By Josef Jakoel

Second part

-ISRAELITS IN ALBANIA, FROM THE 19TH CENTURY, UNTIL THE THRESHOLD OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR-

Memorie.al / About the Israelis in Albania, there is little information about the period of time that extends from the beginning of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century. Isolated Israelis have come to Albania, but they have not taken root nor formed stable communities. In the “Avlona” entry of the Eshkol encyclopedia (Berlin 1929) it is said that Ali Pasha Tepelena, the Albanian ruler of Ioannina, had many Israelis in his council, but still the economic condition of the Israelis was low. Because of his persecutions, many Israelis escaped from Janina and settled in Avlona (Vlora), but Ali Pasha extended his power over Avlona as well. After this tyrant ruler was executed in 1822, these Israelis returned to Ioannina.) Professor Fejzi Hoxha writes that since 1839, an Austrian doctor, Doctor Auerbach, settled in Albania, who practiced medicine in Vlora, in in 1867, as a quarantine doctor. Later he went to Gjirokastra, where he worked until around 1881-1882.)

Continues from last issue

-Chronicle of arrivals and the formation of communities-

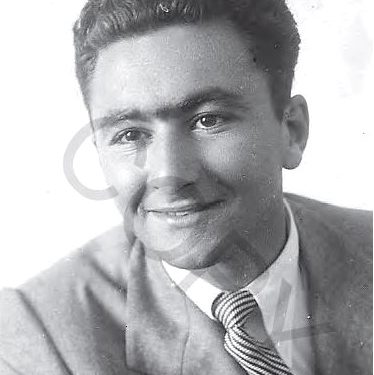

In 1935, tailor Samuel Haim came from Corfu, Greece and settled in Kavaje, together with his wife and five daughters. The whole family left for Israel in 1947. In addition to these, there were also lonely Israelis in Albania who had come temporarily for work reasons. Such were; David Tiano from Thessaloniki, who left after the liberation, and Edmond Ersekovic, originally from Hungary, who died in Tirana and was buried in a corner of the city’s Muslim cemetery, given to Israelis by the Albanian Muslim Community. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler took power in Germany. Since that day, the odyssey of German Israelis and those of other countries occupied before the war by the German army (Austria, Czechoslovakia, etc.) began. In the first phase of the persecution, the Israelites were expelled from these places and wandered wherever they could. The year 1933 is considered the year in which the fifth return (Aliyah) of the Israelites to Palestine began. At this time, the arrival of persecuted Israelis began in Albania.

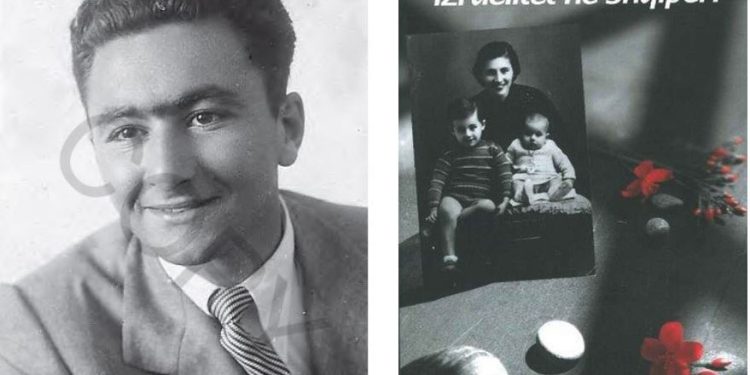

Most of them passed through here to find the opportunity to follow the road to other countries, mainly in South America, the USA, Turkey, etc. Among them, there have also been personalities in various fields of human knowledge, such as; Dr. Meyer (Meyer), an eminent gynecologist, Dr. Blumenfeld, a surgeon, and then a number of other people. For the latter, Isak Koheni in Durrës, Rafael Jakoel from Vlora, etc., provided great help. These provided them with housing, gave them opportunities to earn their living and, when they did not have these opportunities, helped them with money and then provided them with conditions to continue their journey. In those years, dozens and dozens of immigrants passed through Durrës, but very few of them stayed in Albania. One of these was Leo Tyri (Thür, or Thuer), a man with a strong personality, who stayed in Albania until 1945. He played an important role in the rescue of local and incoming Israelis. Among the families that eventually stayed in Albania, was Avram

Shvarc’s family, whose descendants, Roberti, a prominent translator, lived in Tirana with his family, while Renata, an otolaryngologist, eventually returned to Israel.

In 1932, the new Military Hospital of Tirana was opened, with director Dr. Hiqmet Gega. Dr. Eugen Levi, an Israeli of Bulgarian origin, also served as a doctor in this hospital. In 1936, Professor Walter Lehman, an Israeli-German, frightened by the persecutions of Nazism, fled his country and became a surgeon at the hospital in Vlora, but after eight months, with the departure of Professor Hoche from Albania, he was called to replace him. him as chief of surgery at Tirana Hospital. (With the occupation of Albania by Fascist Italy, he left for the USA. Dr. Lehman is considered the founder of the branch of neurosurgery in Albania. The neurosurgery department at the “Mother Teresa” Hospital in Tirana today bears his name). Finally, even though he had come during the Second World War, he finally settled in Tirana, Marko Menahem, who came from the Macedonian city of Skopje, where he had lost his entire family, consisting of his parents and a sister, all exterminated during the holocaust. Marko lived in Tirana, together with his family, consisting of his wife and three married daughters, who are all in Israel today.

* * *

As it is clear from what was presented above, the Israelis who came to Albania, starting from the first half of the 19th century, are of origin from different countries in Europe, but most of them, (that part which became the basis for the creation of the small community of Vlora), came from Janina and Preveza. There are erroneous opinions that the Israeli communities of Preveza, Arta, Ioannina and Vlora originate from Spain, as a result of the persecution developed there by the Spanish Inquisition. Actually, coming from Spain at the time of Sultan Bayezit II, they were the Israelis who settled in several cities of Greece, mainly in Thessaloniki, from where they gradually spread in different directions, such as in Yugoslavia, and also in Kosovo, as well as in other Greek cities.

Likewise, the Israeli communities that were formed from the end of the 15th century in Vlora and then in Berat and Elbasan originated from Spain. These were discussed at length in the first chapter.

These Israelites have always spoken a Catalan dialect of the Spanish language, and continued to do so until the time they disappeared as a community. The same thing happened in those cities of Yugoslavia where there were Israelis, such as in Bitola (Bitolje), in Skopje, further north, such as in Belgrade, up to the northern borders of the country, in Novi Sad, etc. Even the Israelis of Kosovo spoke Spanish at home. But there, from the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, the Israeli communities of Vlora, Berat and Elbasan, who came from Spain, disappeared, either by leaving Albania, or by embracing the Islamic religion somewhere in the country and somewhere the orthodox religion. The communities of Kosovo remained and their Israelis spoke Spanish until they were dissolved after the Second World War. The third wave of Israelis who settled in Albania, starting in the middle of the 19th century, came mainly from Ioannina and Preveza, where the Israelis existed long before the arrival of the Sephardim. The first Israelites who came to Greece settled there in the second century BC. It is not known precisely when they settled in Ioannina and Preveza, but it is nevertheless documented that the Israelites have been there since at least the 1st century AD. These Israelis of Ioannina, and some other cities, such as Preveza and Arta, are “Romanians”, a word derived from the Venetian name for Greece, Romania. The Romanians are not descendants of the Sephardim.

They had settled on Greek soil centuries before the arrival of immigrants from Spain, Portugal and the provinces of Italy (Puglia, Sicily and Sardinia). As mentioned, they have been influenced by Greek culture, they speak the Greek language and until the 16th century, they used as a prayer book, the Mahzor Bene Romania, compiled several centuries before the immigration from Spain.

The Romanians are considered one of the most ancient Israeli communities and virtually unknown in other parts of the world. It is likely that the Romanian community was first settled in Thessaloniki, around 140 BC. Another famous traveler, the Arab Abu Abd Allah Muhammad al Idrisi, born in Ceuta (1099, died in 1165?), testifies to their presence in the regions of today’s Greece. He mentions the community of Ioannina as the community of a city built on water, and indeed two-thirds of the city of Ioannina is surrounded by the waters of the lake of the same name. Even the Jews of the community of Ioannina, to distinguish them from the city, say that it is a “ghiod” city, that is, built on water. Likewise, the Spanish Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, mentioned above, passed through these areas in 1170 and visited many Greek-speaking Israelite communities. He writes that in these territories, there are 28 Romanian communities. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were about 4,000 Israelis living in Ioannina, most of whom were engaged in small trades, craftsmen or clerks, and lived in two neighborhoods inside and outside the walls of the old city. The ancient synagogue of Ioannina, which was built within the walls of the old city, was called “i mesini”, or “inner”, to distinguish it from the synagogue “i oxini”, or “outer”, which was on the street main.

It should be added that the Romaniote Jews of Ioannina and Preveza were influenced by Greek culture and customs, spoke the Greek language, but at the same time preserved their identity as Jews, practicing their religion and traditions of life. As we mentioned, the Israelis who came from Spain spoke Spanish. But in Corfu, there was a large Israeli community, which came from Venice and settled in that city, around the middle of the 14th century. For this reason, until its complete destruction, in 1944, the Israelis of Corfu spoke the Venetian dialect of Italian. The fact that the Israelites of northwestern Greece, southeastern Greece, and the Peloponnese spoke the Greek language in itself is a strong argument that the Israelites of those countries settled in those regions centuries ago.

When the Spanish Israeli immigrants came to Ioannina, they were separated from their Romani co-religionists. The Sephardim did not present themselves as a solidary community, but were divided into small groups, where each kept their own customs, brought from the countries from which they had emigrated. Despite the very large number of Sephardic Jews, who arrived later, the Romaniots did not merge with them and continued to preserve their special characteristics, both in religious rites, melodies of songs and prayers, as well as in language and daily life. . (Although they read the same books of the Torah in Hebrew in the synagogues, the rites, melodies and language spoken in the family distinguished the two communities between them. Thanks to this centuries-old stability, the Romaniotes were not assimilated into the Christian religion of the majority of the Greek population and nor did they embrace the “Ladino” language, or the liturgy of newly arrived Sephardim co-religionists).

In the early times of coexistence between Romaniotes and Sephardim, there were strong rivalries. But over time, they gradually found their way to agreement. In some cases, when they prayed together, among the religious rites, those of the Sephardic Israelis began to dominate, because it was difficult to acquire the rites according to the “mahzor Romania” used by the Romanians. At first, marriages between Romaniotes and Sephardim were not accepted, but slowly things changed. Yaninyot Israeli women found it easier to acquire the language and customs of their Spanish-speaking husbands; men found it difficult to learn the Greek language of women. But, fortunately, in their rites the Israelites of Ioannina preserved their own melodies in the Greek language. They also preserved their customs, which over the centuries, in contact with the Greek environment, were influenced by this environment. These factors caused the Romanian Israelites of Ioannina to become a special type of Israelites, known by the name; “Ianjotics”, speakers of the Greek language.

In 1912, the city of Ioannina and its districts passed from Turkish rule to the rule of the Kingdom of Greece. On that occasion, the heir to the Greek throne, Constantine, who at the same time held the office of commander of the troops that occupied the city, in order to reassure the Israelites worried about the arrival of the Greeks and their further behavior towards them, visited with ceremony and great uproar, the synagogue of the city and there he gave a speech where, among other things, he thanked the Israelites who had preserved the Greek language through the centuries with admirable persistence and purity. On the eve of the Second World War, there were still four Romanian communities in Greece: in Chalkida, Arta, Patras and Ioannina. The Israeli community of Ioannina, before the Holocaust, was the largest Romaniote community in Greece and one of the leading Israeli centers in the East. The Romanian traditions of Ioannina continue to be applied outside of Greece.

In the USA, it is the synagogue of the Romaniot rite in Manhattan, New York, while in Israel, it is located in the Nachlaot neighborhood of Jerusalem. In a sense, the Synagogue of Ioannina was considered the metropolis of these Romanian synagogues, and the one in Manhattan bears the same name as the Synagogue of Ioannina: Kehilka Kedosha Janina (Holy Community of Ioannina).

From the above, it appears that even the Israelis of Albania, who came last time, i.e., in the 19th century, mainly from Ioannina, have no connection with Spain and their first language was Greek.

Environment, life and religious rites of Israelis in Albania

At the time the Israelis started coming to Albania, the country was under Ottoman rule. In those centers where they were first settled, the majority of the population was Muslim, a minority was Orthodox (in the south) and Catholic (in the north). Even before they settled in the lands of today’s Albania, the Israelis who came from Ioannina and Preveza had frequent relations with the Albanians, firstly because Ioannina was for years under the rule of the Albanian Ali Pasha Tepelena, Pasha of Ioannina, man the valuable and wise state, surrounded by its loyal Albanians, therefore the Albanian language was also spoken in Ioannina. Secondly, in the districts of Ioannina and Preveza there was a large Albanian population, both Muslims such as the Chams, inhabitants of Chameria, and Christians, such as the Suliots, the brave inhabitants of Suli, who had Albanian as their mother tongue. And there were not rare cases when Israelis, especially those from Ioannina, lived in the towns of Chameria, with or without their families, and exercised their profession there, mainly as commissioners. So, when they came to the lands of today’s Albania in the 19th century, the Israelis did not fall into an unknown environment, they even had friends and acquaintances. This made their lives much easier.

In the Greek language spoken by the Israelis of Ioannina, some Albanian words had taken their place. So for example; the word Albanian was widely used; “cucumber”. Likewise, nicknames derived from the Albanian language were used, such as the name “Tepelenis”. During the time of Ottoman rule, some Israeli children were called Biros. “Bir” is the Albanian word, while the suffix “-o” is a pet. In the years of the Israelis’ stay in Albania, some proper Israeli names have acquired Albanian forms. Such are the names Minush (for Menahem), Ilir for Ilia, and others. The provinces of Gjirokastra, Delvina and Vlora, where the Israelis first settled, were included in the Sanjak of Ioannina. There were cases when young men from these provinces performed military service in Ioannina. Therefore, some of these were friendly with the local Israelis, thus strengthening mutual relations.

The Israelis who came to Albania at that time were mainly engaged in trade, and there were very few cases when they first practiced any trade, such as carpenters or tinsmiths. They were people who had fled their countries, to earn a living and lead a better life, therefore they did not hesitate to go to sell or work, even in the deepest areas of the provinces. This made them befriend the Katundars of those regions, who are people who, when they swear allegiance, call them friends. These visits were so frequent that there was a case, such as that of the Israeli Isak (Cako) Matathia, who died in Tragjas village, located south of Vlora. At first, he was buried there and his grave became a reference place for meetings. We used to call it “The Grave of Cako” or “The Grave of the Israelite”.

Even when his remains were brought to the Israeli cemetery of Vlora, that place continued to be called and is still called today; “Tomb of Cako”.

Israelis who moved from Gjirokastra and Vlora to Durrës and Tirana, as well as those who went there directly from their place of origin, were later welcomed with friendly feelings. With the exception of some fanatics, the Israelites were respected as honest, hardworking people who do not know how to harm anyone. The relationships were not only limited to the work field, but also extended to the family world. When the Israelis established close relations with the Albanians, they managed to become brothers with Albanian boys, which means to become a brother with him, this custom that enjoys great honor among the people. Likewise, in Vlora it happened that a mother with a newborn child would give the baby to her Israeli friend and vice versa, when the mother did not have milk, to feed her own baby. In the last decades of the 19th century in Albania, a great cultural and political movement began, which aimed to achieve the country’s liberation from the Ottoman rule. This movement is known as; “Albanian Renaissance”. The revivalists aimed to nurture in the people, a great national feeling and awareness of the antiquity of the nation, language and traditions, in deepening the feeling of brotherhood between Albanians of different faiths, to cut off those hostile forces that through religion, they tried to divide the Albanian people.

“Albanian’s religion is Albanian”, poets and patriots of that time wrote. This national movement, which culminated in the rebirth of Albania, the language and the desire for independence, benefited the Israelis. As brotherhood was preached between the main religions of the country, this reflexively extended to relations with the Israelites. In such circumstances, when the Albanians called the Jews equal, without a shadow of contempt, persecution or humiliation, it is not surprising that since the first generation of people born in Albania, the Israelis jumped without hesitation, alongside their Albanian brothers, not only in the Independence movement but, whenever, up to the struggle to liberate the country from Nazi-fascist occupiers. At the threshold of independence, it was not uncommon for Israeli mothers to rock their children, singing them Albanian patriotic songs. Although on November 28, 1912, the national flag was raised in Vlora and Independence was proclaimed, Albania did not find peace at all, because different enemies sought to drown it from the cradle. The Israelis joined the Albanian people, and even made a good contribution in some cases. Thus, during the Vlora War, in 1920, the Israeli Josef Mushon Kantozi, who was in Italy at that time, killed an Italian lieutenant, who dared to insult the Albanian people and his homeland.

This same Israeli, for some time performed the duty of Police Commissioner in Vlora and then it was said that he would be sent as the Consul of Albania in the Italian city of Bari. Years later, in the 1930s, the country’s constitution stipulated that only Muslims and Orthodox should be elected as city councilors in proportion – in Vlora – two to one. However, in the elections that took place in the early 1930s, Samuel Josef Matathia, also this first-generation Israeli born in Albania, was elected municipal councilor. At the time of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War, from among the Israelis of Albania, there was a martyr, Dario Jak Arditi. Since January 1943, Pepo Kantozi has been a participant in the war and in August 1944, he became a partisan in the Third Group of Mallakastra. At the end of the War, he remained in the army and filled important posts, attaining the rank of major officer. Under the influence of public opinion, even occasional governments have maintained a favorable and very correct attitude towards the Israeli community of Albania. This community had its own cemetery in Vlora, which it inherited from the Israelis who lived in Vlora from the end of the 15th century until the end of the 17th century. The cemetery in question was used for the first deaths of some Israelis, at the beginning of the 20th century.

However, from 1933, the owner of the olive groves that were close to the Israeli cemeteries, claimed that those lands were his and demanded that the cemeteries be removed from there. Without hesitation, the Israelis took the case to court, proving that the cemetery in question had belonged to the Israelis for three centuries.

The main evidence for this was that, while digging a trench to use as the border of this cemetery, the workers came across an Israeli grave, belonging to past centuries. As a result, the court of Vlora rejected the plaintiff’s request and the cemetery remained for the Israelis to use until 1965. In this year, for urban planning reasons, all the cemeteries of the city of Vlora were moved to the vicinity of the village of Babicë. where they are even today. The small and ancient cemetery was abandoned, and today it is almost lost. In the 30s, a local newspaper published in Vlora, for the personal purposes of its publisher, wrote an article, which stated that; the market of Vlora was ugly on Saturdays, because the shops of Israeli traders were closed. The article writer claimed that his day off was Sunday, therefore it was not allowed for anyone to act on their own and break this legal order. Influenced by this article, the Municipality of Vlora ordered the Israelis to open their shops on Saturdays, otherwise, it would be forced to punish them first with a fine and later, in case of repetition, with other punitive measures . On the first Saturday after this warning, Israeli shops began to close and the Municipality fined their owners. On the second Saturday, the fine increased and some Israelis were unable to afford it.

Therefore, the community decided that those who were unable to afford the fine should open their shops, but not carry out any sale and purchase. When someone asked to buy something, they received as an answer that the goods were not available. Others, to keep the shops closed, to show that the action was not against the law. This situation continued for several weeks, until the court where the case was presented by the Israelis for judgment, decided that, according to the Constitution, everyone had the right to respect the commandments of his religion, that is, to keep the shop closed even on Sunday, that it was the appointed day of rest, for the whole market. Based on this decision, the municipality not only did not impose other fines, but was also forced to return the ones it had imposed until then. There was not even the slightest racial prejudice in Albania. Young Israelis at the age set by the law were recruited as soldiers and could attend a military training school, from where they graduated with the rank of officer of the Albanian army. (This fact is confirmed by the American ambassador to Albania, during the years ’30-’33, Herman Berstein, who pointed out in his writings, the complete absence of anti-Semitism in Albania). Whoever wanted to find a bride abroad could bring her to Albania to marry her. And conversely, girls who wanted to marry abroad had no obstacles to do so. This was an opportunity that strongly helped to preserve the identity of the community. Memorie.al

The next issue follows