By Petraq Xhaçka

The sixth part

Memorie.al / The purpose of this book is to join the efforts made to present the truths and horrors of the communist dictatorship in Albania. The main purpose of the book is not to show our people or anyone else that we oilmen have been innocent, because this has become known from publications in our press, from foreign televisions, as well as from direct meetings with the International Forum and the Albanian Human Rights. The author’s desire, is that through this story, along with other stories, fight any manifestation in any form, even moderate, that he may have to create a communist society. I think that even through this bitter personal history, the cruel, treacherous and overbearing face of Enverism will appear, that for half a century, held the knife with the tip in the chest of the Albanian people, with a pine eye, intercepting the movements for salvation from the outside, or rebellion of the people themselves, ready to push the knife to the heart, at the first movement. The events are set in the economic fields where it has appeared most strongly, such as the oil and gas industry, where I was fortunate to pour my energies, for a lifetime, and become a participant and witness in those events. All the events that are written in this memoir are true, not only without any exaggeration or embellishment of them, but perhaps, I don’t know how much I have been able to present the terrifying force of the events that took place in that decadent system of socialism, where there was no no human feeling.

I fondly remember the times when Ramadan Hoxha and I used to ride the bus or subway. I was known to be better off financially, but he did the habit: he would put his hand in his pocket and say:

– Oh, look, only five kopecks, there’s Uncle Dania! If I had you, I’d pay for both, but here. You pay us the tickets, now!

Of course, I paid with a laugh. Whereas Dhimitri, in the dormitory canteen, used a more indirect language.

– You Peçi, – you tell me, – stand in line here at the cash register, where the coupons are paid and taken, while I am holding the line where the dishes are taken, so that we are not late. And so we did.

The Albanian group of the institute was distinguished as a whole for seriousness in studies and correctness in the field of social relations, in respect of all disciplinary rules. We did not have a single student who remained, who repeated the class or became the object of any unpleasant event, to return him to his homeland, as happened at Tuk, with students in other schools.

Some of our comrades married Soviet girls. But there were many others who were convinced to give up such an enterprise. Most of us considered marriages of this type troublesome for our conditions.

The truth is that Soviet students and people were closer to us Albanians. Apparently, this was because we were more readable, more sociable and more open, as we were with all students from other countries. When we bought things in stores, or when we opened packages of drinks and foods typical of our country in the dorms, we shared them without much ceremony with our roommates. Russian students did the same thing.

I cannot say this about students from other countries, for example Czech, or let’s say, Polish. Let’s not talk about the Chinese students. Those poor people, even though they didn’t like it, still more blindly followed the rules set by their communist leadership: they dressed alike, went out on the street together in a line, didn’t drink any kind of alcohol, in their evenings, or at school, being presented that they had no appetite, that’s why they didn’t put it in their mouths.

But, in fact, many of them drank, and when they were lucky enough to live in rooms with Russian students, some of them drank more openly and begged the locals not to reveal their secrets. So in the evenings, we waited for the New Year. While all of us students from European countries gathered in the narrow social evenings, the Chinese girls gathered in the open halls of the dormitory. Their party lasted only half an hour. No other drinks, except lemonades. There was no question of dancing at all.

Soviet students, and the youth of that country in general, did not give a damn about political problems. They showed certain apathy in this direction, so much so that many of them did not know the main leaders of their party and state, which no one could imagine, encountering us, the students of the shores of the Adriatic. Locals did not read the political press, while the meetings of the Komsomol organization were rare and almost formal. Some students were attracted to the world of sports.

We had an intelligent and sports-loving boy in the class, Eduart Roshkov, who had a lot of company with us Albanians. He knew them and knew how to talk about the well-known Albanian football teams, about Shkodër or Vlora. But they were mainly attracted by the literature of Russian and Western giants, whose works were translated into serial columns or separate volumes.

I have had the opportunity to visit many countries of the world, but it has not caught my eye to see people reading as much as in Russia. There they didn’t share the book on the train, on the tram, on the bus, in different queues for tickets and everywhere, and not only in sunny summer days, but also in the cold Russian winter days, except when they were standing in line, to wait for the bus.

The conversations that opened with them were mainly about books, about what had been read that week or that month and what was to be read in the days to come. In such an environment, I began to read a lot of popular Russian literature by Tolstoy, Gorky, Lermontov, and Pushkin. I read Esenin, especially his lyrical poems, unpublished, but circulating secretly.

I was drawn to the sought-after Western literature, such as that of Dickens, Hugo, Maupassant, Jack London and others. When I then returned to my homeland, I brought with me many serial publications of artistic literature, as well as albums of distinguished painters. The paintings of Great Russian and world painters filled the museums of fine arts in Moscow and Petersburg, which I visited so often, were truly unique.

The visit to the open exhibition in Moscow, with the works of the German museums, taken by the Soviet army as war trophies and returned to the German side after the exhibition left an indelible impression on me.

In those years in Moscow, books by western modernist authors or by Russian dissident writers were secretly circulated, which were not allowed, because they, with their special language, called for the crimes of the communist system in Russia to be condemned. Acquaintances would give me these strictly forbidden books and beg me to read them overnight, or many in forty-eight hours. They had to surrender immediately, because dozens and dozens of others were waiting for their turn.

Among the Soviet youth, rock music began to spread secretly, which was very much liked by everyone. It spread gradually, in narrow circles at first and then little by little in the evenings and in bars. Modern literature, films, acquaintance with the high results of capitalism in the economic field, rock music, which I began to enjoy and then become a great amateur, phenomenal results in sports, as well as the opinion of many young people, about the Western Hemisphere, they made me have a broader and fairer idea of true democracy in the world, especially in the United States of America.

As a result, step by step, I began to look more realistically at the social system of these countries, and consequently to open my eyes relieved from the indoctrination that had sickened the social life in Albania. Life in our homeland was miserable, we were forced to accept it that way, because we saw it as completely impossible for anyone or people to change it.

The frozen mold in my mind, on the supremacy of the communist system in Russia, in Albania and elsewhere, began to melt, and years later, seeing in my country many wild and unacceptable manifestations of the communist dictatorship, it melted almost completely. . The great disappointment gradually gave way to a deep, great, hidden hatred.

When we were in our country, before we came to Moscow, the press and the propaganda materials of the party urged us to take an example from the life and work of the young Soviets or Komsomolas, as they called themselves. Thus, in our imagination, the characteristics of the Komsomol, and the virtues of Komsomol members, came and occupied a completely idealized place. When we started the lessons, we noticed that there were Komsomol members who did not study well and when they entered the exams, they made a copy, which we would never have believed.

Although this is normal for every school in the world, this fact impressed us, as if the gods had fallen to the ground. So our propaganda, there in Tirana, had lied to us like pigs. One day, when we were taking the written math exam, I saw on the last bench, a young man, whom I had never seen before, in our class.

When the exam was over, I asked my roommate about it. He answered me that that boy had appeared instead of another Russian student we had in our group. And, to our surprise, this happened; no one went to report it to the deans, or to the Komsomol.

Often times, our classmates, roommates or others openly told anecdotes about the leaders of their party and state and, especially, about Khrushchev, especially after his visit to America, but we never noticed a case, for someone to report and take a stand on this. If you did such a thing in Albania, the savage dictatorship would immediately put you in prison, as a minimum, for ten years.

I remember when Khrushchev went to America and came back, he brought out the thesis on economic development that: “We, the Soviet Union, will reach and surpass America” and immediately we heard the anecdote: – We will only reach it! To overcome it, we will not overcome it, because they see us behind, bare ass!

In addition to the lessons, the translation work I was doing and that of the compatriot student organization, I also had a great passion for sports, and therefore from the first year, I decided to learn ice skating and skiing. After I bought the skates, I went for the first time to the “Gorki” Park, to the special place, which was for beginners, where, of course, it is understood that I found almost only small children.

When they looked at me, who was held on some parallel bars, walking with great difficulty and not slipping, they approached me and said: “Hey, uncle! You’re so big and you don’t know how to slide?!” I laughed with these kids and with perseverance, for a short period, I mastered the skates and somewhat the skis quite well.

I felt a great pleasure when I came to these squares. We also had a small square in the courtyard of our dormitory. During the winter it became ice and we prepared it for sliding. Almost every night, after finishing my studies in the late hours around midnight, I would go there for half an hour, get some fresh air and refresh my brain, which was overtired during the day.

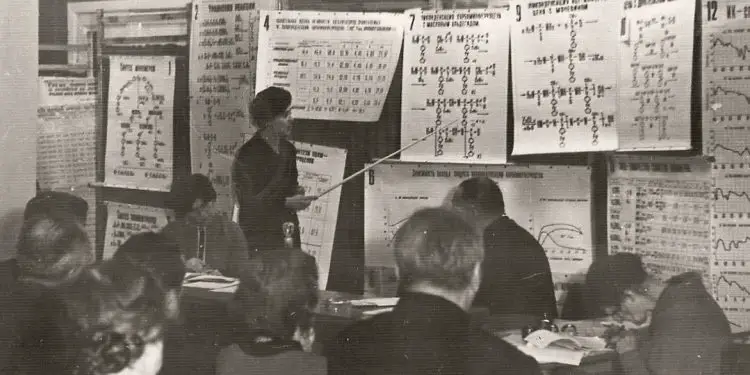

In the last two years of our studies, he came to us for a few months, Ing. Teki Biçoku, who in 1951, graduated from our institute, the branch of Geophysics. Now he had come to prepare and defend his dissertation for

Candidate of Seismic Sciences.

At that time, he worked as Chief Geologist of the Albanian Geological Committee in Tirana. Settled in my room. During this time and the later period, I noticed that he was a very calm man, measured in his thoughts and quite communicative with specialists. Later, I had the opportunity to work closely with him, because he was assigned the task of director of the Geological Directorate in the Ministry, for oil and mining.

At that time, I would never have thought that this specialist, former partisan, who spoke so passionately about the development of geology in our country, years later, would end up as an “enemy of the people”. Just as I could not imagine that I, too, would have the same bad conclusion that all those beautiful and pure dreams of our youth, to remain honored in the history of our people, would one day come from the dictatorship communists would become ashes.

In such an environment filled with studies, displays of friendship and relaxation, months and years passed, without mixing at all in conversations or political actions with foreigners. We had only one preoccupation: to learn well, to turn out to be good engineers, and to justify the opportunity that the state gave us by sending us with a scholarship to study abroad, for which I was very grateful.

Precisely and that is why I was active and tried to perform well the social duties I had, in the patriotic organization of students. And life showed that we, the students of the “Gubkin” Institute, performed our patriotic duty with honor and in our personal interest, which we had before the state and our families. Not a single event or shameful act, by any of us, was carried out during all those years, because the relations between our states and peoples were very close.

In 1959, I finished my studies as a geologist at the Oil Institute “Gubkin” in Moscow and returned to my homeland. Since I graduated with an excellent degree, the nomenclature bodies had predestined me to work as a lecturer at the University of Tirana.

The General Director of Nafta, Ramiz Xhabia, came to Tirana and was interested in meeting me. As soon as he found me, he immediately told me that he had come to ask me to leave teaching, to leave the University, and to return to the oil industry.

– Come to us, – he told me warmly. – You are familiar with the oil sector. You worked on it since you were young. I’m sure again, you’ll do a great job there!

He convinced me. I gave my consent. Xhabia submitted the request for me up in the center and thus eventually I was appointed chief geologist of the Marine Oil Company. Along the way of life, we often have to make decisions.

But not all decisions are important. Some of them, however, are fatal. Your whole life that of your people, relatives, then has as a heavy weight, that decision for which, over the years, you say hundreds of times: “I shouldn’t have accepted it! I shouldn’t have accepted it”!

That summer day in 1950, with Xhabina, I should not have made that decision. “I shouldn’t have agreed to deal directly with the oil field!” I was muttering as if in that dungeon of the Department of Internal Affairs of Fier, as a new, icy March day dawned and the thunder penetrated through the glassless window… Memorie.al