By Nikol Loka

Second part

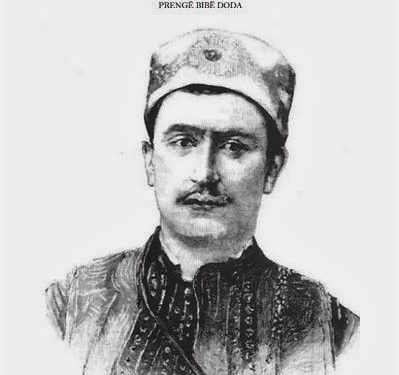

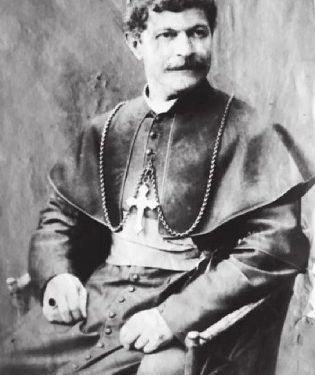

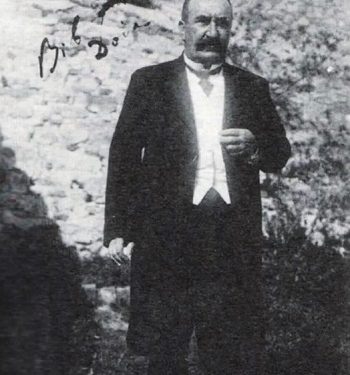

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the field of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the shrine of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. Studying such an important and complex figure, such as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Loka has adhered to the end of space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have unfolded.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

Continues from last issue

The genealogy does not lead us to the founder of what was once called the Chief of Mirdita. The name of its own father is not known nor of the founders of the three brotherhoods (Orosh, Spaç and Kuzh nen) and it is the only tribe that does not show generations. 6 There are legends that connect Mirdita with an old tribe that continues to be called Morinë in Kosovo, which lived in the territory of Pashtriku of Has, where the village with the same name is still located today and, from there, it has spread to several the territory of Kosovo. In the book “The truth about Albania and the Albanians”, Pashko Vasa writes that; “Mirditors are descended from Pashtriku”7. Pashko Vasa remembered that he had seen a document of Biba Doda, written by the Kadi of Zadrima, in the 15th century, where it was noted that Llesh Gega, Dodë Gega and Tanush Gega and another, had left the mountains of Pashtrik and settled in Mirdita 8.

Indeed, even after so many years, a connection between the Pashtrika Hasyans and the Mirditors is discernible. Thus, the new churches erected in Orosh, Spaç and Kuzhne in the 16th and 17th centuries have the same names of saints as the old churches in Has of Gjakova: Saint John, Saint Nicholas, Saint George, Sëlbuemi, and so on. Perhaps the new population that came from there brought the holidays with them and celebrated them…. It is interesting that in some Christian villages, but also Muslims in Has of Gjakova, the feast of Saint Nicholas is celebrated, just as it is done in Orosh, Kuzhnen, Fane, etc. 9

Yes, in the area of Pashtrik, there are villages close to each other that belong to the same brotherhood, named Bardhaj and Letaj, as two brotherhoods of Blinishti and Mirdita are also named, which shows that; they came from the same place. As a historical document that proves the arrival of the population from Pashtrik, is the ‘ilami’ (court decision), which was issued in 1443 by the Kadi of Zadrima, on the occasion of the settlement in Ndrefana of some families who moved from the village of Pashtraq i Gjakova 10.

With various sources and comparative deductions, the arrival of a considerable amount of population from Kosovo is confirmed and, as a point of memory, Pashtriku is noted. The conditions of arrival are explained by the circumstances of insecurity, by the threat of the Ottoman invasion, but of course these threats must be earlier, from the time of the Slavic invasions in the XIII-XV centuries 11.

These data are sufficient, meanwhile there are other data that connect the territory of Pashtriku with Oroš and with Spači 12. Thus, elders of the beginning of the twentieth century, showed with great conviction that; the ancestors of the family of Prengë Bibë Doda of Oroshi, had their properties in Pashtrik and Rrafsh i Has, inherited since they came from there and received rent for grazing, in the mountains of Pashtrik and in their lands in Has i Rrafsh , rent that was terminated in time. They also said that even at the beginning of this century, from the Gjomarkaj family, they went back and forth with the Maroshi family on the side of Gjakova, being known as each other’s family. “In Pashtrik, Gjomarkaj have their own tribe called Marosh, it’s a rich family, all Mohammedans. The members of that tribe, they have recently in the Gjomarkaj’s island in Orosh, who ambushed them and shot them as fellow tribesmen, the Gjomarkaj also stayed for three days in the Marosh’s island. , in 1921. 13

Oral traditions preserve Oroshi as the first place where the Mirditas settled. According to Kolë Shtjefni, who has carefully collected the oral tradition of the origin of the inhabitants of Mirdita, since the fifties of the last century, “the three brothers came from Gjakove, here in Orosh, where they have a forest. After some time, they are separated. One remained in Orosh, the other in Spaç, the other in Kuzhne. These three bajraks do not even take naps with their husbands, because they know the place for their brother”.14

Only these three Bajraks, who were once the Mirdites, who must be believed to be the Mirdites, have preserved this brotherhood for hundreds of years until our days, without breaking it. They have never married among themselves, they have the same customs, clothes and everything else, and they keep themselves as brothers just in case. They show that; Bibë Dodë Pasha, the prince of Mirdita, wanted to break this brotherhood, he married a very beautiful girl, Quejtun Bale, the daughter of Marka Pjetër Vorfi, from Dom t Spaçi village, but he needed the consent of three Bajraks .

For this purpose, men and women gathered at the Shpali oak assembly in Blinisht, and there Bibë Dodë Pasha revealed the purpose of the meeting and asked for consent to this marriage, to break the centuries-old brotherhood. The meeting was covered in silence and everyone had thought that such a proposal, which was made by their leader, did not seem fair to them, it would destroy the brotherhood…! At this time, a woman with a child on her back, the daughter of the Permargetajs in Spaç and married to the bajrak of Dibrri, who was going to Pasha, to her parents, passed by.

Passing by, he greeted the assembly with these words: “The stupid assembly took my brother.” The meeting answered: “Greetings sister”! This woman’s word; “my brothers, it shocked them a lot, even the members of the assembly, even Biba Doda herself, therefore the assembly, completely of one opinion, said: “Then it remained without spoiling even today and back, our brotherhood, as you have always had and the assembly was dispersed. Bibë Pasha, gave up that idea and then later, he didn’t even think about discussing the destruction of the brotherhood”. 15

As the residence of the Mirditas, tradition gives Kolike Kodër or Mashtërkorë Hill, as they call it today, where in the beginning “there was a place for the Mirditas, in the middle of a dense forest of hornbeam and pines.” Luli and Skana spears were found there. Luli’s origin is unknown, while Skana is said to be from Kruje. 16

In historical documents

What do the historical data provide? In what is called Mirdita, in the broadest sense, in the Middle Ages, there was an old local arboreal population, and this is proven by the numerous cemeteries, such as joint burials in one place, developed fruit culture with vineyards and trees, flour mills, which speaks of a sedentary population. Another important evidence is the presence of numerous churches and several monasteries, which have their roots in the early Middle Ages and the body in the Middle Ages. 17

In the village of Mirdita, of eleven houses, in 1529, the growth of that tribe can be seen. In 1671, Mirdita consisted of ninety-seven houses, with eight hundred and twenty-five inhabitants and included the settlements: Orosh, Lagje, Mashtërkorë and Tumerish. In the first historical records, there is also a Venetian document, at the end of 1500, published in “Starine te Zagrebit”, which states: “In the mountains of Lezha, there are villages called Mirditas, populated by Catholics, with 12 thousand men under arms, ready for command”. 18

For the first time on the maps, Koroneli places Mirdita under the name “Merediti” and defines the upper valley of Fandi e Vogël as its location. 19 From there, Mirdita has started the process of expansion. Franc Nopça writes…”The history of Mirdita runs throughout, the tendency to assimilate border lands. In the north, long ago its border did not even reach Kalivare. Today, Gojani and the territories north of Kalivara belong to Mirdita, and even the Arsti Field and the Mountain Pass are in the sphere of Mirdita’s interests. It was also able to extend from the side of Lura, conquering Guri e Kuq. 20

This influence of assimilation goes so far, that Mirdita could close the Prizren – Shkodër road at any moment, sometimes in Qafa e Mali and sometimes in Kçira, which once did not even belong to Mirdita. The small village of Mirditas, Troz, north of Duš, is one of the most advanced outposts in the depths of the northwest. 21

According to Prend Doç, the Mirdita of the twelve Bajraks, as an autonomous province, in the middle of the 19th century, stretched over a territory of about 800 km. and there were 83 villages, 2,400 houses and about 25 thousand inhabitants. The union of the twelve bajraks of Mirdita was not a violent mechanical union. It was based on that common concept, which naturally originated from the heritage and the land, in which the old material and spiritual ties lived intact, between the culture, faith and land of the ancestors, which essentially for the Mirditors, were and remained inalienable. 22

SELF

With the Ottoman conquest, the local feudal class was destroyed in the Highlands, while the structure of the old social organization withstood all the difficult tests of the time. The leaders remained in the leadership of the resistance of the free mountain peasantry. They led the insurgent movement, signed on behalf of the provinces or represented them, in various assemblies. Fran Bardhi, in the relation given for the province of Puka, in 1637, speaks extensively about the local chiefs, who were called kefalinj.

From the outside, they showed their social position by wearing a silver axe, the size of an average apple, in the buttonhole of their shirt, while the most powerful and the richest had two to three such axe. . These headscarves, when they went to assemblies, parties and fairs, they tied their heads with a silk cloth, to distinguish themselves from others. According to a letter written in the Albanian language, in Gash of the Highlands of Gjakova, on May 30, 1609, we learn that; “they were the leaders who were also interested in the religious issues of the population”. 23

But there was also a difference between them, as they were divided into simple heads, small ones (capi apo vechi) and chief ones (principali capi). “Noi capi et principali, di tutto il popolo d’Albania”. 24

The persistent stand of Mirdita and its neighboring provinces, against Ottoman violence, forced the Turks to change their policy towards these provinces. In the second half of the 17th century, the Turks entered into talks with the chiefs of the highlands to reach an agreement with them, in an attempt to get the assemblies of the highlanders into their hands, as a form of their penetration, into the rebellious highlands.

With the creation of the bajrak, some new administrative elements and some changes in the eldership procedure were created, rather as a replacement of those that regulated feudal relations, before the Ottoman occupation. Mirdita, for a long time, was hanged by Sanxhak of Dukagjin, based in Peja. With the arrival of the Bushatllinj, it was included in the Paschalek of Shkodra, but most of the time, it did not include all twelve bajraks. Although the provincial unity was formed and for the most important issues, the Assembly of the Twelve Bajraks functioned, the Ottoman invaders kept the province almost constantly fragmented, administratively, in order to weaken the Mirdita factor, which had become threatening.

The formation of Mirdita is directly related to the role of the Gjomarkaj family. From the house of Gjomark and Prijs Markolaj, came rulers with the right of inheritance. The vizier of Shkodra, Mustafa Pashë Bushati, on November 25, 1815, addressed the elders, the chieftains of Mirdita with a proclamation: “I inform you that; John Mark’s house has always been known and valued first, throughout Mirdita, so it is and will be in the future, and I warn you to know all of you who have been mentioned here. This is how it was known by my ancestors, the Viziers of our Divan”. 25

The Mirditas maintained their alliance with the Bushatlli. Mehmet Pashë the Elder, who himself was held in Mirdita, in 1756, asked for their help and in the Assembly of Podgorica, the Mirdita forces were a living factor in support of the Bushatas. Other Ottoman officials have also made official recognition of the Gjomarkaj’s primacy over the Mirdites. In 1837, a letter from the Divan of the Royal Army and a letter from Ismet Pasha, ruler of Dugagjin, affirming Mirdita’s privileges and recognizing Biba Doda as Kapidan, were sent to the Bajraks of Mirdita. 26

Likewise, in 1840, Valiu of Rumelia informed the sanjaks of Prizren, Dukagjin, Elbasan and Shkodra of the recognition of Biba Doda. 27

Regardless of the formal recognition, the Ottoman authorities, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, have tried to interfere in the self-government of Mirdita, duplicating the traditional leaders’ canonical functions with state offices. Thus, the Captain was also called Kajmekam and was paid a salary by the state. Meanwhile, in 1865, the Ottoman authorities officially made Mirdita kajmekamlek and Kapidani was paid a monthly salary of 600 groshis.

He had the people he governed with, who were popularly known as the big chiefs, one for each bajrak, who made up the Administrative Council of Kaza. The great leaders of Mirdita, according to the Bajraks, were: in Orosh, Marpepajt; in Spaç, Përmargjajt, in Kushnen, Baca, in Fane, Dodëgegajt, in Dibërr, Paluca. The captain also had a secretary in his administration, who was paid by the state. The Kazakh secretary (qatipi) kept correspondence in the Ottoman language.

According to the original documents, found in AQSH, it appears that the secretaries of Bib Doda were Pashko Vasa; John Melgushi; Loro Gurakuqi. In 1895, Marka Gjon’s secretary had been a hoxha. 28

Under the orders of the Capitan, there were also twenty boys. Ami Bue, writes that; captain Preng Nikolla (must be Bibë Doda, N.L.) paid boys, with whom he carried his orders to the country. They performed the duties of gendarmes, were locals and wore national clothes. They were responsible for maintaining order and escorting the captain. These gendarmes remained under the command of Biba Doda, but were no longer accepted in Mirdi after his death. Only with the occupation of Mirdita, in 1877, was a battalion of sappers sent to Orosh, with Commander Dodë Gegë, at first with the rank of Captain and then that of Major. Memorie.al

- Kahreman Ulqini, Structure of traditional Albanian society, “Idromeno” publications, Shkodër 2003, p.52-53

- Pashko Vasa, “The truth about Albania and the Albanians”, publishing house: Argeta – LMG, Tirana 2010

- Vassa Efendi, the truth about Albania and the Albanians, translated by Mehdi Frashëri, Tirana 1935, p.87

- Mark Tirta, Old Mirdita and migrations of its population, Mirdita, Tirana 2002, p.18-19

- AQSH, P.130, file 368

- Mark Tirta, Old Mirdita and migrations of its population, see Mirdita in history, p. 15-16

- Mark Tirta, Old Mirdita and migrations of its population, Mirdita in history, p.18-19

- Zef Mark Harapi, Mirdita in oral history until 1929, Hylli i Drita, Year VII, No.1, Shkodër 1931, p.41

- AQSH, P.586, D.41, year 1928, p.9615. Kolë Shtjefni, Ethnic Mirdita, … p, 13-1416. Kolë Shtjefni, Ethnic Mirdita … p, 59-63

- Kolë Shtjefni, Ethnic Mirdita, … p, 13-14

- Kolë Shtjefni, Ethnic Mirdita … p, 59-63

- Mark Tirta, Mirdita e mochme e migrime… p.15

- Luigj Martini, Bibë Doda (1820-1868), publications “Geer”, Tirana 2012, p. 2

- Ermano Armao “Places, churches, rivers, mountains and different toponyms on an ancient map of northern Albania” Korbi, Tirana, 2006. p. 22

- Baron Franz Nopcha, “Das catholische nordalbanien” Vienna, 1908, p. .254 56

- Frank Nopça, Highland Tribes of Northern Albania and their customary law, translated by Dr. I swear. Mihallaq Zallari, “Eneas” publishing house, Tirana, 2013, p. 242

- Luigj Martini, Bibë Doda… p. 57

- “Zeischrift fur balkanologle” (Wiesbaden), Helt 1, 1967.

- L. Ugolini, Pagine di storia veneta, “Albanesi Study”; III-IV, 1933-1934, p. 21-23

- AQSH, P.79, file 21, p.13

- AQSH, Fund 10, file 1, p.1; file 2, p. 1-3

- AQSH, Fund 121, file 73, p.6

- Teodor Ippen, Travels in Albania (1897-1903), p.12 (AIH)

The next issue follows