. They asked some questions. One of them lit a cigarette; that glowed in the dark. They left after a while. Life for Tefta became difficult. She was convinced that sooner or later, the regime would hurt her, me and Pierino.

So, emotionally exhausted, she made a drastic decision. At the end of 1954, we joined my mother and brothers in the Plow camp, near Lushnja, where they had been transferred after the closure of the Tepelena camp. As soon as we arrived there, the camp authorities told Tefta that she could stay, but she would have to call for appeals every day, like all the other prisoners,” Rudina recalls.

She had to give up her freedom, in other words. It was the same for Rudina and Pierino. “My sister was aware of what awaited us, but her life, with State Security under surveillance, had become unbearable. She thought that if we really had to suffer, it was better to do it with our loved ones, sharing the same fate with them.”

“It seems strange to me that we are in Italy, that we have a car and we have running water and washing machines at home. I observe these things with curiosity, like a little girl. Maybe it comes from the fact that my childhood, which never started, is somewhere inside me, even if I’m already old,” says Rudina.

Childhood and adolescence: the regime also took that away from Rudina Dema. She spent it all in the Savra camp, where she would stay until 1964. She and her family arrived there after a couple of years in Plow.

Savra was also located in the district of Lushnja. During the day Rudina worked the land for an agricultural cooperative, while in the evening she attended school. He got his high school diploma with many sacrifices. A miserable, difficult life. This camp was better than the one in Tepelena.

“There all the prisoners were in one big room. In Savër, they gave us a room for ourselves, for me and my family. It was inside a shed. We didn’t have a bathroom, we had to go to the yard. But at least we were alone”, remembers Rudina.

Their brother Sazani, in 1951, immediately after the release of Rudina from the camp, manages to escape from Tepelena. “He was fast, he was sixteen, he found a way to escape the control of the guards.” He was immediately caught and served four years in prison in Gjirokastër. After he was released, he managed to escape to Yugoslavia. Then he went to Greece, Italy and Germany. Finally in the United States. He lives in Missouri and is a US citizen.

After Sazan’s escape, Vasfie’s mother was tortured by the State Security. “They hung her upside down from a tree, placing a bucket full of m… in front of her face. Tell us where your son is, or we will put you in there,” they threatened. But she did not know, and the guards did not have the courage to act further.

She suffered another humiliation in the village of Plug in Lushnje where she was interned, when State Security agents informed them of the death of her husband Hysniu. “He died in Greece”, they said with contempt. They used that very word: died.

In 1964, the communist government of Tirana somewhat eased the control of political prisoners with a trial measure. Beneficiaries could live and find a job within safe zones, restricted by the relevant authorities of the Ministry of Internal Affairs who supervised them.

Rudina and Tefta benefited from those facilitating provisions. Aliu and Vasfia did not apply for relief measures and remained in Savër. Vera, on the other hand, had been in Tirana for some time, where she was married to Qazim Kuça, a driver in a fleet of transport trucks. Even his family members had problems with the regime and knew the Dema family. The authorities gave Vera permission to leave the Savra camp and live with Qazim. Love, at least this one, was not forbidden. Not always. In 1968, the couple had a son, Angel.

The area within which Tefta and Rudina could enjoy the “trial service”, (as an interned family), was included between the cities of Lushnjë, Fier, Berat e Kavajë and Elbasan. They chose to go with the latter. “Tefta believed that in that city, a big city with a good cultural base, we could find a decent job and live-in peace”, recalls Rudina.

Between expectations and reality, the difference was profound. “It was not easy to find a good job, as we had a compromised reputation for the communist regime in power. We found work only in the olive groves of the area and later in a tailor shop as laborers. Every day, in the morning and in the evening, we went to the Department of Internal Affairs to present ourselves, as was the rule for internees. Afterwards, the locals’ opinion towards us started to deteriorate and the most indoctrinated fanatics called us: “the two whores”.

Pierino was not with them. Tefta sent him to Tirana to Vera, to attend a good school. She wanted to guarantee him a better future than hers. Even Rudina in those years went to school, in the evening, after work, as she did in Savër. He managed to get his high school diploma.

The years in Elbasan were certainly not happy, but Rudina has a pleasant memory there. In 1971, she managed to take part in a paid trip to the sea in Vlora, offered by the regime, for a group of young workers in the garment factory where she was employed.

For a while they had done voluntary work in the hills behind the city of Elbasan: the state needed strong hands to work that bleak land and plant olive trees. Rudina had never seen the sea, and asked an official of the Labor Party (the only party under communism) to add her name to the group, on the condition that the trip would not cause problems. her and she will not force anything on him.

“He dealt with young people and workers and he knew who I was and where I came from, but since I was employed in tailoring, he had a good opinion of me. I managed to convince him”. This is how Rudina discovered the sea. “I sat cross-legged on the beach, watched the waves and cried. I felt a great sense of freedom”.

But Rudina had never really enjoyed freedom, a decent and complete freedom. And that little peace of mind, which had been offered to him until then, at a certain moment stopped. He was fired in 1975. It was the period of the trial and death sentence of Beqir Balluku, Minister of Defense since 1952, accused of conspiracy against Hoxha. In communist Albania, it often happened that internal strife at the top of the system was followed by a wave of large-scale persecution.

That’s what happened that time too. Rudina and Tefta were sent to a camp in Belsh, a locality in the district of Elbasan. And Pierino also arrived there, driven from Tirana with his wife Iqbale, married in previous years and their newborn child: who they called Leone, after the name of Pierino’s father. Later, the couple would have two more children, Ulysses and Anna.

Vera’s family was also affected by the new restrictive measures. The field of Grabiani fell to her, not far from Lushnja. Ali and Vasfia did not leave Savra. Three years later, in 1978, Vasfia died. Rudina thinks about it every day.

“In the morning, when I drink coffee, I see her face. I reflect on the life of a wretch she led in the concentration camps. She found herself with nothing, like the lady she was. She was in great pain, but she kept it inside,” says Rudina.

In Belgium, Rudina worked in an agricultural cooperative. “We had a small salary, but almost nothing could be bought with it. So, one night I went to the cooperative’s fields to steal leeks, tomatoes and spinach”, she recalls with pain.

For nine years she led this life, repeatedly and sadly. The consolation was having Tefta, her favorite sister, for whom she had boundless love.

“She gave the impression of a hard-hearted woman; she was always serious. But if you knew it well, if you understood it from the inside, you could not break away from it. For me, she was my mother, grandmother, brother, father, everything”, says Rudina.

In 1984, a turning point: Rudina was again given a test, this time valid to move throughout the territory of Albania. Only she had that permission, among her relatives. All others remained in camps, effectively until the fall of communism. “Perhaps, since I didn’t have a husband and children, I was a less dangerous Dema for the regime,” she recalls.

Rudina went to live in Tirana. He found work in a textile factory of the “Stalin” Combine, the industrial heart of the capital during communism, today a ruined and forgotten suburb. After three months she met Haxhi Manen, her future husband, five years older than her, also with a painful history behind him.

It is a Cham, as the Albanians of northern Greece call themselves, deported en masse at the end of World War II. Haxhiu’s family was rich. Rudina moved to Durrës, where Haxhiu lived. They got married. She found work in a tailor’s shop; and he as a mason. Megi was born in 1988. Rudina gave birth to Megi at the age of 43.

To her, that little girl was a gift from God: her Christian God. She had been close to Catholicism for a long time. The first encounter with faith was in Tepelena. “There were also some priests in the field, I saw them talking and praying. I was fascinated by them.”

Over the years, her religious sentiment grew. Rudina prayed secretly, because atheism was in power in communist Albania. “When I arrived in Italy, I wanted to be baptized. I did this in 1992, while Haxhiu, who kept his Muslim faith, had no objections,” Rudina recalls.

Even in Durrës, with a family of her own, with the dictator Enver Hoxha, who was no longer of this world (he died in 1985), Rudina continued to be afraid. “I didn’t tell anyone where I was from, I kept a low profile. I felt the weight of my past, of my name, and I believed that the regime could lock me up again in the camps at any moment”.

1990 was a year of turmoil and uncertainty. Various protests broke out. In Tirana in December, students rose up in protests against the regime. The government got out of control of the situation. In the following months, many Albanians took the opportunity to leave: towards Italy, by sea. They did not know if communism would fall. When in doubt, they preferred to travel. Italy, the western dream, freedom.

In early March 1991, thousands of people stormed the port of Durrës and attacked cargo ships moored there. They ordered the commanders to decide to travel to Brindizi, the nearest port of call from which the birds flew, between the two coasts. It was the only way to cross the Adriatic because, at that time, there were no ferries or ships plying that line. The sea was “an impassable wall”, with water.

Between the 6th and 7th of March, 25 thousand Albanians landed in the city of Salento. Rudina and Haxhiu traveled on board the steamer “Tirana”, one of those of the merchant navy. When they saw the mess in the ports of Durrës, they didn’t think too much: they decided to leave.

“I didn’t know what would happen to me, to us, but it was important to get rid of that regime, which I didn’t think could fall. We got dressed. The pilgrim was in a suit and tie, I was wearing a nice suit. We go to Italy, we don’t introduce ourselves as beggars”, we thought.

But together with the refugees we arrived, after a long and tiring journey, in a ship full of people. During the trip, I only thought about my suffering, but I felt free, more or less, like when I saw the sea for the first time in 1971 in Vlora”, remembers Rudina.

In Italy, Haxhiu and Rudina almost immediately received the status of political refugees. They lived for a while in San Michele Salentino, in the Brindisi area, then moved to Antrodoco and from there to nearby Rieti. It is their city since 1991.

Pierino and his family soon joined and then Tefta arrived in 1993, after Pierino’s request to join his mother was accepted. Vera and Aliu, after leaving the camps, instead remained in Albania, both in Tirana. Both they and Tefta passed away: Vera in 2005, Tefta in 2011, Aliu in 2013. Tefta is buried in Rieti.

Haxhiu and Rudina are now retired. In Italy, he continued to be a mason, as in Albania. Meanwhile, Tefta worked as a maid in several houses. She gets a really modest monthly allowance, but she doesn’t complain. “Here I found freedom, friends, the opportunity to say what I think and a social housing. I’ve been through everything, this is enough for me”, says Rudina.

In 2000, Rudina received Italian citizenship and only then wanted to return to Albania. “The Italian passport gave me security; I didn’t have it before. Setting foot in Albania did not excite me. That land had taken everything from me. The only joy I felt was seeing my family again.”

Nowadays, Rudina regularly visits the place where she was born. She has a house in the center of Tirana, but has also been several times in Tepelena, to the former internment camp. I asked her if, after all these years, she feels the urge to forgive — a core tenet of her faith, after all — those who took away her freedom.

“I also discussed it with my priest. He told me that forgiving is a slow process that must be done little by little. But I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to do it. I think it is impossible to forgive everything”. Memorie.al