By Prof. Asst. Dr. Thanas L. GJIKA

-Evaluations for the work “PIKA LOTI” by Sami Repishti-

Memorie.al / Sami Repishti, together with Martin Camaj and Arshi Pipa, is part of the trio of great dissidents from Shkodra. This three-thousand-year-old son of Shkodra, former anti-fascist and former anti-communist, former prisoner and exile, after escaping from Albania, found himself in the USA, where he managed to become a literature teacher, with the title of Assistant Professor. He is a complete personality of the Albanian-American pedagogue, researcher, writer and politician. He is a multidimensional figure of Albanian and American culture, literature, science and patriotic political activity. When studying his life and his complete work, it will be seen that he with many articles, essays, literary works, in terms of anti-communist dissident content, maturity and high humanism, they remind Vaclav Havel (1936-2011) and Karl Popper (1902-1994).

Unfortunately for us, this persecuted person, this prominent personality, when he came to his homeland after the collapse of the dictatorship, to help the progress of the processes, was not listened to as much and as it should have been by the “democratic” government, for the punishment of the communist crime, for the return of the property to its owner, for the development of the political game between the position and the opposition, as a fair democratic game, without dividing the people into two hostile halves, etc.

Sami Repishti was not heard because he was part of those social forces that constituted the real opposition against communism. Such forces were predetermined by Ramiz Ali’s plan, not to be involved in the transition processes, and not to direct them. Pluralist Albania with a market economy should have been built and inherited by the loyal sons and servants of the former communist dome, most of whom continue to rule it even today…!

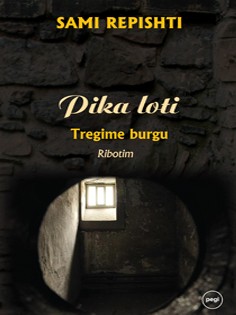

I regret that the two literary works ‘PIKA LOTI’ (1997 and 2009) and ‘IN THE SHADOW OF ROZAF’ (2004) by Mr. Repishti, I only read these in the last few weeks, i.e. late from their publication. These two works are part of Albanian realist literature, and more specifically, they constitute the foundations of our literature called ‘prison literature’, which is read today with pleasure and great benefit, because it reveals the life full of suffering, endurance and deeds of people convicted by the Albanian communist dictatorship, an aspect of our life, which the dictatorship had badly distorted and kept in secret.

Albanian realist literature created in the first decades of the 20th century, by Andon Z. Çajupi, Zef Skiroi, Gjergj Fishta, Ernest Koliqi, Faik Konica, Migjeni, Nonda Bulke, etc., etc., during the difficult years of the communist dictatorship (1944-1991) fell into disrepair, but did not stop. It fell into disrepair, because the communist dictatorial power stimulated in those years the literature called “Literature of Socialist Realism”, whose works were drawn up according to the requirements formulated by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and the rules devised by the Soviet theorist A. Zhdanov. This literature took upon itself the task of serving the communist parties in power, for the creation of a new order, through the creation of a positive hero. This hero was embodied in the figure of a communist, a common man, or a party secretary.

This literature in China created a hero like Laj Feni, in Albania it created the hero of ‘Stavri Lara’ (the novel Swamp by Fatmir Djata) and many others…! This type of literature, which was so stimulated by the party state, only brought damage to the art and psychology of the society of the country where it was created. To their shame, the authors of such acts have not apologized to the people for the damage they caused, but continue to brag about them. The works written according to the principles of socialist realism, today no longer attract us, they are read with difficulty and with a feeling of disgust, because they glorify politics and morality that only served the rule of the state party.

After 1944, not all Albanian creators abandoned realistic literature. Only a few Albanian writers, who ended up in prisons and labor camps, and some of the fugitives in the free world continued to praise him. In honor of Albanian letters, there were brave writers, such as; Petro Marko, Mitrush Kuteli, etc., who despite all the political consequences for their lives and those of their family members, did not consider the method of socialist realism, while Lazgush Poradeci, Ali Asllani, etc., broke the pen and did not create again after 1944. We should not leave without mentioning here the valuable help given by the constellation of young Albanian writers, which was formed in the former Yugoslavia.

Our literature from 1944-1991, apart from writers like; Shefqet Musaraj, Aleks Çaçi, Fatmir Gjata, etc., who only wrote works of socialist realism, there were also some writers, such as; Sterio Spasse, Sabri Godo, etc., who created works that belonged to socialist realism, when they dealt with events from the current time of socialism, and purely realistic works when they dealt with Albanian life, or foreign life, of a past time. This group of writers brought both damage and value to our literature, as the case may be. And the literary work of Ismail Kadare and that of Dritëro Agolli, constitute complicated literary phenomena, which require in-depth studies, to find out how far their values and damages have reached.

Albanian realist literature, from the years 1945-1991, differs from the literature of socialist realism, firstly in terms of creative method, because it did not apply its rigid rules, and secondly, in terms of content, because with its ideological content, it did not put itself at the service of evil, but denounced it. Realist literature did not raise the politics of the party and the state into art, but humanity, sound morality, human love, everything that served social progress. It followed the path that Albanian and world literature had followed before 1944, a path that literature continues to follow today, regardless of the currents and literary trends it may be a part of.

The poetic creations of Arshi Pipa (‘Libri i Burgut’, 1959), the portraits of Sami Repishti (‘Pika Loti’, drawn up in the years 1960-1963), the poems of Lek Pervizi and some popular rhapsodes, collected in the volume ‘Albanian Violinist’, created in prisons and internment camps in the years 1944-1991, constitute the foundations, the initiatives of the ‘prison literature’ ’. Of course, these foundations also include other works, which I, as an immigrant, have not been able to add to my hands, since the Albanian governments after 1992 have not shown any interest in the distribution of literary and scientific works, which are published by authors with sacrifices in small editions.

* * *

The volume ‘Pika Loti’ (second edition, ‘PEGI’, 2009, 155 p.) is a collection of lived stories, constructed as literary portraits, which the author wrote after escaping from his homeland in the years 1960-1963, but which he published only in 1997, because he was afraid of causing consequences to his family members and the people he had described in them. The heroes of this work are co-sufferers of the author, in the cells of the investigation, or in the prison of Shkodra and in various labor camps.

The volume opens with the writing dedicated to the mother and closes with the writing ‘Elegy for the brother’, which differs from other writings, because it is not a story or a literary portrait, but a lyric sketch, an elegy in prose.

The author wrote this work in 1970, after the Albanian Security Service spread the false news that the author’s brother, Vehbiu, had died. After the sketch was drawn up, the author learned the truth, his brother was alive. The deep shock and despair caused to the author by the malicious news of the Albanian Security prompted the creation of this extremely emotional and painful lyrical work. Among the various co-sufferers that the author knew during the years of his ordeal, he has chosen some prototypes with which he represented the fate of different layers of the Albanian society from 1946-1956.

The faithful and truthful narration of the lives and sufferings of these heroes through the reproduction of events and conversations that happened concretely in front of the author’s eyes, as well as many different details, creates a very high emotionality and credibility. This emotionality and credibility could not have been created at such a level if these portraits had been treated simply as genuine literary stories. We say this, because in genuine literary stories, the authors, to typify their heroes, use material (events, conversations, thoughts and descriptive details), created by their imagination, and not material taken concretely from life, as it happened.

Typification as a literary phenomenon strengthens the artistic aspect of the work, but weakens the credibility of the events. Since reliability, for the problems and events that are treated in this work, is of particular importance, since it is about concrete events and victims, we say that the creation of these types of stories, interwoven with the patterns of the literary portrait, has been the best path that the author has followed.

The reflection of Albanian life based on the memories of the recent past, selecting events, conversations, thoughts and various essential details, to show the violent deformation of morality and law, the destruction and looting of private property, in the first decades after the Anti-Fascist War, was the path that this author followed in the early 1960s. This path, or a path similar to it, was followed after 1992 by many other convicts, among whom the Franciscan Father Zef Pëllumbi, Visar Zhiti, etc. stood out.

The basic idea of the work ‘Pika Loti’ is the discovery of the fact that communism as an ideology and practice kills the elite, mistreats the average and exalts the inferior. This idea, which the author embodied artistically in this literary work, he also formulated expressly in a political speech, held in 1965, during the rally; “All-American Conference” in Washington D.C., which he quotes in the introductory note of the work (p. 8).

The killing of the Albanian elite (the intelligentsia and the bourgeoisie as a political and economic class), created over generations of ten-year-olds with sacrifices, unfolds through several portraits: Qemali is the portrait, centered on the prominent Shkodran intellectual, Qemal Draçini, the most distinguished lyceum student of Shkodra and of all Albanian students of the University of Florence, where he studied law for two years. The author adored this intellectual for his tendencies, for opening new horizons. This blond and very charming boy, in his early youth, was connected to the communist movement, but when he saw that the ideal for creating a new world was protected by hatred and punishments up to family members and his parents, he left in disgust.

He could not hate and blame his mother for the existence of bourgeois society. With very lively notes, the atmosphere of 1945 is described, when Qemali staged the drama “Beyond the horizon”, the work of the American playwright, Eugene O’Neil, in the theater of Shkodra. This show with its current resonance, about the suffocating state of the intellectual youth threatened by the drought of Marxist dogmatism, shocked the Shkodra youth, as well as the bodies of the new government and the Security. It caused Qemali imprisonment and unbearable inhumane torture, from which he was able to escape by painful suicide by swallowing a large amount of DDT powder, which the prison guard threw into his cell to kill millions of lice.

“One friend and one teacher: two martyrs”, is dedicated to the Vlonia anti-fascist fighters, Hamdi Gjoni and the teacher Bego Gjonzeneli, who were imprisoned, tortured in the interrogator and thrown into labor camps, for the only “sin”, that they did not join the partisan forces, which were created later, but fought as nationalists, against the fascist and Nazi invaders. The deep intelligence of the pedagogue of the Commercial High School of Vlora, Bego Gjonzeneli, is revealed through the reproduction of his conversations with the convicts. The conviction of several communist leaders by the NPSH itself, after the breakdown of relations with J. B. Tito’s Yugoslavia, raised some hopes among the prisoners for the softening of the dictatorship and the improvement of the situation…!

However, the professor cut off the naïve guesses with his own reasoning: “The conflicts are of an incoherent nature of the communist system. We will have others similar to this one. Communists kill each other, in order to face the new conditions without opposition. For absolute dictatorships, the elimination of comrades-in-arms is a fundamental principle. But this should not be understood as a signal of their end…! We have entered a predicament from which it is very difficult to get out. Those who say they control the destiny of our country no longer have this destiny in their hands. Another despot rules today over our country. It’s the Soviet bear.” Similar to the fate of the Vlonjat professor Gjonzeneli, is the fate of the Shkodran professor of philosophy, Preng Kačinari, described in the article “Nji vorr i harruem”.

This professor of philosophy at the ‘At Gjergj Fishta’ high school in Shkodra, a rare intellectual, graduated from the University of Montpellie in France. This professor, with his behavior, intelligence and deep knowledge, had won the respect and love of the students and citizens of Shkodra. After the fascist occupation, he called his students and went up the mountain with them, with whom the author himself fought against the fascist invaders. However, he was despised, left jobless and forced to die of hunger, for the only “guilt” of not joining the communist forces and because he had known the future dictator of Albania closely during his studies, whose jealousy and paranoia did not allow those more capable than him to survive.

During the hero’s last meeting with the author, he formulated in a few lines the essence of morality, the essence of what the state party required from teachers and educators: “Forgive your conscience to the devil, annihilate your personality, lose your dignity as a human being, reject all basic moral principles, then you are suitable for the indoctrination required in education”.

In such a suffocating situation, this pure intellectual, faithful to the principle according to which for nations, as for people, honor stands above life, left unemployed, without livelihood, ended his life by dying of hunger, in the Tirana cemetery in 1956.

Even more tragic is the fate of the Shkodran lawyer, Qazim Dani, who is described in “The old man of number 10”, the man who was imprisoned without the slightest reason. This imprisonment revolted his 16-year-old son, Bardhoshin, who, unable to bear the injustice, decided to escape with two other friends, all three single boys. These inexperienced guys killed the border guards. After they were left to stink in the city square for several days in a row to terrify the Shkodra youth, the police allowed their family members and friends to bury them. Bardhoshi’s mother went crazy from the shock of the macabre event.

When her prematurely aged husband was released, she received him fiercely, shouting: “You killed my son! You killed my son!”, at a time when this father did not know the tragic end of his son. The two, mother and father, left no worse, without bread crumbs, with three daughters who could barely make ends meet, with one of the heaviest jobs, branded with the ugly epithet “enemy of the people”, felt themselves redundant and melted one after the other, waking up frozen from the cold, on the balcony of the house…!

In “Bir i deja i San Françesku” the co-sufferer of torture in the investigation cell, the cleric Father Çiprian Nikaj, is portrayed. This dedicated cleric, together with his colleagues; Father Pal Dodaj, Father Mati Prendushi and Father Bernardin Palaj were arrested in the middle of November 1946, on the occasion of finding in the Assembly of the Franciscans some rusty rifles, which had been left by a German sergeant, during the retreat. Those rifles were neither used nor could they be used, but they had remained in the Assembly due to carelessness, leaving their delivery to the police, today for tomorrow. The spying was done by a young seminarian, recruited by the Security.

The torture of these clerics, who were kept in different cells, was done in order for them to admit that the weapons were hidden to organize the popular uprising against the government, as was said by the Albanian and Yugoslav communist propaganda. In order not to distort the truth, Father Çipriani, confesses to the author, the truth of the presence of those weapons in the Assembly and leaves it as an order; prove this truth after leaving prison. This trust is also the main reason for the drawing of this portrait.

The simplicity of the devoted cleric is given through his repeated prayer to God: Our Father in Heaven! Help me to be grateful for your grace and love!

This modest being, which seemed very shrunken during his prayers, was very powerful in words and thoughts. With the advice and consolation that this fellow sufferer gave to the author before and after the torture, he eased my suffering with the spirit of hope and filled my heart with the spirit of endurance, the author claims, describing the severe psychological condition in the dungeon where the person lost the notion of time and often the desire to live…!

The mistreatment that the dictatorship did to the average people is also given in vivid colors in the writings “Unfortunate Dukagjinasi”, “Djali i Lumė and Bajraktari”. The heroes of these works are sons of the highlands of Northern Albania, honest people, anti-fascist patriots. Such are the Dukagina brothers; Mark and Kolë Prela, the sincere mountaineer Mehmet Lumjani and the bajraktar of a deep village, Sylë Bajraktari. All these heroes, without being at all opponents of power, are punished by it.

Mark and Kolë Prela, loved the new government, but they, as honest people, even though they had fought as anti-fascists alongside the partisan forces, had not agreed to carry out the murderous orders of the People’s Protection Brigade (Security forces), who went through the Highlands, to massacre the inhabitants there, with the sole purpose of instilling terror, fear and absolute submission to the new “popular” government.

The simple and honest boy, honest Mehmet from Luma, could not understand how the man could stoop so low as to slander his fellow villager. The security of the village had slandered as; Mehmeti did not like power, as if he was an “enemy of the people”, which caused him to be imprisoned and sentenced to forced labor in the mud of the Maliq swamp. His rhetorical question: “How can a man stoop so low”!?, used as a refrain throughout the writing, reveals the injustice of many punishments and the downfall, not of a few spies, but of the communist government itself. This power that came to power with a bang, as the creator of the new world and the new man, soon revealed its true anti-human dictatorial face.

To justify its violence and to create the idea that the ‘old world’ it overthrew was a reactionary world, this power through various punishments declared many words, as well as their bearers, to be hostile, reactionary and anti-popular. With rape, the words; ballista, bayraktar, gendarme, defense lawyer, priest, etc. were charged with a negative emotional content and all ballistas, bayraktar, gendarmes, defense lawyers, priests, etc. were declared and fought as enemies and traitors. Among these persecuted are many of the convicts we mentioned above, as well as Sylë Bajraktari, the man who could not understand why he was called “enemy of the people”, “bloodthirsty of the people”, when he and his predecessors as Bayraktar had tried to apply the Canon and the laws of the Mountains to maintain order in his village.

The personal life full of hardships and the close knowledge of the sufferings and the tragic end of the lives of these representatives of the Albanian intellectual elite, pushed the author to arrive in the years 1959-1962, in a very mature characterization of the era of the dictatorship since then, a characterization in which our writers and researchers of our days have not yet reached.

For the author, that era was the era that killed the honest teacher, that disappeared the devout clergy that imprisoned the intellectuals formed in Europe that tortured the merchant, that tortured the worker with hunger and that impoverished the peasant until he could no longer go. Age which desecrated the student, poisoned the youth, exalted the idiot, inspired the credulous. She made a cult of hatred and an ideal career.

Suffering together and getting to know the life and death of such heroes, gave the author the impetus to find the way of salvation, not in enduring suffering, which would soon lead him to an untimely death, during a new imprisonment, new exile, or labor camp, but in escaping from the homeland. The author’s life, up to his escape, is covered in detail in the autobiographical volume ‘In the Shadow of Rozafa’ (‘Onufri’, 2004, 344 p.), where the focus is not on the deeds and conversations of fellow sufferers, but the life, suffering, thoughts, meditations and generalizations of the author and his family members.

In the meantime, we emphasize that the rise to high positions of inferior people, who served with blind loyalty without any remorse to the power in power, is given by showing how ignorant, almost illiterate people, taken from the villages, were armed and put in commanding positions in prisons and labor camps, where they cruelly mistreated innocent convicts. To these heartless people, the author does not dedicate any portrait or full text, but only describes them clearly and in contrast with his fellow sufferers, people condemned without guilt.

The author makes an exception, only for Xvehiri, as the prisoners called corporal Jonuzi from Berat, whom he portrays in the portrait ‘Bayraktari’. This person was different from the other policemen, he had woken up from the indignities of the state party and tried to ease the suffering of the convicts as much as he could, sometimes by telling them who the recruits were among the convicts, sometimes by telling them news from life outside the prison…!

Finally, we cannot leave without emphasizing that in all the writings summarized in the book ‘Pika loti’ there is a common artistic characteristic. In them, the use of a very sensitive lyricism is noticeable, the description is very faithful and with well-chosen details to characterize the heroes that are portrayed. The author’s lyrical interventions, expressions of emotions, meditations and precise formulations for the characterization of the era, increase the emotionality, reliability and authenticity of the writings and especially the artistic level.

This work, as well as his other works, stand out for the rich and elaborate language, for the Shkodran literary dialect, very close to the common Albanian literary language. This phenomenon is rare among those who write in the Shkodran dialect, because most of them, wanting to show the richness of this dialect, emphasize the differences from the literary language and use many of its sub-dialectalisms.

In conclusion we say that; the work “Pika loti” is a worthy part of the foundations of Albanian prison literature, because it precedes the major work “Rrno only per me tregue” by Father Zef Pëllumbi and the novels of Visar Zhiti, while the autobiographical work “In the shadow of Rozafë” is a sister of them. Memorie.al