By Adelina Gina

Part eight

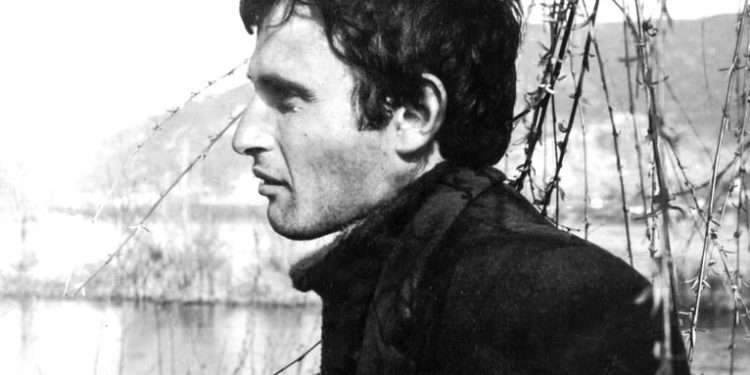

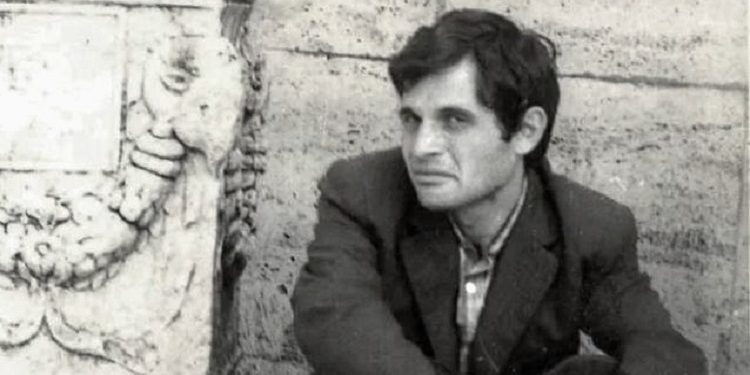

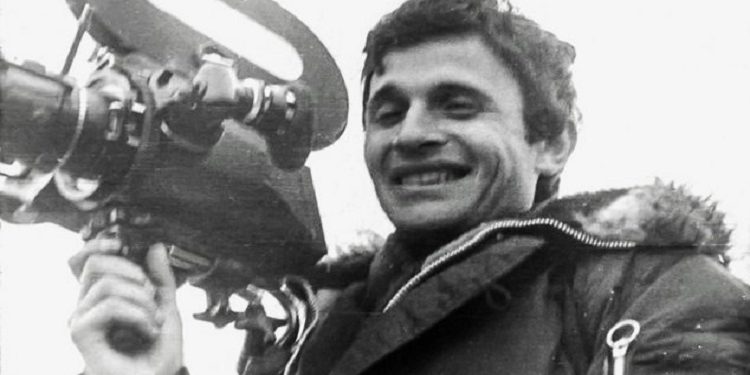

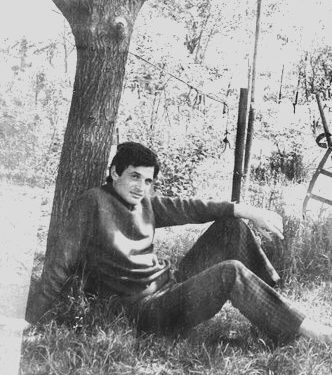

Memorie.al / Rescue Gina, graduated in Journalism at the University of Tirana, in 1974, playwright, screenwriter and librettist, in the early 70s, thanks to his extraordinary talent, his work, works and creativity , “shocked” the artistic institutions of Tirana, such as; The People’s Theatre, the Opera and Ballet Theatre, the High Institute of Arts and the Albanian Radio-Television. He was one of the most sought-after chiefs and senior leaders of these institutions. In the time period 1971-1974, he left his mark, having collaborated closely with some of the most famous names of that time, such as: Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, Pirro Mani, Mario Ashiku, Zhani Ciko, Nikolla Zoraqi and director Mevlan Shanaj and operator Pali Kuke. But the traces he left in these cultural and artistic institutions were unfortunately lost in the official silence of the communist regime?! In August 1974, Shpëtim Gina, lost his life in unexplained circumstances, drowning in two feet of water, in the river Drojë of Mamurras, (where he was performing the military choir together with other students), two days before, he had put a lightning sheet to the Chief of the General Staff of the Army! Was it really an accidental death, or was Shpëtim Gina eliminated by the State Security?! Why his “friend” who was with him until the last moments, declares that; “The body that was taken in the ambulance, wasn’t it Rescue?! Or the doctor of the students’ military ward, Gjergj N., who says: “We immediately went to the scene, but we did not find the body of Shpëti”?! And his family, why insists that; “They didn’t allow us to open the coffin before the burial when they brought it home and years later, we opened the grave in ‘Stalin City’, to bring it to Tirana, where we had moved as a family, those bones were not of Salvation, as they were missing. ..”?! Many questions, which have not yet received an answer! His sister, Adelina Gina graduated in journalism in the late 60s, in a book of hers entitled; ‘Where did you take Salvation’, published in the USA.

Continues from last issue

-“I cried for you like dead, I waited for you like alive”-

It is said that the incident happened at around 12:30 p.m., maybe earlier, but one thing is known, that at that time there was a fire and the students went to extinguish the fire. “When we returned, – his friends told later, we found out what had happened to Shpetimi”. What was this fire? To divert attention from the event?! In my opinion, the fire was planned, some straw bales were burned. I thought this place would shock me; instead, it was helping me solve the puzzle. A well site. Salvation had not traveled an hour, to come to die. They have done something. But what, I still did not have a clear idea?!

I took my mind to all the circumstances; I remembered all the events, the conversations, even the fate of the lady in black. I thought, maybe she did hypnosis and I had spoken and she had gathered from me what she said?! I now guarded my brother, his secret, more than myself. I thought that those who had a hand in this game, if you found out; the first one they would eliminate would be him, my brother. Now that I looked at the water, the land, I could not get used to the idea that Salvation does not live! But what still needs to be done, but which needs to be done carefully?!

“Sister, the soldier addressed me, – it’s good to go, – what do you say?! I heard only that; “Sister” and I came to my senses. Once my brother often called me as a joke “sister”. I hugged the soldier, I leaned my head on his shoulder and wept. “Gone,” he uttered after a while. This word, uttered under other circumstances, would have made me laugh, but at this moment, though inappropriate, for such events, the soldier was shocked, she seemed to warm me. So we had gone through a bad or an illness, but not death. Through tears I smiled at him, shook hands with both of them and we climbed up, the climb was more difficult, the soil it was slippery and the thorns scratched you.

***

It was hot. It was August 15, 1976. Three years passed, the father had requested that we place Salvation on the mother’s grave. One day, from the city where we had the graves, (we now lived in Tirana), came the answer and the date of the opening of the graves. Father’s brother, that war uncle, told father that he would go himself, father refused. “He will do this work himself, it can’t be done with dummies.”

The cemetery is far from the city, there is always a breeze in that part and it is quiet. The mother’s grave is on the side of the road, it is made of red and white marble, and there is her photograph. We have been away for a long time, we go less often, but there are flowers there every day. The caretaker of the cemetery, a simple man, had a mother who was the teacher of his children. “Everyone has passed through her hands,” he says. Every day I put fresh flowers at her grave. “It’s okay that you’re far away,” he says. Yes, I’m here, and so are the people when they pass by they stopped at her.

In the small town, people know each other well. Mother died in 1972, two years after her, in 1974, the death of Salvation occurred. Now he would be placed at his mother’s grave. This funeral was held to reveal the truth. That morning the father sat by the mother’s grave. He loved that woman very much. They never had a fight, and once they did talk, he remembers it. Maybe she sat and remembered how the years flew by, how the children were born and raised with hardships, sacrifices, and then her illness came. For four years, he took great care of her; she was no longer his wife, but his child.

No one who has served a close person can say that he acted like my father, he was exceptional, even I, who had a mother, could not do as he did, and he never showed tiredness or boredom. He, who by nature was a healthy type and who complained about his health, we never heard him complain, that he got tired of serving, fulfilling everything for her. After the death of the mother, when the father went shopping, it was the time of long lines, the women said, “Get out of the line, you are a perfect man. The service you have done to the woman, no one does.” Everywhere among women, the father was honored; women highly value the love of a man. Sitting next to her grave, he seems to gather strength for later: the son’s grave, of Salvation, will be opened.

The gravediggers had started their work. The shocked father was waiting there by the grave. “A rubber glove,” said one of the workers, who was working on the grave, and threw it out. It was one of those that doctors use in operations; another took out some copper buttons and two shoes, one on top of the other. He was buried in military clothes. “They put him barefoot,” thought the father in a flash. He did not want to admit that the man who was there was his son. “She’s shorter than Shpetimi, or so it seems to me. The two front teeth are missing. Shpetimi had them all, and they were like beads”!

They had prepared a smaller coffin and brought it to the mother. The workers felt sorry for this man, who had become the size of a fist, maybe they were surprised that he stayed there in those moments. The father returned to Tirana exhausted, it seemed as if he had languished for a long time. “There was a man there, and an autopsy was done on that man, he said. I’m not sure, maybe it was Salvation?! They killed us”! He used this phrase frequently.

Every day he smoked more cigarettes, he also started drinking a lot of brandy. The father got sick. The doctor said he should give up cigarettes and brandy. He did not know what tormented his soul. “They killed us”! He said. I reasoned: “Yes, it was easier for them to put him in prison. You know how they staged the trials; they don’t need to have facts. If you are on their lists, you go to prison and that’s it. You don’t see how much have they punished in vain, have they created agents everywhere?

Who will stop them? No one. What about his son, did they have a hard time punishing him?! Then he had the name as a modernist and a false witness, these are not difficult to fabricate. You know that for two words, you are punished with the agitation and propaganda article; you yourself told me how they punished that teacher who said that there was no oil in the store, and there really wasn’t. He did five years in prison for just one word!” Father listened to me. “You have to quit smoking”! I told him one day. He thought a little and answered me: “Okay, don’t talk to me for three days, let me fight with myself.” Then he added: “Man has the strength to kill himself”? For three days we didn’t see when he left the room, what he did, when he ate, or didn’t eat at all, and after three days he told us: “Everything is fine. I did it for you.” He did not want us to have a third death. He never smoked again.

***

Six years had passed, when one day I accidentally met the director of my play, Petrit Llanaj. He had been friends with Shpetimi, he had also come to our house. Now I had left artistic circles, artists, I had another direction, education. What they wanted, they achieved. I was left out, without a voice, forgotten. There was no longer talk of Salvation, as a talent, nor of his death, with all the doubts in people’s heads. There was silence! I myself had chosen the path of departure. This event had torn me apart.

Near the “Dinamo” stadium, where I met Petrit, there was a restaurant, where Shpetimin and I went, whenever we ran out of money. She was a charming girl, who had a weakness for her, and we ate “veresie”. She would write down the account in a pad and we would bring her the money when we got our salaries. He met me cordially, I reminded him of Salvation, and there was no doubt about that. Speaking about Shpetim, he told me: “One day, when it came to the theater and I mentioned Shpetim, my brother-in-law jumped up and said that he had recognized him in the choir. I know what I told him: “After you were lucky enough to you are familiar with Salvation. To live as long as you want, that is the greatest thing in your life.”

“Hey, what do you say, I told him well?” What a salvation he was, no, there is no second one”, Petriti continued to speak with superlatives, I interrupted him: “What do they call him”? “Gjergj Ndrenika, I gave him my sister”, continued Petriti. “Where do you work”?, I asked as if without interest. “Before, he was a doctor in Spaçi prison, now he works as a doctor in the Guard of the Republic”. I moved the conversation on to another topic.

I broke up with him after a piece of road. I could tell Petrit that we should go meet him together, but I tried to do all the research without witnesses. That day I went to my father’s house, I was married to Cesar, one of the friends of Salvation. Father was happy to see me, but without sitting down I said: “I found where the doctor works.” In the Salvation bag, where he also had the drama, we found a recipe with the name Gjergji Ndrenika. Then Shpetimi, when I met him in the choir, had told me something about him, so after a while I became interested in finding him. They told me that after the incident he had gone to work as a prison doctor in Spaç. So all the characters were, in a way, isolated. After six years, the one we were looking for appears on the scene. “We’ll go tomorrow at twelve o’clock, both of us. What do you say?” I said to my father. “Definitely,” he said, “this is the main one, he’s hospitalized.”

As soon as you leave the High Institute of Arts, on the right of the road to St. Prokop’s Church, there are some yellow buildings, an iron door, a guard with a gun, there is the Guard. All around, lays a beautiful forest, then the lake, then the Botanical Garden. Nature softens this ward. Greenery, air and birds seem to make it invisible, or rather negligible. How many times have I passed by the lake for a walk, I never thought about these yellow buildings, they seemed insignificant to me, but today, when I was coming with my father, this pile of earth, (there the earth is a little more raised), seemed very important to me.

At the door, we told the soldier on guard that we were looking for Dr. Gjergjin. He announced, and after five minutes, we saw a medium-sized boy, dressed in military uniform, coming towards us. We introduced ourselves to them. It was only a moment; he raised his hat and scratched his head. “We looked for you before, but we didn’t find you,” said the father. “What do you know about Salvation? How did it happen?” “I wasn’t there that day,” he said. “And later, the father asked, that we have asked you”?! “I wasn’t there, because I started working in the prison of Spaci”. “Yes, you were an intern, so you left the choir halfway and got the job appointment”?! “Yes”, he said in a low voice. “You put him in the hospital before the accident happened. What did Salvation have”? “He had a little belly, he was sick,” he said.

I remembered all the words that Salvation had told me that day, that he had laid it in vain, etc., but I could not speak. He spoke through his teeth, he didn’t invite us to sit down, there was a cafe where soldiers came and went. His conversation gave the impression that he knew little about Salvation. His words were this: “I haven’t been, I don’t know anything, I have nothing to tell you.” We shook hands and parted ways.

Father broke the silence first. “You understood why I asked him that question. Even though he was supposed to finish the choir, they take him away and take him, but where?! To Spaçi prison! He won’t talk to you, if you kill him. I know something, but not much”! At the corner of the university, there is a bar. “Let’s go have a coffee,” I said to my father. From its windows, a part of the garden of the Higher

Institute of Arts and the white stairs of the University can be seen. In this building, he studied Salvation and who knows how many other plays he would have written?! Someone had told me, about a dead man of hers, it was a man, it became a word. This was not happening with Salvation, we thought of him as a living being.

Poplar leaves had fallen on the road, October is beautiful. “This is the Faculty of Journalism,” I said. “I know, said the father, he brought me here too. He was strange; he couldn’t stand that desert, as if he would eat him?! And he has those dark writings, you understand? Things must be clear. When he told me, find me a topic? What about when he made the Party, frog”!? Father laughed, I laughed too. I remembered that incident, my father was scandalized then. “Oh, you’re on your own, you make the Party frog”?! “Say, it’s good that you’re softening it,” he said, “I’m just making it ugly,” and he laughed. “I will present it, what is it really like?” “Let’s leave this conversation,” said the father.

After so many years, this event seemed like it happened yesterday. The father had drunk the coffee, he had lost his thoughts. “Let’s go to my place,” I said. I didn’t want to let him go alone, I knew he wanted to talk about it. I always, but especially after the death of my mother and the Salvation, I never spoiled my father. Even when he was not right, I gave him the right. I did it with a conscience. Good with Titi, they told me; “But he has no right”. I answered: “He is always right.”

***

It’s a block with black caps that Salvation had with it. It is a kind of diary, with dates and events given briefly. After the event, Ana asked us, that for the most part, it was talked about. I didn’t give it to him. Before starting the choir, Salvation was in the small town, in the family. From the diary, it appears that Ana also went there to meet him. It says that she goes to the post office from time to time. Shpetimi writes: “As usual, talking with mother, worried.”

What makes you think is the Fourth of July. With a fine print, that he also changed the writing, according to his own style, he writes: “Night. A car following me. I hid in a canal. People looking for me. Dogs barking for me”! You are surprised. It is the time when he is in the choir. This event happened to Shpetimi himself, or is it some fragment from his drama, I don’t know. I’ve read it dozens and dozens of times; I still don’t know how to explain it. This block, together with the drama he had written in the choir, was saved from that day by Madu Marko. When he handed it over to Petrit, his brother, he had said: “When I get out of here, I will speak.” One day, standing at the window of the editorial office, I saw them sitting at the building of a Savings Bank, there on “Durres Street”, Madun. He had finished the chorus. I came down from the third floor and went to meet him.

He smelled of brandy. “After drinking,” I said regretfully. “What else can I do”?! He said and looked at me desperately, with those black eyes of his. “Go home”, I advised him. “They assigned me to Vlora, they removed me from Tirana. I have to work there.” “Will I accompany you?” I asked him. “No, no,” he said, “I’ll go myself. We will talk, – he said, – I will come to meet you at the newspaper.” I shook my head. Madu did not come to meet me. After some time, when I decided to meet him myself, I was told that he had been arrested. He never I found out what he knew what he wanted to say, outside the wires of the military camp?! That day, when I saw him, it was not the time to have such a conversation, I felt sorry for him, as if he were my brother. He seemed desperate. Maybe at that time, they were following him. He wrote poetry and graduated from journalism, along with Shpeti.

Those were the years when, more than ever, artists were arrested. Visari, poet, was arrested; Maksi, Edison, Ali, painters; Minushi, playwright; Mihallaqi, director; Sheriff, singer. And at this time, Salvation also dies. Those were hard times; you didn’t know who you were living with, who was the one who presented himself as a friend?! They continued to create scenarios with enemies and at the same time, hallucinatory party plenums continued!

Albania crawled with the portraits of the leaders, through official holidays. Large portraits, held by the workers, four people to a portrait. All the faces as if cut with a pair of scissors, mediocre, greedy, murderous, even a fox! At dinner, the capital had the leaders on the facades of the buildings, as if they were cinema artists. It was a kind of advertisement with them. Often, from the place where the portrait was placed, one can judge how this or that thread would come.

In the evenings we went out with my husband, he had an intuition for this work. “Do you see where they put Kadri Hazbi”?! He said to me one night. It had rained a little, the portrait was wet. Kadri had less light than the others. With that long nose and eyes like a fox, in that half wet darkness, it seemed that they were preparing to take him somewhere. It wasn’t long before he was declared an agent. And when a wall was erected around the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Cesari said: “They’ve got him now. This wall is a bad omen”! It is said that works were done there. How do they know what they are doing? Only one thing is known, that all their jobs are black. Every time I passed by, I cursed to myself: “You’re upside down, oh god!” They had terrorized a whole people, even the party rulers were afraid of them.

Caesar is perhaps one of the rare cases, who opposed them. In the 70s, he was called by the deputy director of the State Security, S. Backa, the author of the false trials developed in those years, where innocent people were convicted. Backa (we called him “Cologne” among us, because he was smeared with spices and powdered) asked to recruit him. “We teach you how to provoke,” he told her. “Become a spy”?!, said Caesar. “Never”! Backa’s red eyes flared up: “What about us”?!

He instructed him that he would be punished by law if he spoke about this proposal and the case seemed to be closed. After a few years, Backa got his revenge. Cezar went from being the head of the department, at the University of Tirana, to working in the Kurbnesh mine. For ten years in a row, the right to publish was taken away. They are also terrible in their revenge. It’s hard to resist them. Often with a laugh, he tells me: “You married me because you wanted to challenge the State Security”! Memorie.al

The next issue follows