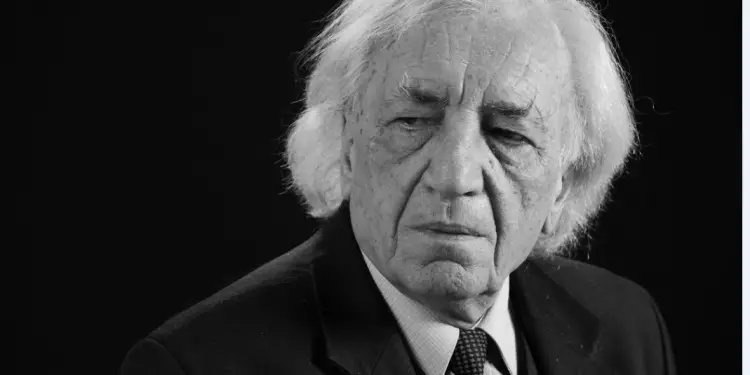

Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes a rare story of the renowned writer, Dritëro Agolli, regarded as the “Patriarch of Albanian Letters”, who in 1956 when he was a young journalist in “Voice of the People”, went into service in the district of Puka and stayed in Fushë-Arrëz with his friend, the young doctor, Alfred Serreqi, and with him traveled to the village of Kryezi, where Mark Dode Alia’s large and patriarchal family lived. Agolli’s rare testimony about this visit to a well-known peasant house, where one of the boys of this house had made a small hydroelectric power station that illuminated all the rooms, which tore Dritero since he came to Tirana, wrote and published in “Voice of the People” a report entitled “In Search of a Dream and a Dynamo”, a writing that would bring much trouble and anxiety later on.How they called Agolli to the Central Committee where they were heavily criticized, accusing him of being part of his report, Doctor Serreqi, who had all the people in his family in prisons, internment, or even executed as “enemies of people, ”and the night they had been at Mark Dode Alia’s house, a floor upstairs had diversers. The 90-year-old man was sentenced to 10 years in prison and Agolli was censured for the book where Serreqi’s name was published…!

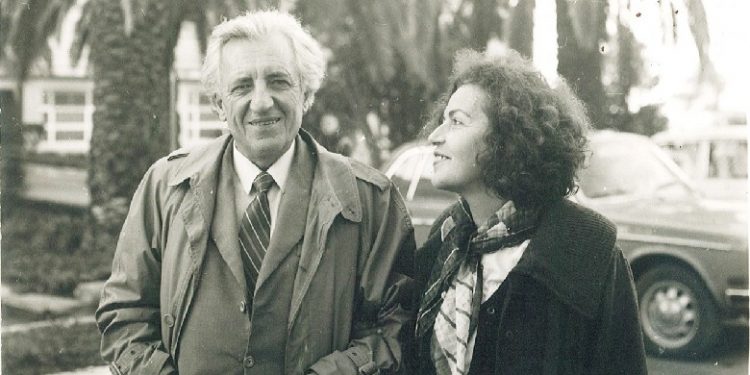

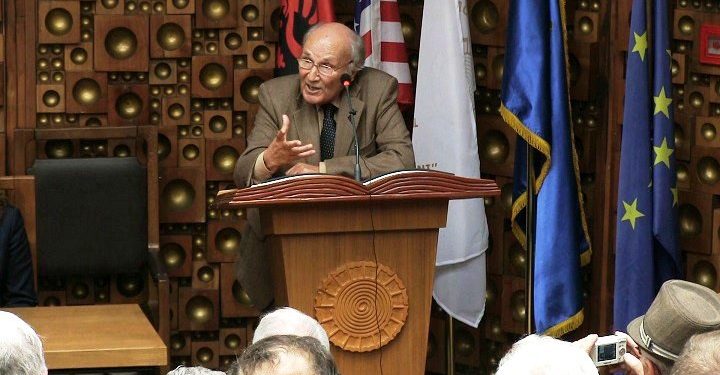

Among the many friends and friends he had throughout the country where he often traveled as a journalist was a young doctor from Shkodra, who served in the small hospital of miners and sawmills in Fushë-Arrëz district. of Puka. Although the young doctor was the sucker of a well-known Catholic family in past regimes, where most of his relatives, starting with his father, (former Zog minister) were serving long sentences in political prisons, or were fired as “enemies of the people” that with the coming of the Communists to power in December 1944, “Voice of the People” journalist Dritero Agolli did not want to know about them. He did not miss a chance to meet his friend in the distant mountains, who in 1965 also made a character in one of the newspaper reports. But that would cost him little trouble. Even being the subject of an in-depth analysis in the press section of the Central Committee of the APL, where he tried to defend himself by saying that he knew him as the grandson of renowned doctor Frederick Shiroka, he did not escape without a “shower” cold”! Who was the new doctor, the friendship with which brought Dritoit into trouble and in what circumstances did he make that character of his writing published in the Voice of the People? About this and many other events unfamiliar with his life, we know from an interview that the famous writer and poet Dritero Agolli gave us 20 years ago, which Memorie.al is exclusively reprinting this writing on the anniversary third of his separation from life.

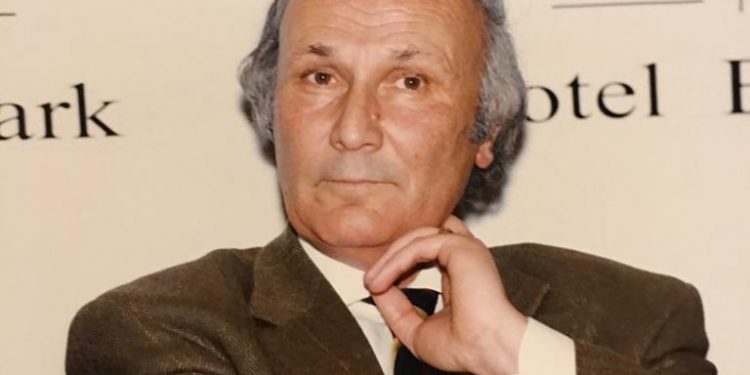

Mr. Agolli In what ways were you first introduced to Alfred Serreqi, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1992-1996?

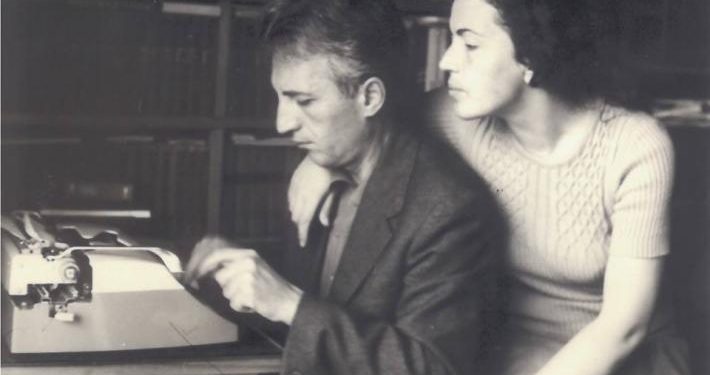

I was first introduced to Alfred Serreqi in the early 1960s when I was a journalist at “Voice of the People” and he was a doctor in Fush-Arrëz in the Puka district. We had some acquaintance before in Tirana, but we formed a close friendship when he was serving in the small town of miners and sawmills where I often went with services to report.

But besides Serreqi, you had other friends in Fushë-Arrëz?

At that time, my close friend, Vito Koci, also worked as the chief engineer of the Sharres, who later became one of the well-known journalists and publicists of the Albanian press. Vito was also Serreq’s close friend so we bonded more closely with each other. Every time I went to Fushë-Arrëz, I came to Alfred’s small room, a man who was very passionate about books, science and art.

How does Mr. Serreqi at that time and the place where he lived and worked in Fushë-Arrëz?

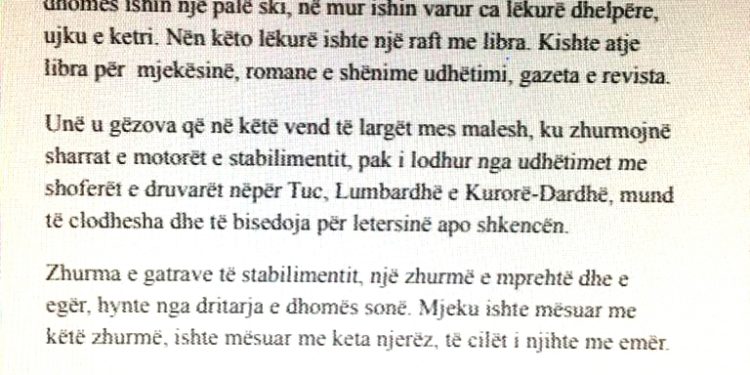

I remember now the ambiance of that room with a pair of skis on one of its corners, and some animal skin hung on its walls, for Alfred was passionate about hunting.

Did you say that Alfred was very fond of books …?

Yes, underneath those skins was a large library of books on medicine in some foreign languages, novels, newspapers, and magazines. To tell you the truth, when I first went into that room, I was overjoyed, as in that little place between the mountains where the sawmill engines were jamming, I would have the chance to relax on the long road with my drivers. the woodcutters of Tucci, Lumbardhe and Crown-Dardha, and would talk about literature or science with that young doctor who was behind the books. These were only one side of the “Serreqi” medal, as that young doctor enjoyed special respect throughout the Fushë-Arrëz area. He spent most of his time between the inhabitants of those areas making visits and being close at every moment to all the health problems they had. Alfred did not hesitate to travel for hours, day or night, in the snow and frost wherever he was required to go to the sick. It was for this reason that he had won the hearts of the inhabitants of those areas who could not be removed.

Did you know the biography of Serreqi, where many of his relatives and family, starting with his father, served sentences in political prisons as “enemies of the people” or his uncle was shot dead in 1946 etc?

I knew very well the biography of Alfredi and the Serreqi family, but I had no problem associating with him, as he was the nephew of Doctor Frederick Shiroka, one of the most renowned doctors in Albania at the time. Given this fact, I was somewhat protected if I were raised as a problem, but what made me more liberated from socializing with him was the fact that everyone in Puka spoke well of Alfred. It is no exaggeration to say that they were talking about him as a hero.

Were these considerations prompting you to publish the report on the new doctor Serreqi, or something else?

The report I wrote then in “Voice of the People” I did not praise Serreqi for having a friend, but for a family living in the village of Kryezi in Puka. But since it was Alfred who suggested and pushed me to do that reportage, I mentioned it in writing, as he accompanied me to that house. So Alfred was a natural part of that reportage I did at the time.

Who was that family?

It was the home of Mark Doda Alia from the village of Kryezi in Puka, which was a large patriarchal family of about 60 members, which was no match in any other province of Northern Albania. But what moved me the most to write that story about Mark Dodd’s family, after Alfred’s suggestion, was not the number of its members, but something else quite special.

Specifically, what?

At that time, in those remote villages between the snow-covered mountains, electrification had not yet taken place, and one of the nephews of the head of that large family, called Dede, had made one as a small hydroelectric power plant supplying electricity. all the rooms of that great house. That was the reason that led me to go to that house with my own eyes to see the miracle that the farmer, who worked as an accountant at the Sawmill Plant, did. And as I said above, I was there with Serreqi, who was a close friend of that house.

How do you remember the visit you made to that house and when it happened?

It must have been the beginning of March 1965 when this event happened. At that time I had gone to Fush-Arrëz and as usual I was in Alfred’s room talking about a book by a German archaeologist, which he had just found. While we were looking at the notes of the German archaeologist, the door rang and a fat man entered the room and Alfred introduced me as a nurse. He said, “Deda is waiting for us.” I asked if there were any patients, but Alfred told me that a friend of his who had left the hospital the day before had invited them home. He also told me that the person waiting for them at home was a very nice person, and he invited me to go with them.

Did you go immediately, or did you hesitate?

I decided to go after Alfred prompted me with some words that touched my professional journalist seat, and so we set off. We walked for a few hours every three hours across the side of a mountain, and as we approached the Leyzza River, Alfred showed me the lights of the house where his friends lived, which was known throughout the province for its generosity, or as a baker’s house, say it differently on those sides. I was amazed at how it was possible to have electric light in that place, and Alfred told me that there was a small hydropower plant nearby that was built specifically to light that house. When we got there, according to the custom of those places, Alfred called out, “Do you want friends, lord of the house.” The owner of the house called Mark Dode Alia went out into the yard and invited us inside that big house like a sari, leading us first. The room we sat in was as big as a crop house, and all the members of that family came to meet us.

How do you remember the reception they received there?

We were served snacks and brandy and the conversation continued almost all night. They lived very well and that house lacked nothing. The Doda Alia brand told us that things in that big house were separate and everything worked wonders. One was responsible for the affairs of the agricultural economy, one for the domestic economy, the other for financial expenses, one for the children, and for all the problems the house had.

What about the hydropower plant that you went to…?

One of Mark’s nephews, Deda, also told us the whole story of how he had set up and implemented the equipment (Dinamo), with which he had built the small hydroelectric power plant that supplied their large home. While he was speaking I kept notes in my block, as soon as I returned to Tirana, I would write the report for which I had made my way to those distant mountains. So I did, when I returned to Tirana I wrote a report titled “In Search of a Dream and a Dynamo”. In that article which appeared in the newspaper Voice of the People dated April 18, 1965, I have described the whole visit to the home of Marka Dode Alia, as I tell you in this interview, since my acquaintance with Alfred Serreqi.

How was the reportage received by your superiors?

The report was very well received in the newsroom and for that writing I received occasional congratulations from colleagues and newspaper executives.

But from the information I received before coming to this interview with you, you have also summarized this report in a book of your own that was published a few years later, but there are some changes. For example, the reportage characters there are only with names and not with surnames as in the original script in “Voice of the People”. Why did this happen, did you notice that you had written in superlatives for the doctor Alfred Serreqi, who was known as a man with a bad biography?

No it is not exactly so. To begin with, I wanted to tell you that the book about journalism that includes the reportage we are talking about was not made by me. That book was published by the Naim Frasheri Publishing House, which also selected my own writings, which I was not even asked about at the time. As for the surnames of characters not put there, it has nothing to do with Serreq.

Why…?

At the time, then, in the publicist books of the 1990s, it was a rule that strangers were not given surnames but names. This was done deliberately, as any of them could later be politically punished and therefore the book had to be removed from circulation. Names and surnames were allowed to publish only known characters, such as Haxhi Lleshi, Myslym Peza, etc., who had guarantees or, as it were, could not be punished.

You were criticized for Alfred Serreqi for characterizing your reportage?

Alfred Serreqi was even heavily criticized, but not in the newsroom.

But where….?

Some time after that report, I was called to the APL Central Committee apparatus, and in the press I ate some good wood because I had praised that talented young doctor but with a bad biography. Not wood, but they make me comfortable. ”

Agolli’s testimony: How did I defend myself in the Central Committee for Serreqi?

While in the editorial of the Voice of the People newspaper for a report titled “In search of a dream and a dynamo”, the young journalist Dritero Agolli received many congratulations from his colleagues and superiors, the situation changed a few days later when he called in the Press section of the Central Committee of the ASP. Related to this, the renowned writer and poet Dritëro Agolli recalled: “That day when I was called to a press conference at the APL Central Committee, I had thought of everything, but they would criticize me and would to give me some good wood for that reportage, I didn’t even bring it to mind. This was due to the fact that the report was well received after the publication and I was congratulated not only by my colleagues and friends, but also by the superiors in the editorial staff of Voice of the People. At that Press Session I was asked to give an account, telling me why I had so highly praised Dr. Alfred Serreqi, at a time when he was a man from a family with a bad biography, with his father and relatives of the family in political prisons, with a shot uncle and a fugitive who had fought against popular power. So in short I was criticized there for mitigating class warfare, and worse, for having written well for a man who had a stark biography. After the criticism I received, I told them that the new doctor Alfred Serreqi, I knew him as the nephew of Doctor Frederick Shiroka, and had written nothing more than what people in the Puka district were talking about. I ended my speech by saying: For Doctor Alfred Serreqi in Puka to talk like a hero. But not even these words saved me from the many criticisms and remarks that were made to me”.

Agolli’s Testimony: A Security Officer told me that Serreqi and I had slept in that house with divers and Marka Doda Alia served 10 years in prison.

On the night of March 1965, while traveling with the young doctor Alfred Serreqi to the village of Kryezi in Puka, the “Voice of the People” journalist, Dritëro Agolli, had never thought that the house they would spend the night in was even some diversants. Concerning this, the well-known writer told us: “In the morning when I went out into the backyard to wash my eyes, I heard some movements of leaves and shrubs. Behind some thick trees there were three to four deleted people who said to each other: ‘No this is not him, this is a journalist in People’s Voice, I know. I didn’t pay much attention to those words and took them for curious people, but it wasn’t. About three months later, somewhere near our newsroom, I was met by a State Security officer with the surname Xhufka, who worked years later at Radio Tirana. He was kind to me and told me that the night I had slept with Alfred at Mark Dode Alia’s house, the upstairs had been sheltered and there were some divers coming from overseas. And that was why the entire house was surrounded by State Security forces, but since we were inside, they did not intervene at night as they did not want to cause harm to innocent people. So the security officer told me about that night. But he did not tell me if the divers had left when we arrived at that house, or at night. Later, the editorial staff of “Voice of the People” was also informed on the official channels and my superiors and colleagues often mentioned it with laughter. Shortly afterwards, one of the members of that house was arrested and held for some time in prison, but later released after being told that the divers had entered the house by force. But that did not end there, as a few years later the head of that large family, Mark Dode Alia, though in his old age, was arrested on charges of sheltering diversors and serving 10 years in the prisons of the communist regime. Mark was released from prison when he was in his 90s, and he has died if not mistaken since the early 1970s. All this was shown to me by one of the nephews of that family, who came and met me at my home in Tirana a few years ago. ” Memorie.al